TT_CS_publisher - CLILingmesoftly

advertisement

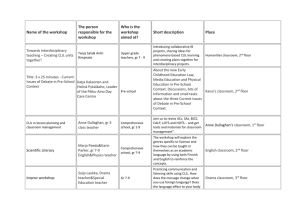

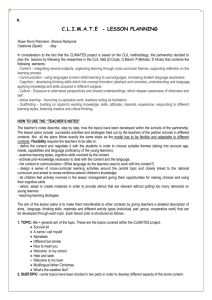

Abstract Classroom codeswitching in foreign language teaching is still a controversial issue whose status as a tool of both despair and desire continues to be hotly debated. As the teaching of CLIL is, by definition, concerned with the learning of a foreign language, one would expect the value of codeswitching to constitute an important part in CLIL research. This article sets out to argue that the use of the majority language in CLIL by teachers follows an educationally principled approach. It is expressed within an instructive and regulative register, motivated by behavioural, classroom and task management, and knowledge scaffolding considerations. Through a comparative data coding process using MAXQDA, several dimensions of codeswitching were identified and elaborated on. These dimensions included principledness, contextualisation, conflictuality, domain sensibility, linguistic deficit awareness, language learning and knowledge construction support, as well as affectivity. Taking this complex web as a reference point, the paper ends proposing six theses on codeswitching and recommending its relevance to CLIL teacher training. Keywords: CLIL, codeswitching, instructive register, regulative register, educational principles Introduction Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is a balanced approach for the learning of content and a foreign language. Its effectiveness and usefulness for both has been the subject of countless publications in the last several years (Breidbach & Viebrock, 2013; Dalton-Puffer & Smit, 2007; Lyster, 2008; Llinares, Morton & Whittaker, 2012; Nikula, Dalton-Puffer & Llinares, 2013). Although the learning of subject content is also marked by curricular and educational controversies within different national curricular requirements (Bosch & Gascon, 2006; Yerrick & Roth, 2005), the use of the foreign language and any other language as a vehicle for this input, as well as any pedagogical implications thereof, appears under-researched, and in dire need of principles (Dalton-Puffer, 2011). One major contentious issue can be traced to the foreign language's monolingual habitus in the learning of content (Lasagabaster, 2013). This appears to be grounded in the mainstream foreign language learning and research tradition which sees comprehensible input (Krashen & Terell, 1992), negotiation of meaning in the foreign language (Long & Doughty, 2011), and above all, the amount of exposure as paramount for promoting effective language learning in the classroom (Mitchell, 2011). Within these parameters only scant space is given to the learners' majority language, which is treated as a last-ditch tool for difficult and critical classroom situations and only to be used sparsely and judiciously 1(Richards & Rodgers, 2002). However, recent research within a cognitivist paradigm (Butzkamm & Caldwell, 2009; Cook , 2010; Macaro, 2014), and in particular in socio-cognitive and dynamic systems language learning approaches (Atkinson, 2011; Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008), is beginning to shed doubt on a mostly deficit role of the majority language in foreign language learning . A more radical stance towards a neatly compartmentalised monolingual approach in foreign language learning is taken by translanguaging and multilingual representatives which aim for the use of multiple languages to achieve the stated aims. In these approaches, the language practices of classroom participants are meant to confront and question linguistic inequality and increase participants’ multilingual symbolic capital (Garcia & Wei, 2014; Grenfell, 2011, Kramsch, 2009). “CLIL as a dual focused educational approach in which an additional language is used for the learning and teaching of both content and language" (Marsh, 2009, p. vii) has also been slowly but steadily on 1 When authors used the word mother tongue into was not changed into majority language. Otherwise majority language was preferred by the researcher to mother tongue. As a matter of fact there were often representatives of many different mother tongues present in the classrooms in this study. 1 the rise in Austrian classrooms. The legislative background for this was provided by the so-called "foreign language offensive”, which was started in the early 1990s by the Austrian Ministry of Education. Austria has a dual qualification system, in which every teacher is trained for at least two subjects which has led to a high level of flexibility in CLIL programs allowing individual schools to set up their tailor-made projects (Gierlinger, 2002). Working as a teacher, researcher, and teacher educator within this context I became increasingly intrigued by the complex roles and relationships between the languages involved in this learning environment. In particular, the apparently ambivalent role of codeswitching as a tool of help or hindrance caught my interest and led me to investigate into the following questions: 1. When does codeswitching in CLIL teacher talk occur and what is its role? 2. Is there a pedagogical orientation in teachers' codeswitching in CLIL? 3. Is codeswitching only carried out haphazardly and in an unprincipled manner? 4. Does codeswitching primarily operate as an emergency tool with a deficit habitus? The role of language in schooling As this article focuses on code switching and the specific roles of the teacher’s L1 for the process of learning in the CLIL classroom, a brief discussion of the relationship between language and content knowledge seems warranted. A rapidly growing number of educational linguists, psychologists, and didacticians are beginning to agree that the learning of subject matter language is intricately intertwined with the learning of its content. Therefore, content teaching practically always is language teaching, and school subjects are a system of discursive practices and genres (BeckerMrotzek, Schramm, Thürmann, & Vollmer, 2013; Christie & Martin, 2007; Gogolin, Lange, Michel, & Reich, 2013; Halliday & Matthiessen, 2013; Schleppegrell, 2004; Van Lier, 2004; Yerrick & Roth, 2005). It’s thus not possible, for instance, to do science using ordinary language, as learners need to become familiar with the comprehensiveness, depth and precision of scientific taxonomies relative to everyday taxonomies (Christie & Martin, 2007). Dealing with this intricate relationship between content and language is a methodological challenge and major teaching goal for all teachers (Hallet, 2013; Llinares & Whittaker, 2009; Martin, 2007; Scarcella, 2003; Vollmer & Thürmann, 2013, p. 44). As Gottlieb & Ernst-Slavit (2014, p. 83) put it, “students cannot engage in complex academic practices and accumulate deep content area knowledge if they do not have the linguistic tools for thinking, processing, participating, and, ultimately learning during content area instruction” 2. Arguably for CLIL, the choice and variety of scaffolding measures for mediating these linguistic tools in the CLIL classroom will be strongly influenced by three factors, firstly, the learner’s and teacher’s general and genre specific target language competence. Secondly, her subject specific didactic repertoire and thirdly, her metalinguistic and foreign language didactic repertoire. All of which will influence and guide a teacher’s codeswitching behaviour in the CLIL classroom. However, in the present study the data gathered showed that methodologically teachers only followed an immersive approach with minimal explicit foreign language interventions. As the focus of this naturalistic classroom research study (Gass, Schachter, & Mackey, 2011) was on the description and classification of teachers’ actual code switching behaviour, respectively their motivation for this, their, possibly theoretically desireable, foreign language intervention measures were not part of the scope and intention of this study. Use of the L1 in the L2 classroom The use of the majority language for codeswitching in the CLIL classroom cannot be appraised properly without giving attention to its role in the foreign language learning context. Since the advent of communicative language teaching and its present status of orthodoxy in mainstream language teaching, the use of the majority language in the foreign language classroom has proved controversial. Ellis & Shintani (2014) consider this to be due to the dominance of monolingual 2 I am very grateful to an anonymous reviewer who made me consider the role of codeswitching within the broader picture of the language of schooling more carefully. 