2014 - Magistrates Cases

advertisement

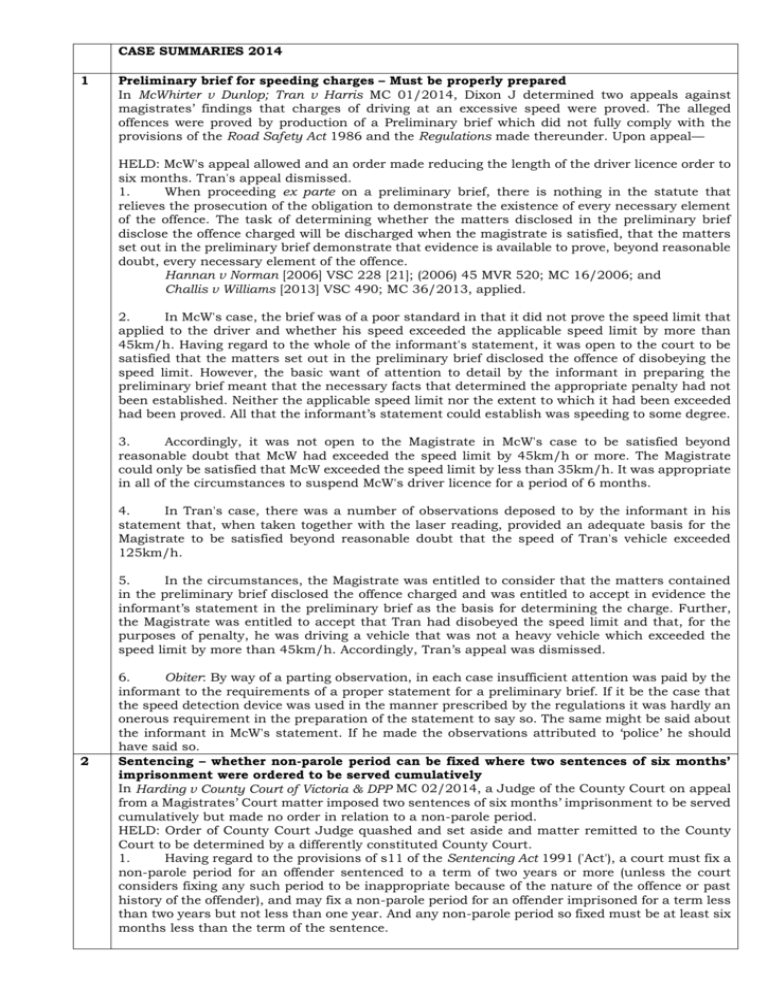

CASE SUMMARIES 2014

1

Preliminary brief for speeding charges – Must be properly prepared

In McWhirter v Dunlop; Tran v Harris MC 01/2014, Dixon J determined two appeals against

magistrates’ findings that charges of driving at an excessive speed were proved. The alleged

offences were proved by production of a Preliminary brief which did not fully comply with the

provisions of the Road Safety Act 1986 and the Regulations made thereunder. Upon appeal—

HELD: McW's appeal allowed and an order made reducing the length of the driver licence order to

six months. Tran's appeal dismissed.

1.

When proceeding ex parte on a preliminary brief, there is nothing in the statute that

relieves the prosecution of the obligation to demonstrate the existence of every necessary element

of the offence. The task of determining whether the matters disclosed in the preliminary brief

disclose the offence charged will be discharged when the magistrate is satisfied, that the matters

set out in the preliminary brief demonstrate that evidence is available to prove, beyond reasonable

doubt, every necessary element of the offence.

Hannan v Norman [2006] VSC 228 [21]; (2006) 45 MVR 520; MC 16/2006; and

Challis v Williams [2013] VSC 490; MC 36/2013, applied.

2.

In McW's case, the brief was of a poor standard in that it did not prove the speed limit that

applied to the driver and whether his speed exceeded the applicable speed limit by more than

45km/h. Having regard to the whole of the informant's statement, it was open to the court to be

satisfied that the matters set out in the preliminary brief disclosed the offence of disobeying the

speed limit. However, the basic want of attention to detail by the informant in preparing the

preliminary brief meant that the necessary facts that determined the appropriate penalty had not

been established. Neither the applicable speed limit nor the extent to which it had been exceeded

had been proved. All that the informant’s statement could establish was speeding to some degree.

3.

Accordingly, it was not open to the Magistrate in McW's case to be satisfied beyond

reasonable doubt that McW had exceeded the speed limit by 45km/h or more. The Magistrate

could only be satisfied that McW exceeded the speed limit by less than 35km/h. It was appropriate

in all of the circumstances to suspend McW's driver licence for a period of 6 months.

4.

In Tran's case, there was a number of observations deposed to by the informant in his

statement that, when taken together with the laser reading, provided an adequate basis for the

Magistrate to be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the speed of Tran's vehicle exceeded

125km/h.

5.

In the circumstances, the Magistrate was entitled to consider that the matters contained

in the preliminary brief disclosed the offence charged and was entitled to accept in evidence the

informant’s statement in the preliminary brief as the basis for determining the charge. Further,

the Magistrate was entitled to accept that Tran had disobeyed the speed limit and that, for the

purposes of penalty, he was driving a vehicle that was not a heavy vehicle which exceeded the

speed limit by more than 45km/h. Accordingly, Tran’s appeal was dismissed.

2

6.

Obiter: By way of a parting observation, in each case insufficient attention was paid by the

informant to the requirements of a proper statement for a preliminary brief. If it be the case that

the speed detection device was used in the manner prescribed by the regulations it was hardly an

onerous requirement in the preparation of the statement to say so. The same might be said about

the informant in McW's statement. If he made the observations attributed to ‘police’ he should

have said so.

Sentencing – whether non-parole period can be fixed where two sentences of six months’

imprisonment were ordered to be served cumulatively

In Harding v County Court of Victoria & DPP MC 02/2014, a Judge of the County Court on appeal

from a Magistrates’ Court matter imposed two sentences of six months’ imprisonment to be served

cumulatively but made no order in relation to a non-parole period.

HELD: Order of County Court Judge quashed and set aside and matter remitted to the County

Court to be determined by a differently constituted County Court.

1.

Having regard to the provisions of s11 of the Sentencing Act 1991 ('Act'), a court must fix a

non-parole period for an offender sentenced to a term of two years or more (unless the court

considers fixing any such period to be inappropriate because of the nature of the offence or past

history of the offender), and may fix a non-parole period for an offender imprisoned for a term less

than two years but not less than one year. And any non-parole period so fixed must be at least six

months less than the term of the sentence.

2.

In s11 of the Act, the singular expressions 'an offence' and 'a term' should be read as

including the plural of each and it deals directly with a situation where the court sentences an

offender to be imprisoned in respect of more than one offence.

3.

Upon sentencing H. to serve two terms of 6 months' imprisonment cumulative upon one

another, the judge had a discretion to fix a non-parole period of at least six months less than the

aggregate 12 month term.

Observation of Stephen J in R v Ryan [1982] HCA 30; [1982] 149 CLR 1; 40 ALR 651; 56

ALJR 422, not adopted.

4.

With real hesitation – perhaps even generously – that for reasons less to do with the judge

and more to do with the particular combination of circumstances on the day, H. did not have a

practical opportunity to be heard on the question of the fixing of a non-parole period, and was

thus denied procedural fairness.

3

5.

It would have been reasonable for H.'s counsel to expect to be warned should any need to

address the court on a non-parole period arise. The making of that reasonable assumption by his

counsel, the failure of the judge to warn counsel of the potential need to address the issue of a

non-parole period, and the consequent deprivation of an opportunity for H. (through counsel) to

make submissions on that issue, resulted in a want of procedural fairness.

