MRSQ-PromotingLibraryResources

advertisement

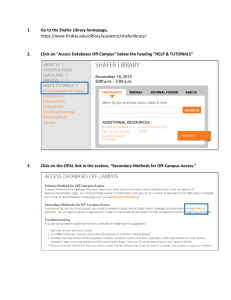

Promoting Music Library Resources -- With Mixed Results Clayton Crenshaw, Music Liaison Librarian Crouch Fine Arts Library, Baylor University ClaytonE_Crenshaw@baylor.edu This is a preprint of an article whose final and definitive form has been published in the Music Reference Services Quarterly, Volume 17, Number 4, 2014. Music Reference Services Quarterly is available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/wmus20/current. Abstract This article reports the results of efforts to promote music library resources. Selected new books and CD recordings were promoted using a service desk display. Circulation statistics for those items were compared with other new items that were not promoted. The display proved to be very effective. Two literature databases and two audio databases were also promoted using multiple methods. Usage statistics from the promotion period were then compared with those for the previous two academic years. A slight increase in use was observed for one database, while overall usage declined for the other three. Introduction As a constant stream of new materials is added to the music library, and as many thousands of dollars are spent annually on subscriptions, the desire of librarians and library staff members is to see these resources used frequently. This recalls two of Ranganathan’s Five Laws: “books are for use” and “every book its reader.” But those ideals are often not fully realized in our libraries, whether the information resources are on the shelves or online. At Baylor University’s Crouch Fine Arts Library, we saw many new items and some valuable databases getting little use, so we planned and implemented a variety of marketing activities designed to increase use and awareness. By studying the results of these initial efforts, we hope to create better plans for the future and thereby increase our marketing effectiveness. 1 Marketing is described as the combination of four groups of tools: product, price, promotion, and place.1 Our efforts were focused on promotion and place; since we were working with library resources that had already been acquired, product and price did not factor into our plans. New Items Display When new physical books and recordings are added to the Crouch Library collections, they are normally sent directly to the stacks. Faculty members and students can keep up with new arrivals on the Library’s website, but the vast majority of these new items get little use. Except for LP recordings, the media stacks are closed. The book stacks are open, but circulating items are located on the opposite side of the floor, out of sight from the service desk and main traffic areas. To promote the new items, a small display was developed using book stands and a rack for CDs, which incorporated a sign designed by the University Libraries’ Marketing and Communication office (Figure 1). The display was placed for maximum visibility: at the service desk where circulating items are checked out and returned, which is also adjacent to the Library’s main entrance. Figure 1 Service desk display of new books and CDs 2 Literature Review Though promotional displays are an infrequent topic in the library literature, Camacho, Spackman, and Cluff2 summarized more than four decades of research in this area. It consistently showed a higher level of circulation for items that are displayed prominently. In their academic library, books that were moved to discipline-specific display shelves received a 58% increase in circulation. The shelves were augmented by online lists of the recommended books. In other recent studies, Jacobson described a mobile display cart containing both books and audiovisual materials. After progressively fine-tuning the items featured to the tastes of his public library patrons, up to 90% of the items received use.3 Librarians at James Madison University achieved a dramatic increase in the circulation of a recreational reading collection, simply by turning a visual barrier into a highly visible display space. They also created thematic displays of items from the general collection, which circulated at a rate of 27%; this compared favorably to the 17% rate for the general collection as a whole.4 Methods From the new books and CDs cataloged for the Crouch Library from June 1, 2013, to April 30, 2014, 90 CDs and 24 books were selected for promotion. Excluded from the study were books with a copyright date earlier than 2010; books in the MT class that are primarily notated music; and unpublished recordings of performances on the Baylor campus. All other new books and CDs were studied. Books were typically available for check-out within one week of being cataloged, and CDs within two weeks. Those selected for promotion were put on display at the service desk. Two books were displayed at one time, along with 6-8 CDs. The rack permitted only two CDs to be visible at any one time, so they were occasionally rotated from front to back. Original dust jackets were 3 saved and used with the hardback books on display. All