Research Paper - Matt Pugh's ePortfolio

advertisement

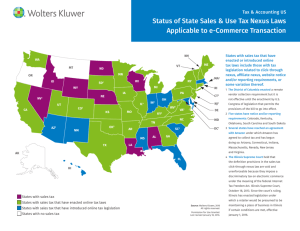

Amazon Laws Matt Pugh Professor Bailey ACCT 6991 August 1, 2014 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………2 Sales Tax and Nexus……………………………………………..2 Major Court Cases on Sales Tax…………………………………4 Public Law 86-272……………………………………………….7 Conclusion……………………………………………………….8 Bibliography……………………………………………………..9 1 Introduction Amazon.com is one of the largest electronic commerce companies in the world. Its origins and current headquarters are in Seattle, Washington, where it originally sold books in the 1990s. It wasn’t long until Amazon started selling merchandise and in the past few years moved into the area of tablets, phones, and streaming content.1 By being one of the most profitable E-commerce companies in the world, Amazon had a target on its back curtesy of numerous state governments. In a normal sales transaction a person is taxed on the purchase of tangible personal property because the purchase takes place at a physical location within state lines. The physical location requirement is synonymous with nexus. In general nexus is a constitutionally sufficient connection between a state and business.2 Nexus is the most important factor for what is commonly called “Amazon Laws.” Amazon Laws came about as a result of major litigation and law enactments. The goal of Amazon laws is to have states establish nexus within their borders even without physical presence. Two significant court cases are Bellas Hess, Inc. v. Dept. of Revenue3 and Quill Corp. v. N.D.4 and these cases provided a guideline as to whether Amazon would have to start collecting and remitting sales tax. The major law enactment was Public Law 86-272 and this provides the statutory nexus requirement for income tax purposes. Amazon argues that physical presence is the only factor for collecting and remitting taxes, where most states argue that there are supplemental activities that should cause Amazon to collect taxes. Sale Tax and Nexus Most states provide a sales tax for purchases of goods inside state lines, but with internet vendors becoming more popular, states are looking for ways to tax the sale of goods to people within their state. “The imposition of a sales tax on an out-of-state Internet vendor for sales transactions occurring with citizens of the state is unconstitutional on several levels.”5 The commerce clause 2 is the first level of constitutional practice. The commerce clause states that there must be substantial nexus or physical presence in a state for the imposition of a sales tax. If the only activity in the state is common carrier like UPS, FedEx, or the U.S. Postal Service, then that is not substantial nexus. The substantial nexus requirement is the biggest impediment for a state to tax out-of-state retailers. In Scripto, Inc. v Carson6 a Georgia retailer hired independent contractors to solicit sales in Florida. The Supreme Court held that these activities were enough to create substantial nexus in the state of Florida, thus allowing them to collect and remit sales tax. The Supreme Court said “the crucial factor governing nexus is whether the activities performed in the state on behalf of the taxpayer are significantly associated with the taxpayer’s ability to establish and maintain a market in the state for the sales.”7 They decided that maintaining a market in the state was more than just soliciting sales, they believed that keeping a steady flow of sales to the state was enough to create substantial nexus. The Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution includes a due process clause stating that a state shall not deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of the law.8 Relating this to the state’s ability to tax out-of-state retailers involves the retailer to make minimum contact with the state. The courts held that this does not always involve physical presence, but as long there was some sort of contact and the state was not trying to deter interstate commerce. The minimum contact rule is not cut and dry, but it tends to look past the sole concept of physical presence. 3 Major Court Cases on Sales Tax The first major court case in 1967 was National Bellas Hess9 in which a Missouri mail-order company was being sued by the Department of Revenue of Illinois to collect sales and use taxes from sales to purchasers inside the state. National Bellas Hess did not have any physical presence in the state, they had no telephone listing or sales agents either. The only form of contact from the state of Missouri to Illinois was through a common carrier. The state of Illinois wanted National Bellas Hess to collect and remit sales taxes to the state, but based on the commerce clause and the due process clause, that is unconstitutional. To be required to collect and remit sales taxes, there must be a minimum connection to that state. The Supreme Court held that because National Bellas Hess did not have a physical presence in the state, they would not have to collect and remit sales taxes to Illinois. The Supreme Court also pointed out that administrative responsibilities of collecting and remitting sales would be a burden on interstate commerce. As noted by the date of this case, 1967 was a long way off from common transactions we see today. The way consumers buy goods today creates a lot of complexity because the geographic location of an internet purchase is almost unrecognizable. The next major court case was Quill Corp.10 This case is very similar to the Bellas Hess case in that it is an out-of-state retailer who sells to state all around the country. Quill Corp. is a Delaware corporation with offices located in a few states throughout the United States. There