Equity – Deed of Settlement entered into by parties – Two clauses found to be penalties

were voided

In Legal Practice Management (Vic) Pty Ltd (in liq) v Simms Corp Hotels & Leisure Pty Ltd & Ors MC

03/2014 a Deed of Settlement was entered into by parties to a civil proceeding whereby agreement

was made for a lesser amount to be paid by instalments. When conditions of the deed were not

complied with, the plaintiff sought reimbursement for the whole amount due. The Magistrate

dismissed the claim. Upon appealHELD: Appeal dismissed.

1.

Whether the clauses in the Deed of Settlement were void as being a penalty, it was

necessary to construe the terms and inherent circumstances judged at the time of making the

deed. When the Deed was entered into, none of the Simms parties could have been said to be liable

for the whole of the stipulated sum of $132,394.12.

Lord Dunedin in Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage and Motor Co Ltd [1914]

UKHL 1; [1915] AC 79, 86-87; 1914-15] All ER 739, followed.

2.

When read fairly, the Deed of Settlement did not contain an implied acknowledgment of

present indebtedness on the part of each of the Simms entities for the stipulated sum of

$132,394.12 as at the date of entry into the Deed of Settlement. This was not a case where it could

be said each of the Simms entities had implicitly acknowledged an existing indebtedness of a larger

sum that was quantified, and already due and owing.

Cameron v UBS AG [2000] VSCA 222; (2000) 2 VR 108; and

Calcorp (Australia) Pty Ltd v 271 Collins Pty Ltd [2010] VSCA 259; (2010) 29 VR 462,

distinguished.

Zenith Engineering Pty Ltd v Queensland Crane and Machinery Pty Ltd [2000] QCA 221;

[2001] 2 Qd R 114, followed.

3.

Under clause 1 of the Deed of Settlement, when read with clause 7, the Simms entities,

jointly and severally, agreed to pay, and the legal practice LPM agreed to accept, the Settlement

Amount of $80,000, payable by way of instalments.

4.

The Magistrate correctly found that there was no express or implied acknowledgement of

the indebtedness for the stipulated sum claimed.

4

5.

In circumstances where the relevant breach under clause 9 of the Deed was the

appointment of external administrators to one of the Simms parties, the increase in liability from

$80,000 to effectively the sum of $137,430.68, or indeed the sum of $132,394.12, constituted a

penalty, and the Magistrate was correct to dismiss the appellant’s claim.

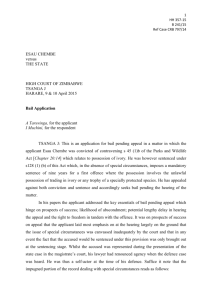

Application for bail – claim by accused that he was unable to adequately prepare his defence

in custody

In Re Application for Bail by Jan Visser (aka John Visser) MC 04/2014, Dixon J dealt with an

application for bail in respect of a serious charge. The accused stated that he was unable to

adequately prepare his defence whilst detained in custody.

HELD: Bail refused.

1.

The summary rejection by V. of the opportunity to interview prisoners was unreasonable.

2.

Accordingly, the contention advanced by V. that he was unable to prepare his defence

whilst he was in custody was not established on the facts.

Shahala v R [2012] NSWSC 351, distinguished.

3.

V. had a prior conviction for escaping from custody. He also had other relevant prior

convictions concerning an earlier attempt to escape from lawful custody in 1988 and failing to

appear in accordance with a bail undertaking in 2007. V. had an extensive criminal history in

relation to substantive criminal offences that need not be detailed. It was consistent with the

description of career criminal.

4.

Assuming that V.s capacity to prepare his defence was compromised in some way, the

Court was nonetheless satisfied that there was an unacceptable risk that if V. was released on

bail, he would fail to surrender himself into custody in answer to his bail or would commit an

offence whilst on bail.

5

5.

That conclusion required that alternative methods to facilitate communication between V.

and the potential defence witnesses be explored rather than V. being granted bail.

Application for bail – delay of more than two years – accused at risk of re-offending

In Re Application for Bail by Tyler Foxwell MC 05/2014, Dixon J heard an application for bail in

relation to a number of serious drug offences. The question of delay and personal factors of the

accused were considered in the application.

HELD: Bail refused.

1.

In relation to the substantial delay likely before the charges came on for trial, this was a

significant factor in favour of bail. Delay which has not been established as inordinate, may, in

conjunction with other factors, amount to exceptional circumstances.

Cox v R [2003] VSC 245 at [15] – [20], (Redlich J), applied.

2.

In additional to the delay, F. was a young man with no prior convictions who enjoyed the

support of his family including an offer of employment.

3.

Whilst F. could demonstrate exceptional circumstances, that of itself did not create an

entitlement to bail. Bail must be refused if there was an unacceptable risk that F. if released on

bail would do certain things such as committing further offences, endangering the safety or welfare

of members of the public or failing to surrender himself into custody to answer to bail.

DPP (Cth) v Barbaro [2009] VSCA 26; (2009) 20 VR 717; (2009) 193 A Crim R 369, applied.

4.

The Crown alleged that F. owed a large drug debt in the vicinity of $108,000 and had drug

debts owed to him of $60,000. If F. was released on bail, the Crown suggested that there was a

significant risk that activity in relation to the collection or payment of these debts could lead to F.

re-offending.

5.

F. had been assessed in relation to his drug habit, but had not received nor was about to

start carefully supervised treatment for his substance abuse problem.

6

6.

As the matters presently stood, the continued detention of F. in custody was warranted.

Bail considerations – human rights

In Woods & Ors v DPP MC 06/2014, Bell J detailed aspects of granting or refusing bail having

regard to common law rights and liberties.

1.

Everyone charged with a criminal offence is presumed to be innocent and the prosecution

must prove the guilt of the accused beyond reasonable doubt. Consistently with that presumption

and prosecutorial onus of proof, the purpose of bail is to ensure the liberty and other human rights

of persons arrested on criminal charges. In Victoria, those rights are to be found in the common

law and the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic).

2.

The provisions of the Bail Act ('Act') governing entitlement to bail and the conditions of bail

are compatible with human rights if they meet the standard of justification prescribed by s7(2) of

the Charter. It is clear that the intention of the legislature is that the provisions are to be applied,

and decision about bail are to be made, with this in mind.

3.

It is established that the bail authority must carefully consider the facts and circumstances

of the individual case and determine whether the continued detention of the accused is justified.

Reliance by the prosecution on ‘general and abstract’ considerations and a ‘stereotyped formula’,

without more, will be insufficient. Particular allegations, such that the accused would disturb

public order, must be based on facts reasonably capable of showing that kind of threat. Moreover,

generalised concerns that an accused might abscond are not regarded as sufficient justification

for refusing bail.

4.

Reference to a person’s record of prior offending is not sufficient, without more, to justify

a conclusion that he or she might re-offend. The apprehension of danger associated with reoffending must be ‘plausible’ and refusal of bail must be ‘appropriate, in the light of the

circumstances of the case and in particular the past history and the personality of the person

concerned. Lack of a fixed residence (eg homelessness) or of work or family ties are relevant but

not determinative.

5.

As can be seen from the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights and that of

Refshauge J in Seears, a fundamental requirement of human rights law in the context of bail is

that the individual facts and circumstances must be properly considered before the severe step of

depriving the accused of his or her liberty is taken.

Seears [2013] ACTSC 187, followed.

6.

Under the Bail Act, the court is required to take into account a number of matters which

always include whether the accused represents an unacceptable risk of failing to answer bail,

committing offences on bail, endangering the safety or welfare of the public or interfering with

witnesses (s4(2)(d)). Without in any way doubting the importance of the other considerations, the

primary purpose of bail is to ensure the attendance of the accused at his or her trial and the

associated preliminary hearings.

7.

In relation to exceptional circumstances, there must be something unusual or out of the

ordinary in the circumstances relied upon by the applicant before they can be characterised as

exceptional.

8.

Where an applicant has to discharge the onus of showing cause why his or her detention

was not justified, the applicant also has to answer a submission that the applicant represented

an unacceptable risk. If the prosecution discharged that onus, bail had to be refused even where

the applicant had shown cause why detention was not justified.

