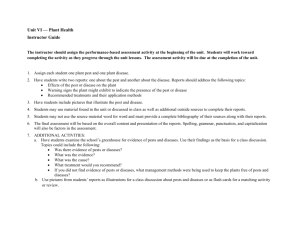

1. Introduction

advertisement