items were given a status of “display – available” in the library catalog, and book dummies in the stacks also directed patrons to the service desk. Items were on display for a maximum of two weeks; if they had not been checked out during that time period, they were replaced. Those that were checked out from the display area were shelved upon return and not displayed again. During the months of September–December, the promoted items were selected by the music librarian. Selection was based on two factors: musical content, intended to reflect the diverse audiences within the School of Music such as vocalists, instrumentalists, music historians, jazz musicians, etc.; and visual appeal, including aspects such as interesting graphics, engaging photos, bright colors, and clear typography. During the months of March-May, selection of promoted items was randomized. (Displays in January and February were thematic in nature and not included in the study.) By removing the element of curation, visibility then became the only factor being tested. A local accession number system is used for CD call numbers, so only those with call numbers ending in 0 or 5 were chosen for display. From a list in call number order, books were chosen sequentially by their class number (e.g., ML 410); where there was more than one with the same class number, only the first in the group was displayed. Results Circulation statistics for the promoted items were compared with those for: (1) the rest of the new items of the same format that were received during the study period but not promoted; and (2) items in a control group, drawn from the non-promoted items and having content similar to an item that was selected for promotion. Matches between recordings were based on characteristics such as composer, time period, performance forces, and musical genre, and 4 more than one of these where possible. Book matches were based on similar subject matter, such as Benjamin Britten, conducting, jazz performance, or musical theatre. Each item with circulation activity was counted only once, regardless of the number of checkouts it received during the study period. As shown in Tables 1 and 2 below, 65% of the CDs and 50% of the books selected and promoted during September-December were checked out. In the control groups for the same period, 23% of the CDs and 27% of the books were checked out. The figures for all items not promoted, including those assigned to the control groups, were 11% for CDs and 16% for books. Circulation activity was similar, but lower overall, for the March-May period when selection of the promoted items was randomized. In the promotion group, 36% of the CDs and 30% of the books were checked out. Thirteen percent of the CDs in the control group showed circulation activity. An insufficient number of content matches were found to form a control group for the books. For all items not promoted, 7% of the CDs and 16% of the books were checked out. Table 1 CDs with circulation activity Selective Display (Sept – Dec) Randomized Display (Mar – May) Promotion Group 31/51 = 65% 14/39 = 36% Control Group 9/39 = 23% 4/30 = 13% 57/534 = 11% 27/363 = 7% Selective Display (Sept – Dec) Randomized Display (Mar – May) Promotion Group 7/14 = 50% 3/10 = 30% Control Group 3/11 = 27% (no control group) 36/219 = 16% 21/134 = 16% All Not Promoted Table 2 Books with circulation activity All Not Promoted 5 Database Promotions Like most academic music libraries, the Crouch Library provides a wealth of databases for faculty and student use. They are accessible to authorized users from a homegrown directory, the library catalog, and a discovery tool. Some are underutilized despite their valuable content and the presence of a thriving music school on our campus. Four music databases were selected for promotion and study during the 2013-2014 academic year, using several different methods detailed below. Literature Review In the library literature one finds descriptions of numerous methods that are used to promote electronic resources. The written word plays a role in many of them, as expected, but personto-person methods also show up frequently. Information about the results of these efforts is sparse and sometimes lacking in detail. Thompson and Schott reported success in boosting use of library databases by redesigning a library website for easier access and promoting the new e-resources page through e-mail, flyers, library instruction sessions, and presentations to faculty members.5 In a second case study, they tied increased usage to an overhaul of the library’s instruction program. This included new instruction request forms, faculty workshops, pathfinders, and updated web pages on library instruction. Curriculum revisions and a new course requirement were also cited as factors contributing to the increases.6 Millet and Chamberlain pointed to their instruction sessions with peer-to-peer tutors as the main factor leading to greatly increased use of Academic Search Premier on the campus of Trinity University. Monthly usage statistics increased as much as five-fold over a period of five years; however, it was not clear exactly which usage metric was being compared.7 Betz et al. described a peer teaching program using graduate students to introduce the Scopus database. 