DPP v Harika [2001] VSC 237; and

Paterson [2006] VSC 268; (2006) 163 A Crim R 122, followed.

Re Asmar [2005] VSC 487, not followed.

9.

In relation to conditions of bail, s5(2) of the Act is one of several provisions which have

been designed to ensure that the conditions of bail (if any) impose no greater limitation upon the

liberty and human rights of the accused than the circumstances of the case require. Complying

with the obligation to consider the conditions of release in the specified order makes the court

turn its mind to the release of the accused on the least restrictive basis which is appropriate,

without preventing it from granting bail on more restrictive conditions when required by the facts

and circumstances of the case.

10.

In relation to the provision of a surety, the purpose of these provisions in the Act is to

ensure that the power to impose a condition requiring a deposit of money or a surety is exercised

in a manner which has regard to the individual means and circumstances of the accused. The

intention is that the imposition of such conditions is not to be an impediment to obtaining bail

when other conditions with which the accused could comply would achieve the same purpose.

These provisions give effect to a general principle that excessive bail shall not be required.

7

11.

In summary, the court now has explicit powers to impose particular conditions of bail when

this is required for the purposes of bail and the ancillary purpose of protecting the community.

But the authority to impose such conditions is regulated by provisions which are designed to

ensure that conditions which violate the human rights of the accused are not imposed.

Sentencing – prosecution should not be permitted to make a statement of bounds to a

sentencing judge

In Barbara & Zirilli v The Queen MC 07/2014, the High Court dealt with the question whether a

judge who refused to receive a sentencing submission from the prosecution was procedurally

unfair.

HELD: The Court: Each application for special leave granted, each appeal treated as instituted

and heard instanter but dismissed.

1.

(French CJ, Hayne, Kiefel and Bell JJ, Gageler J dissenting). The prosecution's statement

of what are the bounds of the available range of sentences is a statement of opinion. Its expression

advances no proposition of law or fact which a sentencing judge may properly take into account

in finding the relevant facts, deciding the applicable principles of law or applying those principles

to the facts to yield the sentence to be imposed. That being so, the prosecution is not required,

and should not be permitted, to make such a statement of bounds to a sentencing judge.

R v MacNeil-Brown [2008] VSCA 190; (2008) 20 VR 677; (2008) 188 A Crim R 403,

overruled.

2.

The sentencing judge's refusal to receive submissions about range did not deny the

applicants procedural fairness. It caused no other unfairness to the applicants. Each applicant

had a complete opportunity to make his plea in mitigation of sentence and, in the course of doing

so, make any relevant submission about what facts should be found for the purposes of sentencing

and what principles should be applied in determining the sentences imposed. There was no

unfairness in the sentencing judge not asking the prosecution to state an opinion about what

range of sentences could be imposed. There was no unfairness in the sentencing judge not asking

about what had been said or done in the course of discussions between the prosecution and

lawyers for the applicants before the applicants indicated their willingness to plead guilty to certain

charges. Neither the outcome of those discussions nor any hope or expectation which the

applicants may have entertained as a result was relevant to the task of the sentencing judge.

8

3.

To describe the discussions between the prosecution and lawyers for the applicants as

leading to plea agreements (or "settlement" of the matters) cannot obscure three fundamental

propositions. First, it is for the prosecution, alone, to decide what charges are to be preferred

against an accused person. Second, it is for the accused person, alone, to decide whether to plead

guilty to the charges preferred. That decision cannot be made with any foreknowledge of what

sentence will be imposed. Neither the prosecution nor the offender's advisers can do anything

more than proffer an opinion as to what might reasonably be expected to happen. Third, and of

most immediate importance in these applications, it is for the sentencing judge, alone, to decide

what sentence will be imposed.

Magistrate’s refusal to allow a party to appear by unqualified representative

In Waddington v Dandenong Magistrates’ Court & Kha MC 08/2014, The Victorian Court of Appeal

upheld a Supreme Court judge’s decision that a magistrate who refused to allow a party to appear

by an unqualified representative was not in error.

HELD: Appeal dismissed.

1.

Although s100(6) of the Act is permissive in that it affords a party a right to be represented

by a layperson in specified circumstances, it is also proscriptive inasmuch as it limits the range

of laypersons on whom it confers that right of audience ─ to laypersons empowered by law to

appear for a party.

2.

A layperson appointed under power of attorney is not thereby empowered by law to appear

for the party. In effect, s2.2.2. of the Legal Profession Act and s100(6) of the Magistrates’ Court Act

combine to produce the same result as was previously achieved by the combined operation of s111

of the Legal Profession Act 1958 and s100(6) of the Magistrates’ Court Act (except that under s111

of the Legal Profession Act, the right conferred was to appear as a solicitor or otherwise in the

circumstances provided for in s100(6)). As authority shows, that did not confer a right on a

layperson to appear on behalf of a party in any other circumstances.

Hubbard v Association of Scientologists International [1972] VicRp 37; [1972] VR 340; and

Cornall v Nagle [1995] VicRp 50; [1995] 2 VR 188, considered;

O’Toole v Scott [1965] AC 939; [1965] 2 All ER 240; (1965) 2 WLR 1160, referred to.

3.

So far from supporting the appellant W., an informed understanding of the provenance

of s100(6) of the Act showed more clearly than would otherwise be the case that s100(6) did not

authorise a layperson to appear on behalf a party except in the particular circumstances which it

identified.

4.

Even if such an appearance did not rise to the level of engaging in legal practice, that

would not have availed the appellant W. in this case. It remained that a lay advocate had no right

of audience other than was conferred by statute or in the exercise of the court’s discretion.

Accordingly, whether or not an appearance by an occasional lay advocate amounted to carrying

on practice, that kind of lay advocate’s entitlement to appear remained at the court’s discretion.

5.

There was nothing about the Magistrate's order for costs which was indicative of bias and,

although it is always a question of fact and degree whether a judicial display of bad temper or

intolerance crosses the line into the area of what is unacceptable, the law assumes that the

fictitious bystander (by reference to whose perceptions these things are meant to be judged) is

endowed with a modicum of maturity and discernment.

Ebner v Official Trustee in Bankruptcy [2000] HCA 63; (2000) 205 CLR 337; (2000) 176

ALR 644; 63 ALD 577; 75 ALJR 277; (2000) 21 Leg Rep 13, applied;

Johnson v Johnson [2000] HCA 48; (2000) 201 CLR 488; (2000) 174 ALR 655; [2000] FLC

93-041; (2000) 74 ALJR 1380; (2000) 26 Fam LR 627; (2000) 21 Leg Rep 21, referred to.

9

10

6.

Recognising as the judge did that the Magistrate had a discretion to allow the appellant

W. to appear by his lay agent, and accepting that the exercise of the discretion was informed by

and required to conform to the appellant’s common law right to a fair trial, it was not and had not

been shown that the Magistrate’s refusal to allow the appellant to appear by his lay agent denied

him a right to a fair trial or otherwise that the exercise of discretion miscarried.

Witness directed to give evidence by Audio Visual link in a committal proceeding

In Kotzmann v The Magistrates’ Court of Victoria and Anor MC 09/2014, a Magistrate gave a

direction that a witness in a committal hearing give evidence by audio visual link. Upon an

originating motion seeking judicial review of the Magistrate’s direction:

HELD: Motion denied.

1.

The Magistrate's decisions were not subject to an order in the nature of certiorari. Further,

K. had not demonstrated that the Magistrate made either a jurisdictional error or an error of law

on the face of the record. Accordingly, the proceeding had no real prospects of success and should

be disposed of summarily. Even if judicial review remedies had been available in respect of the

Magistrate's decisions, as a matter of discretion, no relief should be granted to K. because he had

availed himself of the statutory right to apply to revoke the Audio Visual Link Order.

