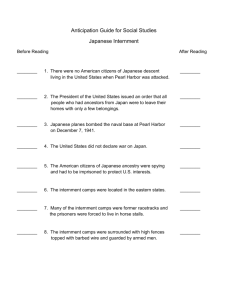

Internment during World War II

advertisement

What was wartime internment? In the interests of national security the Australian Government interned thousands of men, women and children during World War I and World War II. Most of those interned were classed as 'enemy aliens', that is, nationals of countries at war with Australia. Internees were accommodated in camps around Australia, often in remote locations. World War I During World War I, for security reasons the Australian Government pursued a comprehensive internment policy against enemy aliens living in Australia. Initially only those born in countries at war with Australia were classed as enemy aliens, but later this was expanded to include people of enemy nations who were naturalised British subjects, Australian-born descendants of migrants born in enemy nations and others who were thought to pose a threat to Australia's security. Australia interned almost 7000 people during World War I, of whom about 4500 were enemy aliens and British nationals of German ancestry already resident in Australia. > Records of WWI internment camps World War II During World War II, Australian authorities established internment camps for three reasons – to prevent residents from assisting Australia's enemies, to appease public opinion and to house overseas internees sent to Australia for the duration of the war. Unlike World War I, the initial aim of internment during the later conflict was to identify and intern those who posed a particular threat to the safety or defence of the country. As the war progressed, however, this policy changed and Japanese residents were interned en masse. In the later years of the war, Germans and Italians were also interned on the basis of nationality, particularly those living in the north of Australia. In all, just over 20 per cent of all Italians resident in Australia were interned. Australia interned about 7000 residents, including more than 1500 British nationals, during World War II. A further 8000 people were sent to Australia to be interned after being detained overseas by Australia's allies. At its peak in 1942, more than 12,000 people were interned in Australia. > Records of WWII internment camps Residents of Australia Most internees during both wars were nationals of Australia's main enemy nations already living in Australia. During World War I Germans made up the majority of internees. During World War II, as well as Germans there were also large numbers of Italian and Japanese internees. Internees also included nationals of over 30 other countries, including Finland, Hungary, Portugal and Russia. Not all internees were foreign nationals. Naturalised British subjects and those born in Australia were among those of German, Italian and Japanese origin who were interned. British-born subjects who were members of the radical nationalist organisation, the Australia First Movement, were also interned. Men made up the majority of those interned, but some women and children also spent time in the camps. Overseas internees Included in the numbers of internees accommodated in Australia were enemy aliens, mostly Germans and Japanese, from Britain, Palestine, Iran, the Straits Settlements (now Singapore and Malaysia), the Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia), New Zealand and New Caledonia. Most famous among these groups were the Germans and Italians who arrived on the Dunera from England in 1940. The overseas internees included many women and children. Prisoners of war During World War I and World War II, Australia held both internees and prisoners of war. Prisoners of war were members of enemy military forces who were captured or had surrendered, whereas internees were civilians. Most prisoners of war in Australia were sent from overseas, very few were captured in Australia. Many records do not make a clear distinction between civilian internees and military prisoners of war. The terms ‘prisoner' and ‘internee' were often used for both groups. In many cases internees and prisoners of war were accommodated in the same camps. There were differences, however, in the rights of these two groups and the way they could be treated by Australian authorities. For example, prisoners of war could be made to work while internees could not. Internees also had to be paid for any work they undertook. Camp life Internment camps were administered by the army and run along military lines. During World War I they were often referred to as concentration camps. Camps were established in repurposed institutions such as the old gaols at Berrima and Trial Bay in New South Wales. The largest camp during World War l was at Holsworthy (Liverpool), west of Sydney. During World War II, internees were first housed in prisons, such as at Long Bay gaol in New South Wales, or impromptu accommodation such as the Northam race course in Western Australia and the Keswick army barracks in Adelaide. The first camps were set up at the Enoggera (Gaythorne) and Liverpool military bases in Queensland and New South Wales and at the Dhurringile Mansion in Victoria. As the numbers of internees grew, the early camps became too small. The Australian Government then constructed purpose-built camps at Tatura (Rushworth) in Victoria, at Hay and Cowra in New South Wales, at Loveday in South Australia and at Harvey in Western Australia. Life for the internees varied between the camps, particularly between those that were temporary camps and those that were purpose-built. The conditions also depended on the geographical location of the camp, its climate, the composition of the camp population and importantly, the personality of the officer in charge. After the wars At the end of each war the internment camps were closed down. After World War I, most internees were deported. During World War II many internees, particularly Italians, were released before the end of the war. Others were allowed to leave the camps after hostilities ceased. Internees of British or European origin were permitted