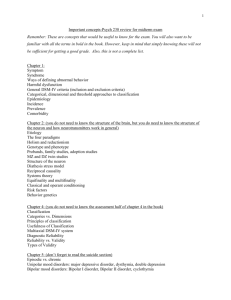

PowerPoint - Lakeview Health

advertisement

Welcome Rogers treats children, adolescents and adults with: • OCD and anxiety disorders • Depression and mood disorders • Eating disorders • Posttraumatic Stress Disorder • Addiction 800-767-4411 rogersbh.org Anxiety and Addiction Michael M. Miller, MD, FASAM, FAPA Lakeview Professional Lecture Series Lakeview Health Jacksonville, Florida November 20, 2015 Michael M. Miller, MD, FASAM, FAPA mmiller@rogershospital.org Medical Director Herrington Recovery Center Rogers Memorial Hospital Oconomowoc, Wisconsin Clinical Adjunct Professor University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Assistant Clinical Professor Medical College of Wisconsin, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health Past President American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) Director American Board of Addiction Medicine (ABAM) and The ABAM Foundation Fellow ASAM and American Psychiatric Assoc. Member Council on Medical Quality and Population Health, Wisconsin Medical Society Member Council on Science and Public Health, American Medical Association Disclosures Alkermes a pharmaceutical firm Honoraria: participation in training to be member of speaker’s bureau, and for speaker’s bureau presentations Braeburn Pharmaceuticals a pharmaceutical firm Stipend: participation in physician advisory board BioDelivery Sciences International (BDSI) a pharmaceutical firm Stipend: participation in physician advisory board Honoraria: participation in training to be member of speaker’s bureau, and for speaker’s bureau presentations Curry Rockefeller Group a marketing consulting firm Consulting: advising on content of patient education materials for newly marketed pharmaceutical; advising on content of postmarketing survey of patients receiving a pharmaceutical; preparation of presentations for national medical education conferences American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry - 1987 • First ABPN CAQ Exam • 1994 The Addiction Specialist Physician • Addiction Medicine – All specialties – 2500 Diplomates • Addiction Psychiatry – Board certified general psychiatrists – 1000 subspecialty Diplomates www.theabpm.org The newest multispecialty subspecialty certification program in the American Board of Medical Specialties Anxiety and Addiction Basic Premises • Addiction is Common • Anxiety is Common • Many people with Anxiety use Substances • Many people with Anxiety have Addiction • Many people with Addiction have Anxiety • Many people with Addiction have Anxiety Disorders, Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders, and Traumatic and Related Disorders The Broader Context: “Dual Diagnosis” -- Basic Premises • Addiction is Common • Mental Disorders are Common • Many people with Mental Disorders have Addiction • Many people with Mental Disorders have Unhealthy Substance Use • Many people with Addiction have • Psychiatric Disorders • Many people with Addiction have • Psychiatric Symptoms Dual Diagnosis MI + CD MI + unhealthy substance use CD + psychiatric symptoms Clinical Management is the Challenge Dual Diagnosis • This issue is one of science: what are the conditions and how often do they co-occur? • The issue is more one of clinical practice: – How best do we meet the needs of patients? • It’s also an issue of Health Care Financing and Service Delivery: – How do you design systems to meet clinical need, and what are the funding streams and how do they impact what is possible to do clinically? The Clinical Challenge • This patient has a problem that I don’t really know how to address; what do I do? – I am a chemical dependency counselor without psychiatric training; something is amiss, I’m not sure what it is, and I feel overwhelmed to respond – I am a mental health clinician without addiction training; I know this person is “using” but I’m not sure what and I’m not sure what I can do for the patient if he/she is using; I feel overwhelmed The Clinical Challenge • Even worse: I don’t see what I don’t know • The patient has a co-occurring condition, and from my perspective/experience/training, I don’t recognize it and so I don’t address it, so it is missed, and clinical outcomes suffer accordingly • “System results” suffer, health care costs are greater than necessary, relapse leads to re-admissions (which in “old” systems of healthcare finance and delivery, were “good” for providers!) Dual Diagnosis: Why is Clinical Management a Challenge? The training of clinicians differs: MI + CD The clinical orientation of clinicians differs. Service Delivery Systems are separate. Health Care Financing Systems are separate. Dual Diagnosis • In order to understand “dual” diagnosis, a clinician should understand addiction AND mental disorders (know “both parts”) • In order to be able to effectively treat “dual diagnosis” cases, a clinician should understand addiction treatment approaches (psychosocial treatments and pharmacotherapies) and psychiatric treatment approaches (psychotherapies and medication management) Dual Diagnosis Editorial comment (based on 3+ decades of experience): • Among physicians, fewer psychiatrists understand addiction or addiction treatment, compared to addiction medicine physicians who understand psychiatric conditions and treatments. • Psychiatrists may have had little training in addiction or exposure to recovery. Dual Diagnosis Editorial comment (based on 3+ decades of experience): • Addiction medicine physicians have had some training in medical school in psychiatry, and they see many cases of psychiatric co-morbidity and acquire experience in the management of common psychiatric disorders (not unlike primary care physicians and emergency medicine physicians, who “see” a lot of psychiatric presentations and have some idea of how to at least prescribe medications for straightforward presentations) The Solution to the Clinical Challenges of Dual Diagnosis • Integrated Clinical Services • Knowledgeable/Competent Staff: • “Dually Licensed” • Training • Supervision • Finances Traditional Approaches (= often ineffective) • Non-existent • Separate/Sequential • Concurrent Ideal: Integrated Integrating Care for Dual Diagnosis Rogers Memorial Hospital Rogers Behavioral Health System Herrington Recovery Center Michael M. Miller, MD, FASAM, FAPA mmiller@rogershospital.org 800-767-4411 rogershospital.org Anxiety and Addiction • A lot of people with addiction are anxious • A lot of people with addiction • “self-medicate” their anxiety • A lot of people with addiction have • anxiety disorders, OCD, PTSD • Is it true “dual diagnosis”? • What are these conditions? • How often to they occur? Addiction • DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria – Substance Dependence – Substance Abuse – Substance Use Disorders – Substance Related Disorders • Intoxication • Withdrawal • Substance Induced Disorders • The ASAM Definition of Addiction DSM-IV Criteria “Substance Dependence” 1. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. a need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication or the desired effect, or b. markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance 2. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. the characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance, or b. the same (or closely related) substance is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms 3. The substance is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended 4. There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use DSM-IV Criteria “Substance Dependence” 5. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from its effects 6. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use 7. The substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance DSM-IV Criteria “Substance Abuse” 1. A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by one (or more) of the following, occurring within a 12-month period: a. recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home b. recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous c. recurrent substance-related legal problems d. continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance 2. The symptoms have never met the criteria for Substance Dependence for this class of substance. (major impact on epidemiological research) Substance Use Disorder Criteria: DSM-IV Abuse Dependence Failure to fulfill obligations X -- Hazardous use X Substance-related legal problems X -- Social/interpersonal substance-related problems X -- Tolerance -- X Withdrawal -- X Persistent desire/unsuccessful efforts to cut down -- X Using more or over for longer than was intended -- X Neglect of important activities -- X Great deal of time spent in substance activities -- X Psychological/Physical use-related problems -- X 1+ criteria 3+ criteria Diagnostic Criteria Diagnostic Threshold American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000. Columbia University Deborah Hasin, Ph.D. 1+ -- 3+ Substance Use Disorder Criteria: DSM-IV and DSM-5 DSM-IV DSM-V Abuse Dependence Substance Use Disorder Failure to fulfill obligations X -- X Hazardous use X -- X Substance-related legal problems X -- -- Social/interpersonal substance-related problems X -- X Tolerance -- X X Withdrawal -- X X Persistent desire/unsuccessful efforts to cut down -- X X Using more or over for longer than was intended -- X X Neglect of important activities -- X X Great deal of time spent in substance activities -- X X Psychological/Physical use-related problems -- X X Craving -- -- X 1+ criteria 3+ Criteria Moderate: 4-5 criteria Severe: 6+ criteria Diagnostic Criteria Diagnostic Threshold Columbia University Deborah Hasin, Ph.D. 11 criteria DSM-5 Substance Use Disorder Tolerance * Withdrawal * More use than intended Craving for the substance Unsuccessful efforts to cut down Spends excessive time in acquisition • Activities given up because of use • • • • • • • not counted if prescribed by a physician or other Rx-er • Uses despite negative effects • Failure to fulfill major role obligations • Recurrent use in hazardous situations • Continued use despite consistent social or interpersonal problems SUD MILD = 2 or more + SUD MODERATE = 4 or more + SUB SEVERE = 6 or more + DSM-5: “Addiction and Related Disorders” – Substance Use Disorders – Substance Related Disorders • Intoxication • Withdrawal • Substance Induced Disorders – Other conditions • Gambling Disorder Addiction American Society of Addiction Medicine • April 2011 Definition of Addiction: “Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors.” Definition of Addiction American Society of Addiction Medicine • April 2011 “Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response. Like other chronic diseases, addiction often involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can result in disability or premature death.” Emotional changes in addiction can include: • Increased anxiety, dysphoria and emotional pain; • Increased sensitivity to stressors associated with the recruitment of brain stress systems, such that “things seem more stressful” as a result; and • Difficulty in identifying feelings, distinguishing between feelings and the bodily sensations of emotional arousal, and describing feelings to other people (sometimes referred to as alexithymia). The emotional aspects of addiction are quite complex. • Some persons use alcohol or other drugs or pathologically pursue other rewards because they are seeking “positive reinforcement” or the creation of a positive emotional state (“euphoria”). • Others pursue substance use or other rewards because they have experienced relief from negative emotional states (“dysphoria”), which constitutes “negative reinforcement.“ • Beyond the initial experiences of reward and relief, there is a dysfunctional emotional state present in most cases of addiction that is associated with the persistence of engagement with addictive behaviors. The state of addiction is not the same as the state of intoxication. When anyone experiences mild intoxication through the use of alcohol or other drugs, or when one engages non-pathologically in potentially addictive behaviors such as gambling or eating, one may experience a “high”, felt as a “positive” emotional state associated with increased dopamine and opioid peptide activity in reward circuits. After such an experience, there is a neurochemical rebound, in which the reward function does not simply revert to baseline, but often drops below the original levels. This is usually not consciously perceptible by the individual and is not necessarily associated with functional impairments. Over time, repeated experiences with substance use or addictive behaviors are not associated with ever increasing reward circuit activity and are not as subjectively rewarding. Once a person experiences withdrawal from drug use or comparable behaviors, there is an anxious, agitated, dysphoric and labile emotional experience, related to suboptimal reward and the recruitment of brain and hormonal stress systems, which is associated with withdrawal from virtually all pharmacological classes of addictive drugs. While tolerance develops to the “high,” tolerance does not develop to the emotional “low” associated with the cycle of intoxication and withdrawal. Thus, in addiction, persons repeatedly attempt to create a “high”--but what they mostly experience is a deeper and deeper “low.” While anyone may “want” to get “high”, those with addiction feel a “need” to use the addictive substance or engage in the addictive behavior in order to try to resolve their dysphoric emotional state or their physiological symptoms of withdrawal. Persons with addiction compulsively use even though it may not make them feel good, in some cases long after the pursuit of “rewards” is not actually pleasurable.5 Although people from any culture may choose to “get high” from one or another activity, it is important to appreciate that addiction is not solely a function of choice. Simply put, addiction is not a desired condition. The Absinthe Drinker, Edward Degas Anxiety • http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseas emanagement/psychiatry-psychology/anxiety-disorder/ • Anxiety is a natural response and a necessary warning adaptation in humans. Anxiety can become a pathologic disorder when it is excessive and uncontrollable, requires no specific external stimulus, and manifests with a wide range of physical and affective symptoms as well as changes in behavior and cognition. Anxiety Disorders (DSM-IV) • Disorders in this Category Generalized Anxiety Disorder [GAD] Panic Disorder (with or without Agoraphobia) Agoraphobia (with or without a history of Panic Disorder) Phobias (including Social Phobia) Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder [OCD] Posttraumatic Stress Disorder [PTSD] Acute Stress Disorder Substance-induced Anxiety Disorder Anxiety secondary to a general medical condition • Disorders outside of this Category Trichotillomania Anxiety Disorders Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders Based on a presentation originally given by Katharine A. Phillips, MD, as part of a master course on the DSM-5 at the American Psychiatric Association 166th Annual Meeting in San Francisco, California on May 18, 2013, and Rogers Memorial Hospital presentations by Bradley C. Riemann, PhD. DSM-5 Chapters • Anxiety Disorders: generalized anxiety disorder; panic disorder; agoraphobia; specific phobia; social anxiety disorder (social phobia), separation anxiety disorder; selective mutism • Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders: obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), hoarding disorder, trichotillomania (hairpulling disorder), excoriation (skin picking) disorder – NEW CHAPTER • Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders: PTSD; acute stress disorder; adjustment disorders; reactive attachment disorder; disinhibited social engagement disorder,– NEW CHAPTER Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) Generalized anxiety disorder is characterized by chronic feelings of excessive worry and anxiety without a specific cause. Individuals with generalized anxiety disorder often feel on edge, tense, and jittery. Someone with generalized anxiety disorder may worry about minor things, daily events, or the future. These feelings are accompanied by physical complaints such as elevated blood pressure, increased heart rate, muscle tension, sweating, and shaking. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), more than 6.8 millions American adults suffer from generalized anxiety disorder. More than twice as many women than men suffer from the disorder. While the disorder can occur at any time throughout the lifespan, it most often arises sometime between childhood and middle age. GAD frequently occurs alongside another problem including other anxiety disorders, substance abuse, or depression. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): Symptoms Excessive worry/no specific source Breathlessness Exaggerated startle reflex Nausea Trembling Inability to sleep due to worrying Excessive sweating Stomach aches Headaches Fatigue Muscle tension Lightheadedness From: http://psychology.about.com/od/ psychiatricdisorders/ Social Anxiety Disorder Social anxiety disorder, also called social phobia, is an anxiety disorder in which a person has an excessive and unreasonable fear of social situations. Anxiety (intense nervousness) and self-consciousness arise from a fear of being closely watched, judged, and criticized by others. A person with social anxiety disorder is afraid that he or she will make mistakes, look bad, and be embarrassed or humiliated in front of others. The fear may be made worse by a lack of social skills or experience in social situations. The anxiety can build into a panic attack. Social Anxiety Disorder In addition, people with social anxiety disorder often suffer "anticipatory" anxiety -- the fear of a situation before it even happens -- for days or weeks before the event. In many cases, the person is aware that the fear is unreasonable, yet is unable to overcome it. People with social anxiety disorder suffer from distorted thinking, including false beliefs about social situations and the negative opinions of others. Without treatment, social anxiety disorder can negatively interfere with the person's normal daily routine, including school, work, social activities, relationships. Social Anxiety Disorder People with social anxiety disorder may be afraid of a specific situation, such as speaking in public. However, most people with social anxiety disorder fear more than one social situation. Other situations that commonly provoke anxiety include: • Eating or drinking in front of others. • Writing or working in front of others. • Being the center of attention. • Interacting with people, including dating or going to parties. • Asking questions or giving reports in groups. • Using public toilets. • Talking on the telephone. Social Anxiety Disorder Social anxiety disorder may be linked to other mental illnesses, such as panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and depression. In fact, many people with social anxiety disorder initially see the doctor with complaints related to these disorders, not because of social anxiety. What Are the Symptoms of Social Anxiety Disorder? Many people with social anxiety disorder feel that there is "something wrong," but don't recognize their feeling as a sign of illness. Symptoms of social anxiety disorder can include: • Intense anxiety in, or avoidance of, social situations. • Physical symptoms of anxiety, including confusion, pounding heart, sweating, shaking, blushing, muscle tension, upset stomach, and diarrhea. Panic Disorder • Panic disorder is different from the normal fear and anxiety reactions to stressful events. • It strikes without reason or warning. • Symptoms of panic disorder include sudden attacks of fear and nervousness, as well as physical symptoms such as sweating and a racing heart. During a panic attack, the fear response is out of proportion for the situation, which often is not threatening. Over time, a person with panic disorder develops a constant fear of having another panic attack, which can affect daily functioning and general quality of life. • Panic disorder often occurs along with other serious conditions, such as depression, alcoholism, or drug abuse. http://www.webmd.com/anxiety-panic/guide/mental-health-panic-disorder Panic Disorder Symptoms of a panic attack, which often last about 10 minutes, include: • • • • • • • • • • • Difficulty breathing Beyond the panic attacks Pounding heart or chest pain themselves, a key symptom of Intense feeling of dread panic disorder is the persistent fear of having future panic Sensation of choking or smothering attacks. The fear of these Dizziness or feeling faint attacks can cause the person Trembling or shaking to avoid places and situations Sweating where an attack has occurred or where they believe an attack Nausea or stomachache may occur. Tingling or numbness in the fingers and toes Chills or hot flashes A fear that you are losing control or are about to die DSM-5 Changes for Anxiety Disorders • Panic Disorder: – “Panic disorder with agoraphobia” and “Panic disorder without agoraphobia” are combined into one disorder named “Panic disorder” – Clarifies that panic attacks can arise from a calm or anxious state • Separation Anxiety Disorder: Criteria slightly modified to make them more applicable to adults, and moved to Anxiety Disorders section Craske et al, 2010, Bogels et al, in press DSM-5 Changes for Agoraphobia, Social Phobia, and Specific Phobia • More consistency across the phobias – e.g., all emphasize fear, anxiety, avoidance • 6-month duration added to ensure not a transient, normal experience • Name change: social anxiety disorder (social phobia) • Insight: – Social anxiety disorder and specific phobia no longer require that the patient recognizes that the fear is excessive or unreasonable → replaced with phrasing that makes this the clinician’s judgment – But insufficient research to add an insight specifier Craske et al, 2010 Some Changes for Anxiety Disorders • Selective Mutism: – Moved to Anxiety Disorders section – Criteria unchanged from DSM-IV • OCD and PTSD – Moved to their own separate chapters – Some other conditions brought into those groupings New Disorders in Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders Hoarding disorder Excoriation (skin picking) disorder Why Add Hoarding Disorder to DSM-5? • Substantial scientific literature on this disorder • Fear they’ll discard something they’ll need at a later date, and don’t trust their decision-making regarding sorting items into ‘save’ vs. ‘toss’ • Clinically significant hoarding is prevalent (2-5% of the population) and can be severe, with resulting legal problems • Most hoarders (up to 80%) do not meet diagnostic criteria for OCD and do not endorse other clinically significant OCD symptoms • There are important differences between hoarding and OCD across a number of validators, including poorer response to SRIs and ERP Mataix-Cols, Frost, Pertusa, et al: Depress Anxiety, 2010 Specifiers for Hoarding Disorder • With Excessive Acquisition: Excessive acquisition of items that are not needed or for which there is no available space • Insight: – Good or fair insight – Poor insight – Absent insight/delusional beliefs Trichotillomania (Hair-Pulling Disorder) Core feature: Recurrent pulling out of one’s hair, resulting in hair loss Changes: • Hair loss does not have to be noticeable • Criteria B and C deleted (tension/gratification) • Replaced with “repeated attempts to decrease or stop” hair pulling • Hair Pulling Disorder (in parentheses) added to the name Stein et al, 2010 Why Add Excoriation (Skin Picking) Disorder to DSM-5? • Substantial scientific literature on this disorder • Clinically significant skin picking affects 1-2% of the population • This problem can be severe, with resulting medical sequelae such as infections, lesions, scarring, and physical disfigurement • This condition is not covered by any other disorders in DSM Stein, et al: Depress Anxiety, 2010 Excoriation (Skin Picking) Disorder Features: • Recurrent skin picking resulting in skin lesions (which can be concealed) • Repeated attempts to decrease or stop skin picking • Causes clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning Excoriation (Skin Picking) Disorder, continued • Skin picking is not attributable to physiologic effects of a substance (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine) or another medical condition (e.g., scabies) • Not better explained by symptoms of another mental disorder, such as: – Psychotic disorder (e.g., parasitosis) – Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD): picking to improve perceived skin defects or flaws – Stereotypic movement disorder – Non-suicidal self-injury: intent to harm oneself Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD; 300.3) • DSM-V has created a new “Chapter” entitled Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders. No longer placed in Anxiety Disorders Chapter. – OCD. – Body Dysmorphic Disorder. – Hoarding Disorder. – Trichotillomania (Hair-pulling Disorder). – Excoriation Disorder (skin picking). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) • OCD characterized by either obsessions or compulsions (or both). Obsessions • Recurrent, and persistent thoughts, urges, or images that are experienced as intrusive and unwanted and cause marked anxiety or distress. • Person attempts to ignore or suppress obsessions or to neutralize them with some other thought or action (i.e., compulsion). Examples of Obsessions • Contamination (1). • Repeated doubt (2). • Need for exactness or symmetry. • Need to tell, ask, or confess. • Harming. • Sexual imagery. • Religious. Compulsions • Repetitive behaviors or mental acts that the person feels driven to perform in response to an obsession, or according to rules that must be applied rigidly (i.e., ritual). • Aimed at preventing or reducing distress or preventing some dreaded event or situation; however, these compulsions either are not connected in a realistic way or are clearly excessive. Examples of Compulsions • Checking (1). • Washing or cleaning (2). • Counting. • Ordering. • Repeating. • Praying. • Requesting assurance. “Either” / “And” Questions • DSM Criteria states that to have OCD, you need either obsessions or compulsions. • Symptom presentation (historical). – Mixed – “Pure” obsessional – “Pure” compulsive = 98% = < 2% = < 0.5% • Doesn’t seem to match clinical experience at Rogers. • Leonard & Riemann, 2012. – Found that all 1,086 individuals in sample with OCD reported having both (746 adults, 340 children). • Suggest changing to “and”. Some Changes for OCD • Definition of obsession: “urge” replaces “impulse” • “Unwanted” replaces “inappropriate” (different cultures have different definitions of inappropriate) • Changed to “in most individuals, causes marked anxiety or distress” • New tic-related specifier: Current or past history of a tic disorder Leckman, Denys, Simpson, et al, 2010 Diagnosis in OCD • Specify if: – With good or fair insight. • Recognizes that OCD related beliefs are definitely or probably not true (good) or that they may or may not be true (fair). – With poor insight. • Thinks OCD related beliefs are probably true. – With absent insight/ delusional beliefs. • Completely convinced OCD related beliefs are true. Insight in OCD per DSM-5 1. Patients no longer must recognize that their OCD obsessions or compulsions are excessive or unreasonable • Neither “excessive” nor “unreasonable” were defined or operationalized in DSM-IV, and they can have different meanings • Some patients lack insight (indeed, DSM-IV has a “poor insight” specifier) 2. Delusional variants of OCD (and BDD) are no longer in the psychosis section; they are only with OCD (and BDD) 3. OCD’s poor insight specifier has been expanded to include a broader range of insight options, including delusional OCD beliefs Leckman, Denys, Simpson, et al, 2010; Phillips et al, 2010 Body Dysmorphic Disorder Core feature: Distressing or impairing preoccupation with perceived appearance defects or flaws that are not observable or appear slight to others Changes: • New Criterion B: Requires repetitive BDD behaviors • Insight specifier: Good/fair, poor, absent insight/delusional beliefs • Muscle dysmorphia specifier: Small or insufficiently muscular body build Phillips et al, 2010 OCD (continued) • Specifier if: – Tic-related. • Individual has current or past history of a tic disorder. • There is an INSIGHT specifier. Commonly Asked Questions • How common is it? 2.5% • Any sex differences? No • Age of onset? 20.2 yrs. (males) 1-14 years 22% – 15-24 years 42% – 25-34 years 21% – over 35 years 15% – over 50 years Rare – Commonly Asked Questions (continued) • Course of OCD? – 85% continuous course with minor fluctuations. – 15% deteriorating course. • Stress play a role? – 50-60% report stressful trigger around onset. – Almost all report increase in symptoms during stress. Associated Features • Secondary depressed mood (85%). • Academic and occupational impairment. • Low self-esteem. • Social withdrawal. • Family discord. • Fear of embarrassment (hide symptoms). • Avoidance. Leading Causes of Disability (WHO) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Major Depression. Iron-deficiency anemia. Falls. Alcohol use. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Bipolar disorder. Congenital anomalies. Osteoarthritis. Schizophrenia. OCD. What is Not OCD? • Pathological gambling. • Kleptomania. • Substance abuse disorders. • Certain sexual behaviors. – Thoughts are not unwanted. – Derive pleasure from “compulsive” act. – Typically, only want to stop because of negative consequences of acts. What is Not OCD? (continued) • Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD). – Collection of personality traits. – Preoccupation with orderliness, control, rigidity, and inflexibility (rules, lists, schedules) – Does not involve obsessions or compulsions. – May like. OCD-Spectrum Disorders • Broader than “OC-related disorders”. • High degree of symptom overlap. • High rate of comorbidity. • Family History. • Treatment overlap. – Common underlying neurobiological mechanisms? OCD-Spectrum Disorders (continued) • Trichotillomania (hair pulling disorder). – Recurrent pulling out of one’s hair. – May play with, chew on, or ingest. – May nail bite and skin pick. • No obsessions nor rules that have to be applied rigidly. OCD-Spectrum Disorders (continued) • Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD). – Preoccupation with an imaged or exaggerated defect in physical appearance (e.g., nose is too big). • BDD within Eating Disorders – One could say Eating Disorders are part of the “spectrum” but they are categorized separately in the DSM system and always have been. OCD-Spectrum Disorders (continued) • Eating Disorders. – Anorexia Nervosa (Refusal to maintain normal body weight). – Bulimia Nervosa (Repeated episodes of binge eating followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviors (e.g., excessive exercise). – Disturbance in perception of body shape and weight. Does Genetics Play a Role? • 20% of first-degree relatives will have OCD. • Additional 15% will have “subclinical” symptoms. • Does not appear to be learned (phenotypes different). Summary • OCD is a common and debilitating condition. • Key element of effective treatment is Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP). • Keys to effective exposure therapy include prolonged, repetitive and graduated exposure. Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders • New Chapter in DSM-5, not just in Anxiety Disorders chapter • Includes conditions other than PTSD and Acute Stress Disorder (DSM-IV), a.k.a. “psychological shock” – Reactive Attachment Disorder – All of the Adjustment Disorders (moved into this chapter) PTSD Criteria in DSM-5 A. The person was exposed to the following event(s): death or threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violation, in one or more of the following ways: 1. Experiencing the event(s) him/herself 2. Witnessing, in person, the event(s) as they occurred to others PTSD Criteria in DSM-5 3. Learning that the event(s) occurred to a close relative or close friend; in such cases the actual or threatened death must have been violent or accidental. 4. Experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the event(s) (e.g., first responders collecting body parts; police officers repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse); this does not apply to exposure through electronic media, television, movies or pictures unless this exposure is work-related. PTSD Criteria in DSM-5 B. Re-experiencing symptoms (recurrent memories/dreams/nightmares, flashbacks, physical re-experiencing, high anxiety) C. Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma (internal cues and external cues) D. Negative alterations in cognitions and mood that are associated with the traumatic event (inability to remember, exaggerated negative beliefs, blaming self, negative emotional state, emotional numbing, diminished interests, detachment from others, inability to love or enjoy) PTSD Criteria in DSM-5 E. Alterations in arousal and reactivity that are associated with the traumatic event (irritable, reckless, hypervigilence, heightened startle, decreased concentration, sleep disturbance) F. Duration of the disturbance is more than one month G. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning More Detail on Criterion D. Negative Cognitions & Mood 1. inability to remember important aspects of the event (“dissociative amnesia”) 2. Persistent and exaggerated negative expectations and beliefs about oneself, others or the world (e.g. “I am bad,” “No one can be trusted,” “My whole nervous system is permanently ruined,” “The world is completely dangerous” (C7) 3. Persistent distorted blame of self or others about the cause or consequences of the traumatic event (e.g. self-blame) (NEW) 4. Persistent negative emotional state (for example: fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame) (NEW) More Detail on Criterion E. Alterations in Arousal & Reactivity 1. Irritable or aggressive behavior (e.g. yelling at other people, getting into fights or destroying things (revised D3) 2. Reckless or self-destructive behavior (e.g. driving too fast or while intoxicated, heavy drug or alcohol use, risky sexual behavior, or trying to injure or harm oneself). (NEW) 3. Hypervigilance 4. Exaggerated startle response. 5. Trouble with concentration. 