Group Dynamics I. The Nature of Groups

advertisement

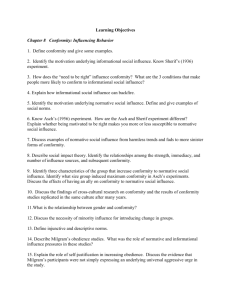

Groups & Group Dynamics Satisfy survival, psychological, informational, & identity needs Structure of small groups – norms; roles, status systems How individual’s thoughts, feelings & actions are influenced by being part of a group; how individuals can affect groups What are groups? Groups differ in their degree of commitment & social cohesiveness. Incidental groups - minimal group paradigm (workshop at a conference) Membership groups - defined by being a member (committee, club) Identity-reference groups – affiliation acts as a reference frame for social identity (religious community, political affiliation) People in individual interaction with each other - - - People acting as a group Social Influence in groups Social loafing (idling) - where people have little or no involvement or commitment to group, individualistic norms, no investment in what happens – impact of group on individual behaviour is negative/minimal Social facilitation (energizing) - working harder as a member of group than alone, task important/interesting, strong commitment to goal (Collectivist cultures) Social loafing = experimental artefact of creating incidental groups (low commitment, meaningless tasks), not a universal quality of task performance in a group Groups that have (collectivist), or are motivated to develop, cohesiveness, commitment, & work on worthwhile task, social energising more likely Identity-reference groups Shift from personal to social identity Becomes in-group, encourages cooperation & conflict with outgroups Summer Camp experiments (Sherif et al. 1961). White middle class 11-12 year old boys at summer camp 4 phases: Spontaneous friendship formation Ingroup formation (2 groups formed, kept separate) Intergroup competition (placed in competitive situations) Intergroup cooperation (create superordinate goals achieved only through intergroup cooperation) Conformity Allport 1924 groups tend to give more conservative judgments than individuals Sherif 1936 autokinetic effect Asch’s studies (1951) Group norms – shared standard of conduct expected of group members Garfinkel 1967 students behave as lodgers Festinger 1954 Social Comparison theory Minority Influence Asch: majority influence – many factors but most important = being only dissenter in group. Effect extinguished where subject has even one supporter. So easier to resist if not ‘odd one out’; But can you persuade others to move to your position? Moscovici et al. 1969 study of colour perception (groups of 6, incl. 2 stooges, blue/green slides) Some members of majority can be persuaded by small minority IF their judgments are consistent Also important how behaviour of minority is interpreted. Two main processes What kind of decision is it? (e.g., intellectual vs. judgmental) How will the decision be made? Normative vs. informational social influence Heuristic vs. systematic processing Majority influence on group decisions. majorities can exert greater normative and informational social influence than minorities. majority influence (Asch’s 1950's classic studies) compliance minority influence (Moscovici 60's/70's) – conversion Explanations for Social Influence Processes in groups Same Process Models Dual Process dependency model (Turner 1987) : Normative & Informational influence contribute differentially in different situations Where confident of own judgment, + majority perceived as powerful, then Normative influence predominates Where lack confidence, so conflicting info from minority can have greater impact, majority less powerful, then normative influence reduced Different Process Models Moscovici’s Innovation Model – based on social representations (how new ideas of original thinkers come to influence the images, thinking, vocabulary & beliefs of ordinary people) Majority influence operates through conformity & normalization, passive heuristic processing Minority, through a discrete process of innovation, direct processing effort – consistency is key – sustained attempt to exert information influence (real-life pressure groups - Amnesty Int, Greenpeace) Turner's Referent Information Influence model 1991 (based on social identity theory) 3rd form: referent information influence operates through people’s self-categorization Identify oneself with a group, then use that group’s norms as standards for own decision making Group discussion enhances the initial attitudes of people who already agree. Are group decisions more cautious? Research has shown shifts both toward caution and toward risk. Group enhancement of initial tendencies: groupproduced enhancement or exaggeration of members' initial attitudes through discussion = group polarization. ‘Brainstorming’ • What produces group polarization? A special case of the ‘risky shift’ (Stoner 1961) Social comparison explanation: individual members discover that they are not nearly as extreme in the socially valued direction as they initially thought. Because they want others to evaluate them positively (normative influence), begin to shift toward even more extreme positions. Persuasive arguments explanation: hearing more arguments in favour of their own position rather than against it, and hearing new supportive arguments that they had not initially considered, members gradually come to adopt even more extreme positions. Both explanations play a role. C. Groupthink (Janis 1971, 1982) when consensus-seeking overrides critical analysis. Symptoms of groupthink overestimation of in-group close-mindedness increased conformity pressures Research on groupthink - does not always occur in the way Janis proposed. NOT found in groups outside lab – why? Key = different norms. IV. Leadership • • • • • A leader is an influence agent. Transformational leaders take heroic and unconventional actions. The contingency model Fiedler (1967, 1978) highlights personal and situational factors in leader effectiveness. Gender and culture can influence leadership style. Importance of task (group effectiveness combination of leadership style & group task) E.g., jury foreperson–perceived as leader, it is usually men of higher SES (socio-economic status), might influence the verdict, although evidence is mixed here. VI. Applications: How Do Juries Make Decisions? Minority influence upon others’ verdicts – a small minority may influence the majority vote by conversion, if they are consistent, committed in their opinions and arguments, seem to be acting on principle rather than out of self-gain and incur some cost, as well as are not overly rigid and unreasonable in their opinions and arguments. Social / majority influences on jury decision-making – jurors have usually decided on a verdict before they retire to deliberate and jury deliberation consists merely of trying to persuade others to the same opinion. Social group pressure may thus lead to illogical decisions for a number of reasons: group polarisation – a group tends to make more extreme decisions (either riskier or more cautious) through a process of social comparison and increasing conformity to the group’s initial majority decision; conformity – group pressure to agree with majority verdicts may result in a lack of consideration for alternative, minority opinions. This can be both informational (uncertainty over the verdict) and normative (need to be socially approved). The pressure may increase with the severity of the crime, the need for a majority rather than unanimous verdict (whoever cares about one or two dissidents then...), and the size of the jury (1 against 5 people resists less than 2 against 10 people – see Asch); Groupthink – esp. in a cohesive and isolated group, dominated by a directive leader – e.g. confirmatory bias – not equally considering evidence against their joint beliefs; Social loafing – individuals in the jury may be inclined to deliberate less that they would alone and let others think for them. Reading General: Ch. 8 & 9 Hogg & Vaughan Critical evaluation: Pheonix, A. (2007) Chapter 5 Intragroup processes: Entitativity. In D. Langdridge & S. Taylor (Eds.). Critical Readings in Social Psychology. OUP. Wekselberg, V. 1996 Groupthink: A triple fiasco in social psychology. In C.W. Tolman, F. Cherry, R. van Hezewijk & I. Lubek. (Eds.). Problems of Theoretical Psychology. Ontario: Captus Press. Fraser & Burchell Ch. 8 (esp. discussion of normative vs. informational influence)