2 teaching since the beginning of the 20th century. Turnbull & Dailey-O'Cain (2009: 206) notice that the theoretical and empirical support for exclusive target language use has led governments, language school administrators, teacher educators, publishing houses, and teachers to accept exclusive target language use in both second and foreign language learning and teaching as best practice which has reached, in their words, hegemonic practice. Butzkamm (2003: 29), for example, states that “at present the official guidelines in many countries recommend that lessons be planned to be as monolingual as possible drawing on the mother tongue only when difficulties arise”. Butzkamm & Caldwell (2009: 13) call it “the mother tongue taboo, which has been, without justification of any substance, the perceived didactical correctness for so many years and in so many countries". This is also reflected in the general literature on communicative language teaching, especially in a large number of published teacher guides, where, according to Ellis & Shintani (2014), language teaching activities are supposed to be carried out almost entirely in the target language. Following this, codeswitching is regarded by many teachers as a response to the undesirable constraints of the classroom that need to be overcome as quickly as possible, or at best, is to be used like a transit room on a journey to another country. Contrary to this mainstream perception, more and more SLA and FLL researchers identify the majority language as a vital resource, rather than a liability, in the learning of any other language (Butzkamm & Caldwell, 2009; Cook, 2010; Macaro, 2014; Saville-Troike, 2006; Turnbull & DaileyO'Cain, 2009). Ellis & Shintani (2014, p. 233) note that “in recent years, advocacy of L1 use has grown in strength and it is now clear that the pendulum has swung firmly in its favour at least in applied linguistics” This has lead educational linguists, noteably Macaro (2014), to call for a pedagogy of codeswitching based on a theory of optimal L1 use for foreign language learning. He posits that the question of whether the first language (L1) should be used in the oral interaction or the written materials of second or foreign language (L2) classrooms is probably the most fundamental question facing second language acquisition (SLA) researchers, language teachers and policymakers in this second decade of the 21st century. (p. 10) Increasing scholarly interest in this area has also resulted in a number of studies (Levine, 2011) trying to shed light on the functional purposes of teachers’ L1 use in the classroom. The functions identified for teachers’ codeswitching in several studies show remarkable similarities which, following systemic functional linguistics, can be attributed to a regulative or an instructive register (Christie, 2002; Llinares & Whittaker, 2009). The former being the discourse to allow teachers and students to manage and organise the classroom’s social world, the latter being the classroom talk through which the academic content and skills being learnt are communicated. When splitting writers’ lists of functions for codeswitching into three broad categories, a small number of “trigger situations” can be noticed. Category one, behaviour management, typically includes the building of rapport with a special emphasis on decreasing language anxiety (MacIntyre & Gregersen, 2012), and maintaining discipline in the classroom. Category two, classroom and task management, features highly in any administrative classroom talk and (mostly) complex task instructions. Category three, concept management-which refers to the actual learning taking placelists predominantly comprehension problems, grammar instruction, and time-saving issues. The obvious prevalence of foreign language teachers to use the majority language in particular contexts leads Levine (2011) to maintain that the majority language needs to be reappraised as the unmarked code or default choice for several key contexts in the classroom. Nevertheless, Ellis & Shintani (2014: 233) sound a note of warning on the prevailing controversy by stating, “the arguments, it should be noted, are for the most part theoretical in nature, representing opinion and belief, rather than empirically based findings. It is for this reason that the whole issue of the use of the L1 has become 3 so contentious”. For them, the central question SLA researchers should ask is, “whether L1 use in the classroom facilitates L2 acquisition”. CLIL and codeswitching Taking this discussion into the CLIL classroom, three specifics need to be considered. Firstly, CLIL thrives on its diversity and contextuality (Perez-Canado, 2011). For example, Coyle (2007) lists more than 200 different types of CLIL programs based on such variables as compulsory status, intensity, age of onset, starting linguistic level, or duration. Recently, however, an increasing number of CLIL researchers have tried to systematise and theorise this disparate, mostly grassroots, and highly atheoretical phenomenon by establishing more general CLIL practices and principles, (Dalton-Puffer, 2011; De Graaf, Koopman, Anikina, & Westhof, 2007; Georgiou, 2012; Mehisto, Frigols , & Marsh, 2008). Secondly, CLIL lessons are, by their very nature, subject-content driven learning environments (Dalton-Puffer, 2011). This inevitably has an effect on teachers’ habitus, self-perception and identity, language choice, and methodology. Thirdly, the use of the majority language – and in more progressive contexts (Canagarajah, 2013; Garcia & Wei, 2014), the use of all language resources – as a methodological resource tool - has always formed part of a general CLIL philosophy by its main representatives. There may be some variation in the actual amount of L1 implementation, for example, some theoreticians consider twenty-five percent to be appropriate, but most agree on the non-target language’s legitimate space in the CLIL classroom (Costa & D'Angelo, 2011; Coyle, Hood , & Marsh, 2010; Dalton-Puffer, 2011). However, there seems to be far less agreement about the actual methodological mediation and ownership of this space. Given this complex web, CLIL teachers’ codeswitching beliefs and practices would suggest an important field of study. However, contrary to this, the number of studies addressing CLIL teachers’ codeswitching use are thin on the ground and mostly difficult to compare (Coonan, 2007; Costa, 2011; Grandinetti, Langellotti, & Ting, 2013; Hüttner, Dalton-Puffer, & Smit, 2013; Lasagabaster, 2013; Llinares & Whittaker, 2009; Mendez Garcia & Pavon Vazquez, 2012; Nikula, 2010; Wannagat, 2007; Viebrock, 2012). An overview reveals the following features. Firstly, the majority of the studies base teachers’ beliefs on codeswitching on qualitative interviews or questionnaires without any reference to classroom data, and therefore may run the risk of presenting a perspective whose results do not adequately portray the complexity of the classroom codeswitching context (Hüttner & Dalton-Puffer, 2013; Lasagabaster, 2013; Mendez Garcia & Pavon Vazquez, 2012; Viebrock, 2012). Secondly, some studies, although based on a mixed-method approach, investigate teachers’ language without making their codeswitching a major issue (Nikula, 2010). Thirdly, others - although providing a considerable amount of codeswitching incidents - decline any deeper or systematic significance to this phenomenon (Grandinetti, Langellotti, & Ting, 2013). In table 1, the two studies that deal explicitly with the functions of teachers’ codeswitching in CLIL present the following categories which are focused through the instructive and regulative classroom registers. 4 Table 1: Functions of teacher L1 use in the CLIL classroom Register Lasagabaster Mendez Garcia (2013) & Pavon Vazquez, (2012) Instructive To help students’ To help understanding students understand complex ideas and notions Instructive To make L1 and L2 To make cross comparisons linguistic comparisons Regulative To boost debate To stimulate the learning of both language and content Regulative To feel comfortable To tell in the CLIL class anecdotes Regulative To deal with To use routine disciplinary issues language Although Lasagabaster (2013:17) concludes that CLIL teachers’ codeswitching is implemented with little systematic reflection on teachers’ everyday practices, the overall similarity of characteristics in teachers’ codeswitching in CLIL already suggests that this may be more than just a haphazard and incidental phenomenon. Context and design of the study This longitudinal qualitative study, which was carried out in school year 2011-2013 tried to investigate into CLIL teachers' codeswitching behaviour. Data was gathered through naturalistic classroom research (Gass, Schachter, & Mackey, 2011) from four non-selective lower secondary comprehensive school classes (14- to 15-year olds) and one selective3 (16- to 17-year olds ) upper secondary grammar school class, where CLIL was taught in modular projects. The projects were selected on a highly individualistic and experiential level. Nevertheless, they followed certain criteria such as internationality versus local contexts, the availability of appropriate materials or cognitive complexity. The subjects covered were chemistry, geography (twice), history and psychology (upper secondary level). The lesson durations were bi-weekly, with each lesson lasting fifty minutes. And, unlike in other European countries, there were no regulations or recommendations for the amount of time to be used in the target language. While the majority language was German, pupils’ mother tongues included, apart from German, Albanian, Arabic, Mandarin Chinese, Romanian, Serbo-CroatBosnian (SCB), Tagalog, and Turkish. Initially, classes were selected for the same age range and a nonelitist approach towards CLIL, but for practicality and data richness purposes, a more elitist and slightly older class was added. Now consider table 2, which displays teachers’ professional profiles: 3 Austria has a two tiered educational system where students at the age of 10 are (self) selected into a more academically focused branch (grammar school) and a more vocationally focused branch (comprehensive schools). This selection process is mostly affected by learners' marks in primary education. 