is no physical presence in North Dakota nor do they have any sales agents in the state. They sell office supplies and equipment through catalogs, flyers, and telephones calls. The state of North Dakota argued that the Bellas Hess ruling is outdated because the administrative responsibilities of collecting and remitting sales tax is no longer burdensome like it was in the 1960s. They also argue that Quill Corp. distributed 24 tons of catalogs and flyers which in their minds constituted 4 an economic presence in the state of North Dakota causing a substantial nexus. In response to these arguments Quill Corp. stands by the Bellas Hess ruling and uses its lack of physical presence in the state of North Dakota to free itself from collecting and remitting sales tax. The Supreme Court rule in favor of Quill Corp. because they believe that the Bellas Hess ruling of physical presence in the state was still a good law. This is a landmark case for Amazon because with the lack of physical presence in most states, it can get away without collecting and remitting sales taxes for those states. However, as time has gone on states are finding new and innovative ways to tax internet retailers. New York was the first state to impose a sales tax on internet retailers. The most recent and most important ruling that effects Amazon and other online retailers is the New York Supreme Court11 case where the state requires online retailers to collect and remit sales tax. This is a landmark case that has motivated other states to pass legislation that will likely lead to litigation in the state and which will be appealed up to the state’s highest courts for a decision as to whether such laws will apply in those states. Amazon developed an associates program which allows website owners to link their page to Amazon.com to make sales. The associates would then be compensated based on a percentage of sales. Also along with this, they created a referral program where the associates would get referral compensation if they sign up a new enrollee. This is the basis for New York’s argument. In the associate program’s agreement, it clearly mentions that the associates are independent contractors and not employees. By looking at the data, Amazon has thousands of associates in New York and sales from New York associates to New York customers equal about 1.5% of New York sales.12 Amazon concedes that New York associates create more than $10,000 in sales. In 2008 New York signed a law stating: 5 “A person making sales of tangible personal property or services taxable under this article (“seller”) shall be presumed to be soliciting business through an independent contractor or other representative if the seller enters into an agreement with a resident of this state under which the resident, for a commission or other consideration, directly or indirectly refers potential customers, whether by a link on an internet website or otherwise”13 This Commission-Agreement Provision requires New Yorkers to collect New York taxes by out-of-state sellers if they were paid a commission. If an out-of-state seller could prove that the New York residents did not solicit any transaction, then they would be exempt from New York taxes. Amazon did not take too kindly to this new provision and commenced litigation. Amazon alleged that this was in violation of the Commerce Clause and the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. According to the Complete Auto Transit14 case a state can require businesses involved in interstate commerce to collect and remit sales taxes. As long as there is substantial nexus, it is fairly apportioned, doesn’t restrict any interstate commerce, and is equitably associated to services provided by the state, there shouldn’t be a problem. Substantial nexus can come from solicitation of sales by independent contractors, if they are on behalf of the out-ofstate business. Since Amazon pays commission to its associates, that was enough to constitute nexus in the state of New York. Whether or not they had a physical location in New York is irrelevant because they essentially hired independent contractors in the state to sell on their behalf. Lastly, Amazon alleges that it is being targeted by the New York state government. However, this is not true, in fact this law applies to all internet retailers operating inside state borders. The New York Supreme Court dismissed Amazon’s complaints and held for the New York Department of Taxation and Finance. 6 Public Law 86-272 Title 15 of the United States Code §381-384 also known as P.L. 86-272 restricts states from imposing a net income tax on income from within its borders if the activity is solely from solicitation of orders. P.L. 86-272 is split up into seven sections and codified under §381-384 under Title 15 of the U.S.C.15 Section One16 states that only tangible personal property is protected under this law. Copyrights, patents, renting, licensing, and other intangible assets are not immune from this law. Section Two17 defines solicitation as speech or conduct that invites an order. Section Three18 describes de minimis activities as activities that as a whole only establish an insignificant connection with the state. Section Four19 lists specific activities that are unprotected and protected under P.L. 86-272. The unprotected activities are ones that will cause an entity to be taxed on its net income from within state borders. Some unprotected activities include repairs and maintenance on property to be sold, collecting current or delinquent accounts, installation at or after shipment or delivery, conducting training courses, providing tech services, and much more. Some protected activities include soliciting orders by advertising, soliciting