Stephanie Eckert

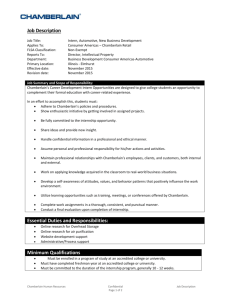

advertisement

Life of Daniel Sickles Life of Joshua Chamberlain By Stephanie Eckert How momentous were the roles of individual Union generals in the victory at Gettysburg and ultimately the defeat of the Confederate army? Both General Chamberlain and General Sickles claim to have won the crucial battle of Gettysburg for the Union army, and consequently the Civil War itself. The public immediately praised Chamberlain as a hero for his unhesitating courage and innovation on the battlefield, but scorned Sickles for disobeying military orders. Sickles fought persistently against criticisms of what he called heroism. But who was the real savior of the Union? Whose decision had the most impact, and who merits recognition as the greatest hero of Gettysburg? I will investigate the lives of these men to determine what makes a true “hero.” Portrait of the young Sickles in the prime of his military and political career from the Library of Congress Daniel Sickles was born on October 20, 1819 in New York. His father George was a Democratic lawyer and politician actively connected with the South and a supporter of Southern principles. Professor Lorenzo Da Ponte, the first professor of Italian at Columbia who led a dazzling life, became Sickles’ mentor. His relationship with the Da Pontes cultivated his for theater and opera, as well as his devoted concern with politics. Sickles led a scandalous life, and frequently engaged with prostitutes. Portrait of General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain from the Library of Congress. The battlefield as Sickles arrived at Gettysburg on July 2, 1963 boded uncertainty. He disputed the position that Meade had recommended for his men, as he had taken note of the high ground of Emmitsburg Road and saw advantages in placing his regiment at the Peach Orchard. Sickles, without orders from Meade, moved his men and left the left of the Union line exposed—one impulsive decision no one would forget. Sickles’ men faced a brutal onslaught from the Confederate army, and were unable to hold the position. “I took it on my own responsibility… I took up that line because it enabled me to hold commanding ground, which, if the enemy had been allowed to take—as they would have taken it if I had not occupied it in force—would have rendered our position on the left untenable.” Not far across the battlefield, General Chamberlain and the Twentieth Maine were stationed at Little Round Top. The first few hours of the second day of battle ran the men out of ammunition, and left a third dead or wounded. The enemy had begun to regroup, and in a moment of stunning decisiveness, he ordered that his men charge with bayonets—and they secured the sacred hill. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain’s father was a farmer and raised him out in field. He often pushed Joshua to his limits and taught him the importance of duty and honorable work. Chamberlain suffered from a lack of confidence accompanied by a speech impediment, and spent much time alone. He attended Bowdoin College, where he was very devoted to his studies. He fell in love with Fanny Adams, the minister daughter of the school’s daughter and desired to commit himself to one woman eternally. “It was imperative to strike before we were stuck… At that crisis I ordered the bayonet.” The Gettysburg Battlefield on the Third Day. Brown, L. Howell. Map of the battle-field of Gettysburg with position of troops July 2nd 1863. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891. Found on Baylor, The War of the Rebellion Atlas. “Bayonets Playing Cards Joshua Chamberlain Civil War New” on ebay. Picture from Harper’s Weekly newspaper of Daniel Sickles murdering Francis Scott Key, son of Philip Barton Key, who was having an affair with his wife Teresa. “Homicide of P Barton Key, Daniel Sickles, Washington,1859” on ebay. 2pm – Sickles moves his Third Corps men to the peach orchard 3:45pm – Meade realizes the change in Sickles’ position and artillery fire begins in the peach orchard 4:00pm—Hood’s division attacks Little Round Top 5:30pm – Confederate army captures the peach orchard 5:30pm – Chamberlain orders bayonet charge Chamberlain Figurine “Union Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain Britains #17925” on ebay These popular toy items based on Chamberlain illustrate his fame and reputation among the public as a hero. Historians think… Scholars define Sickles as a scoundrel. Historian Thomas Keneally argues that Sickles’ move at Gettysburg was made in the aftershock of the battle of Chancellorsville, where the Confederate army slaughtered Union men from a position similar to that of the Peach Orchard. Coddington and Trudeau, however, believe there was a hidden agenda behind Sickles’ disobedience at Gettysburg—Coddington suggests that he sought to expose Meade as a poor military leader, due to his personal issues with the general. Trudeau along the same vein argues that he risked the fate of