5 Table 2: Teachers’ professional profiles Teachers Profile Dimensions T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 Age 42 30 48 41 40 Teaching experience 16 years 3 years 26 years 20 years 15 years QTS (Qualified Teacher Status) • • CEFR levels C2 C1 B1+ C2 B2/C1 Previous CLIL experience CLIL training 15 - years 2 - years None 8 - years None None None None European CLIL course 2012 University CLILCourse 6 English Philosophy Psychology • English Geography • • Physical sciences: Physics, Chemistry Mathematics Geometrical Arts English Geography History German These profiles can be summed up in the following way: All of the teachers, except for one, were very experienced subject teachers, and were highly recommended by their principals for their teaching excellence. Three of them were also English language specialists with a considerable amount of CLIL experience, whereas the two subject specialists only had just started with CLIL. None of them had undergone any lengthier CLIL training. Apart from T1, all of the teachers taught in non-selective comprehensive schools, spanning an age range from 10 to 15 years. T1 taught in a so-called grammar school (AHS) with an age range from 10- to 18-years old. Their target language competence was not determined through any official assessments but rated on a bona fide basis by the author with respect to the classroom observations and their language learning background. Research methodology The study employed a combination of semi-structured interviews (Burns & Barnard, 2012), classroom observations, and stimulated recall reflections. The interviews took place in an open-ended manner in a non-evaluative environment. Some interviews were carried out immediately after the observed teacher had left the classroom, which usually forced me to rely on my field notes and memory of lesson episodes. Some interviews were stimulated by already available transcripts of the lessons or by questions focused on video sequences. The classroom observation data was gained by filming the teachers, focusing on their codeswitching. All in all, 864 minutes of semi-structured interviews, 1245 min of video observations, adding up to 2109 minutes of recorded data were transcribed and evaluated (table 3). Table 3: Transcribed data in minutes Dimensions Interviews CRO Sum T1 65 45 110 T2 111 254 365 T3 252 396/39 648 T4 126 165/81 291 T5 310 385 695 Sum 864 1245 2109 Note: T1-5: Teachers; CRO - classroom observation data This data was qualitatively analysed by using MAXQDA4. The coding system in MAXQDA was partly pre-defined by previous research, my research questions, but also emerging, following Corbin & Strauss’s (2008) analytical tools for doing grounded research through several comparative data sessions and theoretical samplings. In this process of constant comparison and revision, a state of theoretical saturation (Corbin & Strauss, 2008: 263) was achieved which allowed a confident evaluation of the questions and hypotheses raised for this study. In the classroom data any incident where teachers switched from the target language English into their mother tongue AustrianGerman was coded and categorised in MAXQDA. Categorising the data Taking the regulative and instructive registers as major guiding lines for the typical pedagogic discourse in the classroom (Christie, 2002) the following categories appeared to be explanatory enough to allow a satisfactory qualitative interpretation of the research data. The regulative codeswitching data was split into: 1. Classroom and task management codeswitching: CTM. This was defined as any majority language intervention by the teacher that supported the setting up of the learning environment. It specifically included: giving instructions, making announcements, opening and closing lessons, regulating floor taking, homework reminders, passing out hand outs, etc. 4 MAXQDA is a professional software for qualitative and mixed methods data analysis, www.maxqda.com 7 2. Behaviour management codeswitching: BM. This comprised any majority language intervention by the teacher for interpersonal and rapport-building purposes. Typical examples included: checking on pupils’ behaviour, telling jokes, anecdotes or any other (language) anxiety reducing measure, encouraging remarks, etc. Instructive classroom codeswitching following Llinares, Morton, & Whittaker (2012) and Nikula, Dalton-Puffer, & Llinares (2013) was broken down into three major categories: 1. Content focused codeswitching: CF. This category represented any codeswitching by teachers to ensure the conceptual understanding and development of subject knowledge. 2. Word focused codeswitching: WF. This was understood as a bridging category between language learning and conceptual development. Typical examples included teachers’ quick translation of any expected lexical problem. 3. Deficit focused codeswitching: DF. This category represented any codeswitching by teachers that dealt with their linguistic shortcomings. Typical examples included the teacher’s acknowledgement of her ignorance preceded by utterances such as “I don’t know the English word for Dreibein (tripod)” and/or by body language and hesitation markers that indicated a (linguistic) problem. In the same vein, any comment in teachers’ reflections pertaining to the categories above was coded accordingly. Discussion 1: Codeswitching for regulative purposes Teachers’ classroom codeswitching for regulative purposes fell between two broad categories either dealing with classroom and task management or with behaviour management. A statistical breakdown of all the incidences in the classroom coded for regulative codeswitching showed that classroom and task management (CTM) covered about 61 % of the incidences, whereas behaviour management (BM) codeswitching was coded in 39% of all the occurrences. Since the number of classes observed with respect to the individual teachers varied considerably, any codeswitching comparison between teachers was restricted to teachers T3 and T5 whose number of lessons observed was almost the same (see table 3). With these two teachers, the amount of CTM codings varied considerably. For example, T5 initiated more than eight times the number of classroom and task management incidents than T3 (65/08). On the other hand, regarding behavioural management incidents, both teachers showed almost exactly the same number of codeswitching occurrences (23/22). Their length and complexity, however, differed considerably from short single turns to multiple exchanges involving several participants (extract 1). Furthermore, there was wide variation concerning the other teachers, as hardly any regulative codeswitching incidents appeared in their data. Nevertheless, a clean separation between classroom and task management (CTM), and behaviour management (BM) appeared to be difficult on various occasions, as these two codings were often closely intertwined. For example, a teacher’s instruction was followed by a behavioural remark, continued by further instructions, followed by another behavioural remark and concluded by the final instructions. It is possible for the entire exchange to take place in one target language piece or to be broken up in L2 – L1 – L2 framing patterns. The following exchange in which the teacher introduced an internet quiz, is representative of this discourse pattern5. 