Potter v Tural [2000] VSCA 227; (2000) 2 VR 612; (2000) 121 A Crim R 318;

Australian Broadcasting Tribunal v Bond [1990] HCA 33; (1990) 170 CLR 321; (1990) 94

ALR 11; (1990) 64 ALJR 462; 21 ALD 1; and

Craig v South Australia [1995] HCA 58; (1995) 184 CLR 163; (1995) 131 ALR 595; (1995)

69 ALJR 873; 39 ALD 193; 82 A Crim R 359, applied.

2.

The magistrate should have enquired of K. whether he had been provided with a copy of

the provisions of the Evidence (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1958 Act upon which the informant

relied in making her application and, if a copy of those provisions had not been provided, the

magistrate should have arranged for a copy to be provided. This is because those provisions

established the legal framework for the informant’s application. If it had not been possible to

provide K. with a copy of the relevant provisions, the magistrate should have taken steps to read

them to him.

Further application for bail – whether new facts or circumstances

In Re Application for Bail by Tyler Foxwell (No 2) MC 10/2014, the accused made a fourth

application for bail and was required to satisfy the court that new facts or circumstances had

arisen since the last refusal of bail.

HELD: As new facts and circumstances had arisen since the last refusal of bail, bail was fixed with

strict conditions.

1.

The primary point raised on this application was not raised on the earlier application. The

Judge did not evaluate the nature of the risk that F. might re-offend if admitted to bail by reference

to a proposal that he be immediately assessed for a drug rehabilitation program. The fact that

such an opportunity was now available was a new fact.

2.

The inability of the informant to serve the police brief of evidence in time for the April 2014

committal mention was a new circumstance that permitted the Judge to more readily infer that F.

faced a period of remand of more than two years from his arrest. However, the prospect of greater

delay did not affect the Judge's assessment of whether there was an unacceptable risk that F. may

commit further offences if admitted to bail.

3.

If released on bail, F. would be required to undergo regular urine drug screens, initially

three times a week and to see Mr Lamberti on a weekly basis for assessment, counselling,

education and relapse prevention treatment. Mr Lamberti considered the following matters to be

significant indicators that a treatment program could be beneficial for F. F. has employment

immediately available through his father’s building company. He has strong family ties and a safe

environment to live in. He will live at home with his father. He appears motivated to undertake

employment and drug treatment, an assessment that was made by Mr Lamberti after allowing for

the applicant’s motivation to secure his liberty.

11

4.

Bail fixed with strict conditions.

Towing services – operating within a certain area without authorisation

In Western Truck Towing v Douglas & Anor MC 11/2014, a tow truck operator failed to comply

with a condition in relation to a controlled area without authorisation and was fined. Upon appealHELD: Appeal dismissed.

1.

The plain meaning of s42(1) of the Act was clear. The use of the word “or” at the conclusion

of s42(1)(a) means that s42(1)(a) cannot be read conjunctively with s42(1)(b). Any other

construction is against the plain words and meaning of the section, which clearly demonstrates

the legislative intention. Section 42(1)(a) states that a tow truck with a regular licence “must not”

attend a road accident scene in a controlled area unless authorised by the allocation body for that

controlled area and given a job number for that authorisation. The section unequivocally

establishes authorisation by the allocation body as a prerequisite for a tow truck with a regular

licence to attend a road accident scene within a controlled area.

2.

The suggested construction of s42(1)(a) of the Act by the appellant in this case is against

the language of the section and the clear intention of the legislature that a tow truck with a regular

licence can only attend a road accident scene in a controlled area if authorised.

Alcan (NT) Alumina Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Territory Revenue [2009] HCA 41; (2009) 239

CLR 27; (2009) 260 ALR 1; (2009) 73 ATR 256; [2009] ATC 20-134; (2009) 83 ALJR 1152, applied.

3.

Section 42(1) of the Act cannot be construed as providing a carte blanche to the licensees

of regular tow trucks, licensed to operate outside controlled areas, to attend road accident scenes

in controlled areas, without authorisation, to tow vehicles with a GVM of four tonnes or more. Not

only is such a construction against the language of the section, it is the antithesis of the legislative

intention.

Accident Towing Advisory Committee v Combined Motor Industries Pty Ltd [1987] VicRp

48; [1987] VR 529; (1986) 6 MVR 160, applied.

4.

There is no inconsistency between Condition 2 and s42(1) of the Act. Condition 2 prohibits

attendance of the licensed tow truck at a road accident scene inside a controlled area. Section

42(1)(a) prohibits the holder of a regular tow truck licence causing such tow truck to attend a road

accident scene in a controlled area unless authorised.

12

5.

In relation to the penalty imposed by the Magistrate, the manner in which the appellant

chose to assert its “right”, by ignoring a warning that it was in breach of its Licence conditions

and that its conduct was illegal, justified the finding of the Magistrate that the conduct amounted

to a blatant attempt to undermine the regulatory scheme. Further, the assertion that the (illegal)

conduct of the appellant was undertaken because it was pursuing its interpretation of the Act

carried little weight. Such an attitude of licence holders had the potential to lead to chaotic scenes

at road accidents with the attendance of unauthorised tow trucks. It is conduct that demonstrated

a brazen disregard of the regulator and was in breach of the plain meaning of the Act and the

Licence conditions. It might be thought this conduct reduced the significance of a lack of relevant

prior convictions.

Cost consultant not admitted to practise carried out certain services

In Defteros v Scott MC 12/2014, a cost consultant who was not admitted to practise was requested

by a legal practitioner to carry out certain services. When the practitioner failed to pay the

consultant, he issued proceedings and was successful. Upon appeal:

HELD: Appeal dismissed.

1.

The question, which the magistrate was required to address, was whether the fees, claimed

by S., were in respect of work, which, contrary to s2.2.2(1) of the Act, had involved the respondent

engaging in legal practice.

2.

A determination by a court, that a person has contravened s2.2.2(1) of the Act, is a serious

finding. Such a conclusion would involve a determination by the court that the person, in this

case S., had engaged in conduct which constituted an offence punishable by imprisonment of up

to two years. In addition, such a determination would have the consequence of depriving S. of the

capacity to continue to engage in the occupation in which he worked for the last 25 years.

Accordingly, such a conclusion, by a court, would require a careful analysis of the evidence, and,

insofar as any particular factual issue was in dispute, the proof of that factual issue to the

comfortable satisfaction of the court. In essence, a conclusion, that a person had acted illegally,

as alleged by D., should not be lightly drawn on inadequate or imprecise proofs.

3.

In the present case, D. was well aware that S. had been struck off the roll of barristers and

solicitors, and that he was not, thus, representing himself as acting as a solicitor. Accordingly, the

case did not give rise to an inference by the consumer or potential consumer of S.'s services that

S. was a solicitor.

Cornall v Nagle [1995] VicRp 50; [1995] 2 VR 188, referred to.

4.

The critical question for the magistrate was whether the work performed by S., which was

the subject of the fees charged by him, was work that, although not expressly proscribed by any

particular provision in an Act or Regulation, nevertheless involved the exercise by S. of such

expertise that, in order that the public be adequately protected, it was required to be done only by

those who had the necessary training and expertise in the law.

5.

The drafting of pleadings by a legal practitioner in respect of legal proceedings involves, of

necessity, the exercise of specific legal expertise and knowledge of legal principles, both procedural

and substantive. By contrast, the preparation of a bill of costs involves, in essence, the itemisation

of work which is contained in a solicitor’s file, and the application, to those items of work, of the

prescribed scale of fees.

6.

The preparation of a bill of costs cannot be appropriately compared with the drafting of

pleadings. No doubt, the task of the preparation of a bill of costs does involve some knowledge of

the principles of the law relating to legal costs. However, in a similar way, the task of the town

planning expert, the building consultant and the tax accountant, each require an understanding

by those experts of principles of law which affect the area of work in which each of them specialise.

The fact that a consultant, in the performance of his work, applies some knowledge of legal

principles in the area of the consultant’s specialty, does not have the consequence that the

consultant is thereby engaging in legal practice. Certainly, the application of legal learning, and

in particular the application of detailed legal learning, in a particular area, might weigh in favour

of a conclusion that a consultant has engaged in legal practice. However, it is not, of itself,

sufficient to necessitate the conclusion that the particular consultant is, ipso facto, engaging in

legal practice.