6. Trouble with sleep onset, staying asleep, or restlessness during sleep DSM-5: Acute Stress Disorder A. PTSD “Criterion A” (sub-criteria 1, 2, 3, 4) B. No mandatory (e.g., dissociative, etc.) symptoms from any cluster C. Nine (or more) of the following 14 items (with onset or exacerbation after the traumatic event): – Intrusion Symptoms (4) – Negative Mood (1) – Dissociative Symptoms (2) – Avoidance Symptoms (2) – Arousal Symptoms(5) Are we Dealing with Horses or Zebras? • Common conditions • Common presentations • Uncommon conditions • Uncommon presentations www.publichealth.va.gov • Epidemiology is the study of health in populations to understand the causes and patterns of health and illness. Epidemiology (per the World Health Organization) The study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events (including disease), and the application of this study to the control of diseases and other health problems. Epidemiology The branch of medical science that investigates all the factors that determine the presence or absence of diseases and disorders. Terms in Epidemiology • Incidence: The number of new cases of a disease or disorder in a population over a period of time. • Prevalence: The number of existing cases of a disease in a population at a given time. • Burden of disease: The total significance of disease for society, beyond the immediate cost of treatment. It is measured in years of life lost to ill health, or the difference between total life expectancy and disability-adjusted life expectancy (DALY). (Adapted from the World Health Organization.) Sources of Epidemiological Data • ECA (Epidemiologic Catchment Area) Study--1980’s i.e., DSM-III criteria used • NCS (National Comorbidity Study)—1994 i.e., DSM-III-R criteria used • NCS-R (NCS-Replication)—2003 i.e., DSM-IV criteria used • NESARC (National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions Comorbidity) Study — 2005 Data from NCS-R • Among all Axis I Mental Disorders, the most common are ANXIETY DISORDERS (18% -- 12-month prevalence) and MOOD DISORDERS (9.5%) and SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS. • Anxiety Disorders: – Social Anxiety (12-month prevalence) = 6.8% – Specific Phobia (12-month prevalence) = 8.7% Kessler RC, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6):617-27, 2005 Prevalence and Co-occurrence of Substance Use Disorders and Independent Mood and Anxiety Disorders: Results from the NESARC Grant BF, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-16, 2004. National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions • Anxiety disorders occur in 18% to 28% of the US general population during any 12-month period. • In anxiety disorder, there is a 33% to 45% 12-month prevalence rate for a comorbid substance use disorder (SUD) • For patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), the lifetime prevalence of comorbid alcohol abuse and dependence is 30% to 35%, and the prevalence of drug abuse and dependence is 25% to 30%. Grant BF, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-16, 2004. • Among individuals with SUDs, independent DSM-IV diagnoses of mood or anxiety disorders can be made in 2 ways. – First, the full mood or anxiety syndrome is established before substance use. – Second, the mood or anxiety syndrome persists for more than 4 weeks after the cessation of intoxication or withdrawal. Grant BF, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-16, 2004. 12-month prevalence: • Any SUD = 9.35% • Rates of “Substance Abuse” a bit higher than rate of “Substance Dependence” • Alcohol Use Disorder (DSM-IV abuse or dependence) = 8.46% • Drug Use Disorder (DSM-IV abuse or dependence) = 2.00% – Cannabis Use Disorder = 1.45% – Opioid Use Disorder = 0.35% Grant BF, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-16, 2004. • Anxiety Disorders are more strongly associated with Substance Dependence than with “Drug Abuse” • Among Anxiety Disorders, Panic Disorder with Agoraphobia was mot strongly associated with Substance Use Disorders • Of those with Any SUD, 17.7% had at least one independent Anxiety Disorder Grant BF, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-16, 2004. Alcohol Dependence: – GAD (Generalized Anxiety) 5.69% – Social Anxiety 6.25% – Panic Disorder (combined w/ and w/o agoraphobia) 6.54% – Specific Phobia 13.84% • Drug Dependence: – GAD (Generalized Anxiety) 17.22% – Social Anxiety 12.91% – Panic Disorder (combined w/ and w/o agoraphobia) 15.63% – Specific Phobia 22.26% Grant BF, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-16, 2004. Treatment Seeking: • Among those with any independent anxiety disorder in a 12month period, 12.1% sought professional help • Among those with any independent mood disorder in a 12month period, 25.8% sought professional help • Among those with an alcohol use disorder in a 12-month period, 5.8% sought professional help • Among those with a drug use disorder in a 12-month period, 13.1% sought professional help Grant BF, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-16, 2004. “Dual Diagnosis” among treatment seekers: • Among those with GAD in the past 12 months who sought treatment for it, 15.9% had SUD • Among those with Social Anxiety Disorder in the past 12 months who sought treatment for it, 21.3% had SUD • Among those with Panic Disorder in the past 12 months who sought treatment for it, 15.4-21.9% had SUD • Among those with Specific Phobia in the past 12 months who sought treatment for it, 16.0% had SUD • Among those with Any Independent Anxiety Disorder in the past 12 months who sought treatment for it, 16.5% had SUD – By roughly 2:1, more of these people had Alcohol Use Disorder than Drug Use Disorder Grant BF, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-16, 2004. “Dual Diagnosis” among treatment seekers: • Among those with Alcohol Use Disorder in the past 12 months (5.8% of those surveyed in NESARC), the rates of Anxiety Disorders are high: – GAD = 12.35% – Social Anxiety Disorder = 8.49% – Panic Disorder = 4.1 - 9.1% – Specific Phobia = 17.24% – Any Anxiety Disorder = 33.38% • Among those with Drug Use Disorder in the past 12 months (13.1% of those surveyed in NESARC), the rates of Anxiety Disorders are high: – GAD = 22.07% – Social Anxiety Disorder = 12.09% – Panic Disorder = 5.9 – 8.6% – Specific Phobia = 22.52% – Any Anxiety Disorder = 42.63% Grant BF, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-16, 2004. – About 18% of all persons in the general population who have a current SUD have a current independent Anxiety Disorder of some type – About 15% of individuals with at least one 12-month independent Anxiety Disorder have a Substance Use Disorder Grant BF, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-16, 2004. – The prevalence of substance-induced anxiety disorder was about 1% of the general population “These results strongly suggest that treatment for mood or anxiety disorder should not be withheld from those with substance use disorders in stable remission on the assumption that most of these disorders are due to intoxication or withdrawal” (i.e., are “substance-induced” conditions). Grant BF, et al. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-16, 2004. “Taken together, the NESARC results provide clear and persuasive evidence that mood and anxiety disorders must be addressed by alcohol and drug treatment specialists, and that substance use disorders must be addressed by primary care physicians and mental health treatment specialists.” E. Jane-Llopis & I. Matytsina. Drug and Alcohol Review 25:515-35, 2006 “Co-occurrence of current Substance Use Disorders and personality disorders were pervasive in the US population. Up to 39% of those with alcohol dependence and up to 69% of those with drug dependence had a comorbid personality disorder of any type.” (citing B.F. Grant, et al, Archives of General Psychiatry 61:361-68, 2004) [WHO Regional Office for Europe] E. Jane-Llopis & I. Matytsina. Drug and Alcohol Review 25:515-35, 2006 The International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology study, based on six large epidemiological studies, identified that, on average, 25% of those cases of [alcohol abuse] and 32% of those cases of alcohol dependence had a lifetime history of anxiety disorder. [WHO Regional Office for Europe] E. Jane-Llopis & I. Matytsina. Drug and Alcohol Review 25:515-35, 2006 It is more likely for people with alcohol dependence or drug dependence to suffer from a comorbid mental disorder than vice versa. “The evidence for the onset of anxiety disorders after a substance use disorder is less strong, and the available evidence points towards the opposite direction.” [WHO Regional Office for Europe] Addiction and Anxiety How do you treat Addiction? Treatment of Addiction Specialty Treatment Levels of Care (ASAM PPC) • • • • General Outpatient Intensive Outpatient/Day Treatment Residential Hospital Components of Comprehensive Drug Abuse Treatment Child Care Services Family Services Vocational Services Intake Processing / Assessment Housing / Transportation Services Behavioral Therapy and Counseling Clinical and Case Management Financial Services Treatment Plan Substance Use Monitoring Pharmacotherapy Self-Help / Peer Support Groups Mental Health Services Medical Services Continuing Care Legal Services AIDS / HIV Services Educational Services Treatment of Addiction • Abstinence is the standard treatment goal for addiction • Treatment includes – Psychosocial Rehabilitation • (various methods of counseling/psychotherapy) – Pharmacotherapy – Self-Help as an adjunct Non-Pharmacological Tx • • • • • • • • • • • Addiction Counseling (supportive / RET / confrontational) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Coping Skills Training Recreational Therapy Psychoanalytically-oriented Psychotherapy Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) Community Reinforcement Approach (CRAFT) Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF) Network Therapy Behavioral Therapy Aversion Therapy Standard Treatment Components • Milieu therapy • General alcoholism counseling • Educational lectures and films • Introduction to and Referral to Alcoholics Anonymous