HS501: 2011 Wntr, Armstrong, Early Church to Reformation

advertisement

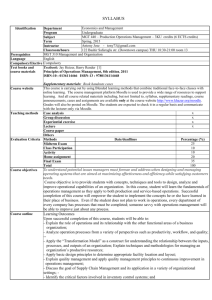

HS501: Traditional Syllabus Winter 2011, Jan 10 – Mar 21 Section 2: Tue 7 – 10:15 pm Dr. Chris Armstrong Bethel Seminary Office: Faculty Hall, A212 E-mail: c-armstrong@bethel.edu T.A.: Laine Gebhardt; geblai@bethel.edu EARLY CHURCH TO THE REFORMATION Course Description: An introduction to the major movements, persons, and ideas in Christian history from the church's birth through the fifteenth century. Students will also be introduced to basic methodology and bibliographical tools used in the study of the past. Objectives: 1. Recount major events, ideas, figures, and movements in the Church from its beginnings to the fifteenth century. 2. Analyze, discuss, and write about selected documents and ideas in church history. 3. Learn how to connect the church's past to our present in a careful, responsible, and practically helpful way. Texts: Gonzalez, Justo. The Story of Christianity, vol. 1, Early Church to Reformation. San Francisco: HarperCollins Publishers, 1984. ISBN 0060633158 Bettenson, Henry and Chris Maunder, eds. Documents of the Christian Church, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0192880713 Heath, Gordon L. Doing Church History: A User-friendly Introduction to Researching the History of Christianity (Toronto, Ont.: Clements Publishing, 2008; 1894667905) www.christianhistory.net. Currently this website is giving access to all articles from all back issues of Christian History magazine (all 99 of ‘em), for free. Where I indicate "CH" in the readings below, I'm referring to this source. Course Requirements: 1. Testing: Three unit exams will be given, each covering one segment of the course, with questions on the Gonzalez text and lectures. Short answer questions will be asked on Gonzalez and essay questions on the lectures. 1st Edition page numbers are followed by (2nd edition page numbers). Exam I Gonzalez 7-17, (8-23), 31-108 (41-125) and lecture material Exam II Gonzalez 113-219 (131-260) and lecture material Exam III Gonzalez 231-374 (269-445) and lecture material HS501: Syllabus page 2 2. Online forum postings: TO BE DESCRIBED 3. In-class discussion leading: TO BE DESCRIBED 4. Final integrative paper: TO BE DESCRIBED Integrative Portfolio: In addition to submitting this assignment to the course instructor, you are also required to upload your assignment to your Integrative Portfolio. For important uploading instructions, visit your Integrative Portfolio Moodle course (GS002 or GS003). This requirement applies to all degree seeking students who initiate their degree program from fall of 2008 forward. Grading: Three exams (3x16%) Online forum posting In-class discussion leading Final integrative paper Evaluation (see below) 48% 16% (8% per assigned week, 2 assigned weeks) 10% (1 assigned week) 24% 2% EVALUATION: Owing to a change in Bethel Seminary policy, I am required to count your completion of the course evaluation at the end of the course as 2% of the final grade. I won’t be able to look at the evaluation text itself (have no fear!), but I will be able to tell whether you completed it or not, so I can add that 2% to your final grade. PARTICIPATION (involvement in our discussions; attendance is assumed, and mandatory!) will be used as a “straw in the wind.” That is, my observation of your involvement in class discussion will serve to push you, if your final grade is on or near a “line” between two letter-grades, toward either the higher or the lower grade. As stated in the Academic Course Policies, your completion of the course evaluation electronically at the end of the course “will be included as a factor in your final course grade.” See “Course Grading” above for how this will be calculated. All evaluations remain anonymous to the faculty. Academic Course Policies: Please familiarize yourself with the catalog requirements in the Academic Course Policies document on the Syllabus page in Moodle. You are responsible for this information, and any academic violations, such as plagiarism, will not be tolerated. HS501: Syllabus page 3 CLASS SCHEDULE: Date Jan 10-16 Week 1 Course questions/lectures WHAT IS HISTORY? HOW JEWISH WAS THE EARLIEST CHURCH LOOK? Introduction, history study, Jewishness of the earliest church Assignments ****See Moodle Forums: VI. Topics and Readings, below, for list of