13

7.

Accordingly, having regard to the evidence that was put before the Magistrate, it was open

to her Honour to conclude that she was not satisfied that, in performing the work in respect of

which he claimed fees from D., S. was engaged in legal practice. Thus, this case is not authority

in respect of the more general question whether a cost consultant is, or is not, engaging in legal

practice, contrary to s2.2.2 of the Act.

Appeal lodged in respect of a Judicial Registrar’s decision

In DPP v Bryar MC 13/2014, an appeal in respect of a Judicial Registrar’s decision was lodged

with the Magistrates’ Court out of time. When the matter came on before a Magistrate, the appeal

was rejected on the ground of double jeopardy.

HELD: Appeal allowed. Orders made by the second Magistrate quashed. Having regard to all the

factors of the proceedings, the appeal was dismissed.

1.

The matter in dispute was whether, in criminal proceedings, the police informant may seek

a review of a decision of a judicial registrar and further, whether the process was voided as a

consequence of the failure to comply with process and procedures of the Act and the Rules.

2.

The intent of the legislature in enacting s16K of the Magistrates' Court Act 1989 ('Act') was

to provide all parties, including a police informant, with a right of appeal by way of a hearing de

novo before a magistrate from a proceeding determined by a judicial registrar. The words of s16K

of the Act establish such a right “distinctly”.

3.

The underlying policy of s16K of the Act as indicated in the words of the section itself and

the statutory intention demonstrated in the Second Reading Speech is that magistrates retain

control and supervision of the Court’s jurisdiction. That necessarily means magistrates retain

control and supervision of judicial registrars. Thus, by s16K(2) of the Act, the Court of its own

motion may seek a direction for review of a decision of a judicial registrar. It is, in the end,

incomprehensible that the Parliament would establish a regime for all parties, apart from a police

informant in a criminal proceeding (of a minor nature), to seek review of a decision of a judicial

registrar, particularly in circumstances where such review, by hearing de novo, is mandatory to

the effective delegation of judicial power. There is no ambiguity in s16K of the Act and the

establishing of a review process of the decisions of judicial registrars.

4.

Such review hearing is a hearing de novo and, in such circumstances, a defence based on

a plea in bar is not available. A hearing de novo involves the exercise of the original jurisdiction

and the informant or complainant starts again and has to make out his case and call his witnesses.

5.

It was not a requirement of the Rules that the Magistrate, in making the order concerning

the review “Application Granted” specifically identified an extension of time for the granting of the

application by one day. Form 1, the form required to be used for requesting a review of the decision

of the judicial registrar, made no provision for a specific request for an extension of time as

permitted by r4 of the Rules. The Magistrate’s order of “Application Granted” was read as

encompassing the processes required by r5(4) and (5) of the Rules and incorporating an extension

of time of one day as requested in the affidavit considered by the Magistrate. The order of the

Magistrate granting the application of necessity meant the Magistrate had extended time for filing

of the request and the affidavit.

6.

In relation to the point that the request was not made by the police informant, it was not

accepted that a police prosecutor could not fill out a form and submit an affidavit on behalf of the

police informant in whose name the request was commenced, in a similar way to a solicitor filling

out such a form and swearing an affidavit in support on behalf of a client. To interpret the word

“party” in the rule as excluding a police prosecutor acting on behalf of a police informant in a

police matter was an interpretation that was overly restrictive and technical.

7.

A flexible approach to statutory preconditions is to be encouraged and an approach taken

that would overcome technical and rigid insistence upon procedural preconditions.

14

8.

Having regard to the fact that the offence, the subject of the proceeding, occurred over

three years ago and the hearing before the judicial registrar was protracted, the effluxion of time

was very significant and B. had served his penalty. Further, it was apparent that the decision of

the judicial registrar was founded on a finding of fact concerning compliance of road signage with

the traffic management plan and did not involve in any sense an institutional matter. Finally, the

important question of the construction of s16K of the Act had in effect overtaken this proceeding

at significant cost both in time and resources. In these circumstances, it was appropriate to not

refer this matter back for re-hearing.

Civil proceedings – effect of a self-executing order

In Gill v Gill MC 14/2014 a self-executing order was made which was not complied with.

HELD: Application for review dismissed.

1.

In assessing the plaintiff’s rehearing application, the Magistrate undertook the required

assessment of all of the facts and the circumstances, and concluded that the plaintiff should not

have had a right to be heard, that is, he should not have been entitled to defend the Defendant’s

claim. This was, in substance, because having failed in the first application made pursuant to

Rule 59.10(3), the plaintiff had not established any reason why the Self-Executing Order should

be set aside (other than the same reasons that had been raised on the first occasion). Thus the

effect of the orders made by the Magistrate was for the proceeding to revert to the position it was

in the moment before the entry of judgment, and because at that time the plaintiff’s defence had

been struck out, he had no standing to be heard. In those circumstances even though the plaintiff

was successful in its application, he had no right to defend or to be heard on the issue of the

quantum of the Defendant’s claim.

2.

The Self-Executing Order, once it took effect, attracted the well-established general rule

that once an order of the Court has been passed and entered or otherwise perfected in a form

which correctly expresses the intention with which it was made, then the Court which made the

order has no jurisdiction to alter it.

15

3.

The reasoning of the Magistrate in rejecting the right to be heard on the question of

quantum did not disclose error. He reasoned that, whilst it was conceivable that the judgment

entered on 9 August 2012 could be set aside and the plaintiff could be granted leave to defend the

quantum of the claim, to do that where the defence was struck out for non-compliance with orders

concerning the discovery of documents relating to that quantum, and where it was the second

application of that character, was unfair, not in the interests of justice and would undermine the

orders of the Court.

4.

The decision of the Magistrate to limit the order setting aside the judgment in the exercise

of his discretion under s110 was a reflection of the purpose of a self-executing order. The purpose

is to ensure timely compliance with the procedural requirements. The Magistrate was right not to

set aside the Self-Executing Order in the circumstances of this case because that would have

significantly undermined the utility of the Self-Executing Order, not to mention the fact that it had

already been the subject of an application to set it aside based upon substantially the same

material as was before the Magistrate for the purposes of the impugned decision.

Drink/driving – whether breath test conducted on a breath analysing instrument

In O’Connor v County Court of Victoria & Bradshaw MC 15/2014, the defendant/driver appealed

against a conviction for drink/driving. The question was whether there was sufficient evidence

that the breath test had been conducted on a defined breath analysing instrument.

HELD: Originating motion dismissed.

1.

The issue in the present case was whether the Court erred in law in holding that the

operator B. had established that the breath analysing instrument, which was used to test the

plaintiff O'C., was an instrument which met the definition of a breath analysing instrument in s3

of the Act. That is, whether the instrument in question was an Alcotest 7110 instrument and

whether the plate attached to the instrument was inscribed with the numbers 3530791.

2.

The authorities make it plain that, where notice has been given under s58(2) of the Act,

the certificate constitutes evidence of each of the facts stated in it, including facts which are

relevant to establish that the apparatus, used to test a person’s blood alcohol content, is a breath

analysing instrument as defined by s3 of the Act.

3.

In this case, the certificate contained the words “Drager Alcotest 7110”. The judge was

entitled to form the view that, by containing those words, the certificate was evidence of the fact

that the instrument, operated by B. was a “Drager Alcotest 7110”. The certificate was produced

by an apparatus, which was used by B. to test O'C's blood alcohol content by analysing a sample

of his exhaled breath. As a matter of common sense, the words “Alcotest 7110”, on that certificate,

were clearly capable, without further explanation, of denoting the type of apparatus used by B.

Accordingly, it was open to the judge on the evidence to conclude that the instrument used by the

operator in this case, was a Drager Alcotest 7110, for the purposes of the definition of a breath

analysing instrument in s3(a) of the Act.