Targeted Therapeutic Changes in Addiction Treatment BEHAVIORAL CHANGES BIOLOGICAL CHANGES • Eliminate alcohol and other drug use behaviors • Eliminate other problematic behaviors • Expand repertoire of healthy behaviors • Develop alternative behaviors • Identify triggers for using behaviors/relapses • Resolve acute alcohol and other drug withdrawal symptoms • Physically stabilize the organism • Develop sense of personal responsibility for wellness • Initiate health promotion activities (e.g., diet, exercise, safe sex, sober sex) • Address cravings through medical interventions (treatment medications) Targeted Therapeutic Changes in Addiction Treatment COGNITIVE CHANGES AFFECTIVE CHANGES • Increase awareness of illness • Increase awareness of negative consequences of use • Increase awareness of addictive disease in self • Decrease denial • Increase emotional awareness of negative consequences of use • Increase ability to tolerate feelings without defenses • Manage anxiety and depression • Manage shame and guilt Targeted Therapeutic Changes in Addiction Treatment SOCIAL CHANGES SPIRITUAL CHANGES • Increase personal responsibility in all areas of life • Increase reliability and trustworthiness • Become resocialized: reestablished sober social network • Increase social coping skills: with spouse/partner, with colleagues, with neighbors, with strangers • Increase self-love/esteem; decrease self-loathing • Reestablish personal values • Enhance connectedness • Increase appreciation of transcendence Taken from: Miller, Michael M. Principles of Addiction Medicine, 1994; published by American Society of Addiction Medicine, Chevy Chase, MD Evidence Based Psychotherapies • Twelve-Step Facilitation (not just “go to A.A.”) – Explain/educate – Promote attendance/participation – Explore experiences: Attendance? Participation? Barriers? – Reflect, process, problem-solve – Working the Steps – Working with a Sponsor What can AA do for you? Follow the Steps 1. We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable. 2. Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity. 3. Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over… 4 .Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves. 5. Admitted the exact nature of our wrongs (and stated this openly to another human begin) 6. Were entirely ready to have…all these defects of character [removed]. 7. [Humbly asked to have these shortcomings removed ]. 8. Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all. 9. Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others. AA Meetings • Types – Open – Closed • Structure – Speaker meeting – Discussion meeting – Step meeting – Big Book meeting – Beginners’ meeting – Couples meetings – ‘Professionals meetings’ / Caduceus Underlying Premises of AA 1. The primary goal of AA is to help people achieve longterm abstinence through mutual self-help groups. 2. Alcoholism is a medical disease, not a moral deficiency. 3. Alcoholism is a progressive, often fatal, condition with exacerbations and remissions that can be arrested but not cured. 4. Lifelong abstinence is necessary for long term recovery 5. Recovery involves addressing the physical, emotional and spiritual problems associated with alcoholism. 6. Recovery is a long term process, not a single event. Evidence Based Psychotherapies • Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF) • Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) • Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) • Contingency Management MET (Motivational Enhancement Therapy) • What concerns you? • What are you using? • Do you see a problem, a link? • Help patient see the problem, the link. • Get them to start contemplating the issue, gradually move them to start contemplating change, to begin planning for change… Readiness for Change Stages of Change • • • • • Precontemplative Contemplative Preparation Action Maintenance MOTIVATIONAL ENHANCEMENT THERAPY moves the person along the stages of change…. Motivational Interviewing (M.I.) • Identify what the patient wants • Identify what you want • Try to get the patient’s goals and the therapist’s goals to align General Principles of M.I. • Express Empathy: this guides therapists to share with clients their understanding of the clients' perspective. • Develop Discrepancy: this guides therapists to help clients appreciate the value of change by exploring the discrepancy between how clients want their lives to be vs. how they currently are (or between their deeply-held values and their day-to-day behavior). General Principles of M.I. • Roll with Resistance: this guides therapists to accept client reluctance to change as natural rather than as pathological. • Support Self-efficacy: this guides therapists to explicitly embrace client autonomy (even when clients choose to not change) and help clients move toward change successfully and with confidence. Motivational Interviewing: Advantages of Change (Start with Rogerian self-regard — empathetically engage around their current situation and how they feel about it) How would you like for things to be different? What would be the good things about losing weight? What would you like your life to be like 5 years from now? If you could make this change immediately, by magic, how might things be better for you? • The fact that you’re here indicates that at least part of you thinks it’s time to do something. What are the main reasons you see for making a change? • What would be the advantages of making this change? • • • • Motivational Interviewing: Disadvantages of the status quo (Develop Discrepancy: increase their cognitive dissonance about staying where they are) • What worries you about your current situation? • What makes you think that you need to do something about your blood pressure? • What hassles have you had in relation to your drug use? • What is there about your drinking that you or other people might see as reasons for concern? • In what way does this concern you? • How has this stopped you form doing what you want to do in life? • What do you think will happen if you don’t change anything? Motivational Interviewing: Optimism about change • What makes you think that if you did decide to make a change, you could do it? • What encourages you that you can change if you want to? • What do you think would work for you, if you decided to change? • When else in your life have you made a significant change like this? How did you do it? • How confident are you that you can make this change? • What personal strengths do you have that will help you succeed? • Who could offer you helpful support in making this change? Motivational Interviewing: Intention to change • What are you thinking about your gambling at this point? • I can see that you’re feeling stuck at the moment. What is going to have to change? • What do you think you might do? • How important is this to you to lose weight? How much do you want to do this? • What would you be willing to try? • Of the options I’ve mentioned, which one sounds like it fits you best? • Never mind the “how” for right now – what do you want to have happen? • So what do you intend to do? Principles of CBT • Thoughts • Behaviors • Emotions • Other lingo = ABC (Affect, Behaviors, Cognitions) • If you’re depressed or anxious, it could relate to what you think/believe, and what you’re doing • DO IT DIFFERENTLY • RE-THINK IT CBT • Behavioral Journals/Logs • Thought Journals/Logs • Feelings Journals/Logs Thought Challenging (irrational/un-useful T’s) Cognitive Reframing Behavior Change: Do It Different! Do things that make you feel successful/happy. www.drugabuse.gov NIDA Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment (1999, rev 2009) 1. Addiction is a complex but treatable disease that affects brain function and behavior. Drugs of abuse alter the brain’s structure and function, resulting in changes that persist long after drug use has ceased. 2. No single treatment is appropriate for everyone. NIH Publication No. 09–4180 The ASAM Criteria and ASAM Criteria Software The ASAM Criteria • Intensity of Service should derive from Severity of Illness • Treatment should follow multidimensional Assessment • Diagnosis—Treatment Plan— Determination of Level of Care Assessment Dimensions • Intoxication/Withdrawal Potential • Biomedical Conditions/Complications • Emotional/Behavioral/Cognitive Conditions • Treatment Acceptance/Readiness/Motivation • Relapse/Continued Use Potential • Recovery Environment Levels of Care • 0.5 Screening/Brief Intervention/Education • 1.0 General Outpatient • 2.0 Intensive Outpatient/Partial Hospital • 3.0 Medically Monitored/Residential – halfway houses, extended care, TC’s • 4.0 Medically Managed/Inpatient • In some cases of addiction, medication management can improve treatment outcomes. • In most cases of addiction, the integration of psychosocial rehabilitation and ongoing care with evidence-based pharmacological therapy provides the best results. • Chronic disease management is important for minimization of episodes of relapse and their impact. • Treatment of addiction saves lives Using DRUGS to treat Drug Addiction Addiction • Nicotine—pharmacotherapy is available • Opioids—pharmacotherapy is available • Alcohol—pharmacotherapy is available • Sedatives • Stimulants • Cannabinoids • Hallucinogens • Inhalants • Gambling Overview of Pharmacotherapies for Addiction • Antabuse—for alcohol addiction • Naltrexone, acamprosate, gabapentin, topiramate, et al.