Active Site - Personal Webspace for QMUL

advertisement

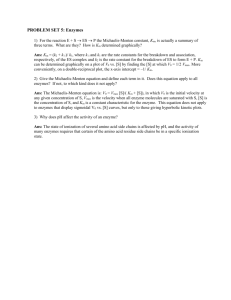

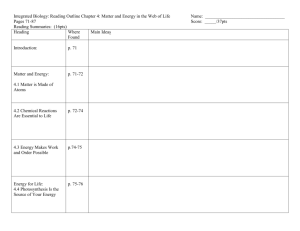

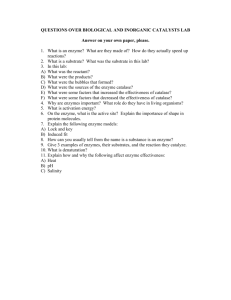

Lecture 9 Enzymes: Basic principles SBS017 Basic Biochemistry Dr. Jim Sullivan j.a.sullivan@qmul.ac.uk Learning Objectives Lecture 9 • You should be able to able to define the terms Enzyme, Specificity and Co-factor • You will understand the concept of Gibbs Free Energy and its relation to reaction equilibrium • You will be able to describe how enzymes effect the rate of biological reactions and be able to define the term Activation energy in the context of Transition state theory Enzymes • Biological catalysts • Almost all enzymes are proteins (but RNA can have enzymic activity too, “ribozymes”) • Function by stabilizing transition states in reactions • Enzymes are highly specific Enzymes accelerate biological reactions • e.g. Carbonic Anhydrase • CO2 + H2O H2CO3 • Each molecule of enzyme can hydrate 1,000,000 molecules of C02 per second, 10,000,000 times faster than uncatalysed reaction Catalase • 2H2O2 2H2O + O2 Enzymes are highly specific e.g Peptide bond hydrolysis (proteolysis) A. Trypsin cleaves only after arginine and lysine residues. B. Thrombin cleaves between arginine and glycine only in particular sequences. But Papain cleaves all peptide bonds irrespective of sequence. Specificity is important e.g. DNA polymerase I Adds nucleotides in sequence determined by template strand. Error rate of < 1 in 1,000,000 Due to precise 3D interaction of enzyme with substrate Many enzymes require cofactors Cofactors are small molecules essential for enzyme catalysis Can be: i.Coenzymes (small organic molecules) ii. Metal ions Holoenzymes Enzyme without its cofactor “apoenzyme” With its cofactor “holoenzyme” Cofactors are essential for activity e.g. many vitamins are cofactors, many diseases associated with vitamin deficiency due to lack of specific enzyme activity Energy transformation Many enzymes transform energy into different forms Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) is universal currency Light ATP Photosynthesis Food ATP Respiration ATP work ATP is an energy carrier e.g. ATP provides energy to pump Ca2+ across membranes Free energy The free energy of a reaction is the difference between its reactants and its products This called the ΔG If ΔG is negative, the reaction will occur spontaneously “exergonic” If ΔG is positive, energy input is required “endogonic”: Endogonic reactions Energy (G) Products ΔG positive Reactants Reaction coordinates Exergonic reactions Energy (G) Reactants ΔG negative Products Reaction coordinates Exergonic reactions Energy (G) H2O2 ΔG negative 2H2O + O2 Reaction coordinates ΔG is independent of reaction path Energy (G) Reactants ΔG same Products Reaction coordinates ΔG and reaction equilibria • A negative ΔG indicates that a reaction can occur spontaneously not that it will • ΔG tells us nothing about the rate of reaction only the energy of its end points • The rate of reaction is defined by the equilibrium constant The equilibrium constant Keq A+B C+D [C][D] Keq [A][B] Calculating ΔG The free energy of a reaction is given by: [C][D] G G RT ln [A][B] • Where ΔG° is the standard free energy change (i.e. change at 1M concentrations), R is the universal gas constant and T the absolute temperature Calculating ΔG at pH7 (ΔG’) At equilibrium and standard pH7: [C][D] 0 G'RT ln [A][B] Calculating ΔG at pH7 (ΔG’) Rearrange and substitute K’eq: G' RT ln K'eq At 25 °C, in log10, rearranged for K’eq: K'eq 10 G' / 5.69 This means that a 10-fold change in Keq is equivalent to 5.69 kJ/mol difference in energy Reaction equilibria Keq Energy (G) A B If [B] = 10 [A] = 1 Then ΔG = 5.69kJ/moll A [B] Keq [A] 5.69 kJ/mol B Reaction coordinates Reaction equilibria Keq Energy (G) A B If [B] = 100 [A] = 1 Then ΔG = 11.38 kJ/moll A 11.38 kJ/mol [B] Keq [A] B Reaction coordinates Catalysis • Enzymes cannot change equilibrium of reaction • ΔG is independent of reaction pathway • Enzymes accelerate rate of reaction K+1 Keq A B A K-1 B K 1 Keq K1 Catalysis K+1 A K-1 B K 1 10 1000 Keq K1 1 100 No enzyme Equilibrium is same but rate is 100x greater + enzyme Enzymes accelerate reaction rates Reaction reaches equilibrium much quicker with enzyme catalysis Why do exergonic reactions (those with –ΔG) not take place spontaneously? Activation energy • Reactions go via a high energy intermediate • This reduces the rate at which equilibrium is reached • The larger the activation energy the slower the rate Transition state theory Transition state, S‡ Energy (G) ΔG‡ A ΔG B Reaction coordinates Transition state theory • Enzymes reduces the activation barrier • Transition state energy becomes smaller Transition state theory • The rate of reaction depends on ΔG‡ • Big ΔG‡ slow reaction • Small ΔG‡ faster reaction • Enzymes works by reducing ΔG‡ • Enzymes stabilise the transition state Summary • Enzymes are biological catalysts • Enzymes are highly specific • Enzymes increase reaction rates but do not alter the equilibrium of reactions • Enzymes stabilise transition states, reducing activation energy and increasing the rate of reaction Learning Objectives Lecture 9 • You should be able to able to define the terms Enzyme, Specificity and Co-factor • You will understand the concept of Gibbs Free Energy and its relation to reaction equilibrium • You will be able to describe how enzymes effect the rate of biological reactions and be able to define the term Activation energy in the context of Transition state theory Lecture 10 Enzymes Kinetics SBS017 Basic Biochemistry Dr. Jim Sullivan j.a.sullivan@qmul.ac.uk Learning objectives Lecture 10 • You should be able to describe the evidence for enzyme/substrate complexes • You will be able to define the terms Active sites and Active site residues • You should be able to describe the Michaelis-Menten model for enzyme kinetics and the significance of KM and Vmax Enzyme-Substrate (ES) complexes • Most enzymes are highly selective in binding of their substrates • Substrates bind to specific region of enzyme called Active Site • Catalytic specificity depends on binding specificity • Activity of many enzymes regulated at this stage Evidence for ES complexes i. Saturation effect: At constant enzyme concentration reaction rate increases with substrate until Vmax is reached. Vmax is rate (or velocity) at which all enzyme active sites are filled. Evidence for ES complexes ii. Structural data: Crystallography (3D structures), shows substrates bound to enzymes Cytochrome P450 (green) bound to its substrate camphor Evidence for ES complexes iii. Spectroscopic data: Absorption and fluorescence of proteins and cofactors change when mixed together Changes in fluorescence intensity in the enzyme tryptophan synthetase after addition of substrates Active sites • The active site of enzyme is region that binds the substrate • The catalytic groups are the amino acid side chains in the active site associated with the making and/or breaking of chemical bonds Active sites i. The active site is a 3D structure formed by groups that can come from distant residues in the enzyme (tertiary structure) A. 3D structure of Lysozyme, active site residues coloured B. Linear schematic of Lysozyme amino acid primary sequence, active site residues coloured Active sites ii. The active site takes up only a small volume of the enzyme iii. Active sites are unique chemical microenvironments, usually formed from cleft or crevice in enzyme. Active sites Active sites often exclude water, and non-polar nature of site can enhance binding of substrates and allows polar catalytic groups to acquire special properties required for catalysis Active sites iv. Active sites bind substrates with weak interactions Bonds can be electrostatic, hydrogen bonds, Van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions. ES complexes have equilibrium constants (Keq) on the 10-2 to 10-8 range, equivalent to -3 to -12 kcalmol-1 Active sites v. The specificity of an enzyme for its substrate(s) is critically dependent on the arrangement of amino acid residues at the active site Remember importance of tertiary structure Lock and key model • Proposed by Emil Fischer in 1890 Induced fit model • Substrates and enzymes are not rigid but dynamic and flexible • Daniel Koshland in 1958 proposed the induced fit model • In induced