Stella Stella Ola - The University of Texas of the Permian Basin

Childhood Games

Childhood Games

By Kathryn J. Siepak, PhD

The University of Texas

of the Permian Basin

1

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 2

Childhood Games

Children of all ages, abilities and cultures need to play. Yet, there is currently strong pressure on schools and early childhood programs to prove that teachers are teaching and children are learning, so that taxpayers can be reassured that they are getting their money’s worth. The general public does not consider play a productive use of classroom time. And sometimes, it isn’t.

Aimless, undirected play with no guidance from teachers is not necessarily a valid academic activity. But when children’s play is purposeful, challenging, and facilitated by teachers, play can provide valuable opportunities for cognitive, physical, social, language and emotional development.

Teachers should be able to define, understand, explain the importance of play and recognize the opportunities for children to learn from play so teachers can facilitate children’s play and help them learn. Teachers might need to justify to their director or principal the time they spend letting children play, so should be able to describe children’s play in academic terms and to articulate what children are learning through play. Also, teachers will sometimes need to explain to parents what children gain from engaging in quality play.

Understanding Play

What is play? It is an activity that a person chooses to do, enjoys doing and can shape or control to a desired outcome. It is not something we are told to do, must do in order to fulfill an obligation, or have to perform in a certain manner.

An activity can be playful in some circumstances, but work in others. For example, having to draw the life cycle of a frog for an assignment is not play; drawing a frog might be play, if the child chooses to draw it. Playing Lotto in the classroom to learn letters or multiplication tables may be a fun learning activity, but it is not play if the teacher decides when the children can do it and makes all children participate.

Because play is so individual and can include so many different kinds of activities, you might think that there is no way to understand play in general terms. But people who observe children have found two ways to talk about play.

There are different types of play and different social structures in play. These types and social structures can be combined in many different ways, but knowing the five types and four social structures, teachers can understand the nature of children’s play. When the director, principal or other observers visit the classroom, teachers can describe the types and complexity of children’s play.

Types of Play:

1.

physical—movement that is fun, pleasant or challenging. Examples: swinging, riding tricycles, running, climbing trees

2.

exploratory—play that is directed toward discovering properties of a material or object. Examples: sand and water play, playdoh (not making a product)

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 3

3.

creative/constructive—building, artistic or putting materials together in some way. Examples: drawing, blocks, playdoh (product in mind)

4.

dramatic (also called pretend)—imagining a realistic or fantastic situation in which children act out different roles. Examples: being firemen or puppies, playing with dolls or action figures.

5.

games with rules—activities with agreed-upon rules; can be competitive (one winner) or cooperative (everyone wins). Examples: tag, hide and go seek, sports, Candyland.

I’ve made up a rhyme to remember these five types of play. You can do it as a hand-clapping game:

Swing, swing, bird on the wing!

Explore, explore: what’s it for?

Build, build, build a house!

Be, be, be a mouse!

Hide and Seek, don’t you peek!

Swing stands for physical play, like swinging high.

Explore: what’s it for? stands for exploratory play, like wondering what a funnel is for.

Build a house stands for creative or constructive play, building or making something you’re proud of.

Be a mouse Is a child pretending.

Hide and Seek is a common game with rules.

Why is it important to know the five types of play? One kind of play is not better than another, but it is important to encourage children to try different types of play. Creative/constructive play is more complex than exploratory because there is an end product in mind and children have to figure out how to get to their goal. Dramatic play and games with rules are more complex types of play when they include interaction with other children than when children are playing alone. Teachers should encourage children to engage in more complex types of play if they notice a child seems “stuck” in a particular type of play day after day and week after week.

Other warning signs that a child may need help learning how to play are aimless wandering or always just watching others play and not knowing how to join in (Berk, 2010). Children who cannot seem to stay with one activity long enough to become absorbed mentally can be encouraged when teachers ask challenging or engaging questions such as, “How many scoops will it take to fill that bucket?” Children who seem to be engaging in exploratory or constructive play, but who are actually doing repetitive or compulsive activities (e.g., lining cars up around the room in a specific pattern) may need screening for developmental disabilities if this type of play occurs frequently and children

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 4 cannot be persuaded to try other kinds of play (e.g., pretending to have a car race).

Social Structures of Play:

1.

solitary—a child plays alone, absorbed in his activity and unaware of other children. A child might be busy digging a hole in the sandbox with a bulldozer.

2.

parallel—two (or more) children do the same activity near each other, but do not talk or interact with each other. Example: two children digging their own holes in the sandbox.