5 The translations of the codeswitchings tried to stay as closely to the original as possible and were done by the author and put in square brackets [translation]. For better readability the whole exchanges were italicised and 8 Extract 1: T5: okay, and at the bottom of this page you have got a different kind of quiz, (…), first of all, you have just to listen, you don't have to do anything you, okay P1: du musst klicken! [you have to click on it] T: könnt ihr bitte auf, könnt ihr bitte zuhören, ihr braucht, ihr braucht jetzt nichts tun, ok ihr braucht nichts tun, ihr braucht nur zuhören, [can you stop this, you don’t need to do anything, just listen] P2: (ui) T: das ist halt nicht besonders intelligent, gelt, das stört mich, und dann entscheidet ihr euch für einen Kandidaten [that’s not very intelligent, I don’t like this, and then you go for a candidate] P3: Obama T: was weiss ich, [whatever] P4: Romney T: und dann gibt es die Fragen und dann muss man immer [and then there are questions, and then you have to] and here you have to, to decide which answer is right, and if your answer is right your candidate will do a step in front of you, okay, so I would say try this quiz it's quite useful Classroom and task management codeswitching Classroom and task management codeswitching was used for general administrative announcements: opening and closing lesson turns, issuing homework, regulating floor taking, giving instructions for carrying out an activity, or for the use of technical tools and seating or learning arrangements. As mentioned above, it was often placed in a framing or sandwich pattern (L2 – L1 – L2). However, sometimes there were also appeals by students to the teacher for CTM. Notice how in extract 2, the teacher begins in English, only to be interrupted by a student’s request for German, which he acknowledges by immediately switching to the L1. Extract 2: T3: listen to me please, I give you some explanations, what you do in the first time is, choose, (…) P: können sie das auf Deutsch sagen? [can you say this in German?] T: wir haben sechs Materialien her außen die wir erst besprochen haben, (…) [we have six materials here that we talked about,] (…) Whilst clarifying regulative issues appeared to be the primary motive for codeswitching in these instances, many of them may have served the purpose of supporting students’ implicit language learning. Notice how in extract 3, the instructional remark “work alone” was not only emphasised by repeating the keyword “important” three times and using a near-synonym “very necessary”, but also that its translation “wichtig” was provided. Almost all of teacher 3’s and roughly 50% of teacher 5’s CTM codeswitching extracts exhibited characteristics of repetition, attention, slower rate of delivery, paraphrasing, all of which may help acquiring new words (Lightbown & Spada, 2006). Extract 3: the codeswitchings printed in bold. Seemingly redundant remarks such as repetitions, hesitation markers, digressions, etc. were deleted from the quotes which is indicated by three dots in round brackets (…). 9 T3: (…) so it is, stop it is very necessary that you work alone, wichtig, important, it's important, it's very important to work alone now for three minutes This analysis of teachers’ classroom data raised the question for the reasons that teachers gave in their reflective comments for codeswitching in CTM situations. T1 and T4, the most “foreign language” competent teachers, agreed on using the L1 only on rare occasions of problematic cases of incomprehension. This concurs fittingly with a zero occurrence of CTM codeswitching in their data, which is however far smaller than T3/5’s sample. Notwithstanding any likely language problem, T3/5 did not attribute their higher use of codeswitching to any linguistic deficits, but, instead, articulated other specific reasons for their behaviour. Both mentioned time pressure and technical classroom aspects, such as problems with the computer or projector, being a primary driving force for their codeswitching. Furthermore, T3 mentioned subject-specific reasons related to chemical experiments. This included the involvement of hazardous materials and very specific tools (labelled in the L1) for which he had to ensure that instructions were clearly understood and followed. However, contrary to teachers’ general supportive behaviour for language learning in their reflections, this was not mentioned as an explicit motive for any CTM codeswitching. The general picture emerging from the CTM codeswitching data shows the following features: A high variability of codeswitching within the teachers was noticeable. For example, while three teachers didn’t display any codeswitching at all, the two non-language specialists initiated 100% of the incidents, with T5 being involved in about 90% of the codeswitching extracts. Despite the actual differences in the classroom data, all teachers emphasised in their reflections to use codeswitching if classroom management language or instructions in the target language were considered to be “problematic, difficult, personal, time-consuming, or not absolutely watertight and fool proof in potentially hazardous situations”. The codeswitching was typically wrapped into an L2 – L1 – L2 sandwich pattern that appeared to have potential for language learning. Behaviour management codeswitching This chapter will investigate into the second major regulative register, behaviour management. Behaviour management codeswitching was used for incidents considered by the teachers to be disruptive to the on-going teaching and learning process. Eventually, it was meant to lead to creating a positive learning environment. BM was always teacher-initiated, had a tendency to show highly emotive features through increased voice and higher pitch level, expressive body language, and even when focused on a single student, was usually addressed to the whole class. Very often it was introduced in the target language but quickly repeated with stronger discursive force in the majority language and followed by the target language when the “issue” seemed to have been successfully settled. Extract 4 is a typical example where the teacher (after a series of disruptions by this student) finally decides to send him to the head person. Extract 4: T3: please we have to stop our experiments, sit down everybody, (…) P: (student mockingly) sit down please T: und wenn ich dich jetzt nochmals ermahnen muss dann werde ich dafür sorgen, dass du hinausgehst, draußen kannst du (ui) ok? [if I have to reprimand you again I’ll take care that you leave the classroom, outside you can (ui) ok?] please stop talking now, listen to me (…) (points at student) go to the headmaster and tell him what you have done 10 Teachers reported choosing the L1 on purpose for reasons of authenticity and forcefulness. In their comments they emphasised that using the L1 for disciplinary purposes was “more energetic and expressive” (T4), whereas using the TL was not “authentic or somewhat artificial” (T5). This appeared to be a sentiment voiced by all teachers in their reflective comments. Furthermore, notice the apparent cognitive overload in extract 5 where the teacher’s complaint of being unable to concentrate because of students’ constant chatting lead to codeswitching. This was expressed in a high pitched voice through a very strong colloquial expression “die Quatscherei, die geht mir auf den Keks” that definitely left the register of the usual scholarly detachment and showed the teacher’s “raw” feelings at this moment. Extract 5: T3: so stop, nein, das ist mir jetzt extrem wichtig und da will ich dass alle zuhören und die Quatscherei da, die geht mir auf den Keks, ja die ganze Zeit, ich kann mich nicht konzentrieren weil weil ich da immer den Lärm hinter mir habe, “ [stop, no, that is extremely important for me and I want you all to listen, and all that chatting is getting on my nerves, yes the whole time, I can't concentrate because there is always this noise behind me] Also note how in extract 6, the teacher, probably because of a certain affective overload, was suddenly lost for words. Extract 6: "(Teacher turns towards a chatty group of boys) and you are too loud for me and I will get very angry now (raises his voice considerably) and will stop everything, I'm not interested in being angry and, and (.) (.) have to (.) (.) I don't know the words, ich glaube nicht dass du so mit deiner Gruppe arbeiten kannst und das bringt vor allem nichts, (T3). [I don't think that you will be able to work like this with your group and it is of no use] This linguistic-affective tension was addressed repeatedly in teachers` reflective comments, such as the following: “the more disruptive the students are, the more L1 is used by me” (T5), “for behavioural problems I even use the dialect” (T4), “I can’ take that much disruption in CLIL, it is wearing me out” (T3) . Apparently, behaviour management in the classroom and teachers’ codeswitching were strongly guided on the one hand by an explicit cognitive choice about the mother tongue’s stronger authoritative and authentic force (see also extract 1). On the other hand, it was also guided by the speaker’s affective irritation which makes her realise the difficulty of expressing anger in the foreign language and her lack of anger repertoire and fluency. This concurs fully with research on bilingual anger management where speakers’ L1 turned out to be the preferred language for expressions of anger (Dewaele, 2006, p. 146). Summing up, the highly variable and unforeseeable nature of regulative aspects in classrooms poses a considerable strain on foreign language teachers’ communicative competence (Swain & Lapkin, 2013). This paired with an intuitive assessment of a lack of linguistic