Overview of Social Epidemiology

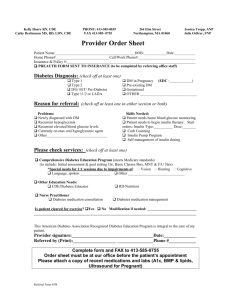

advertisement

Introduction to Social Epidemiology Illustration via a case study: Type 2 Diabetes The prevalence of diabetes varies widely among people, apparently both according to race and living circumstances: • People of European origin – – – – In Britain 2% Germany 2% Australia 8% USA 8% • Native Americans – Chilean Mapuche 1% – US Hispanic 17% – US Pima 50% • People in New Guinea – Rural 0% – Urban 37% • Aboriginal Australians – Traditional 0% – Westernized 23% • Black Africans – Rural Tanzania 1% – Urban S. Africa 8% – United States 13% Source: Jared Diamond. Nature 2003;423:599 WHY? Type 2 non-insulin dependent diabetes • Etiologically heterogeneous; common feature is high blood glucose due to altered insulin secretion and insulin resistance • Patients still produce insulin but are unable to respond effectively to it • Patients are typically obese • Often a disease of socioeconomic disadvantage. Genes and Diabetes • Several genes implicated; presumably these must have conferred a survival advantage at some time • For example, the hypothesized ‘thrifty gene’ enables a person carrying it to use food efficiently in times of plenty in preparation for famine conditions. (JV Neel. Am J Human Genet 1962;14:353-362) • Perhaps this may be relevant to diabetes? Genes interacting with lifestyle? 1. Diabetes involves genetic factors and lifestyle, especially diet 2. Symptoms disappear under conditions of starvation (e.g., siege of Paris, 1870) 3. Migrant populations see increases (immigrants to Israel; Japanese moving to USA); perhaps their diet changes when they migrate? 4. Rates fluctuate with economic conditions 5. = Lifestyle disorder seen in genetically susceptible populations; environmental factors associated with lifestyle unmask the disease. The counter-arguments 1. 30 years of searching have not identified a culprit gene 2. Obesity and Type 2 diabetes are responses to late 20th century lifestyles, so it’s really a socialenvironmental issue 3. There is also a rival hypothesis of intra-uterine exposure to hyperglycemia that has been supported in cohort studies 4. Or, alternatively, hypothesis of early childhood under-nutrition (see McDermott, Soc Sci Med 1998;47:1189-95) Some remaining questions… 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Explanations are not merely scientific; they lead to blame and action. Do we blame individuals for their unhealthy diet, or do we blame their cultural heritage, or capitalism for its marketing practices, or governments, or scientists, or … ? Will advances in bench science remove the need to worry about the social context of illness? What are the social implications of the current emphasis on searching for genetic explanations? More broadly, are the causes of individual cases the same as the causes of incidence rates? (I.e., is it the same factor that explains why one individual is diabetic, that also explains racial differences?) So, should we view a population as just an aggregation of individuals, or is it somehow different? Ways of thinking about disease Susser’s Eras in Epidemiology Paradigm Era Analytic approach Prevention Sanitary Miasma theory Clustering of mortality Sanitation Infectious disease Germ theory Laboratory Vaccination Chronic disease Black box Risk ratios Host, agent, environment EcoSystems epidemiology theory (?) Determinants Contextual to at many molecular levels Source: M. Susser. Am J Public Health 1996;86:674-7. Life-course human development view • Health is a consequence of multiple deficits • Health is an interaction between living context and bio-behavioral regulatory systems • Personal health trajectories reflect the effect of many exposures; these cumulate over time • The timing and sequence of the events is important – there are periods of enhanced susceptibility – E.g., the weathering hypothesis: cumulative exposure to stressors leads to vulnerability Things the social epidemiologist typically worries about • Biological determinism, represented in the human genome project; perception that we are largely controlled by our genes • Social Darwinism; sociobiology • Implicit reductionistic & deterministic stance; narrow focus on pathogenesis • Treatment or early detection rather than primordial prevention • Denial of the agency of people and communities Reactions to uncertainty • There is much we do not understand. DL Weed (1988) described three reactions to scientific uncertainty: – Belief (“retreat to commitment”). Implies cessation of enquiry. Characteristic of the religious right – Statistics and reference to probability. This does not help us decide where to look for further evidence, or what to ignore, nor when we have arrived – Criticism. Will not make us certain, but helps to bring weaknesses to the surface • Fourth way may be to integrate disciplines; how do we do this? Conceptual Model for Social Epidemiology Starting Point: Designing Multiple Interventions Biological Processes & Overall Model Inequalities in Health Explanations & Causal Theory Sociological Explanations Biological Societal Processes Life Events PNI Coping, Vulnerability & Resistance Social Support Individual Work Behavioral Theories Stress Theories Personality