fit model the enzyme changes shape in order to optimise its fit to the substrate only after the substrate has bound Induced fit model Reaction kinetics First order reaction (uni-molecular): A K P Rate of reaction is: V k[A] Units of k: s-1 Reaction kinetics Second order reaction (bi-molecular): A+B K P Rate of reaction is: V k[A][B] Units of k: M-1s-1 But if [A]>>[B] or [B]>>[A] reaction is Psuedo First Order Michaelis-Menten Model • In 1913 Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten proposed simple model to account for kinetic characteristics of enzymes • They observed that a maximal reaction velocity with saturating substrate for a fixed amount of enzyme implies a specific ES complex is a necessary intermediate in enzyme catalysis Michaelis-Menten Model • Describes the kinetic property of enzymes At a fixed concentration of enzyme increasing [substrate] increases reaction rate Initial velocity V0 for each substrate concentration is determined from the slope of the curve at the beginning of the reaction where any reverse reaction is insignificant Michaelis-Menten Model Rate of catalysis V0 varies with substrate concentration Rate is initially proportional to [S] Reaches a saturation value Vmax Michaelis-Menten kinetics E+S k+1 k-1 ES k+2 k-2 E+P An enzyme E combines with S to from an ES complex with a rate constant of K+1 In initial reaction where reverse reaction is minimal (we can effectively ignore K-2) ES complex has two possible fates: i.Dissociate to E + S with rate constant of K-1 ii.Form P with rate constant of K+2 Michaelis-Menten equation The Michaelis-Menten equation relates the rate of catalysis to the concentration of substrate. V0 Vmax Where [S] [S] K M k1 k2 KM k1 For derivation see Stryer Chapter 8 Michaelis constant KM and Vmax are measurable constants for a particular enzymic reaction Michaelis-Menten kinetics Plotting initial velocity V0 of a reaction against substrate concentration [S] produces the Michaelis-Menten curve Understanding KM k+1 E+S k-1 ES k+2 At steady-state: rate of formation of ES = rate of breakdown of ES k1[E][S] (k1 k 2 )[ES] [E ][S] (k1 k 2 ) KM [ES] k 1 E+P Significance of KM For many reactions [S] < KM V Vmax [S] X KM [S] Vmax V [S] KM Significance of KM At high [S], [S]>>KM, V is effectively independent of [S] V Vmax [S] X X K XM [S] V Vmax Significance of KM • KM for any enzyme depends on pH, temp and ionic strength • KM is equal to the concentration of substrate required for the reaction velocity to be half its maximal value when [S] = KM then V = Vmax/2 Significance of KM If k2 << k-1 then KM is equal to the dissociation constant of the ES complex E+S k+1 k-1 ES k+2 X E+P k1 kX2 [E][S] KM K ES k1 [ES] Large KM weak binding, small KM strong binding Under these conditions KM tells us the enzyme-substrate affinity Vmax • number of substrate molecules converted into product by an enzyme molecule per unit time when enzyme is fully saturated i.e [ES] = [ET], ET is total enzyme concentration Vmax k2[ET ] Catalytic power • An enzyme’s turnover is its catalytic power • The maximum number of substrate molecules converted into product by an enzyme molecule in unit time • When E is fully saturated, it is equal to the kinetic constant k2 – also known as kcat We can calculate kcat from Vmax since Vmax= k2[ET] Catalytic power E+S k+1 k-1 ES k+2 V Vmax Vmax=k2[ET] When [S] << KM E+P [S] [S] K M k2 V [ET ][S] KM i.e Rate will increase with [ET] and [S] The max value of k2/KM is called the diffusion limit The perfect enzyme • The perfect enzyme is limited by diffusion • Max possible value of k2/KM is limited by size of k+1 to between 106 and 109 M-1s-1 • In this case k+1 is effectively a measure of how often the enzyme collides with its substrate The perfect enzyme • An enzyme with a k2/KM of between 108 and 109 M1s-1 is therefore only limited by the rate of collisions and is called diffusion limited • The catalytic processes of such enzymes are considered kinetically perfect because they are not slowing the enzyme's rate • Any lower value of k2/KM suggests that the catalytic processes are slowing the rate Reactions with multiple substrates • Most biological reactions start with 2 substrates