authenticity, especially in emotionally charged behavioural situations, makes them consciously opt for the majority language. This powerful guiding principle of linguistic appropriateness is however typically changed as soon as the trigger situation is over and it is often linguistically softened through an L2-L1-L2 sandwich pattern. However, the data does not indicate any evidence as to whether this understanding of a linguistically inappropriate use of the majority language for social and regulative purposes is only a CLIL phenomenon or can be observed in the EFL classroom as well. 11 Discussion 2: Codeswitching for instructive purposes Teachers‘ codeswitching for instructive purposes was divided into three categories (table 4). The first category, concept focused codeswitching (CF), denotes teachers’ explicit and mostly lengthier efforts to ensure an understanding of the subject content through codeswitching. Category two, word focused codeswitching (WF), while on the surface motivated by conceptual understanding, can arguably be considered an intermediary between content comprehension and language learning. Its frequency of occurrence, consistent formal structure, and potential for language learning seem to justify an extra category. The third category (DF) deals with teachers’ perceptions of and reactions to their own linguistic deficits in the CLIL classroom, as triggered by instructive incidents. Table 4 shows a simple statistical breakdown of all the incidences coded for instructive codeswitching Table 4: Instructive codeswitching in the classroom observation data. Register Coding Number of Percentage occurrences 38 46 32 39 12 15 Instructive Concept focused codeswitching: CF Instructive Word focused codeswitching: WF Instructive Language deficit focused codeswitching: DF Concept focused codeswitching A closer look at the subcategories for the instructive register revealed two recurring patterns. The first type was a sequence of: (1) teacher explanation in L2 > (2) comprehension problem noticed6 > (3) re-explanation of content matter in L1 > (4) continuation of content matter in L2. Type II showed the same order but after stage 2 reasons for the necessity of codeswitching were given. Typical statements were: “that’s relatively difficult, so I’ll do it quickly in German (T5); okay, briefly in German so that everyone will have understood it (T3); Okay, now again, maybe for everybody (T3)”. Sometimes comprehension and clarification checks such as "do you understand my English or shall I do it in German?; What does X mean?; Can you explain how that works? " were used as a trigger point for codeswitching. These turns might just cover the clarification of one word or extend into lengthier conceptual clarifications. Extract 8 and 9 illustrate this codeswitching behaviour. Extract 8: T5: (…) and this, well this, this is the convention (ahm) (points at projector screen), (.) (.) what's the atmosphere there? Wie wirkt denn das auf euch so eine Convention? [How does such a convention appear to you?] Extract 9: T3: (…) 35 g fat, so we have, we have lost something, because I didn't do it in a very good way but with 26% we are already near the reality (.) (.) good, kurz auf Deutsch damit wir das auch verstanden haben [briefly in German so that we (sic) have understood it], (goes on explaining the problem in German), and the same we do with olives ok, less heat because otherwise I would destroy the good things Teachers used codeswitching for instructive purposes in a decidedly purposeful way also supported by their reflective comments on this issue. Firstly, teachers constantly monitored the complexity of the comprehension process and acted accordingly. For example, all teachers pointed out an individual threshold for codeswitching with respect to comprehension problems. While this appeared to be lower or higher, grounded in the teacher’s overall teaching and learning belief system, they 6 See extract 10 and 11 12 maintained that their “pedagogical feeling” was based, among others, on a close observation of their students’ body language and linguistic responses, which made them codeswitch or allow their students to codeswitch (extract 11). Extracts 10 – 11 are representative of this conscious monitoring. Extract 10: T3: yes it‘s about my pedagogical feeling when I look at students’ faces, Extract 11: T1: yes, I may codeswitch for comprehension or safety purposes but what also happens is that somebody persistently sticks to German and that‘s okay and I’ll talk back in English and that‘s the way it is Furthermore, teachers repeatedly pointed out that their codeswitching behaviour was affected by their knowledge of students’ language competence, such as “with S. and P. I always stick to English” (T5) or “with E. I will codeswitch because his English is really low and it is already a challenge for him to actually write the words in English” (T1). Basically, all teachers voiced an overarching commitment towards subject content knowledge. Then, if that was felt to be at risk, foreign language learning issues played a subordinate role. Even the language specialists felt very strongly about their content subject role and viewed themselves in CLIL primarily as subject teachers. Notice in extract 12 the teacher’s straightforward response when being asked about her role in the CLIL classroom. Extract 12: "R: so what are you in CLIL, an EFL teacher or a philosphy and psychology (PuP) teacher? T1: a PuP teacher”. (R = researcher) Summing up, the data clearly indicates that teachers carefully and deliberately chose and fine-tuned their codeswitching for instructive purposes. The major critical points of departure for this behaviour were: 1. Cognitive complexity of the input and content supremacy: Teachers either anticipated potential incomprehension for cognitively complex content or monitored students’ responses as perceived through explicit or implicit non-comprehension markers (for example, body language) and decided to clarify the problem through codeswitching. 2. An appreciation of students’ individual language competence: Teachers used codeswitching as an individualised scaffolding measure; 3. Time pressure: Teachers used codeswitching to speed up knowledge mediating processes; Word focused codeswitching Teachers used word focused codeswitching quite frequently (39%) as a quick comprehension check based on a comparison of the lexical representations. Any utterance that followed the structure “Y in German is called/means Z” or “Y is Z” or “It’s Z”, whereby Y stands for the target language word and Z for its translation, was counted as an exemplar of this category. Another typical patterns was: (1) teacher mentions keyword > (2) teacher makes quick comprehension check (“clear about the word?; Do you know Y?; Have you ever heard this expression?”) > (3) teacher provides translation equivalent. Furthermore, the codeswitching often appears in mid-utterances as a quick L1 translation check. Extract 13 is a typical example of this technique. Extract 13: 13 T5: so how do you call these elections at the beginning of the campaign? Campaign means Wahlkampf ja, how'd you call it? However, what started off as a quick checkup frequently led into conceptual clarifications through concept focused codeswitching or explanations in the target language. Extract 14 exemplifies this. Extract 14: T5: (…) the candidate was very, very conservative , what does it mean conservative? It is quite similar to the German expression, ja, what does it mean for you? P: keine Ahnung [no idea] T: was heisst denn konservativ auf deutsch? [What‘s conservative in German?] (Followed by various turns in which the teacher tries to elicit and explain the meaning of conservative in German) Extract 13 suggests that the learner does not have any serious conceptual problems, as the German translation is not followed up by the teacher. On the surface, its main purpose appears to be a quick clarification check with probably also strengthening the formal linguistic mapping between the two lexical representations. Although some teachers, for example, advocated a biliterate approach in which learners should also know the lexical representation of the majority language, especially with respect to subject specific vocabulary, this never surfaced as a lengthier and preplanned task. In extract 14, however, the quick translation check ran into immediate conceptual problems as the learners apparently did not know the meaning of the lexical representations in their L1 either (note also the discussion on “the language of schooling”). Generally speaking, it appears that any neat separation between codeswitching with a content focus and codeswitching with a language focus runs the risk of oversimplifying the complex relationship between content and language learning in CLIL. For example, the strategy of clarifying expected lexical problems through an immediate translation is hard to be justified as either being exclusively motivated by purely conceptual or linguistic reasons. In