orders by in-state resident employees as long as they do not maintain an office or place of business, carrying display samples, providing cars to protected sales people, and much more. Section Five20 explains the protection of independent contractors. In this law independent contractors can solicit sales, make sales, and maintain an office and the company who hired them can still be protected from income taxation. The rules for sales tax and income are not parallel. Under P.L.86-272 solicitation of sales does not constitute an income tax but in certain states like New York, a sales tax can be imposed on an internet retailer for the same type of business activity. As long as online retailers only sell 7 tangible personal property from outside of the state and ships from outside of the state, there will not be a state income tax. This is mostly because P.L. 86-272 is a federal law that applies to the states and sales tax laws are determined by each individual state. Each individual state can create its own nexus laws and make them as stringent as legally possible. The Federal law however, is very lenient for state income tax purposes and creates an easy nexus requirement for internet retailers to get around paying state income taxes. The reason for this is because the Federal government doesn’t want to create a burden from interstate commerce. The Federal government wanted to prevent instances where minimal income was derived in a state, but yet they still had to incur the compliance cost of state tax returns which can exceed the amount of income earned. Conclusion Amazon and other large internet retailers may have had a window of sales tax collection limited to physical presence in the past, but the times have changed. Nexus has moved way past the results of the Bellas Hess and Quill cases. States like New York have passed legislation that forces collection of state sales taxes if independent contractors are hired to sell on behalf of an online retailer. Even if there is no physical presence, like an office building, New Yorkers making affiliate or click-through sales to New York residents must collect and remit sales taxes. This New York ruling has undoubtedly influenced other states to pursue their own litigation to create substantial nexus in their state with affiliate and click-through nexus. Unfortunately, not much has changed with state income tax laws. P.L. 86-272 is the law of the land and it does not allow states to tax net income if the sole activity is solicitation of sales. This is to prevent a burden of interstate commerce. The way people buy and sell products has changed immensely since the original nexus Supreme Court cases and the Amazon Laws are an outcome of changing times. 8 Bibliography Amazon.com LLC v. New York Department of Taxation and Finance. Supreme Court, 1st Judicial District (New York), ¶406-287 (2009). Letterio, Anne, A state’s way of Circumventing the Constitution: The Unconstitutional Taxation of Out-of-State Corporations that do instate business over the Internet, 22 Alb. L.J. Sci. & Tech. 411 (2012) Lunder, Erika K., and Carol A. Pettit. "Amazon Laws" and Taxation of Internet Sales: Constitutional Analysis. Rep. no. R4262*. N.p.: Congressional Research Service, 2013. Minkevitch, Hannah V., To Tax or Not to Tax? That’s Not the Question: The Role of Tax within the Maturing World of e-commerce, 27 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 705 (2012) "Overview." Amazon Media Room:. Amazon.com, June 2013. Web. 22 July 2014. <http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=176060&p=irol-mediaKit>. Sonnier, Blaise M., and M. Cathy Claiborne. "Click-Through and Affiliate Nexus Cases Subject of Recent State High Court Rulings." Taxes-The Tax Magazine (2014): n. pag. CCH Intelliconnect. Web. 8 July 2014. P.L. 86-272 Multistate Tax Commission Nexus Program Bulletin 95-1 9 1 "Overview." Amazon Media Room:. Amazon.com, June 2013. Web. 22 July 2014. <http://phx.corporateir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=176060&p=irol-mediaKit>. 2 Lunder, Erika K., and Carol A. Pettit. "Amazon Laws" and Taxation of Internet Sales: Constitutional Analysis. Rep. no. R4262*. N.p.: Congressional Research Service, 2013. 3 Bellas Hess, Inc. v. Dept. of Revenue of Illinois, SCt, 386 US 753 (1967) Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, SCt, 504 US 298 (1992) 5 Letterio, Anne, A state’s way of Circumventing the Constitution: The Unconstitutional Taxation of Out-of-State Corporations that do instate business over the Internet, 22 Alb. L.J. Sci. & Tech. 411 (2012) 4 6 Scripto, Inc. v. Carson, SCt, 362 US 207 (1960) 7 Sonnier, Blaise M., and M. Cathy Claiborne. "Click-Through and Affiliate Nexus Cases Subject of Recent State High Court Rulings." Taxes-The Tax Magazine (2014): n. pag. CCH Intelliconnect. Web. 8 July 2014. 8 Minkevitch, Hannah V., To Tax or Not to Tax? That’s Not the Question: The Role of Tax within the Maturing World of e-commerce, 27 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 705 (2012) 9 Bellas Hess, Inc. v. Dept. of Revenue of Illinois, SCt, 386 US 753 (1967) Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, SCt, 504 US 298 (1992) 11 Amazon.com, LLC v. New York State Dep’t of Taxation and Finance, 877 N.Y.S.2d 842, 846 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2009). 10 12 Amazon.com, LLC v. New York State Dep’t of Taxation and Finance, 877 N.Y.S.2d 842, 846 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2009). 13 N.Y. Tax Law § 1101(b)(8)(vi) (“Commission-Agreement Provision”) Complete Auto Transit, Inc. v Brady, 430 US 274, 279 [1977] 15 15 U.S.C. 381-384 16 P.L. 86-272(I) 17 P.L. 86-272(II) 18 P.L. 86-272(III) 19 P.L. 86-272(IV) 20 P.L. 86-272(V) 14 10