4.

The issue, whether there was a conflict between the sworn evidence of B., and the numbers

which she read out in the conversation she had with O'C., and, if so, how that conflict should be

resolved, was entirely a matter for the judge as the tribunal of fact in the case. The evidence of the

recorded conversation did not, as a matter of law, necessitate the conclusion contended for by

O'C., namely, that the judge could not be satisfied that the label, attached to the breath analysing

instrument, was impressed with the number 3530791.

5.

It is clear that when B. read out the numbers on the instrument, she paused after reading

the numbers “51”, and then said the words “91”, as if she had read the numbers “51” in error.

This observation demonstrates that there was no necessary inconsistency or tension between the

evidence of B. and the recorded conversation.

6.

It was a matter for the judge whether there was a relevant discrepancy between the

evidence of B., and the recorded conversation, and, if so, whether that difference was required to

be explained by B. Equally, it was a matter for the judge, as the tribunal of fact to decide, whether,

in the absence of any such explanation, her Honour should draw the inference that any such

explanation given by B. would not have assisted the prosecution. The absence of any such

explanation by B. did not necessitate the conclusion that the judge could not rely on the sworn

evidence of B. as to the numbers contained on the plate affixed to the breath analysing instrument.

16

7.

Accordingly, it was open to the judge, on the evidence, to be satisfied beyond reasonable

doubt that the plate on the instrument was inscribed with the letters “3530791” and to find the

charge proved.

Speeding charge – whether evidence in preliminary brief sufficient to prove charge

In Rodger v Wojcik MC 16/2014, an ex parte speeding charge was found proved by a Judicial

Registrar and a penalty imposed. Two requirements specified in the regulations namely, that a

reading of (888) had been displayed on the radar device and that the Doppler audio signal of the

device was audible to indicate normal operation were not mentioned in the certificate or in

evidence. Upon appeal-HELD: Appeal allowed. Sentencing orders set aside. R. found guilty of exceeding the speed limit

by less than 10km/h and fined $175.

1.

There was no evidence that the radar had been used in accordance with rr46(a)(ii) and (b)

of the Road Safety (General) Regulations 2009. There was nothing in the police informant's

statement indicating either that he had ensured that a reading of (888) had been displayed when

connected to a source of electricity or that the doppler audio signal of the radar device was set at

a level clearly audible to him or that any such signal had indicated normal operation.

2.

In view of the fact that there was no evidence in the preliminary brief that the radar had

been used in accordance with rr46(a)(ii) and (b), it was not open to infer that it had been so used.

To do so would have been to speculate. While evidence is not necessarily to be understood by

reference to the maxim expressio unius est exclusio alterius, it seems that, absent other evidence,

no trier of fact acting reasonably could exclude the possibility of non-compliance with those

provisions when the informant expressly mentioned compliance with other related provisions. In

those circumstances, it was not open to the judicial registrar to act on the reading given by the

radar.

17

3.

To be sure, the judicial registrar did not in his reasons say that he found that the appellant

was travelling at 127 km/h. However, it was open to the registrar to find the charge of exceeding

the speed limit proved but it was not open for him to say by how much the speed limit was

exceeded.

Speeding charge – application for release of documents – test of legitimate forensic purpose

In Agar v McCabe MC 17/2014, the presiding Magistrate refused the defendant to a speeding

charge access to documents as to whether the relevant traffic camera was operating correctly at

the time of the alleged offence and had been sealed in accordance with the regulations.

HELD: Application for production of the subpoenaed documents dismissed. Costs order quashed.

Remitted to the Magistrates' Court to rehear and determine the costs application according to law.

1.

In relation to the decision in respect of the application, the test of legitimate forensic

purpose was one of fact and degree and allowed for differences in opinion. Although one might not

agree with it, the Magistrate’s conclusion did not defy comprehension or lack an intelligible

justification.

2.

It fell to the Magistrate to assess A.’s reliability and credibility as a witness and, it followed,

the strength of the evidence said to demonstrate the legitimate forensic purpose. There was little,

if any, evidence before the Magistrate that would not have been affected by an unfavourable

assessment of A. as a witness. As to whether the Magistrate did or should have assessed the

evidence in this way is not known, but it was open to him to do so.

3.

Even if the Magistrate had not taken an unfavourable view of A.'s evidence, there was still

the question of the probative limits of that evidence. The evidence went beyond a “mere assertion”

that A. was not speeding, but that was not the test. There was at least some merit to the opposite

conclusion – that a collection of uncorroborated assertions that a person would or could not have

been speeding added up to little more than an assertion that they were not speeding – and having

identified this possible and intelligible justification for the decision, the task of the reviewing court

was concluded.

4.

Nothing in the Magistrate’s reasons or, for that matter, the transcript was suggestive of

irrationality or illogicality or the drawing of inferences unsupported by probative material. It

followed that illogicality or irrationality could not have been inferred from the conclusion itself.

5.

The principles of proportionality and consistency ordinarily guide the judicial discretion to

award costs. Although an unfettered discretion maximises the possibility of doing justice in every

case, consistency in its exercise maintains public confidence in the legal process and is the

‘antithesis of arbitrary and capricious decision-making’. The principle that procedural costs ought

be proportionate to the dispute in question will be alive in all cases but has an additional

dimension in the criminal jurisdiction.

6.

A challenge to quantum on the basis of its alleged disproportionality or inconsistency will

only succeed where the costs order is so unreasonable or plainly unjust that the exercise of the

discretion has effectively miscarried. It followed that unless the award was so disproportionate

and/or inconsistent that it was manifestly unreasonable or plainly unjust, it will be irrelevant that

a reviewing court might form the view that the award was inconsistent or disproportionate.

7.

The costs order made by the Magistrate was severe and arguably unfair in the

circumstances. The 'on the spot' penalty for exceeding the speed limit by less than 10km/h was a

fine of around $180. If A. was convicted, the total pecuniary outcome of his criminal proceeding

including the $6,140 costs order would be disproportionate to this penalty, which was one

measure of the seriousness of the offence. Similarly, the discrepancy in costs outcomes between

cases in which private counsel are and are not briefed is obvious and introduces an element of

inconsistency to the decision.

8.

However, the costs order was not so unreasonable or plainly unjust that the Magistrate's

discretion miscarried. It was open to the Magistrate to make a costs order that did not allow seniorjunior counsel his legal fees. Proportionality and consistency are only two of the many

considerations that guide the costs discretion and provided they are taken into account, it is not

a ground of review that they might have been given excessive or inadequate weight, or that a

different conclusion on costs could or should have been reached.

9.

The Magistrate might have referred to some relevant countervailing consideration or,

equally, stated his opinion that the award was proportionate or that whilst it was disproportionate,

proportionality was only one relevant factor in the mix. It was more probable than not that a

Magistrate who was entertaining making such an award and who understood that matters going

to proportionality and consistency were relevant to the exercise of the discretion would have

spoken to the submission or invited the first defendant to comment upon it. The Magistrate did

not acknowledge the submission at all and moved seamlessly to conclude the issue adversely to

the plaintiff.

10.

It followed from the above that it was more probable than not that the Magistrate did not

turn his mind to the matters raised by the principles of proportionality and consistency.

Accordingly, the costs order was quashed and remitted to the Magistrates' Court for rehearing and

determination.

11.

It is necessary to say something about the adequacy of the Magistrate’s reasons, which

were really no more than peremptory statements of conclusion. The plaintiff A. did not press this

as a ground of review and in any event it is not clear that this failure could have constituted

18

reviewable error given the nature of the decision. It is desirable, however, that Magistrates sitting

in the Criminal Division provide at least some reasons for their decisions. These need not be

lengthy and in a case such as this might consist of no more than one or two lines. The failure to

do so frustrates the review process.

Failure to comply with condition of tow truck licence

In Western Truck Towing v Douglas & Kolonis MC 18/2014, the plaintiff company sought to appeal

from a finding of guilt in relation to a breach of the Accident Towing Services Act 2007,

HELD: Application for leave to appeal dismissed.