other words, do teachers provide a translation because they think referring to the German word may enhance a conceptual understanding of the content or because this might support the learning of the target language code? The inherent connectedness of language and content (Nikula, Dalton-Puffer, & Llinares, 2013) poses a tricky problem when using codeswitching as an explanatory construct for either language learning or conceptual development in CLIL. This becomes also evident when looking into predictions made by the Revised Hierarchical Model (Tokowicz, 2013) which maintains that L2 words are strongly connected to their L1 translations, because the L2 initially relies on L1 for access to meaning. Following this line of argument, it appears justified to interpret the juxtaposition of L2 and L1 linguistic forms as a category of codeswitching in its own right, that appears to focus on the surface on content comprehension and conceptual strengthening, but may implicitely also further the lexical acquisition of the target language word. Summing up, this codeswitching checkup played an important feedback role for the teacher in assuring the understanding of subject content. Furthermore, this classroom data is thin on the ground with respect to any explicit language work. As mentioned earlier, teachers voiced an implicit and immersive attitude towards language learning in their CLIL classes which resulted in an almost unanimous rejection of doing deliberate vocabulary work. T1 sums up the general attitude towards more language focused codeswitching, “of course they have to learn technical terms but that is not any focused vocabulary work, it is just the German translation so that one knows it when one needs it”. 14 Language deficit focused codeswitching The third area for teachers’ instructive codeswitching dealt with their own linguistic shortcomings. These incidents were typically preceded by various hesitation markers, short pauses, an "I do not know this" body language, and/or even open appeals for help. As this pattern exclusively appeared in the non-linguist specialist classroom, it was often preceded or followed by remarks emphasising the teacher's status as a "non-language teacher". However, to show the complexity and discourse potential of these incidents, let’s take a closer look at a more extended example. Extract 15: T3: yes and this is what we have in the lab usually a filter, (ahm) and some (ahm), (ahm), (ahm), (.) (shows a funnel, body language shows uncertainty) S: Trichter [funnel] T: Trichter, [funnel] and what we have to do with the round filter is to (.) (folds it) P: knick [fold] it PP: knicking [folding] T: knicking, [folding] thank you for the word, I do not know if it's right but it sounds good S: it's fold SS: knicking S: you fold it T: I fold it S: knicking (laughter) T: many times and then I can make it for our Trichter, [funnel] shall we try to find the word (walks over to his laptop) I have opened my dictionary, what's the word for Trichter, (types it into his laptop), and ahm (.) funnel, it's the word funnel, it's for me (writes it down on the board), (14:40 16:10) In this incident, the teacher started by eliciting from students a lab procedure which involved separating and purifying mixed substances such as dirty and salty water. While trying to set up this procedure, various hesitation markers, short pauses, and an obvious "I don't know" body language, accompanied by showing the object to the students, clearly indicated a language problem which prompted a student to provide the L1 word "Trichter”. The teacher picked it up without any comment or hesitation and continued presenting and describing what he needed to do with it. While folding the paper, he signaled again visually and linguistically (but without codeswitching) a problem with the desired word "fold/bend". This prompted a student to use the compensatory strategy of foreignising to provide him with the word "knick” which originates from the Germanic word "knicken” (bend). This was immediately taken up by other learners and also by the teacher, even though, another student voiced her doubts by suggesting the correct word "fold". This was then repeated and accepted by the teacher who continued his demonstration, and who also quickly became aware that his first problem of the naming of the object had not yet been solved. Although he still codeswitched and mentioned the German word, he simultaneously provided a successful language learning model by using his laptop to look up the word in an Internet dictionary (www.leo.org). The students could follow this, as his computer was linked to the overhead projector. He then decided to make this term even more salient by repeating it, writing it on the board, and telling them to look for it in their handouts. The turns overlapped throughout this learning conversation and it did not take longer than 90 seconds. The whole episode has been presented and described in more detail as it is believed to be representative of the rich and joint learning potential of codeswitching in CLIL in which the teacher was the subject knowledge facilitator while concurrently acting as a foreign language learning model. 15 A similar pattern showed the teachers’ struggle for a target expression, which was indicated by pauses and repeated hesitation markers, as shown above. The codeswitching was initiated by the student’s “generous offer”. Extract 16: T3: (…) there exists another bad story because you know India, in India its ah ah ah (.) (.) (.) S: sie können es auf Deutsch sagen wenn sie wollen [you can speak German if you like] T: ja I know, in Indien ist es üblich wenn ein Mädchen verheiratet wird (…) [In India it is common when a girl gets married] Although the data analysis does not allow any hard or empirical conclusions regarding the intake efficiency of these incidents, the videos show high energy arousal and attention (the number of participants involved, their body language, and intensity of exchanges) as well as a high repetition of the target word. Since these are considered strong enabling conditions for learning, and the learning of words in particular (Ellis, 2013; Laufer, 2013; Laufer & Nation, 2012; MacIntyre & Gregersen, 2012) incidents like this may actually represent rich learning opportunities that also allow for a more democratic learning climate in CLIL as compared to both the foreign language and regular subject classroom. All in all, these cooperative learning incidents triggered by codeswitching were relatively rare, only occurred in the non-language specialist data, and were almost exclusively initiated by one teacher. Furthermore, while the classroom observation examples do not show any openly expressed examples of linguistic shortcomings by the teachers, their reflections reveal a far less confident picture. For example, all teachers addressed the deficit metaphor "I’m not a native speaker". This was expressed by stating that one’s L2 use may be "different" (T1), deviating from native speaker norms, even resulting in "gobbledygook" (T5). This inevitably resulted in more intensive cognitive processing. Such examples include "I struggle for words or the right/most appropriate expression" (T3) and “it was more exhausting and takes up more energy” (T3). T1, the almost bilingual teacher, while pointing out that her English was very good, nevertheless added “and yet I know that I don’t know anything because I’m not a native speaker and there are certainly situations where I use the language differently from our native speakers”. Notwithstanding this general deficit attitude, the teachers expressed differing beliefs towards the use of codeswitching as a compensatory measure for any of their own linguistic uncertainties. While T1 flatly rejected this as a guiding principle, T3, arrived at a completely different conclusion as the following quote shows: “I’m getting a lot more confident in doing codeswitching, I have realised that because of some of my language deficits I cannot present every content in the way I’d like to do this as a content subject teacher, and therefore whenever I have the feeling I cannot get to the heart of it, then I codeswitch, and yes I feel very fine about it”. Given the apparent potential of codeswitching as a joint learning experience and as an anxiety avoidance initiative, as shown above, and the dearth of truly bilingual CLIL teachers, this deficit attitude appears a deplorable and deeply counter-productive attitude which should be critically appraised in CLIL teacher education courses. Conclusion Codeswitching in CLIL, following similar discussions in the foreign language classroom, has suffered from a bad reputation by language learning approaches that focus on communicative competence 16 through input, negotiation for meaning, and output production. Loewen (2014: 46) outlines the codeswitching problem in a forceful and straightforward way, “when the L1 is used, learners do not receive L2 input; furthermore, there may be no negotiation of meaning, nor are learners