an entire army in order to secure himself a seat in the White House. Historians think… Chamberlain’s career was characterized by his chivalry. His thought was centered on the Transcendentalist and European Romantic movements that glorified nature, chivalry, the individual, and bravery. He saw the war as his gateway to selfdiscovery, an honorable crusade. His romantic focus led him to embody the ideal of the Weber leadership typology of charismatic authority, as he inspired loyalty and bravery in his men. Sickles seems to fit the Big Five personality trait of neuroticism. The angry temperament and paranoia he expressed at the battle of Gettysburg led him to make a poor decision. Obituary of Joshua Chamberlain from Library of Congress Chronicling America newspaper website “1903117wr American Civil War General Daniel Sickles dead May 4, 1914 newspaper” on ebay Monument to Sickles at the location of his wounding Monument to Third Corps Monument to Third Corps These monuments at Gettysburg Military Park are all dedicated to Sickles or the Third Corps. Interesting, because Sickles funded the construction of the park and has various monuments in it. All of these photos are by RunnerJenny on flickr. Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg: The Second Day (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 93, 95, 102. Daniel Sickles in Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg: The Second Day (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 103. Thomas A. Desjardin, These Honored Dead: How the Story of Gettysburg Shaped American Memory, (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2003), 128; Pfanz, Gettysburg: The Second Day (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 234. Joshua Chamberlain in Oliver W. Norton, The Attack and Defense of Little Round Top, (New York: Neale Publishing Company, 1913), 214. Thomas Keneally, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles, (New York: Doubleday, 2002), 3-4, 7. Glenn W. LaFantasie, Gettysburg Heroes: Perfect Soldiers, Hallowed Ground (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008), 50, 52, 56. Thomas Keneally, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles (New York: Doubleday, 2002), 277, 279. Edwin B. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1968), 346-348. Noah A. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, (New York: Harper Collins, 2002), 367. Glenn W. LaFantasie, Gettysburg Heroes: Perfect Soldiers, Hallowed Ground (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008), 63, 88; Bruce Catton, Gettysburg: The Final Fury, (Garden City, NY: Doubleday 1974), 41; Jeffrey Denman, "What really happened on Little Round Top?," Civil War Times 44, no. 3: 34-40 (Military & Government Collection, 2005), EBSCOhost (accessed February 29, 2012); Max Weber, Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, Edited by Hans Gerth and Charles Mills (Psychology Press, 1991), 52. Thomas A. Desjardin, These Honored Dead: How the Story of Gettysburg Shaped American Memory, (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2003), 128. In Conclusion… But who was the real savior of the Union? Whose decision had the most impact, and who merits recognition as the greatest hero of Gettysburg? Ultimately, however advantageous the Peach Orchard could have been, Sickles did not have the manpower to utilize it successfully. He was first and foremost a politician, seeking his own ends. Chamberlain, however, was not a selfseeker. In the face of disaster he was able to collect himself and make a confident decision, shock the enemy, and protect the left that Sickles had endangered. Chamberlain was able to maintain the image of himself that he wanted the public to see successfully, while Sickles by no means garnered the praise and recognition that Chamberlain did. My research has revealed that these men’s actions on the battlefield were tightly interwoven; therefore, neither of them single-handed won the battle. My research question thus boils down to who had the most influence—whether Sickles’ men deflected a deadly Confederate attack or impeded Union victory, a question to which there is no certain answer. The conclusion I am able to draw is this—that both men were great leaders, and heroes in their own rite Many believe Little Round Top to have been the most crucial point in the battle of Gettysburg. Historian Catton argues that if Hood had taken this essential point, the Union line on Cemetery Ridge would have been hopeless and the Confederates would have won the battle. According to LaFantasie, however, “…the Chamberlain we have come to know is, in a sense, the same man Chamberlain saw in the mirror every morning.” According to Denman, Chamberlain exaggerated in his after-action reports, the creation dates of which are questionable at best. “Just here a nation torn asunder by civil war would persevere or perish, and it was all in his hands.” Monument to the 20th Maine at Gettysburg. By BattlefieldPortraits.com on Flickr.