3.

associative—children are doing their own activities, but interact or share materials. For example, two children digging their own holes, but sharing a shovel and a bucket.

4.

cooperative—children play together with a common goal. Example: the whole group is working together to dig a hole to China.

I made up a way to remember these four types of play:

Alone, a track, we share, let’s go there.

Alone stands for solitary play.

A track stands for parallel play, like the two railings of a railroad track that never cross each other.

We share stands for handing toys back and forth, like in associative play.

Let’s go there stands for the way children in cooperative play have a common goal.

Why is it important to know the four social structures of play? This list, from solitary to cooperative, goes from the simplest to the most complex social structure. There are two reasons this is important. First, teachers need to understand the social play that children of different ages are capable of. Very young infants will engage in solitary play, then parallel play as they get older.

Three year olds are just beginning to learn associative and cooperative play, but games with rules might require a high level of cooperation that they are not quite ready for. Preschoolers and kindergartners can begin to learn games with simple rules and enjoy developing elaborate dramatic play scenes together. But keep in mind that older children and even adults will engage in solitary or parallel play, although they are capable of complex cooperative play. This is not cause for alarm.

It is also important for teachers to know the progression from simple to complex so that they can help children move to more challenging forms of social play as they become ready for it. Depending on their age, children who don’t speak the same language as other children may be encouraged to engage in parallel play, then associative play until they finally gain the confidence to join in

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 5 cooperative play. As another example, it would be difficult to force a child with autism from solitary play into cooperative play, not matter how old he was.

Children with autism may not engage in cooperative play at all. But being close and engaging in parallel play may be an effective way to be social with an autistic child.

Importance of Play

The phrase, “learning through play” often brings to mind children counting dolls at the table and then counting enough plates to serve them all. Or teachers might get children to practice vocabulary words while they are playing by asking,

“What color is that?” or “What shapes do you see here?” Practicing skills like counting in the context of play are certainly more enjoyable and more effective than counting birds on a worksheet or “coloring the circle red.” But play provides opportunities for so much more: problem solving, open ended questions, divergent thinking, social competence. Teachers must watch children, listen to them, ask questions, challenge them, and take every opportunity to get children to think, express their ideas, explain their plans, reflect on their activity and explore their feelings and the feelings of those around them.

Even so, there is a lot that children learn through play that is not necessarily teacher-driven and academically-based. Through play children also learn social skills and develop a sense of themselves. They learn cooperation, belonging and conflict resolution. They learn what they like, what they’re good at, and what other children like about them. Children acquire motor skills, the ability to inhibit their impulses, rhythm and creativity. Play is important for many reasons (it’s fun!), but I want to focus on one reason in particular. Play

develops children’s motivation to learn. They must be motivated to learn in order to be successful in academics and in life in general.

People who study motivation, or the desire to do something, have found that there are two approaches to learning. Some children have what’s called a

mastery orientation, or learning-goal orientation. That means that when they are learning something new, they try to master the task, to get good at it with effort and information. Their goal is to learn. Children with a mastery orientation do well in school and become competent adults. They understand that their effort makes a difference in their world.

Other children have what’s called a performance orientation, or learned

helplessness. Their goal in learning something new is to fulfill a requirement, show everyone that they can do it, to earn a grade, or to be better at it than everyone else. They are trying to win approval instead of trying to learn whatever it is they are learning. If it turns out that they can’t do it, they blame it on everything but themselves. They may develop an attitude called “learned helplessness” that means they don’t even try to learn because they believe they are helpless and have no control over their world.

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 6

What does this has to do with play? Through play, children develop a

mastery orientation. They have repeated opportunities to control or shape their activities. Remember the third part of the definition of play: the person has the ability to shape the outcome of the activity. They see the direct and immediate results of their actions. They learn that they are powerful and can make interesting things happen. Experiences that allow children to master their environment help develop a mastery orientation. Children learn that their efforts and their learning make a difference. Through play, children develop an attitude of “I can do this.” If something they try to do is difficult, like stacking a tall tower of blocks--or learning the multiplication tables--they stick to the task, because they know that their effort and persistence will make them successful. Play is important because it provides real-life practice of academic skills, creates opportunities for teachers to challenge children to use critical thinking skills, gives children the physical movement they need to be healthy and fit, and gives them the control over their environment that they need in order to develop a mastery orientation towards the world of learning.

Guidelines for Modifying Games

According to Block (2000), there are four guidelines for modifying games to accommodate children with special needs (as cited in Ohtake, 2004):

1.