pushed to produce L2 output”. Contrary to this position the classroom observation and reflective data of this study revealed a clear potential of codeswitching as a pedagogical and learning support tool. The CLIL teachers in this study were fully aware of operating in an environment marked by high linguistic fluidity and complexity for themselves and their students. This taxation on their limited target language resources added a considerable cognitive and affective burden to their already hard stretched teaching reality. They, therefore, embraced codeswitching as a scaffolding advice for the learning of new subject knowledge. This attitude I would like to call an enrichment position. It acknowledges the use of the L1 as an affective and cognitive benefit for the communication and learning process in CLIL. Similar to a translanguaging position (Garcia & Wei, 2014) in foreign language learning classrooms, teachers did not necessarily see themselves as the ever-dominant linguistic authorities but instead to a certain extent as other language learners. Having to codeswitch for lack of lexical resources was not automatically judged to be a negative and avoidable teaching technique. On the contrary, the non-language specialists even reported on using their vocabulary deficits as an incentive to involve their students into a joint and more democratic learning process7. Furthermore, codeswitching by CLIL teachers constituted a complex and intricate interplay of various principles that were clearly recognisable in their stories and actions (Golombek, 2009). It can therefore be maintained with some confidence that three of the initial guiding questions have been disproved and need to be rephrased as codeswitching by teachers has a clear pedagogical orientation, is not carried out haphazardly nor unprincipled and neither does it primarily operate as an emergency tool. Based on the findings of this study I will propose the following theses: Teachers' codeswitching in CLIL is motivated by explicit guiding principles. Contrary to the sparse research on CLIL teachers’ codeswitching (Lasagabaster, 2013; Mendez Garcia & Pavon Vazquez, 2012), it appears that teachers follow in their classroom behaviour (and explain in their reflective comments) explicit teaching principles for codeswitching in well-defined educational contexts, such as behaviour management, giving instructions, clarification sequences, furthering conceptual development, etc. However, these principles can also be in conflict with each other. For example, one of the most powerful sites of struggle appeared to be the conflict between the supremacy of content understanding (knowledge development) on the one hand and the desire to provide input for target language learning (target language development) on the other. Recent attempts at didactisising the concept of “every teacher is also a language teacher” and implementing this as a school policy (Gottlieb & Ernst-Slavit, 2014; Mehisto, 2012; Scarcella, 2003), may harmonise this conflictual attitude for the CLIL teacher and possibly advance the quality of CLIL teaching. Teachers' codeswitching in CLIL is contextually constrained. Teachers' nevertheless clearly outlined why and how they adapted their principles to macro-curricula (institutional, curricula, governmental, et cetera) and micro-curricula (classroom incidents, private personal curricula, their classroom identity, et cetera) constraints. The complex interplay guided by a process of joint negotiation affected teachers’ codeswitching decisions profoundly. Teachers' codeswitching in CLIL is domain sensitive. 7 This was also observed by (Hüttner & Dalton-Puffer, 2013; Nikula, 2010) 17 Codeswitching behaviour appears to be more frequent within certain domains and less in others. Note the relative unanimity in teachers' codeswitching for "serious" behavioural incidents on the one hand, and a wide variety of linguistic actions taken in the explanation of technical terminology on the other. Teachers' codeswitching is guided by an affective dimension. Teachers reported consistently on choosing the L1 for reasons of authenticity and forcefulness. The social management of the classroom was identified as a major playing field for emotionally motivated code switching. Given the pervasive influence and potential of codeswitching for CLIL, a final comment seems to be in place. Codeswitching must not be treated as an irritating side show in CLIL, neither from a theoretical nor a methodological perspective. Macaro’s (2014) urgent plea for more theorising of codeswitching in foreign language classrooms must be taken on board for CLIL and adapted into "how and when does codeswitching in CLIL best lead to subject learning?” 8. Therefore, critically expounding and exploiting the potential benefits of codeswitching must also become an essential component of any CLIL teacher training, whether inservice or preservice. References Atkinson, D. (2011). Alternative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition. Abingdon: Routledge. Becker-Mrotzek , M., Schramm, K., Thürmann, E., & Vollmer, H. (Eds.). (2013). Sprache im Fach: Sprachlichkeit und fachliches Lernen (Vol. Fachdidaktische Forschungen). Münster: Waxmann. Bosch, M., & Gascon, J. (2006). Twenty-Five Years of the Didactic Transposition. ICMI Bulletin, pp. 5165. Breidbach, S., & Viebrock, B. (Eds.). (2013). Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in Europe: Research Perspectives on Policy and Practice. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. Burns, A., & Barnard, R. (2012). Researching Language Teacher Cognition And Practice: International Case Studies. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. Butzkamm, W., & Caldwell, J. A. (2009). The Bilingual Reform: A Paradigm Shift in Foreign Language Teaching. Tübingen: Peter Narr. Canagarajah, S. (2013). Translingual Practice: Global Englishes and Cosmopolitan Relations. London: Routledge. Christie, F. (2002). Classroom Discourse Analysis. A functional perspective. London: Continuum. Christie, F., & Martin, J. R. (2007). Language, Knowledge and Pedagogy: Functional Linguistic and Social Perspectives. London: Continuum. Cook, G. (2010). Translation in Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University press. Coonan, C. (2007). Insider Views of the CLIL Class Through Teacher Self-observation–Introspection. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), pp. 625-646. 8 The original quote is, “how and when does codeswitching best lead to language learning” (Macaro, 2005, p. 81) 18 Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. C. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (3rd ed.). London: Sage. Costa, F. (2011). Code-switching in CLIL contexts. In C. E. Urmeneta, N. Evnitskaya, E. Moore , & A. Patino (Eds.), AICLE – CLIL – EMILE: Educació plurilingüe: Experiencias, research & polítiques (pp. 15-27). Barcelona: Servei de Publicacions de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Costa, F., & D'Angelo, L. (2011). CLIL: A Suit for All Seasons. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 4(1), pp. 1-13. Coyle, D. (2007). Content and language integrated learning: towards a connected research agenda for CLIL pedagogies. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), 543562. Coyle, D., Hood , P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content an d language integrated learning. Cambridge: CUP. Dalton-Puffer, C. (2011). Content-and-Language Integrated Learning: From Practice to Principles. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 31, pp. 182-204. Dalton-Puffer, C., & Smit, U. (2007). Empirical Perspectives on CLIL Classroom Discourse. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. D'Angelo, L. (2013). The Construction of the CLIL Subject Teacher Identity. In S. Breidbach, & B. Viebrock (Eds.), Content and Language Integrated Learning (Clil) in Europe: Research Perspectives on Policy and Practice (pp. 105-116). Frankfurt: Peter Lang. De Graaf, R., Koopman, G. J., Anikina, Y., & Westhof, G. (2007). An Observation Tool for Effective L2 Pedagogy inContent and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). The International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), pp. 603-624. Dewaele, J.-M. (2006). Expressing Anger in Multiple Languages. In A. Pavlenko, Bilingual Minds: Emotional Experience, Expression and Representation (pp. 118 - 151). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Ellis, N. C. (2013). Frequency Effects. In P. Robinson (Ed.), The Routledge Encyclopaedia of Second Language Acquisition (pp. 260-264). New York: Routledge. Ellis, R., & Shintani, N. (2014). Exploring Language Pedagogy through Second Language Acquisition Research. London: Routledge. Garcia, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Gass, S. M., Schachter, J., & Mackey, A. (Eds.). (2011). Data Elicitation for Second and Foreign Language Research. New York: Routledge. Georgiou, S. I. (2012). Reviewing the puzzle of CLIL. ELT Journal, 66(4), pp. 495-504. Gierlinger, E. (2002). Englisch als Arbeitssprache, EAC, EMI, CLIL – Österreich auf dem Weg von Insellösungen zu Strukturen. Comenius 2.1 Projekt MEMO, Pädagogisches Zentrums der Diözese Graz, Graz. Retrieved from http://www.pze.at/memo/download/05bestat.pdf Gogolin, I., Lange, I., Michel, U., & Reich, H. H. (Eds.). (2013). Herausforderung Bildungssprache - und wie man sie meistert (Vol. FörMig Edition). Münster: Waxmann. 