and yield 2 products A +B P+Q • Multiple substrate reactions can be classified into classes sequential reactions and double displacement (ping-pong) reactions Sequential Reactions • All substrates bind to enzyme forming ternary complex (can be ordered or random interaction) A +B P+Q E + A EA EA + B EAB EAB EPQ EPQ EP + Q EP E+P Double Displacement Reactions • Also called “ping-pong” reactions • One or more products released before all substrates bind to enzyme A +B E + A EA E’ + B E’B P+Q EA E’ + P E’B E+Q Limitations of Michealis-Menten • M-M kinetics is simple model of enzymology • Many examples of enzymes that do not follow M-M kinetics e.g. Allosteric enzymes, which consist of multiple subunits and multiple active sites, V0 shows a sigmoidal dependence on [S] Limitations of Michealis-Menten Summary • Enzymes form complexes with their substrates • Substrates bind to the active sites of enzymes • KM is the concentration of substrate required for the reaction to be half the maximum value • Vmax is the maximum rate of reaction when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate Learning objectives Lecture 10 • You should be able to describe the evidence for enzyme/substrate complexes • You will be able to define the terms Active sites and Active site residues • You should be able to describe the Michaelis-Menten model for enzyme kinetics and the significance of KM and Vmax Lecture 11 Enzyme Catalysis SBS017 Basic Biochemistry Dr. Jim Sullivan j.a.sullivan@qmul.ac.uk Learning objectives Lecture 11 • You should be able to use Lineweaver-Burk plots to calculate KM and Vmax • You will be able to describe competitive, uncompetitive and non-competitive inhibitors and how they alter enzyme kinetics • You should understand the terms Allosteric and Cooperative regulation in relation to enzymes Michaelis-Menten Reminder V Vmax [S] [S] K M V is the velocity (or rate) of reaction [S] is the substrate concentration Vmax is the maximal velocity of the reaction KM is the Michaelis contstant ([S] at Vmax/2) Michaelis-Menten Reminder Michaelis-Menton Reminder E+S k+1 k-1 ES k+2 E+P At steady state: rate of formation of ES = rate of breakdown k1[E][S] (k1 k 2 )[ES] [E][S] k1 k2 KM [ES] k 1 KM • KM is equal to the concentration of substrate required for the reaction velocity to be half the maximal value when [S] = KM then V = Vmax/2 When k2<<k-1 then KM is to the dissociation constant of the ES complex i.e. k1 X k2 [E][S] KM K ES k1 [ES] KM tells us about substrate affinity Vmax Is the number of substrate molecules converted per unit time when enzyme is fully saturated i.e [ES] = [ET] Vmax=k2[ET] Where [ET] is total enzyme concentration Lineweaver-Burk plot • Method of calculating KM and Vmax • A plot of 1/V0 against 1/[S] • Values of KM and Vmax can be obtained from gradient of line and intercept on 1/[S] axis Lineweaver-Burk plot V Vmax [S] [S] K M 1 1 KM 1 V Vmax Vmax [S] i.e. Y = c + mX (formula for straight line graph) Lineweaver-Burk plot 1/V X X 1/Vmax X slope = KM/Vmax X X -1/KM 1/S “Double reciprocal plot” Enzyme Inhibition • Inhibitors are molecules that prevent enzymes from working • Many enzymes are regulated through the action of inhibitors • Enzymes inhibitors can also act as medicinal drugs or toxins Enzyme Inhibition • Two main types of enzyme inhibition: Irreversible, the inhibitor is tightly bound to the enzyme (sometimes covalently) Reversible, inhibitor can bind and dissociate from the enzyme Enzyme Inhibitors • Competitive inhibitors bind to active site of enzyme • Reduce the effective substrate concentration Enzyme Inhibitors • Non-competitive inhibitors stop enzyme from working • Reduce the effective enzyme concentration Enzyme Inhibitors • Uncompetitive inhibitors bind only to ES complex • Cannot be overcome by adding more substrate Enzyme Inhibitors • Some enzyme inhibitors are very important medicinal drugs • Therefore understanding how inhibitors work is very important Enzyme inhibitors as drugs • Methotrexate, structural analogue of substrate for DHFR, prevents nucleotide synthesis, used to treat cancer (reversible inhibitor) • Penicillin, covalently modifies transpeptidase, inhibiting bacterial cell wall synthesis and