to remain in Australia after the war, including those who had been brought from overseas by British authorities. Most of those of Japanese origin, however, including some who were Australian-born, were ‘repatriated' to Japan in 1946. Go to content Main menu: HOME PAGE ABOUT US PRISONER OF WAR & INTERNMENT CAMPS IRRIGATION HISTORY LOCAL HISTORY EVENTS PHOTOS FROM OUR COLLECTION MUSEUM SHOP LINKS CONTACT US Download Brochure PRISONER OF WAR & INTERNMENT CAMPS World War II Camps There were 7 camps in the area during World War II which held about 4,000-8,000 people at any one time. 3 camps housed Prisoners Of War who were enemy servicemen captured in various theatres of war around the world and transported to Australia for the duration of the war. The remaining 4 camps held Internees who were civilians living in Australia or other Allied territories and countries at the outbreak of war and were deemed to be a security risk because of their nationality. The camps were situated in the Goulburn Valley as food was plentiful here and there was a good supply of water from the Waranga Basin. The camps housing Internees were: Camps 1 and 2 near Tatura for single males, mostly German and Italian Camp 3 near Rushworth for mostly German family groups Camp 4 near Rushworth for Japanese family groups Each housed approximately 1000 internees. Camp 1 had a first class hospital. In October each year the museum conducts a bus tour to the site of Camp 1 for interested people. As all the sites on which the camps were built are now in private hands,with the exception of Dhurringile Mansion which is now part of a prison, general access is not possible. Please contact the museum for details of the date and the cost of the October bus tour. Sketch of Camp 2 The camps housing POW’s were: Dhurringile Mansion: for German Officers and their batmen including Captain Detmers of HSK Kormoran Camp 13 near Murchison: or 4,000 POW’s mainly Italian and German but also some Japanese after the Cowra breakout Camp 6 near Graytown: a wood cutting camp in the bush for Italian, German and Finnish POW’s which included the crew of the Kormoran A garrison of guards and other support staff, including nurses, were stationed outside the compounds. Dhurringile Mansion is now a part of HM Prison Dhurringile and any access to the Mansion must be organised through the Victorian Department of Justice. The Tatura Historical Society members are unable to organise access for visitors to Dhurringile Mansion. The H.S.K.Kormoran Memorial at the site of Camp 13 War Cemetery The official German War Cemetery in Australia is situated next to the Tatura Cemetery. 2008 marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the war cemetery. Almost all German internees and prisoners of war who died in Australia during the war are interred in this cemetery. Those who died in the Tatura camps during the war were buried here. After the war the War Graves Commission wrote to relatives of Germans who died in other camps around Australia seeking permission to disinter their remains and bury them at Tatura in an official war cemetery. All but 17 accepted the offer and the Australian German War Cemetery in Tatura is now their resting place. The 17 whom relatives did not want disturbed are also commemorated on a wall in the cemetery. From 2010 a memorial service will be held bi-annually on the Sunday closest to November 11th. On this day the museum has an open day especially for relatives and friends who make the pilgrimage. The museum has a photo of each grave and the internment or POW details of each of the persons buried there. German War Cemetery at Tatura The Templers From 1868 onwards the families of pious Swabians, Germans from the southern region of Germany , emigrated to the Holy Land from Germany. The Holy Land at that time was Palestine which became Israel in 1948. Religious differences with the German Evangelical -Lutheran Church caused the rift which led to the founding of the Friends of Jerusalem in 1854. In 1861 the members of the Friends of Jerusalem declared themselves the "German Temple" and considered themselves an independent religious sect. They believed that they had to form a community in Jerusalem to achieve God’s plan to improve the lot of mankind. The first Templers left Germany in 1868 and by 1914 when WWI broke out there were 7 Temple Society settlements in the Holy Land. In WWI the British occupied Palestine and the Templers were interned with other German nationals in Egypt. In 1920 they were returned to their homes in the Holy Land and in 1923 Palestine came under British mandate. When WWII was declared the British authorised that the Temple colonies be surrounded by barbed wire effectively making them internment camps. In 1941 the British decided to move the internees to Australia and in August of that year they arrived in Tatura. Due to unsafe conditions in the Holy Land after the war the Templers who had been interned in Australia were offered the option of starting a new life here or returning to Germany. Templers who were still in Palestine during the war or in Germany were also able to emigrate to Australia. These Templers had friends and relatives, who died during the war, buried in the Tatura War Cemetery and began making yearly visits to commemorate their lives here. Their interest and enthusiasm led to the Tatura Historical Society’s involvement with the collection of their history, memorabilia and artefacts. Internment during World War II Camp canteen for internees, Tatura Camp 1, 1943 Source: Australian War Memorial In 1939, thousands of Australian residents like Karl Muffler suddenly found themselves identified as potential threats to Australia’s national security. The outbreak of World War II triggered a mass fear of invasion by Germany and later Japan. This led to panic that tens of thousands of Australian residents might become saboteurs or spies. Government regulations required ‘enemy aliens’ to register and limit their travel to between work and home and within a specified distance from the