Safety: The games should be safe for everyone, even in their modified form. For example, a wheelchair in the middle of a heated game of tag might be a tripping hazard. Instead of allowing children to run, challenge them to play tag on all fours.

2.

Challenge: Encourage children to use all of their abilities

(physical, cognitive, language, social) in order to participate.

3.

Integrity: Make sure that the modified rules are not unfair to children without disabilities. A focus on cooperative games rather than competitive games will help avoid this problem.

4.

Practicality: The modifications should take into account existing resources and adult help. If it is not practical to give every child on the team a wheelchair to play basketball, then find an alternative modification.

Ohtake (2004) adds a fifth guideline:

5.

Meaningful Participation: When children with special needs are on a team, their participation should contribute to the score in creative ways. See the handout, Meaningful Inclusion of ALL

Children in Team Sports.

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 7

The above guidelines could also apply when children from other cultures participate in play. But here are some additional guidelines for facilitating the participation of children with limited English:

1.

Demonstration: SHOW children how to play and what the rules are while explaining them verbally.

2.

Observation: Let children with limited English observe one round of the game first

3.

Monitoring: Watch closely as they join in.

4.

Correction: Give feedback if there are misunderstandings.

5.

Compassion: Help other children understand that their playmate might not be clear about the rules at first.

Sportsmanship

Deciding on a Game

This age-old problem is usually solved by the teacher. But children learn negotiation skills when they are the ones to decide what game to play. Teachers should monitor the power dynamics of the group, to be sure that one child does not get to decide the game every time. A talk about leadership skills may help nurture budding leaders to step forward to develop their ability to lead the group.

Because children often have not had many opportunities to practice group negotiation, I invented what I call the “Game Can.” It is a large container that holds a laminated card with pictures and directions of each game I have taught the children. After the group decides which child will be the Chooser, he/she closes his/her eyes and selects a card from the container. That’s the game the group will play.

Also, teachers can use the Game Can to remind children of games they have not played in a while.

Choosing Teams

Counting Off

Children decide on how many teams are necessary, for example, three. Starting with “one” and counting up to however many teams are needed, each child says a number. Then all the “ones” are on a team, all the “twos” form the next team, and so on.

Pairing off

Sometimes strength and size matter in a game. So children pair up with someone the same size as themselves (size, not age!). Then each pair splits, one on one team and the other on the other team.

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games

Alphabetical Order

Older children can get in line by the first letter of their first name. Then divide the line in half to form the teams.

8

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 9

Ways to Decide Who Is “IT”

Many games have one person who begins the game. Sometimes being It is a desirable position (for example, the person who walks around the circle, tapping players on the head and saying, “Duck, Duck, Goose”). Sometimes being

It is not a desirable position (being “It” in a game of tag). Often adults choose this person for the children, but it’s better to teach them several ways to decide on who’s “It” so they learn how to make group decisions. Still, adults should listen in and make sure children are being fair and that different children start the game every time.

Children with cognitive impairments such as Down’s Syndrome will need lots of practice understanding these “pre-game” rituals. Children learning English may have a hard time understanding the words to the counting-out rhymes, because the words are sometimes separated into syllables in a sing-song voice.

Be sure to explain the words to the rhymes, including the fact that some of the words are nonsense (for example, Eenie Meenie Miney Mo).

Not IT!

As soon as children agree on a game to play, the LAST person to shout out,

“NOT IT” has to be “It.”

Eenie-meenie-miney Mo

A classic with many rhyme variations, children put their fists* (either one or two) in a circle and the Caller (make sure it’s a different person each time) taps out the words of the rhyme on the fists provided, going around as many times as necessary until the final word. The fist that gets the final syllable is taken out of the circle. The rhyme is completed as many times as necessary until there is only one fist remaining. Children MUST decide in advance if the FIRST child out becomes It or if the LAST child remaining is It. Usually if there is a large group of children who are eager to start the game, they decide that the first person out is

It. Sometimes the Eenie meenie miney mo is half the fun! (WARNING: In the distant past, children sometimes used derogatory words or curse words in some of the rhymes. Demand respect toward all people at all times.)

Here is one variation:

Eenie meenie miney mo

Catch a monkey by the toe.

If it hollers, let it go.

Eenie meenie miney mo.

Sometimes children add on:

My mother told me to pick the very best one

And it is Y-O-U.

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 10

Another similar fist-tapping rhyme is:

One potato, two potato, three potato, four

Five potato, six potato, seven potato, ore!