6 After implementation of the program on six university campuses, searches of Scopus doubled within a five-month period.8 In another academic library, Smith reported increases in usage statistics following a variety of marketing activities that were not specific to databases.9 The increases in usage statistics were not quantified. Brannon described several database promotion activities that led to unspecified increases in use by patrons of her public library. Activities included staff training, database classes in the library, school visits, in-house ads, signs, informational cards, and distribution of imprinted pens, pencils, and magnets.10 In their 2013 book, Marketing Your Library’s Electronic Resources, Kennedy and LaGuardia concluded that “ . . . there is not enough published information yet about the marketing of eresources to be able to point to a particular strategy or grouping of techniques as best practice to attain a favorable outcome.”11 Yet there is no shortage of literature about marketing techniques used, developing marketing plans, assessing marketing plans, and even analyzing marketing plans. So why aren’t more libraries reporting the results of their carefully planned efforts? Perhaps because it is difficult or impossible to show cause-effect relationships with any certainty, since there are factors influencing the use of electronic resources that cannot be consistently captured, observed, or measured. These can be as subtle as the location of a link on a web page, or as ephemeral as a mention from a professor in the classroom. Some libraries may be reluctant to share results because the news is not good, or because they are more concerned about sustaining their marketing activities than they are about measuring results in a meaningful way. Whatever the reasons, more objective data needs to be shared so that libraries can eventually develop best practices and focus their limited resources on the techniques that hold the most promise of success. To quote Kennedy and LaGuardia again, “We firmly believe that if you can't measure it then you shouldn't do it. If you're going to be 7 accountable for your marketing efforts you have to be able to report back on how successful you've been.”12 Methods In this study, four databases were selected for promotion: Music Index; Retrospective Index to Music Periodicals (RIPM); Music Online: Classical Music Library; Naxos Music Library Jazz. Music Index and RIPM index music literature; Classical Music Library and Naxos Music Library Jazz provide access to streaming audio recordings. Use of all four was relatively low when compared to other music databases offered by the Library. Each database was promoted using two or three of the following: a sign on or near the service desk; a website ad on the Crouch Library home page; a post on the Crouch Library Facebook page; a shortcut icon on the desktop of computers in the Library’s lab. Promotional activities took place between September 2013 and May 2014. Table 3 details the methods used for each database, as well as the approximate number of weeks that each one was available for viewing. Because viewing older Facebook posts requires some effort on the part of the user, these were counted as viewable only as long as they were the most recent one on the page. 8 Table 3 Database promotions and number of weeks viewable Promoted Database Music Index RIPM Naxos Music Library Jazz Classical Music Library Signage Website Ad 12 13 17 6 9 5 - Facebook Post <1 <1 2 2 Desktop Icon 28 - Results At the end of the study period, monthly totals for user sessions were examined for changes and year-over-year comparisons were made. The sessions metric was selected for its consistency– -representing one visit by one user–-rather than searches, which can vary widely during a given session. Where possible, monthly session totals from September 2013-May 2014 were compared with the monthly totals for the two previous academic years. Usage patterns for the two literature databases, Music Index and RIPM, were similar to those for the previous years; the numbers of sessions declined slightly. This followed overall increases in sessions for both databases from 2011-2012 to 2012-2013. Figure 2 shows the monthly totals for Music Index, which were down 6% overall compared with the same months one year earlier. Figure 3 shows the monthly totals for RIPM, which were down 7% overall compared with the same months one year earlier. 