Nontariff Trade Barriers and the New Protectionism

advertisement

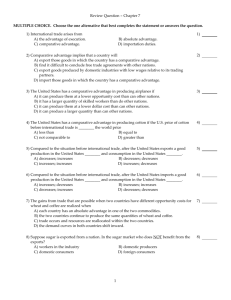

Chapter Nine: Nontariff Trade Barriers and the New Protectionism Voluntary Export Restraint Agreements by Product and Country in 1994 Industry U.S. EU Canada Total Textiles Agriculture Steel Footwear Electronics Automobiles Machine tools Other 13 2 -1 2 1 2 5 10 11 10 7 3 1 1 3 3 1 -2 -1 --- 26 14 10 10 5 3 3 8 Total 26 46 7 79 ________________________________________________________________ Source: General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), Trade Policy Review (Geneva, various issues). The Pervasiveness of Nontariff Barriers in Small Developed Nations 1996 ____________________________________________________________________________ Percent of Tariff Lines Affected __________________________________________________ Product Australia New Zealand Norway Switzerland Food, beverage and tobacco Textiles and apparel Wood and wood products Paper and paper products Chemicals, petroleum products Non-metallic mineral products Basic metal industries Fabricated metal products Other manufacturing 6.2 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.8 1.2 0.0 0.3 0.0 0.6 2.1 0.0 0.0 1.4 0.7 0.0 0.3 0.2 0.0 14.6 0.0 0.0 1.7 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.3 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Average manufacturing 0.7 0.8 3.0 0.2 _______________________________________________________________________________ Source: WTO, Market Access: Unfinished Business (WTO: Geneva, 2001), p. 21. Economic Effects of Simulatneously Removing All U.S. Import Restraints in 1999 Employment Output Sector Imports (in millions of dollars) Exports Price (percent) Textile and clothing of which: Apparel Fabric -154,950 -70,030 -32,950 -16,515 -9,443 -2,556 13,950 12,361 120 -2,038 -1,219 -240 -10.8 -17.1 -2.2 Agricultural sectors Of which: Sugar Cotton -5,130 -2,350 -2,700 -1,369 -743 -387 765 434 -9 -44 -11 -31 -3.2 -5.8 -0.1 Maritime Transportation -6,200 -1,237 1,502 155 -0.6 Shipbuilding -3,100 -390 -7 -26 0.4 High Tariff Sectors Of which: Footwear Frozen fruits & veg. -5,230 -1,340 -1,530 -828 -188 -341 1,687 984 309 -68 -7 -31 -2.9 -6.8 -0.9 Total Import-competing sectors -176,601 -20,339 17,897 -4,447 -9.1 Rest of the Economy: Agriculture and food Mining Construction Durable manufactures Non-durable manufactures Finance, insurance & real estate Transport. & communications Wholesale and retail trade Other services 2,210 1,710 6,970 46,690 10,910 12,000 10,060 32,010 69,330 47 421 140 9,189 1,368 1,312 406 514 1,320 -131 -171 nts -3,161 817 -60 -541 nts -139 159 20 nts 2,188 205 75 165 240 182 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 14,617 -3,386 3,234 0.4 Total Rest of the Economy 191,890 Total Entire Economy 17,280 -5,722 -14,511 1,213 -3.6 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Table: Welfare Gain in the United States by Removing All Significant Import Restraints in 1999_______________ Welfare Gain Sector (millions dollars) Textiles and apparel Marine transport Sugar Dairy Footwear Frozen fruits, juices & vegetables Ball and roller bearings Watches, clocks and parts Table and kitchenware Costume jewelry Ceramic wall and floor tiles $13,040 656 420 109 109 11 10 10 5 3 3 Total 14,376 ___________________________________________________ Source: OECD, Market Access: Unfinished Business (OECD: Paris, 2001), p. 17. 9.2 Import Quotas A Quota is the most important nontariff trade barrier. Definition: it is a direct quantitative restriction on the amount of a commodity allowed to be imported or exported. A. Effects of an Import Quota Import quotas have been used by industrial countries to protect their agriculture and by developing countries to stimulate import substitution of manufactured products and for balance-of-payments reasons. In Fig. 9-1, with free trade at PX= $1, the nation consumes 70X (AB), of which 10X (AC) produced domestically and the remainder 60X (CB) imported. An import quota of 30X (JH) raises price to PX= $2, exactly as with a 100% ad valorem import tariff. Reason: only at PX= $2 does the quantity demanded of 50X (GH) equals 20X (GJ) produced domestically plus the 30X (JH) allowed by the import quota. Thus, consumption reduced by 20X (BN) and domestic production increased by 10X (CM). If the government auctioned off import licenses to highest bidder, revenue effect would be $30 (JHNM). FIGURE 9-1 Partial Equilibrium Effects of an Import Quota. With an upward shift of DX to D/X: 1. With quota of 30X (J/H/): Domestic price rises to PX= $2.5 Domestic production rises to 25X (G/J/) Domestic consumption rises to 55X (G/H/). 