—for alcohol addiction • Naltrexone—for opioid addiction • Opioid Agonist Therapies—MMT • O.B.O.T.—buprenorphine • N.R.T., bupropion, varenicline—for nicotine addiction Addiction and Anxiety How do you treat Anxiety? How do you treat Anxiety? • Psychotherapy • Pharmacotherapy • Complimentary/Alternative Medicine Treatment of Anxiety Disorders • Pharmacotherapy • Supportive Therapy • Psychoanalytically-oriented Psychotherapy • Behavioral Therapy (ERP) • Cognitive Behavioral Therapy – A. Timothy Beck, PhD., University of Pennsylvania – “Cognitive Therapy of Depression”, 1979 – Broad applicability/utility: depression, anxiety, phobias, addiction, OCD, eating disorders Bradley C. Riemann, PhD Clinical Director, OCD Center and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Services Principles of CBT • Thoughts • Behaviors • Emotions • Other lingo = ABC (Affect, Behaviors, Cognitions) • If you’re depressed or anxious, it could relate to what you think/believe, and what you’re doing • DO IT DIFFERENTLY • RE-THINK IT CBT • Behavioral Journals/Logs • Thought Journals/Logs • Feelings Journals/Logs Thought Challenging (irrational/un-useful T’s) Cognitive Reframing Behavior Change: Do It Different! Do things that make you feel successful/happy. Pharmacotherapy for Anxiety • Benzodiazepines • Other sedative-hypnotics • Other agents – buspirone (BuSpar®) – Antihistamines (Benadryl®) – clonidine – gabapentin – atypical antipsychotics – beta-blockers (propranolol, atenolol) Pharmacotherapy for Anxiety • NO TO Benzodiazepines • Serotonin drugs – SSRI – SNRI – Tricyclic antidepressants (TCADs) – MAOIs • Bupropion (Wellbutrin®) Medications Advantages: • • • • Easy to do. Effective. Safe long-term. Accessible. Disadvantages: • Potential side effects. – Anafranil (constipation, blurred vision, sedation, tremor). – Others (insomnia, agitation, nausea, sexual) • Do not act quickly. • Rarely eliminates symptoms (expect 30%). • High relapse rates (80% in 7-12 weeks). • Noncompliance Behavior Therapy (BT) • Exposure and Response/Ritual Prevention (ERP) is the key element. – Meyer (1966). – Based on the principle of habituation. – Habituation is the decrease in anxiety experienced with the passage of time. Behavior Therapy (continued) • Exposure is placing an individual in feared situations (targets the obsessions). – Needs to be prolonged enough to lead to within trial habituation (at least 50% reduction in anxiety). – Needs to be repetitive enough to lead to between trial habituation (until causes minimal to no anxiety). – Needs to be graduated (increases compliance). Types of Exposures • Imaginal exposure. – Conduct exposure in imagination. – Conduct exposure with electronically recorded scenerios. • In vivo Exposure. – Real-life exposure. – Typically more effective. – Go out into the community. – Imaginal approach is important when in vivo is determined to be impractical, dangerous, or anxiety-unmanageable. Types of Exposures (continued) • Self-Exposure. – Conducted by patient alone. • Therapist-Aided Exposure. – Both therapist and patient perform or while therapist is present. Behavior Therapy (continued) • Ritual Prevention is blocking the typical response or ritual before, during, and after exposure so habituation can take place (targets compulsions). – Replace the ritual with habituation as way of controlling anxiety. Treatment Steps • Assessment Phase. – Initial evaluation (1 hour). – Confirm diagnosis. – Identify problem areas (e.g., door knobs). – Assess for comorbid diagnoses. – Educate patient and family about the patient’s specific diagnosis, and treatment options. Cognitive Restructuring • Used as an addition to ERP. • Global targets. – Increasing tolerance of uncertainty. – Decreasing perceived need to control thoughts (e.g., suppression of unwanted thoughts). – Decreasing the perceived importance of thoughts. Cognitive Restructuring • Specific targets. – Attempts to identify and correct “errors” in thinking. • Probability Overestimation Errors (e.g., contracting AIDS from not washing hands). • Catastrophizing Errors (e.g., checkout person not groomed well). Effectiveness of ERP • 97% of patients experience habituation with ERP. • Foa (1996) meta-analysis of 12 studies with 330 patients. – 83% much or very much improved. • Greist (1996) compared 18 studies with 294 patients. – Average decrease in YBOCS of 11.8 (SRI’s=7.5). Effectiveness of ERP (continued) • Low relapse rates with ERP. – Foa (1996) 16 studies with 376 patients found 76% much or very much improved at follow-up (average 2.5 years). • 50% of “medication relapsers” can discontinue SRI’s if add ERP. • Many believe ERP is “first-line” treatment. Effectiveness of Rogers’ IOP • Adults. – Admitting Y-BOCS 25.9 – Discharge Y-BOCS 13.7 (-47.1%) – Admitting BDI-2 25.7 – Discharge BDI-2 11.2 (-56.4%) Residential Treatment at Rogers • Kids. – Admitting CY-BOCS – Discharge CY-BOCS – Admitting CDI – Discharge CDI 22.0 8.2 (-62.7%) 11.3 6.3 (-44.3%) Residential Treatment at Rogers • Adolescents. – Admitting CY-BOCS 26.1 – Discharge CY-BOCS 13.6 (-47.8%) – Admitting BDI-2 20.4 – Discharge BDI-2 8.0 (-60.6%) Residential Treatment at Rogers • Adults. – Admitting Y-BOCS 28.4 – Discharge Y-BOCS 16.5 (-41.9%) – Admitting BDI-2 28.8 – Discharge BDI-2 12.6 (-56.2%) Co-Morbid Program at Rogers • Adults – Admitting Y-BOCS 24.6 – Discharge Y-BOCS 13.3 (-45.9%) – Admitting BDI-2 32.6 – Discharge BDI-2 15.4 (-52.8%) Oconomowoc Residential Centers Child & Adolescent Centers Charles E. Kubly FOCUS Center Nashotah Program OCD Center at Cedar Ridge Herrington Recovery Center Eating Disorder Center Advantages of ERP • Effective and robust. • “Only” side effect is increased anxiety during treatment (can manage by conducting graduated exposure). • Quick improvements (many after first week of treatment). Disadvantages of ERP • Hard work. • Noncompliance. • Absence of ERP. • Quality of ERP when available. Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Chad Wetterneck, PhD Clinical Supervisor and Cognitive Behavior Specialist Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Programs PTSD Program Locations: – – – – – Oconomowoc Milwaukee (West Allis) Brown Deer Regional Residential Trauma & Risk of PTSD • Epidemiology – 39% of adults have experienced a traumatic stressor • 25% of these later develop PTSD • Rape more likely to cause PTSD than injury or accident – Lifetime prevalence is 10% for women and 5% for men Common Reactions to Trauma • Fear and anxiety – – – – • • • • • • Re-experiencing the trauma Flashbacks Nightmares intrusive memories Trouble concentrating Hypervigilance (hyperarousal, over-alertness, startle) Irritability, “jumpiness,” anger Emotional numbing Dissociative symptoms Feeling like “going crazy” Common Reactions to Trauma • • • • • • • • • Avoidance (of trauma reminders; generalized avoidance) Feeling cut-off from others or isolated Feelings of a foreshortened future Guilt Shame Poor self image Loss of interests, depression Worthlessness/hopelessness Hopelessness/giving up/death ideas Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) • Most people recover from a trauma on their own • Some people continue to feel traumatized long after the event • When symptoms of trauma last more than 1 month, a person may be diagnosed with PTSD • When symptoms last a year, they are unlikely to get better on their own • Any change can be traumatizing When Professional Help is Needed • Trauma symptoms are getting worse or just not getting better • The traumatized person needs substances to cope with life • The traumatized person becomes depressed or suicidal Shame & Secrecy • Feelings of helplessness lead to shame • Shame leads to secrecy • Secrecy is BAD…. Why? – prevents “talking about it” (talking leads to natural healing) – prevents others from being supportive (leading to isolation) – prevents thinking about the trauma in new ways and emotional growth (processing) Treating the PTSD (1) Psychotherapists who specialize in PTSD suggest some general principles for the psychological treatment: 1. establishing a trusting therapeutic relationship, 2. providing education about the process of coping with trauma, 3. stress-management training, 4. encouraging the re-experience of the trauma, and 5. integrating the traumatic event into the individual’s experience. PTSD: Psychotherapy (CBT) • Stress Inoculation Training – Education about trauma – Anxiety management strategies (e.g., controlled breathing, cognitive restructuring) – Collaboratively select strategies and practice