1.

Condition 2(a) of the licences relevantly required that a licensed tow truck should ‘be used

as a tow truck for the purpose of lifting and carrying or lifting or towing damaged or disabled motor

vehicles ... only from a road accident scene ... outside a ‘controlled area’. Four of the charges

particularised the offence as being constituted by attendance at a road accident scene within a

controlled area for the proscribed purpose.

2.

On a proper construction of Condition 2(a), the mere attendance of a tow truck at an

accident scene within a controlled area for the proscribed purpose was a breach of the condition

because what Condition 2(a) prohibited was the ‘use’ of a licensed tow truck ‘for the purpose of’

lifting and carrying damaged or disabled motor vehicles. It was a wholly inescapable inference,

from the fact of attendance of each of the applicant’s tow trucks at an accident scene for the

proscribed purpose as found by the Magistrate, that the tow truck was being ‘used’ for the

proscribed purpose.

3.

Be that as it may, the offence charged was breach of a condition of a licence. That the

particulars of four of the charges referred to the tow truck as attending at an accident scene in a

controlled area without specifically alleging that the tow truck was being used for the proscribed

purpose, although they did refer to attending for that purpose, was at best a pedantic criticism of

the particulars, but nothing of substance flowed from that criticism.

4.

Accordingly, the Magistrate did not make any error of law in finding the charges valid, nor

did the judge make any error of law on this point. At any rate, the decision in this respect was not

attended by a sufficient doubt as would warrant a grant of leave to appeal.

19

5.

The other submission of the applicant was that the effect of Condition 2 was to prohibit

the operation of the applicant’s tow trucks in a controlled area only with respect to vehicles with

a GVM of less than four tonnes. The Judge’s decision on this submission was clearly correct for

the reasons stated by his Honour. At any rate, the decision was not attended by sufficient doubt

as would warrant a grant of leave to appeal. Accordingly, leave to appeal was refused.

Whether legal cost consultant engaged in legal practice

In Defteros v Scott MC 19/2014, the Court of Appeal dealt with a case where a cost consultant

performed work on several files and sought payment. The question was whether the consultant

carried out “legal practice”.

HELD: Appeal dismissed. In relation to the question of costs on the appeal and the application for

costs of senior and junior counsel for S., certification not granted but was a matter for

determination by the Costs Court. Defteros v Scott [2014] VSC 205; MC 12/2014, approved.

1.

The critical question for the magistrate was whether the work performed by S., which was

the subject of the fees charged by him, came within the third category described by Phillips J in

Cornall v Nagle [1995] VICRP 50; [1995] 2 VR 188, namely, work that, although not expressly

proscribed by any particular provision in an Act or Regulation, nevertheless involved the exercise

by S. of such expertise that, in order that the public be adequately protected, it was required to

be done only by those who had the necessary training and expertise in the law.

2.

The only issues before the magistrate were whether the particular work which S. had done

in relation to the eight files necessarily involved engagement by him in legal practice.

3.

The work performed by S. in respect of each of those files was conducted under the

supervision of the applicant D. It was plainly open to the magistrate to decide, in those

circumstances, that on the material placed before her, D. had failed to establish that, in respect

of that work, S. was engaged in legal practice. Further, s2.2.2(1) of the Act provides that a person

must not engage in legal practice unless the person is an Australian legal practitioner. A penalty

of imprisonment for two years is imposed. In those circumstances, the magistrate was right to

require proof in the nature of that described in Briginshaw v Briginshaw [1938] HCA 34; (1938)

60 CLR 336; [1938] ALR 334; (1938) 12 ALJR 100.

4.

Obiter. What is necessary to establish in seeking to show that the conduct of an unqualified

person falls within the third category identified in Cornall v Nagle, two enquiries must be pursued:

the first enquiry will reveal the major premise in an analysis whether work performed is work for

which the public must be protected so that it is only performed by suitably qualified persons; the

second enquiry involves the minor premise: what was done in the particular case. Just because

work is done by a person with particular professional qualifications does not mean that that work

will be work for which the person must have professional qualifications. A solicitor may perform

functions that can be adequately performed by staff without professional qualifications. Not all the

work done by solicitors is work for which they require either professional qualifications or a

practising certificate. Conversely, much of the work which is done by unqualified persons in the

office of a solicitor will not involve those persons engaging in legal practice where that work is done

under the supervision of a solicitor.

5.

The first enquiry addresses the question: what work associated with legal practice should

only be done by those ‘who have the necessary training and expertise in the law’. That enquiry will

involve both empirical and evaluative considerations. The empirical considerations will involve an

analysis and description of the work which is done by solicitors; the evaluative considerations will

involve an assessment as to what parts of that work may only be done by persons admitted to

practise. The second enquiry will involve an analysis of what was done in the particular case.

6.

Because of the paucity of the evidence as to what S. did in this particular case (together

with a failure to give any evidentiary attention to the major premise), the present case was not a

suitable case to draw any wider conclusions as to the more general question whether some or all

of the work performed by costs consultants involves their engaging in legal practice contrary to

s2.2.2 of the Act.

7.

In relation to the holdings on the questions of law by the magistrate and the judge, appeal

dismissed.

20

8.

In relation to S.'s application for costs of the appeal, it was submitted that in view of the

effect that a successful appeal could have had on S., it may have been appropriate that the order

for costs included a certificate for representation of S. by both senior and junior counsel. This was

a matter for the Costs Court.

Client legal privilege/witness living overseas

In Wilson v Mitchell (No 2) MC 20/2014, an application for release of a seized file was successfully

made to a Magistrate. Upon appealHELD: Appeal allowed. The material in relation to the seized statements was not an exception to

s64(2) of the Evidence Act 2008 ('Act') and ought not to have been admitted into evidence. Remitted

to the Magistrate for rehearing.

1.

Client legal privilege is a fundamental principle of the common law. It enhances the

administration of justice by facilitating the representation of clients by their legal advisors. Clients

can only consult their lawyers with ‘freedom and candour’ within the protection afforded by the

privilege. The privilege ought not readily be set aside, and if it is to be set aside, then only on the

basis of admissible evidence.

2.

Any consideration of whether expense or delay is undue requires consideration of the

significance of the impugned asserted facts said to be proved by the representations and the nature

of the proceedings. Relevant matters include:

•

the actual cost of securing the attendance of the witness;

•

a comparison of that cost to the value of what is at stake in the litigation; and

•

an assessment of the importance of the evidence the witness might give.

Whether a delay is undue will depend not just on the delay itself but also upon what is at stake

in the litigation.

3.

On the material before him, it was not open to the Magistrate to conclude that to call the

witness would involve undue cost, delay or be reasonably impracticable. The issue at stake was

far from trivial and the witness's evidence was central to the application. The mere assertion by a

party that the witness resided in Malaysia was insufficient to establish this exception. Audio-visual

links are a fact of modern litigation. Had the police served a s67 notice of its intention to rely on

s64(2), it may well have been a simple matter to secure the witness's attendance for crossexamination via an audio-visual link.

4.

Accordingly, it followed that s64(2) of the Act was not engaged as an exception to the

hearsay rule and thus the witness's statements, on the material before the Magistrates’ Court,

ought not to have been admitted into evidence on the application.

5.

The application was remitted to the Magistrate for rehearing on the evidence that was

properly before the Magistrate.

21

Money transferred between parties; whether a loan

In Bernstone v Almack-Kelly MC 21/2014, proceedings were taken by a person who transferred

money to another. The Magistrate held that the money did not have to be repaid. Upon appealHELD: The denial of procedural fairness constituted an error of law but, having regard to the

evidence before the Magistrate, appeal dismissed.

1.

Without evidence that there was an agreement by B. to accept a loan, and an agreement

by A-K to accept the obligation to repay the loan, the Magistrate could not be satisfied that there

was a loan.

2.