2. With a 100% import tariff: Price remains unchanged at PX= $2 Domestic production unchanged at 20X (GJ) Domestic consumption rises to 65X (GK) Imports rise to 45X (JK). B. Comparison of an Import Quota to an Import Tariff 1. With a given import quota, an increase in demand will result in a higher domestic price and greater domestic production than with an equivalent import tariff. However, with a given import tariff, an increase in demand will leave the domestic price and domestic production unchanged but will result in higher consumption and imports than with an equivalent import quota. 2. The quota involves the distribution of import licenses. The government does not auction off these licenses in a competitive market, firms that receive them will reap monopoly profits. These profits will make potential importers devote efforts to lobbying and even bribing to obtain the licenses (rent seeking activities). Thus import quotas not only replace market mechanism but also result in waste from the point of view of the economy as a whole and contain the seeds of corruption. 3. An import quota limits imports to the specified level with certainty, while a tariff’s effect is uncertain. The reason is that the elasticity of supply and demand often unknown, making it difficult to estimate the import tariff required to restrict imports to a desired level. Furthermore, foreign exporters may absorb all or part of the tariff by increasing their efficiency or accepting lower profits. Exporters cannot do this with an import quota since quantity of imports is clearly specified. For this reason domestic producers prefer quotas to tariffs. However, since quotas more restrictive than tariffs, society should resist these efforts. 9.3 Other Nontariff Barriers and the New Protectionism Recently, nontariff trade barriers (NTBs), or new protectionism, have become more important than tariffs as obstructions to the flow of international trade and represents a major threat to the world trading system. A. Voluntary Export Restraints (VERs) They refer to the case where an importing country induces another nation to reduce its exports of a commodity “voluntarily”, under the threat of higher all-round trade restrictions, when these exports threaten an entire domestic industry. The VERs were used by developed countries against other countries (e.g. Japan, Korea) to curtail exports of textiles, steel, automobiles. These industries faced sharp declines in employment in the industrial countries. The VERs have allowed developed nations to save at least the appearance of continued support for the principle of free trade. The Uruguay Round required the phasing out of all VERs by the end of 1999 and the prohibition on the imposition of new VERs. VERs have same effect of quotas, except they are administered by the exporting country and rents are captured by foreign exporters. Examples: 1. US restraints on Japanese cars exports in 1981. 2. US restraints on steel exports in 1982 that limited imports to 20% of the US steel market. VERs are less effective than quotas and exporters tend to fill their quota with higher-quality and higher priced units of the product over time. As a rule, only major suppliers were involved, leaving the door open for other nations to replace part of the exports of the major suppliers and also from transshipments through third countries. B. Technical, Administrative, and Other Regulations These include: Safety regulations: for automobiles and electronics Health regulations: for hygienic production and packaging of imported food products Labeling requirements: showing origin and contents While many regulations serve legitimate purposes, some thinly veiled disguises for restricting imports. Other restrictions have resulted from laws requiring governments to buy from domestic suppliers. C. International Cartels An international cartel is an organization of suppliers of a commodity located in different nations that agrees to restrict output and exports of the commodity with the aim of maximizing profits. Examples: 1. OPEC: a cartel of major oil countries which restricts production and exports of oil. 2. International Air Transport Association: a cartel of major airlines that set international fares and policies Cartels are more successful with fewer members producing an essential commodity with no close