*Sometimes children put their feet in instead of their fists, just to change things up a bit!

Wild-card Rhymes

Because older children can often figure out who will be counted out before they begin tapping out the rhyme (and sometimes use this knowledge to their own advantage!), children have devised a questioning strategy. The setup is the same as for Eenie meenie miney mo (circle of fists), but a question is asked in the middle which changes the ending syllable so no one can figure out where the rhyme will end.

An example:

Bubble gum, bubble gum

In a dish.

How many pieces do you wish?

[Child whose fist is tapped on “wish” names a number]

“Three”

[The tapping continues, either counting out the number or spelling out the number word.]

1-2-3 or “T-H-R-E-E”

Another example:

Engine, engine Number 9

Going down Chicago line

If the train should jump the track,

Do you want your money back?

[Child whose fist is tapped on “back” says yes or no.]

Y-E-S spells yes (Or N-O spells no).

Drawing Straws

Another classic that really works! Children decide in advance if the shortest straw will be It or the longest straw will be It. Then everyone picks a stem of grass or small twig and gives it to the Holder. The Holder makes sure all the tops of the stems are even while hiding the other ends so no one can see the different lengths. Then the person who drew the shortest/longest straw will be It.

Simple Cooperative Games

On the following pages you will find descriptions of many types of games, the ages that are suited to them, how you might modify them for children with special needs or children who do not speak English, and what children may be able to learn from the games. Teach children how to choose what game they will play, how to decide who goes first or who’s It, and how to play with a minimum

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 11 of adult direction. But always watch children’s social interactions, sportsmanship, safety and inclusiveness. It’s never fun to be left out or blamed for mistakes.

Sneaky 3 years and up

One child is the Looker and the others are the Sneakers. The Looker stands in the middle of the room. All Sneakers start out lying down scattered around the room. As the Looker moves SLOWLY around the room, the Sneakers get up and move behind the Looker’s back. If the Looker turns around, the Sneakers freeze.

But as soon as the Looker turns away again, the Sneakers try to move around without being seen. If the Looker sees someone moving, s/he calls the Sneaker’s name and the Sneaker has to sit out. For young children, as soon as the next person is caught sneaking, the first child out can re-join the game. Older children may enjoy the challenge of the Looker trying to catch all of the Sneakers, so

Sneakers who were caught sit out until there is only one Sneaker left.

Modifications:

For English language learners, no modification is necessary after the game has been demonstrated.

Children with visual impairments: The Sneakers could wear ankle bands with a bell attached, balls of paper taped to the soles of their shoes, or some other noisemaker. The challenge is to stop making noise when the Looker is nearby.

What children learn:

Young children need practice inhibiting their impulses. All children learn to watch the Looker carefully, which builds attention span. Sneakers learn strategy as they plan their moves and stops. Lookers use observation skills and strategy to catch the Sneakers.

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 12

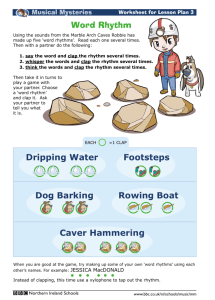

Hand Clapping Games 5 yrs. and up

Children worldwide engage in clapping games in which two or more children sing songs or chant rhymes to the rhythm of elaborate clapping sequences.

Remembering the words and performing the clapping sequences at the same time is a cognitive and physical challenge. Young children need to start with simple clapping and short, repetitive songs. Older children can make up their own rhymes and invent new clapping sequences.

Here are just a few:

Say say oh, playmate,

Come out and play with me

And bring your dollies three,

Climb up my apple tree

Slide down my rainbow

Into my clubhouse door

And we’ll be jolly friends

Forevermore more more more more.

Say say oh, monster,

Come out and fight with me

And bring your lizards three,

Climb up my old dead tree

Slide down my lightning

Into my cellar door

And we’ll be jolly monsters

Forevermore more more more more.

This is one my daughter and I made up:

C-O-L-L-E-G-E

College is the place for me!

I will go and you will, too.

There is nothing we can’t do!

Play the march and hear them sing

Grad-u-ation is my thing.

C-O-L-L-E-G-E

College is the place for me!

Modifications:

Children may not be able to do both clapping and singing at the same time. They can do the clapping while you sing, or they can sing while you do the clapping.

Explain and illustrate the words to children who are learning English. Make sure they know that some of the words are nonsense.

What children learn:

Physical precision, creativity in making up their own rhymes. Some children have a hard time negotiating a relationship with more than one child at a time. Pairing up provides a one on one situation that eases tensions in small groups. Good for getting children to play with someone new.