Having regard to the evidence, the Magistrate failed to entertain B.'s alternative

restitutionary claim and therefore denied B. procedural fairness. It cannot be said that, had the

Magistrate heard B.'s submissions on the restitutionary claim, there could have been no difference

to the outcome of the proceeding. The denial of procedural fairness constituted an error of law.

3.

As the parties agreed that if there had been a denial of procedural fairness, the appeal

judge should decide the matter on the basis of the evidence, rather than remit the matter for

retrial.

4.

Having regard to the evidence, B. failed to establish that the payment was made upon a

mistake of fact giving rise to an obligation on A-K to make restitution. The first basis of the

restitution claim therefore failed.

5.

The question was whether A-K made out the defence of change of position. A court will not

order restitution if the defendant has acted to his or her detriment on the faith of the receipt.

22

23

6.

In making payments out of her bank account totalling $21,230, A-K changed her position

on the faith of the receipt. That change of position was made on the assumption that she was

entitled to deal with the receipt in that manner. Having regard to the Magistrate’s credit findings,

that A-K's account was truthful: that she believed in good faith that she was entitled to deal with

the receipt and that the receipt was not subject to the obligation to repay it pursuant to a loan

agreement, A-K was not under any obligation to make restitution.

Accident Compensation – whether worker entitled to payments

In Cetel Communications Pty Ltd v Parker MC 22/2014, a Magistrate held that an insurer did not

have to pay a worker weekly payments of compensation. Upon appealHELD: Appeal allowed, the Magistrate's judgment set aside and the complaint dismissed.

The magistrate erred in construing ss114(1A) and 114(2A) of the Act by not holding that s114(1A)

of the Act does not limit the application of subs (2A) to circumstances where the worker is receiving

weekly payments at the relevant date. Consequently, the Magistrate erred in law by holding on the

basis only that the worker was not in receipt of weekly payments as at 9 May 2012 that Allianz

did not have power to determine pursuant to s114(2A) not to pay the worker compensation in the

form of weekly payments from that date.

Costs in a proceeding where matters to be considered.

In Agar v McCabe & Anor (No 2) MC 23/2014, the principles to be considered by a Court were

spelled out.

HELD: No order for costs made.

1.

Costs are in the discretion of the Court. Although that discretion is effectively unfettered,

there are limits on its exercise in the sense that it must be exercised judicially. The central

principle that guides the discretion is one of doing justice to the parties in the circumstances of

each case. The usual, though by no means unyielding, rule is that costs will follow the event.

2.

As both parties had some success, courts often make orders that reflect the parties’ relative

success and failure. In the circumstances of this case, the parties’ relative successes and failures

would be best represented by making no order as to costs. The practical effect of this will be that

each party will bear their own costs of this appeal.

3.

In terms of complexity, the parties' cases were more or less evenly matched. Having regard

to the principles of consistency and proportionality, if costs were awarded, the total pecuniary

outcome of the plaintiff’s criminal proceeding would be disproportionate to the seriousness of the

alleged offending, one measure of which was the on-the-spot penalty of approximately $180.

24

4.

And as an instance of proportionality, although the first defendant was commendably

represented by senior and junior counsel, this was not a case that required two counsel.

Sentencing – factors to be considered where a cumulation order made

In Saleem v R MC 24/2014, the Court of Appeal considered the relevant factors where a sentencing

order was made in cumulation of the main sentence.

HELD: The appeal against the sentence of 14 months' imprisonment for attempting to pervert the

course of justice refused. The appeal in respect of the cumulation orders allowed and the sentence

reduced.

25

The order for cumulation produced an overall sentence that insufficiently reflected the dictates of

totality. The main offence was committed so as to try to avoid some of the sentencing ramifications

and there were a number of mitigatory matters which bore on the question of the degree to which

the cumulation was to be ordered.

Contract – loan agreement – Natural Justice

In Fato v Regione Calabria Pty Ltd MC 25/2014, a claim for payment of a loan was heard by a

Magistrate. During the hearing, the Magistrate interrupted counsel, cross-examined a witness and

expressed views on the evidence during the course of the proceeding.

HELD: Appeal allowed in relation to the issue of the order for the amount of interest payable. In

relation to the other matters, the Magistrate's factual and legal findings on the ultimate issues in

dispute were open to him. In relation to the complaint about the Magistrate's behaviour, in the

context of the trial as a whole, F. was not denied natural justice and the trial did not miscarry.

1.

The ultimate issues for the Magistrate were whether there was a binding loan agreement

for $35,000 between F. and the respondent and whether F. had breached that agreement. There

was sufficient evidence to enable the Magistrate to resolve these issues in favour of the respondent.

2.

It was not in dispute in the proceeding that, if there was a valid loan agreement between

the respondent and F. containing the terms alleged by the respondent, F. had not complied with

those terms. In other words, while the existence of a loan agreement was in issue, it was not in

dispute that F. had not made any payments of principal or interest pursuant to any such

agreement.

3.

Accordingly, F.'s ground of appeal that the Magistrate made findings of fact for which there

was no evidence, or insufficient evidence to support them could not be sustained.

4.

In relation to F.'s ground of appeal that the claim was statute barred, the Magistrate found

as a fact that the contractual obligation was varied to extend the time for the first payment of

interest. It followed that the proceeding which was commenced in October 2011 was not statute

barred.

5.

The third ground of appeal was that F. was denied natural justice in that the Magistrate

called for evidence, unreasonably interrupted counsel, cross-examined a witness and expressed

views on the evidence during the course of the proceeding.

6.

The conduct of a judicial officer during the trial of a civil action may cause a mistrial for a

number of reasons. Two reasons which were presently relevant were where the conduct gave rise

to a reasonable apprehension of bias and where the conduct involved such excessive interference

with a party’s running of his or her case that it deprived that party of a trial according to law.

7.

Procedural fairness is directed at the fairness of the decision-making process rather than

fairness of outcome, and includes a judicial obligation to afford a party a reasonable opportunity

to present or meet a case. The introduction by a trial judge of material not yet in evidence may

render a hearing unfair in the relevant sense, particularly when the material does not form part

of the case to be presented by the party affected.

8.

The Magistrate’s behaviour transgressed the limits of legitimate judicial involvement in the

conduct of a trial. However, when the trial was considered as a whole, F. failed to make out the

first limb of her natural justice and mistrial ground of appeal. The Magistrate's questions did not

have any material impact on the manner in which F.'s trial counsel conducted her case. Nor did

the Magistrate's excessive interference in the conduct of the trial deprive F. of natural justice or a

trial according to law that a new trial was warranted in the interests of justice.

9.

The second reason for rejecting the second limb of the natural justice ground of appeal was

that, even if the Magistrate’s behaviour denied F. natural justice, her trial counsel was fully aware

of that behaviour and did not raise any objection with the Magistrate in relation to it. There was

no complaint about any aspect of the Magistrate’s behaviour during the proceeding. Indeed, in

respect of some of the matters about which F. now complains, her trial counsel appeared to

acquiesce in the Magistrate’s conduct.

10.

It followed that if, contrary to the appeal judge's conclusion, the Magistrate did breach the

rules of natural justice in relation to F., her failure to object to any such breach during the hearing

constituted a waiver of the right to rely on such breach in the appeal.

26

11.

Although the third ground of appeal was rejected, it was necessary to place on record that

if the Magistrate had exercised more self-restraint and behaved more discreetly, the third ground

of appeal would not have arisen. The Magistrate’s behaviour prolonged the trial, would have given

rise to a sense of grievance on the part of both parties and added to the grounds of appeal. His

Honour was facetious and sarcastic in a tense proceeding involving family acrimony and serious

allegations of fraud when he should have been cautious and tactful. The Magistrate would have

done well to heed the wisdom and good sense of the legal principles referred to.

Claim in conversion – whether claimant owned property in dispute

In Taylor v Schaub MC 26/2104, T’s premises were bought by S which included certain goods in

the house. T. claimed ownership of the goods and sought their return or damages. The Magistrate

dismissed the claim.