9 User Sessions Per Month 500 450 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 Music Index 2011-2012 Sessions Music Index 2012-2013 Sessions Music Index 2013-2014 Sessions Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Figure 2 Monthly sessions for Music Index 450 User Sessions Per Month 400 350 300 250 RIPM 2011-2012 Sessions 200 RIPM 2012-2013 Sessions 150 RIPM 2013-2014 Sessions 100 50 0 Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Figure 3 Monthly sessions for RIPM Statistics for the streaming audio databases were less consistent. As shown in Figure 4, Naxos Music Library Jazz experienced occasional spikes in usage during the 2011-2012 and 20122013 periods. There were none of those for 2013-2014, which resulted in a 40% decline in sessions from the previous year. 10 User Sessions Per Month 70 60 50 Naxos Music Library Jazz 2011-2012 Sessions 40 30 Naxos Music Library Jazz 2012-2013 Sessions 20 Naxos Music Library Jazz 2013-2014 Sessions 10 0 Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Figure 4 Monthly sessions for Naxos Music Library Jazz In January 2014, the Crouch Library transitioned to a new platform for Classical Music Library. From that point on, unfortunately, no session data was available from the publisher. Total sessions for September-December 2013 increased 17% year-over-year, as shown in Figure 5. A check of search statistics also showed an increase overall, with higher search totals for six of the nine months in the study period. This followed a large decline in use over the previous two years. User Sessions Per Month 350 300 250 Classical Music Library 2011-2012 Sessions 200 150 Classical Music Library 2012-2013 Sessions 100 Classical Music Library 2013-2014 Sessions 50 0 Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Figure 5 Monthly sessions for Classical Music Library 11 Similar to the control groups for CDs and books, usage statistics were also examined for three other databases that have content similar to one of the promoted databases. Within this group, large swings in usage were observed in the year-over-year numbers for sessions (Table 4). Table 4 Session totals for databases not promoted RILM Abstracts of Music Literature International Index to Music Periodicals Naxos Music Library Sept 2012 May 2013 4,637 Sept 2013 May 2014 2,010 Year Over Year -2,627 2,564 10,280 7,716 301% 6,870 4,345 -2,525 -37% % Change -57% Discussion The retail-style display of new books and CDs at the service desk proved quite effective at driving use. This was particularly striking because it runs counter to a trend of declining use. Crouch Library book circulation has declined for the past two years; CD circulation has decreased in four of the last five years. While these changes in format preferences should not be ignored, our patrons’ demonstrated interest in the physical items on display is an important finding that will inform collection development decisions. A higher percentage of items in the control groups were circulated than the non-promoted items as a whole. This suggests that some uses of the promoted items can be attributed to their content alone. But the impact of promotion is clearly a larger factor, since the promoted items were circulated at a much higher rate than those in the control groups. Consistent with Jacobson’s experience, display items circulated at much higher rate when they were thoughtfully selected by a librarian. Compared to the randomly selected items, circulation rates were 20% higher for books and 29% higher for CDs. Even so, items that were selected randomly and promoted received much more use than those that were not promoted. 12 In contrast to the results for physical items, there was little evidence that the promotional activities for the targeted databases led to increased use. Quite the contrary--compared to the previous academic year, the total number of sessions declined for three of the four. Music Index and RIPM showed small decreases, while the one for Naxos Music Library Jazz was substantial. Monthly totals for those databases did not show any spikes in usage that might indicate a response to the promotions. The one bright spot was Classical Music Library, which over a four-month period showed a modest increase in sessions. The lack of data for the rest of the study period makes this result inconclusive, but the increases in both sessions and searches suggest that the promotional activities may have had a positive effect. It is perhaps important that this database was promoted mainly by means of a large, colorful poster, 22 x 28 inches, placed at the end of the service desk. The other signs used to promote databases were 8.5 x 11 inches and less interesting graphically. The Classical Music Library poster was also on view for a greater number of weeks, being used in rotation for about half of the academic year. While most of the promoted databases showed small changes in usage patterns, large changes were observed among three similar databases that were not promoted. This indicates that, beyond the Library’s promotional activities, there were other factors influencing database selection and use by our patrons. A few of the possibilities: the addition of the Summon discovery tool in August 2013; new instructors for a graduate course in music research methods; and expanded discoverability of streaming music titles in both the library catalog and the discovery tool. 13 Conclusions This study confirms the continuing value of displays in increasing circulation of featured library materials. Even a display of randomly selected items was shown to be effective. But for