killing bacteria (Irreversible inhibitor) Methotrexate • Substrate analog for Dihydroxyfolate reductase (DHFR) • DHFR plays important role in biosynthesis of purines and pyrimidines. Methotrexate binds to enzyme 1000 times more effciently than dihyrdofolate Significantly reduces effective substrate concentration Penicillin • Inhibits glycopeptide transpeptidase which crosslinks bacterial cell walls • Has similar structure to normal substrate, and binds at active site Glycopeptide transpeptidase • Enzyme essential for cell wall synthesis, without it no cross-linking Penicillin • Irreversibly inhibits enzyme by reacting with serine residue in active site • “suicide”-substrate, reaction kills enzyme Competitive Inhibition [E ][I] Ki [EI] Competitive Inhibition [E ][I] Ki [EI] Increasing inhibitor increases apparent KM Vmax can still be reached by adding more substrate 50 [I] app K M K M 1 K i Non-competitive Inhibition Non-competitive Inhibition Binding of molecule stops reaction, apparent Vmax is reduced app max V Vmax 1 [I]/K i No change in KM Uncompetitive Inhibition Uncompetitive Inhibition Binding of molecule to ES stops reaction, apparent Vmax and KM are reduced Both Vmax and KM lower Lineweaver-Burk plot 1/V X X 1/Vmax X slope = KM/Vmax X X -1/KM 1/S “Double reciprocal plot” Lineweaver-Burk plots and Inhibitors • Double reciprocal plots can be used to see effects of inhibitors KM same, Vmax lower Lineweaver-Burk plots and Inhibitors • Double reciprocal plots can be used to see effects of inhibitors KM higher, Vmax same Lineweaver-Burk plots and Inhibitors • Double reciprocal plots can be used to see effects of inhibitors KM and Vmax lower Transition state analogs • In 1948 Linus Pauling proposed idea that compounds which mimic the transition state of enzymic reaction should be effective inhibitors Energy (G) Transition state, S‡ ΔG‡ A ΔG B Reaction coordinates “Transition state analogs” Transition state analogs • Enzyme work by stabilising transition state • TS analogs bind tightly to active site • Very good competitive inhibitors Proline Biosynthesis Conversion of L-Proline to D-Proline requires proline racemase Reaction proceeds via TS, Pyrrole 2carboxylic acid resembles TS and is potent inhibitor Catalytic antibodies • Stabilising transition state should catalyse a reaction • Antibodies which recognise a transition state should function as catalysts Catalytic antibodies • Insertion of Fe into porphyrin ring by ferrochelatase proceeds via ‘bent’ porphyrin transition molecule. Catalytic antibodies • N-Methylmesoporphyrin, used to generate antibodies • Antibodies can catalyse ferrochelatase reaction • Antibodies catalysed reaction at 2500 times rate of uncatalysed reaction, only10-fold less efficient than enzyme Enzyme regulation • Enzymes are often regulated • Regulation can be allosteric and co-operative • In co-operative regulation binding of substrate to one binding site helps binding to other active sites • Allosteric regulation involves product inhibition, often used to control flux through metabolic pathways Allosteric regulation A a B b C c D d regulates Product X Allosteric regulation • Allosteric enzymes do not show Michaelis-Menton kinetics • Due to the presence of multiple subunits and multiple active sites • Multimeric enzymes often have sigmoidal kinetics Allosteric kinetics Hyperbolic Sigmoidal Summary • Lineweaver-Burk plots can be used to calculate KM and Vmax • Inhibitors are substances that prevent enzymes from working • Inhibitors can be competitive, uncompetitive or noncompetitive • Transition state analogues can be used as competitive inhibitors of enzymes • Enzymes needs to be regulated, regulation can be cooperative and allosteric Enzyme summary • Without enzymes biological reactions would not take place • Without inhibitors and regulation biological reactions would happen that we didn’t want Learning objectives Lecture 11 • You should be able to use Lineweaver-Burk plots to calculate KM and Vmax • You will be able to describe Competitive, Uncompetitive and Non-competitive inhibitors and how they alter enzyme kinetics • You should understand the terms Allosteric and Cooperative regulation in relation to enzymes