local post office. They had to obtain permission from the authorities to travel further or change residence. The most dramatic response was the internment in camps of many German, Italian and Japanese residents – overseas and Australian-born, and naturalised British subjects. Australia interned about 7000 residents, including nationals from over 30 other countries, such as Finland, Hungary, Portugal and Russia. A further 8000 people were sent to Australia to be interned after being detained overseas by Australia's allies. Midway through the War, more than 12,000 people – mostly men, but some women and children – were interned in 18 camps around southern Australia, including Tatura in Victoria, and Cowra and Hay in New South Wales. Internees were usually separated from their families and tried to find ways to keep themselves occupied. They set up their own study classes, theatre groups and market gardens, and were issued ‘internment currency’ in order to purchase goods within the camp grounds. Many volunteered to work on Australian farms to help with the manpower shortage and some, later in the War, joined the Australian army. Most made the best of the situation, but it was a traumatic experience that left some internees permanently scarred. Internment Camps in British Columbia Home Maps of BC Regions & Towns Accommodation Attractions Campgrounds & RVs Fishing & Guides Golf & Golf Vacations Kayaking & Canoeing Marinas Outdoor Recreation Parks & Trails Real Estate / Agents Restaurants & Pubs Sightseeing & Tours Skiing & Ski Resorts Transportation Whale Watching Wildlife Viewing Business & Shops Conference Facilities Jobs & Employment Spas & Health Weddings, Banquets Contact & Advertise Calendar of Events Discussion Forum Facts & Information Links Photo Gallery Screensavers Canada's Concentration Camps - The War Measures Act Canadian Concentration Camps By world standards Canada is a country that respects and protects its citizens' human rights. That has not always been true, however. Many people are familiar with the story of the internment of Japanese-Canadians in BC during World War II. But not many people are aware that the Japanese were not the only Canadians imprisoned during wartime simply because of their ethnic origin. The history of Canada includes more than one shameful incident in which the Canadian government used the law to violate the civil rights of its own citizens. The War Measures Act The War Measures Act was enacted on 22 August 1914, and gave the federal government full authority to do everything deemed necessary "for the security, defence, peace, order and welfare of Canada". It could be used when the government thought that Canada was about to be invaded or war would be declared, in order to mobilize all segments of society to support the war effort. The Act also gave the federal government sweeping emergency powers that allowed Cabinet to administer the war effort without accountability to Parliament, and without regard to existing legislation. It gave the government additional powers of media censorship, arrest without charge, deportation without trial, and the expropriation, control and disposal of property. This Act was always implemented via an Order in Council, rather than by approval of the democratically elected Parliament. World War I After Great Britain entered the First World War in August 1914, the government of Canada issued an Order in Council under the War Measures Act. It required the registration and in certain cases the internment of aliens of "enemy nationality". This included the more than 80,000 Canadians who were formerly citizens of the Austrian-Hungarian empire. These individuals had to register as "enemy aliens" and report to local authorities on a regular basis. Twenty-four "concentration camps" (later called "internment camps") were established across Canada, eight of them in British Columbia. View a list of World War 1 Concentration Camps. The camps were supposed to house enemy alien immigrants who had contravened regulations or who were deemed to be security threats. In fact, the "enemy aliens" could be interned if they failed to register, or failed to report monthly, or travelled without permission, or wrote to Send a Postcard Sitemap Weather in BC relatives in Austria. Other less concrete reasons given for internment included "acting in a very suspicious manner" and being "undesirable". By the middle of 1915, 4000 of the internees had been imprisoned for being "indigent" (poor and unemployed). A total of 8,579 Canadians were interned between 1914 and 1920. Over 5,000 of them were of Ukrainian descent. Germans, Poles, Italians, Bulgarians, Croatians, Turks, Serbians, Hungarians, Russians, Jews, and Romanians were also imprisoned. Of the 8,579 internees, only 2,321 could be classed as "prisoners of war" (i.e. "captured in arms or belonging to enemy reserves"); the rest were civilians. Upon each individual's arrest, whatever money and property they had was taken by the government. In the internment camps they were denied access to newspapers and their correspondence was censored. They were sometimes mistreated by the guards. One hundred and seven internees died, including several shot while trying to escape. They were forced to work on maintaining the camps, road-building, railway construction, and mining. As the need for soldiers overseas led to a shortage of workers in Canada, many of these internees were released on parole to work for private companies. The first World War ended in 1918, but the forced labour program was such a benefit to Canadian corporations that the internment was continued for two years after the end of the War. World War II During World War II the War Measures Act was used again to intern Canadians, and 26 internment camps were set up across Canada. In 1940 an Order in Council was passed that defined enemy aliens as "all persons of German or Italian racial origin who have become naturalized British subjects since September 1, 1922". (At the time, Canada didn't grant passports and citizenship on