libraries that are able to invest more time and effort, a curated display is the way to achieve maximum impact. While most of the previous studies were focused on books alone, these results demonstrate that the technique is equally useful for media items. Future research could explore what motivates patrons to take items from the display, how they use the items, and to what extent the initial check-out generates more uses through word-of-mouth advertising. With the possible exception of the poster-size sign, the methods used to promote databases were not shown to be effective in increasing use. It must be acknowledged that some of them were inconspicuous, such as the small shortcut icon on computer desktops and the website ads on the lower half of the Library’s home page. Further research is needed to test the effectiveness of posters and other promotional methods with high visibility, such as large digital signs or website ads in a prime page location. Once consistently effective techniques can be identified, libraries can better target their efforts and avoid wasting time and money on those that elicit little response. In studying database promotions, the potential for influences outside the library cannot be avoided. Rather than relying solely on vendor usage statistics, then, triangulation of research methods is needed to increase confidence in the results. Surveys, interviews, and website log analysis are examples of additional methods that could be employed. Acknowledgment The author wishes to thank Mandi Marshall, Carl Flynn, Jason Kersten, and Darlene Youts for their assistance with this research project and Eileen Bentsen, Christina Chan-Park, and Sha Towers for reviewing the manuscript. 14 Notes 1 Philip Kotler and Gary Armstrong, Principles of Marketing, 9th ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J: Prentice Hall, 2001), 67–68. 2 Leticia Camacho, Andy Spackman, and David Cluff, “Face Out: The Effect of Book Displays on Collection Usage,” Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship 19, no. 2 (April 2014): 115–122, doi:10.1080/08963568.2014.883874. 3 Alan Jacobson, “Building Displays That Move the Merchandise,” American Libraries 43, no. 1/2 (2012): 44. 4 D. Yvonne Jones et al., “Simple Marketing Techniques and Space Planning to Increase Circulation,” Collection Management 36, no. 2 (April 4, 2011): 111–116, doi:10.1080/01462679.2011.553774. 5 Mark S. Thompson and Lynn Schott, “Marketing to Community College Users,” Serials Librarian 53, no. 3 (2007): 63–68. 6 Ibid., 68–73. 7 Michelle S. Millet and Clint Chamberlain, “Word-of-Mouth Marketing Using Peer Tutors,” Serials Librarian 53, no. 3 (2007): 98–102. 8 Brie Betz et al., “Marketing Library Database Services to End Users: Peer-to-Peer Outreach Using the Student Ambassador Program (SAm),” Serials Librarian 56, no. 1–4 (January 2009): 251, doi:10.1080/03615260802687088. 9 Debbi A. Smith, “Strategic Marketing of Library Resources and Services,” College & Undergraduate Libraries 18, no. 4 (October 2011): 340–347, doi:10.1080/10691316.2011.624937. 10 Sian Brannon, “A Successful Promotional Campaign: We Can’t Keep Quiet About Our Electronic Resources,” Serials Librarian 53, no. 3 (2007): 43–52. 11 Marie R. Kennedy and Cheryl LaGuardia, Marketing Your Library’s Electronic Resources : A How-to-DoIt Manual for Librarians, (Chicago: Neal-Schuman, 2013), 32. 12 Ibid., 38. Bibliography Betz, Brie, Stephanie Willen Brown, Deb Barberi, and Jeanne M. Langendorfer. “Marketing Library Database Services to End Users: Peer-to-Peer Outreach Using the Student Ambassador Program (SAm).” Serials Librarian 56, no. 1–4 (January 2009): 250–54. doi:10.1080/03615260802687088. Brannon, Sian. “A Successful Promotional Campaign: We Can’t Keep Quiet About Our Electronic Resources.” Serials Librarian 53, no. 3 (2007): 41–55. Camacho, Leticia, Andy Spackman, and David Cluff. “Face Out: The Effect of Book Displays on Collection Usage.” Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship 19, no. 2 (April 2014): 114–24. doi:10.1080/08963568.2014.883874. Jacobson, Alan. “Building Displays That Move the Merchandise.” American Libraries 43, no. 1/2 (2012): 42. Jones, D. Yvonne, Margarite McCandless, Kara Kiblinger, Kelly Giles, and Jenne McCabe. “Simple Marketing Techniques and Space Planning to Increase Circulation.” Collection Management 36, no. 2 (April 4, 2011): 107–18. doi:10.1080/01462679.2011.553774. Kennedy, Marie R., and Cheryl LaGuardia. Marketing Your Library’s Electronic Resources : A How-to-Do-It Manual for Librarians, 2013. 15 Kotler, Philip, and Gary Armstrong. Principles of Marketing. 9th ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Prentice Hall, 2001. Millet, Michelle S., and Clint Chamberlain. “Word-of-Mouth Marketing Using Peer Tutors.” Serials Librarian 53, no. 3 (2007): 95–105. Smith, Debbi A. “Strategic Marketing of Library Resources and Services.” College & Undergraduate Libraries 18, no. 4 (October 2011): 333–49. doi:10.1080/10691316.2011.624937. Thompson, Mark S., and Lynn Schott. “Marketing to Community College Users.” Serials Librarian 53, no. 3 (2007): 57–76. 16