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 13

Bum Bum Bum

Imaginative Group Games

Best with mixed ages, 4 – 10 years

This is an elaborate charades game, with one team acting out an occupation and the other team guessing what they’re acting out. Team 1 huddles together and decides on an occupation to act out. Children take on different roles (e.g., a hair salon with hairdressers, customers and a perhaps customers waiting, reading magazines), or they can all do the same thing (e.g., picking apples). When ready, Team 1 marches over to Team 2, chanting:

Team 1: Bum, bum, bum, here we come, all the way from Washington!

Team 2: Where y’all from?

Team 1: Pretty People Station.

Team 2: What’s your occupation?

Team 1: Any ol’ thing!

Team 2: Then get to work!

Then Team 1 pantomimes the occupation. Team 2 tries to guess the occupation.

If they get it right (Team 1 decides ahead of time what they’ll accept as “right”, for example, hair salon, hairdresser, or beauty shop, but not barber shop), then

Team 1 runs back to their home base while Team 2 tries to tag as many of Team

1 as they can. Then Team 2 decides on an occupation and the teams reverse roles.

Modifications

This game adapts easily to multiple abilities, due to its creative nature. The tag game at the end can be omitted if children with mobility difficulties are participating and safety is an issue.

Second language learners or children from very different cultures will need to be given specific tasks, as they may not be familiar with various occupations.

What children learn:

Being part of a team, children have to negotiate group decision-making. Children may learn details about jobs that they did not know. Children also become experts on jobs they do know about. Pantomime requires precise physical movements and active imaginations.

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 14

Swing the Statue ages 3 and up

This game takes close monitoring by adults at first, to make sure children are playing safely. Children decide who the “Swinger” will be, hopefully choosing one of the larger children in the group. The Swinger holds both hands with one child and GENTLY swings him/her around a couple of times, letting go suddenly.

The Statue freezes in whatever position s/he lands. The Swinger has to be careful not to swing the Statue into another Statue.

After creating a gallery of statues, the Swinger walks around to each statue and activates it by tweaking an ear, tugging a toe, pushing a nose or some other movement. The Statue can decide what movement will activate him/her, but after three tries, the Statue must begin.

The Statue moves in such a way as to give an idea as to what s/he represents.

For example, a child landing on all fours might be a horse or a dog. A child landing upright with hands at hips might be a rock guitarist. The Swinger gets to guess what the Statue is. Then that Statue gets to activate the next Statue and so on, until it’s time to choose another Swinger or go home.

Modifications:

If swinging is impossible or gets out of hand, the Swinger can hide his/her eyes while the Statues move wildly around until the Swinger shouts, “STATUES” or

“GALLERY” if you want to teach children what an art gallery is.

Children with limited English can usually join right in, due to the creative and non-verbal nature of this game.

What children learn:

They are creative problem solvers when they figure out a logical movement from the frozen position in which they land. The Swinger/Guesser has to figure out what the Statue represents. Children learn a sense of personal space. Children learn self-control both in being a gentle but effective Swinger and by freezing as a Statue. Children may learn vocabulary words, if they teach each other what they are representing.

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 15

Multicultural Games

Snail, Snail Best with mixed ages, 4 – adult

This is a very old large group game from England and the British Isles. Everyone gets in a large circle, holding hands. Older children and adults should be next to younger children. Then the circle breaks into a line, with the leader pulling everyone along through various formations. Below are several common formations. You can also be creative and make up your own. Here is the song:

Snail, snail come out and be fed.

First your feelers, then your head.

Then your mama and your papa

Will feed you fried mutton.

(Mutton is the meat of sheep, a common food in Britain.)

Thread the Needle: The first two people in line form a bridge, letting go of the third person’s hands. The third person becomes the new leader, ducking under the bridge and marching on. When the last person goes under the bridge, the two bridge people grab on to the end of the line.

Spiral: The Leader marches the line into a smaller and smaller spiral, until s/he is at the center. Then the first two people form a bridge like Thread the Needle.

The new leader then spirals everyone back out of the circle in the opposite direction. The bridge people join at the end. When this is done correctly, the group ends up in a circle facing outwards instead of inwards.

Skin the Snake: This is a bit tricky, but if you instruct everyone to “do what the person in front of you does” then it will work. It is essentially a whole line of

Thread the Needles, in a formation that looks like a snake shedding its skin.

Here’s how it works: the Leader forms a bridge with the second person in line.