its own, so immigrants were "naturalized" by becoming British subjects.) A further Order in Council outlawed the Communist Party. Estimates suggest that some 30,000 individuals were affected by these Orders; that is, they were forced to register with the RCMP and to report to them on a monthly basis. The government interned approximately 500 Italians and over 100 communists. In New Brunswick, 711 Jews, refugees from the holocaust, were interned at the request of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill because he thought there might be spies in the group. In 1942, the government decided it wanted 2,240 acres of Indian Reserve land at Stony Point, in southwestern Ontario, to establish an advanced infantry training base. Apparently the decision to take Reserve land for the army base was made to avoid the cost and time involved in expropriating non-Aboriginal lands. The Stony Point Reserve comprised over half the Reserve territory of the Chippewas of Kettle & Stony Point. Under the Indian Act, reserve lands can only be sold by Surrender, which involves a vote by the Band membership. The Band members voted against the Surrender, however the Band realized the importance of the war effort and they were willing to lease the land to the Government. The Government rejected the offer to lease. On April 14, 1942, an Order-in-Council authorizing the appropriation of Stony Point was passed under the provisions of the War Measures Act. The military was sent in to forcibly remove the residents of Stony Point. Houses, buildings and the burial ground were bulldozed to establish Camp Ipperwash. By the terms of the Order-in-Council, the Military could use the Reserve lands at Stony Point only until the end of World War II. However, those lands have not yet been returned. The military base was closed in the early 1950's, and since then the lands have been used for cadet training, weapons training and recreational facilities for military personnel. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1942, the government passed an Order in Council authorizing the removal of "enemy aliens" within a 100-mile radius of the BC coast. On March 4, 1942 22,000 Japanese Canadians were given 24 hours to pack before being interned. They were first incarcerated in a temporary facility at Hastings Park Race Track in Vancouver. Women, children and older people were sent to internment camps in the Interior. Others were forced into road construction camps. There were also "self-supporting camps", where 1,161 internees paid to lease farms in a less restrictive environment, although they were still considered "enemy aliens". Men who complained about separation from their families or violated the curfew were sent to the "prisoner of war" camps in Ontario. The property of the Japanese Canadians - land, businesses, and other assets - were confiscated by the government and sold, and the proceeds used to pay for their internment. In 1945, the government extended the Order in Council to force the Japanese Canadians to go to Japan and lose their Canadian citizenship, or move to eastern Canada. Even though the war was over, it was illegal for Japanese Canadians to return to Vancouver until 1949. In 1988 Canada apologized for this miscarriage of justice, admitting that the actions of the government were influenced by racial discrimination. The government signed a redress agreement providing a small amount of money compensation. Could This Happen Today? The War Measures Act was repealed in 1988. It was replaced with the Emergencies Act. The Emergencies Act allows the federal government to make temporary laws in the event of a serious national emergency. The Emergencies Act differs from the War Measures Act in two important ways: 1. A declaration of an emergency by the Cabinet must be reviewed by Parliament 2. Any temporary laws made under the Act are subject to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Thus any attempt by the government to suspend the civil rights of Canadians, even in an emergency, will be subject to the "reasonable and justified" test under section 1 of the Charter. Restrictions and limitations on freedom were inevitable during times of war. To the Canadian government, internment during both World Wars was a practical solution to a perceived security problem. However the terms of the Orders in Council, and the methods used to carry them out, reveal that the government was influenced more by racial discrimination and antiimmigrant sentiments than by any real threat to national security. The stories of the internees are a reminder of how human rights are vulnerable in situations of crisis. Author: Diana Breti Copyright © 1998 The Law Connection Centre for Education, Law and Society (CELS) Simon Fraser University Vancouver, British Columbia Back to Top Web Design by Sage Internet Solutions. Copyright (c) 1998 - 2010 Shangaan Internees During the Second World War: Policy During the Second World War, enemy aliens were interned by the British authorities, in internment camps. Internees primarily consisted of enemy aliens, but during the first two years of the Second World War other aliens were also interned, including refugees who had fled Nazi Germany to escape persecution. Fears of invasion led to a general feeling of hostility towards all enemy aliens. After the outbreak of war in September 1939, known Nazi sympathisers were rounded up. This was the start of a campaign which lasted to mid-1940 by which time 8000 internees had been gathered into camps, to be deported to the Dominions. This harsh policy was gradually relaxed after the sinking of the SS Arandora Star by a German U-boat in July 1940, with the loss of 800 internees. This disaster led to vigorous protests about the British internment policy, which was changed to internment of enemy aliens in camps in Britain only. Most internees had been released by the end of 1942. Of those that remained, many were repatriated from 1943 onwards. It was not, however, until late 1945 that the last internees were finally released.