substitutes. Cartels are less successful if there is a large number of international suppliers and if there are good substitutes for the commodity. This explains the failure of, or inability to set up, international cartels in minerals other than petroleum and tin, and agricultural products other than sugar, coffee, cocoa, and rubber. Cartel behaves as a monopolist in maximizing profits Since the power of a cartel lies in its ability to restrict output, there is an incentive for any one supplier to remain outside the cartel or to cheat on it by unrestricted sales at slightly below the cartel price. Example: high oil prices in the 1980s stimulated supply by nonmembers and reduced prices sharply. D. Dumping Definition: is the export of a commodity at below cost or at least the sale of a commodity at a lower price abroad than domestically. Dumping is classified as either: 1) Persistent Dumping (or international price discrimination): is the continuous tendency of a domestic monopolist to maximize total profits by selling the commodity at a higher price in the domestic market (which is insulted by transportation costs and trade barriers) than internationally (where it must meet the competition of foreign producers). 2) Predatory Dumping: is the temporary sale of a commodity at below cost or at a lower price abroad in order to drive foreign producers out of business, after which prices are raised to take advantage of the newly acquired monopoly power abroad. 3) Sporadic Dumping: is the occasional sale of a commodity at below cost or at below price abroad than domestically in order to unload an unforeseen and temporary surplus of the commodity without having to reduce domestic prices. Trade restriction to counteract predatory dumping are justified to protect domestic industries from unfair competition from abroad. These restrictions usually take the form of antidumping duties to offset price differentials, or the threat to impose such duties. Domestic producers demand protection against any type of dumping, so they discourage imports and increase their own production and profits (rents). Examples: Japan was accused of dumping steel and TV sets in the US, while European nations were accused from dumping cars, steel and agricultural products. When dumping is proved, the violating nation or firm usually choose to raise prices rather than face dumping duties. E. Export Subsidies Definition: they are direct payments (or the granting of tax relief and subsidized loans) to the nation’s exporters or potential exporters and/or low–interest loans to foreign buyers to stimulate the nation’s exports. Export subsidies can be regarded as a form of dumping. Although export subsidies are illegal by international agreement, many nations provide them in disguised (hidden) and not-so-disguised forms. Examples: o All major industrial nations give foreign buyers of the nation’s export low-interest loans to finance the purchase through agencies such as the US ExportImport Bank. o The US “extraterritorial income” or Foreign Sales Corporations provisions of the US tax code have been used by US corporations to set up overseas subsidiaries to enjoy partial exemption from US tax laws on income earned from exporters. Countervailing duties are often imposed on imports to offset export subsidies by foreign governments. Fig. 9-2 shows the effect of export subsidies on the domestic market of a small nation. At the free trade price of PX= $3.50, production is 35X (A/C/), consumption is 20X (A/B/), and exports 15X (B/C/). With a subsidy of $0.5 (equal to ad valorem=16.7%) on each unit exported, PX rises to $4.00 for domestic producers and consumers. At PX= $4, production rises to 40X (G/J/), consumption falls to 10X (G/H/), and exports rise to 30X (H/J/). Consumers lose $7.5 (a/+b/), producers gain $18.75 (a/+b/+c/), and government subsidy is $15 (b/+c/+d/). FIGURE 9-2 Partial Equilibrium Effect of an Export Subsidy. Note that area d/ is not part of the gain in producer surplus because it represents the rising domestic cost of producing more units of commodity X. Nation 2 incurs protection cost or deadweight loss of $3.75 (B / H / N / =b / = $2.5 and C / J / M / =d / = $1.25) Since producers gain less than the sum of the loss of consumers and the cost of the subsidy to taxpayers; Q: Why would Nation 2 subsidize exports? A: producers may successfully lobby for the subsidy or the government may want to promote industry X. Note that foreign consumers gain because they receive 30X instead of 15X.