The third person continues leading the line under the bridge. When the third and fourth people have gone under, they also form a bridge. Then the fifth and sixth people continue under both bridges and form their own bridge after going under the others. What happens is that a long line of bridges forms, with the “snake” passing underneath it. When the end of the line comes, the first bridge breaks and grabs on to the end. They will continue to pass under all the other bridges, who also break and grab on to the end after the last person has gone through.

Eventually the last bridge breaks and grabs on, and the line is back to its original form.

Modifications

Children with mobility challenges can be permanent Bridges that the chain of people go under. They can hold up sticks to extend their arms if the group

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 16 cannot bend low enough to go under. There could be a caller who shouts out the formations for the group to perform.

English Language Learners will need an explanation of the words to the song, but no other modifications are needed. It would be best to place them in the middle of the line for the first few times of playing, so they are not suddenly the leader.

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 17

Stella Stella Ola Ages 7 - 10

This is a good game for a large group of children, like when you’re waiting for the buses to come while you’re on a field trip. Basically, you “pass” a clap around the circle in rhythm to a song. There are many different songs for this game, many from Canada. This is a version from North Carolina:

Stella Stella Ola, quack quack quack

Singing S chigga chigga chigga chigga track

Singing S chigga chigga, flo-ow, flo-ow, flow, flow, flow – GO!

One, two, three, four, FIVE!

Everyone stands in a circle, with both palms up; the right palm on TOP of your neighbor's left palm. At the beginning of the song, the leader claps his/her right hand over to the left hand, but actually claps his/her neighbor’s hand, which is on top of her left hand. This second person then repeats the action with her right-hand neighbor, etc., so the clap goes all around the circle. After the one clap, each person returns the right hand to rest on top of his/her neighbor’s left hand.

The goal is to NOT get your palm slapped at the end of the verse. When the countdown gets to "FIVE", if the last child moves his/her hand out of the way in time, the child doing the clapping is out. If, on the other hand, the child doesn't get his/her hand out of the way, s/he is out. Whoever is out moves to stand in the middle of the circle. Once several rounds have been played and there are three or four people standing in the middle of the circle, they can begin their own smaller circle and keep playing! The more players you have, the more concentric circles you can get.

Modifications:

If there is a child who uses crutches, all of the children can sit on the ground.

If this is not possible, then the child with crutches might sit in a chair. Another modification is to pair children who need postural support or help moving their arms with an adult who stands behind the child to help.

Slow down the song for children with cognitive impairments or speech difficulties. Allow children to do the hand clapping without singing or to just sing and not participate in the clapping.

Second language learners should be told that the words do not really mean anything.

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 18

Dr. Knickerbocker Ages 4 - 10

This game is similar to Stella, Stella Ola in that there is a count around the circle that ends with someone going into the center to start a new circle. However, this game is easier for younger children whose right and left hands are easily confused.

Everyone stands in a circle. The clap sequence is:

Doc- (slap thighs)

-tor (clap own hands together)

Knick (clap one hand on each side with the person next to you, both hands at the same time)

-erbocker, Knickerbocker, you’re the one! (Now alternate clapping your own hands with clapping hands with the people on each side of you in the rhythm of the song)

You sure know how to have some fun.

Now let’s get the rhythm of the hands (clap own hands twice: clap clap)

Now we’ve got the rhythm of the hands (clap clap)

Now let’s get the rhythm of the feet (stomp, stomp)

Now we’ve got the rhythm of the feet (stomp, stomp).

Now let’s get the rhythm of the hips, boom, boom!

(bump hips from side to side)

Now we’ve got the rhythm of the hips, boom, boom.

Now let’s get the rhythm of the eyes, wooo! (Look upward and throw hands up in the air)

Now we’ve got the rhythm of the eyes, wooo!

Now let’s get the rhythm of the number 9.

At this point, the chosen leader stands in the middle of the circle, spins around with eyes closed, and points at one person. This person begins the count, saying,”One”, then the count goes around the circle (two, three, etc.). The person who says,”Nine” has to go to the middle of the circle. Then the whole song is sung again. The newest person sent to the center will be the spinner who chooses the next number “One”.

You can choose any number (within reason!) to practice counting.

Modifications:

Same as for Stella, Stella, Ola

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 19

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak

Childhood Games 20

References and Resources

Block, M. E. (2000).

A teacher’s guide to including students with disabilities in general physical education. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Ohtake, Y. (2004). Meaningful inclusion of all students in team sports. Teaching

Exceptional Children, 37(2), 22 – 27.

© 2013 Kathryn J. Siepak