implementation • Cognitive Therapy – ID trauma-related beliefs linked to emotional and behavioral responses – Evaluate thoughts more logically – Determine if beliefs reflect reality, and if not, modify it Williams et al. (2012) PTSD: Psychotherapy (EMDR) • Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing – Generate images/thoughts about trauma – Evaluate aversive qualities – Alternative cognitive appraisal while person follows the therapists finger with eyes Williams et al. (2012) PTSD: Non-CBT Approaches • Psychodynamic therapy – Expressive therapy – Supportive therapy – Psychodynamic-integrative therapy Effectiveness: Needs empirical support • Group Therapies – Utility: (1) combat feelings of isolation (2) mutuality – Type • Supportive, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral • Overall goal: create a “safe” place Effectiveness: Needs empirical support (Williams et al., 2012) Why Exposure Based Treatments? • Exposure-based treatment approaches have been shown to be effective • Prolonged exposure has the most support in the research literature for the treatment of trauma – The traumatized person revisits the trauma in their imagination with a supportive counselor – The traumatized person stops avoiding Prolonged Exposure Can Prevent PTSD in Immediate Trauma Survivors Rothbaum et al. (2012) Factors Influencing Treatment Outcome • Pre-treatment variables = poorer outcomes – Trauma related • Hx of childhood trauma; Multiple traumas ; Personal vs. impersonal trauma; Time since trauma; Whether injured during trauma – Personal characteristic • Male gender; Suicidal; Living alone; Comorbid GAD/depression; Anger problems • General treatment variable = poorer outcomes – Low credibility of tx; low motivation of patient; low patient engagement; less completed homework (Williams et al., 2012) Breathing Retraining • The way we breathe affects the way we feel • Exhalation, not inhalation, is associated with relaxation • Slow down your breathing to avoid hyperventilation • Concentrate on slow exhalation while saying CALM (or RELAX) to yourself • Pause and count to 4 before taking second breath • The therapist makes a 3-minute recording of his/her voice leading the patient through the breathing exercise Rationale for the Treatment • The program focuses on addressing trauma related fears and symptoms. • Three main factors prolong post-trauma problems: – Avoidance of trauma related situations (e.g., sleeping with a light on, not going out alone) – Avoidance of trauma-related thoughts – The presence of dysfunctional cognition: “The world is extremely dangerous”, “I am extremely incompetent.” Rationale for the Treatment • The avoidance strategies prevent the patient from processing the trauma, from modifying the dysfunctional cognitions (e.g., trauma reminders are not dangerous). Rationale for the Treatment • The two main procedures are: – Imaginal exposure is repeated reliving of the traumatic event. Confrontation with painful experiences enhances the processing of these experiences and modifies dysfunctional cognitions. – In vivo exposure is repeatedly approaching trauma related situations that are avoided since the trauma. In vivo exposure is very effective in reducing excessive fear and unnecessary avoidance. It enables the patient to realize that these situations are not dangerous, thus modifying dysfunctional cognition. Factiliating Therapeutic Alliance • Praise patient for coming to treatment and acknowledge courage • Communicate understanding of the patient’s symptoms – Incorporate examples in treatment descriptions (e.g., common reactions) • Validate patient’s experience and be non-judgmental – May be the first time relating the trauma narrative, your reaction is important – Normalize and validate the response to trauma and what the patient did for “survival” after the event • Early behavioral responses to current dysfunctional schemas may have served an important purpose • Work collaboratively – incorporate the patient’s judgment regarding pace and targets of therapy Rationale for Imaginal Exposure: Revisiting the Trauma • Repeated revisiting: – Helps process (digest) the trauma, i.e., organize, make sense of it, “file it in the right drawer” – Results in habituation, so that the trauma can be remembered without intense, disruptive anxiety – Helps distinguishing between “thinking” about the trauma and actually “re-encountering” it. – Fosters the realization that engaging in the trauma memory does not result in loss of control or “going crazy” – Enhances sense of self control and personal competence Implementing Imaginal Exposure • Recall the memory as vividly as possible • Imagine that the trauma is happening now • Stay in touch with the feelings that the memory elicits • Describe the trauma in present tense • Recount as many details as you can • Include details of the event, thoughts, and feelings • Homework: – Listen to recordings of the imaginal exposure once a day and revisit the trauma Therapist-Patient Alliance During Revisiting • Express support and empathy with patient’s distress • Periodically reassure patient that he/she is safe (e.g., “I know this is tough; you are doing a good job staying with it”) • Titrate patient’s emotional response: – Probe for thoughts and feelings to encourage emotional engagement – If patient becomes overwhelmed with distress, conduct exposure with patient’s eyes open • Allow sufficient time after exposure to discuss and process experience and calm patient as needed Rationale for In Vivo Exposure • Trauma related fears are often unrealistic or excessive (e.g., going to a shopping mall). • Repeated in vivo exposure – Blocks negative reinforcement – Results in habituation, so that the target situation becomes increasingly less distressing – Fosters the realization that the avoided situation is quite safe – Disconfirms the belief that anxiety in the feared situation continues ‘forever’ – Enhanced sense of self control and personal competence Implementing In Vivo Exposure • Present the treatment rationale • Give daily life examples of in vivo exposure and habituation – (e.g., a child fearing being in a pool) • Develop a list of situations the patient has been avoiding since the trauma • Ask patient to rate the intensity of anxiety s/he experiences when imagining confronting each situation Implementing In Vivo Exposure • Arrange the situations in a hierarchy • If the patient cannot identify circumstance, suggest typically avoided situations. • Inquire about the actual safety of the situations Implementing In Vivo Exposure • Homework Assignment – Begin with assigning exposure to situations that evoke low to moderate levels of anxiety – Instruct the patient to remain in each situation for 30 to 45 minutes, or until the anxiety decreases considerably – Emphasize the importance of remaining in the situation until symptom level decreases by > 50% Example of an In Vivo Hierarchy Feared Situation SUDS Staying at home alone in the middle of the day 50 Driving to a friend’s home in a safe neighborhood in daytime 60 Driving to a friend’s home in a safe neighborhood after dark 70 Walking down a street in her parent’s neighborhood 75 Staying alone in her room on the campus with door locked 80 Walking with a friend on campus 85 Walking alone on campus during the daytime 90 Walking on campus at night 100 Addressing Avoidance • Validate patient’s fear and urges to avoid • Review the rationale for treatment • Avoidance reduces anxiety in the short term but in the long term it prevents learning • Memories are not dangerous • Use analogies to support the rationale • e.g., avoidance is like sitting on a fence, or living in a cave where the patient retreated to heal from the trauma Addressing Avoidance • Review the reasons that the patient sought treatment for PTSD • How do PTSD symptoms interfere with life satisfaction? • Review the progress that patient has already made • Provide a lot of support, encouragement • Schedule inter-session phone contact to provide support and discuss homework progress • Problem-solve solutions to concrete obstacles to compliance with therapy Facilitating Homework Compliance • Reiterate the rationale • patient must understand why she is being asked to do homework • Find out what is getting in the way: • Organization (e.g., lost sheet, forgot) • Practical issues (e.g., no time, no privacy) • Avoidance • Intervention guided by nature of the compliance problems The Solution to the Clinical Challenges of Effectively Addressing Addiction and Anxiety & Related Disorders: Integrated Clinical Services Knowledgeable/Competent Staff: • “Dually Licensed”, Ph.D. Supervisors • Board Certified Physicians (Psychiatry and Addiction Medicine) Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy The Herrington Recovery Center Rogers Behavioral Health – Tampa Bay 2002 N. Lois Avenue, Suite 400 | Tampa 813-498-6000 | rogersbh.org Thank you! 800-767-4411 rogershospital.org Michael M. Miller, MD, FASAM, FAPA mmiller@rogershospital.org