19 Golombek, P. (2009). Personal Practical Knowledge in the L2 Teacher Education. In A. Burns, & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge Guide to Second Language Teacher Education (pp. 155-162). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gottlieb, M., & Ernst-Slavit, G. (2014). Academic Language in Diverse Classrooms. Thousand Oaks: Corwin. Grandinetti, M., Langellotti, M., & Ting, T. Y. (2013). How CLIL can provide a pragmatic means to renovate science education – even in a sub-optimally bilingual. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, pp. 354-374. Grenfell, M. (2011). Bourdieu, Language and Linguistics. London: Continuum. Hallet, W. (2013). Generisches Lernen im Fachunterricht. In M. Becker-Mrotzek, K. Schramm, E. Thürmann, & H. J. Vollmer (Eds.), Sprache im Fach: Sprachlichkeit und fachliches Lernen (Vol. Fachdidaktische Forschungen, pp. 58-75). Münster: Waxmann. Halliday, M., & Matthiessen, C. M. (2013). Halliday's Introduction to Functional Grammar (4th ed.). London: Routledge. Hüttner, J., & Dalton-Puffer, C. (2013). Der Einfluss sujektiver Sprachlerntheorien auf den Erfolg der Implementierung von CLIL-Programmen. In S. Breidbach, & B. Viebrock, Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL )in Europe (pp. 129-144). Frankfurt: Peter Lang. Hüttner, J., Dalton-Puffer, C., & Smit, U. (2013). The Power of Beliefs: Lay theories and their influence on the implementation of CLIL programmes. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 16(3), pp. 267-284. Kramsch, C. (2009). The Multilingual Subject. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Krashen, S. D., & Terell, T. D. (1992). The Natural Approach: Language Acquisition in the Classroom. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Larsen-Freeman, D., & Cameron, L. (2008). Complex Systems and Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lasagabaster, D. (2013). The use of the L1 in CLIL classes: The teachers’ perspective. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, pp. 1-21. Laufer, B. (2013). Involvement Load Hypothesis (ILH). In P. Robinson (Ed.), Routledge Encyclopaedia of Second Language Acquisition (pp. 344- 346). New York: Routledge. Laufer, B., & Nation, I. (2012). Vocabulary. In S. M. Gass, & A. Mackey, The Routlegde Handbook of Second Language Acquisition (pp. 163-176). Oxon: Routledge. Levine, G. S. (2011). Code choice in the language classroom. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. (2006). How languages are learned. Oxford: OUP. Lin, A. M. (2013). Classroom code-switching: Three decades of research. Applied Linguistics Review, 4(1), pp. 195-218. Llinares, A., & Whittaker, R. (2009). Teaching and learning history in secondary CLIL classrooms: from speaking to writing. In E. Dafouz, & M. C. Guerrini, CLIL across educational levels (pp. 73 - 88). Richmond Publishing. Llinares, A., Morton, T., & Whittaker, R. (2012). The Roles of Language in CLIL. Cambridge: CUP. 20 Loewen, S. (2011). Focus on Form. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of Research In Second Language Teaching and Learning (Vol. 2, pp. 576-592). New York: Routledge. Loewen, S. (2014). Introduction to Instructed Second Language Acquisition. New York: Routledge. Long, M. H., & Doughty, C. J. (2011). The Handbook of Language Teaching. Chichester: WileyBlackwell. Lyster, R. (2008). Learning and Teaching Languages Through Content: A Counterbalanced Approach. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Macaro, E. (2005). Codeswitching in the L2 Classroom: A Communication and Learning Strategy. In E. Llurda, Non-Native Language Teachers: Perceptions, Challenges and Contributions to the Profession (pp. 63-84). New York: Springer. Macaro, E. (2014). Overview: Where Should We Be Going with Classroom Codeswitching Research? In R. Barnard, & J. McLellan (Eds.), Codeswitching in University English-Medium Classes: Asian Perspectives (pp. 10-23). Bristol: Multilingual Matters. MacIntyre, P., & Gregersen, T. (2012). Affect: the role of language and society And Other Emotions in Language Learning. In S. Mercer, S. Ryan, & M. Williams, Psychology for Language Learning: Insights from Research, Theory and Practice (pp. 103-118). Bristol: Palgrave, MacMillan. Marsh, D. (2009). Foreword. In Y. Ruiz de Zarobe, & R. Jimenez Catalan, Content and Language Integrated Learning: Evidence from Research in Europe (pp. vii-viii). Bristol: Multilingual Matters. Martin, J. R. (2007). Construing knowledge: a functional linguistics perspective. In F. Christie, & J. R. Martin (Eds.), Language, Knowledge and Pedagogy (pp. 34-64). London: Continuum. Mehisto, P. (2012). Excellence in Bilingual Education-A Guide for School Principals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Mehisto, P., Frigols , M.-J., & Marsh, D. (2008). Uncovering CLIL. MacMillan. Mendez Garcia, M., & Pavon Vazquez, V. (2012). Investigating the coexistence of the mother tongue and the foreign language through teacher collaboration in CLIL contexts: perceptions and practice of the teachers involved in the plurilingual programme in Andalusia. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, pp. 1-20. Mitchell, R. F. (2011). Current Trends in Classroom Research. In M. H. Long, & C. J. Doughty (Eds.), The Handbook of Languaage Teaching (pp. e-book, 19422-20319). Chichester: WileyBlackwell. Morton, T. (2011). Classroom talk, conceptual change and teacher reflection in bilingual science teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, pp. 101-110. Nation, I. (2008). Teaching Vocabulary: Strategies and techniques. Boston: Cengage Learning. Nikula, T. (2007). The IRF pattern and space for interaction: Observations on EFL and CLIL classrooms. In C. Dalton-Puffer, & U. Smit (Eds.), Empirical perspectives on CLIL Classroom Discourse (pp. 179-204). Frankfurt: Peter Lang. Nikula, T. (2010). Effects of CLIL on a Teacher's Classroom Language Use. In C. Dalton-Puffer, T. Nikula, & U. Smit (Eds.), Language Use and Language Learning Include Classrooms (pp. 105123). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 21 Nikula, T., Dalton-Puffer, C., & Llinares, A. (2013). CLIL classroom discourse: Research from Europe. Journal of Immersion and Content-based Language Education, 1, pp. 70-100. Perez-Canado, M. (2011). CLIL research in Europe:past, present, and future. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, pp. 1-27. Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2002). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: CUP. Saville-Troike, M. (2006). Introducing Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cmabridge University Press. Scarcella, R. (2003). Academic English: A Conceptual Framework. Retrieved January 12, 2015, from University of California linguistic minority research Institute: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6pd082d4 Schleppegrell, M. J. (2004). The Language of Schooling: A Functional Linguistics Perspective. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (2013). A Vygotskyan sociocultural perspective on immersion education: The L1/L2 debate. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, pp. 101-129. Tokowicz, N. (2013). Revised Hierarchical Model. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Routledge Encyclopaedia of Second Language Acquisition (pp. 559-562). London. Turnbull, M., & Dailey-O'Cain, J. (2009). First Language Use in Second and Foreign Language Learning. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. Van Lier, L. (2004). The Ecology and Semiotics of Language Learning. Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Viebrock, B. (2012). "The Situation in the CLIL Classroom Is Quite Different"-or is it? Teachers' mindsets, Methodological Competences and Teaching Habits. In D. Marsh, & O. Meyer (Eds.), Quality Interfaces: Examining Evidence and Exploring Solutions in CLIL (pp. 79-90). Eichstaett: Eichstaett Academicemic Press. Vollmer, H. J., & Thürmann, E. (2013). Sprachbildung und Bildungssprache als Aufgabe aller Fächer der Regelschule. In M. Becker-Mrotzek, K. Schramm, E. Thürmann, & H. J. Vollmer (Eds.), Sprache im Fach: Sprachlichkeit und fachliches Lernen (Vol. Fachdidaktische Forschungen, pp. 41-57). Münster: Waxmann. Wannagat, U. (2007). Learning through L2 – Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) and English as Medium of Instruction (EMI). International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), pp. 663-682. Yerrick, R., & Roth, W.-M. (2005). Establishing Scientific Classroom Discourse Communities. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 22