additional reading assignments for each week, beyond Gonzalez No postings due—a good time to get a jump on exam I by reading Gonzalez Jan 17-23 Week 2 Jan 24-30 Week 3 THE FIRST CULTURAL TRANSLATION OF THE GOSPEL. HOW DID THE CHURCH GROW TO DOMINANCE DESPITE PERSECUTION? HOW WAS THE CHURCH'S IDENTITY SHAPED IN ITS GROWTH?: Shift to a gentile church, The three authority structures, Christianizing the Empire Forum postings on discussions 2 (Early church-state relations) and 3 (atonement) due Wed (19th)/ Fri (21st)/ Mon (24th) HOW DID THE CHURCH DEFEND ITS DOCTRINE AND INTERACT WITH (GREEK) CULTURE?: Hellenization, The apologists and their defense of the faith In class: discussion 1 (Greek culture) led by Prof. Armstrong No in-class discussion this week Do assigned readings for next week's discussion 1 (Greek culture) In class: discussions 2 (Early churchstate relations) and 3 (atonement) led by students Forum postings on discussions 4 (creeds) and 5 (Christ’s divinity and humanity) due Wed/Fri/Mon Jan 31Feb 6 Week 4 WHY IS TRADITION IMPORTANT? HOW DID THE DOCTRINES OF CHRIST’S DIVINITY AND HUMANITY DEVELOP? Tradition and the Nicene Council (lecture and reading/discussion) Exam I due by midnight on Friday, Feb 4 on Gonzalez 7-17, (8-23), 31-108 (41-125) and lectures from weeks 1-3 Discussions 4 (creeds) and 5 (Christ’s divinity and humanity) No forum postings due this week—use the time to study for exam I! Feb 7-13 Week 5 Reading week 1 HOW DID EARLY CHRISTIANS "DO CHURCH"? WHERE DID MONASTICISM COME FROM? WHAT IS CHURCH?: Early church leadership, Anthony of Egypt and the origins of monasticism; “Models of Church” Forum postings on discussions 6 (early church leadership & worship) and 7 (Augustine and the Pelagians) due Wed/Fri/Mon No in-class discussion today Outline of integrative papers due in assignment area by midnight on Friday, Feb 11 HS501: Syllabus Date page 4 Course questions/lectures Assignments Feb 14-20 AUGUSTINE, FATHER OF WESTERN Discussions 6 (early church leadership Week 6 THEOLOGY: Augustine’s conversion and thought Reading week 2 No forum posts due this week; good time to study for exam II and work on your paper Feb 21-27 HOW DID THE WESTERN CHURCH Week 7 Feb 28Mar 6 Week 8 Mar 7-13 Week 9 BECOME THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH? How the West became Roman Catholic; Gregory the Great Exam II due by midnight on Friday, Feb 25 on Gonzalez 113-219 (131-260) and lectures from weeks 4-6 Forum postings on discussions 8 (Montanism & Donatism) and 9 (postChalcedon Christological controversies) due Wed/Fri/Mon HOW DID THE CHURCH’S FIRST MAJOR DIVISION HAPPEN, AND WHAT WERE THE DISTINCTIVES OF THE EASTERN CHURCH? How the East became Orthodox; Eastern distinctives compared to Western Discussions 8 (Montanism & Donatism) and 9 (post-Chalcedon Christological controversies) WHAT DID MEDIEVAL CHRISTIANS BELIEVE AND HOW DID THEY “DO” CHURCH? Ten key elements of the medieval worldview and four key theological ideas; Discussion 10 (dark ages church-state relations and heresy) note discussion 11 will happen next week Mar 14-20 HOW DID MONASTICISM DEVELOP Week 10 & worship) and 7 (Augustine and the Pelagians) Forum postings on discussions 10 (dark ages church-state relations and heresy) and 11 (Benedictine monasticism) due Wed/Fri/Mon No forum postings due—study for exam III and work on papers! Discussion 11 (Benedictine UNDER BENEDICT? WHAT DID THE monasticism) MEDIEVAL CHURCH LOOK LIKE Study for exam III / finish paper RIGHT BEFORE THE REFORMATION? Benedictine monasticism; issues in the medieval church, renewal; wrap-up HS501: Syllabus Date page 5 Course questions/lectures Mar 21 Assignments Exam III due by 11 p.m. on Monday, Mar 21, on Gonzalez 231-374 (269445) and lectures from weeks 7-10. Essay questions are: 1. What can the modern American church learn from Eastern Orthodoxy? 2. What can the modern American church learn from Medieval (Western) Christianity? Final integrative paper due by midnight on Monday, Mar 21, via the “Assignment” link on Moodle. Please do not submit via email or hard copy. Moodle forum postings I. Assignment We’re going to have topical discussions both on the Moodle forums and in the classroom. What we’re aiming for is to begin our topical discussions for each week in the Moodle forums and then continue and expand them in the classroom. During the course, each student will post on two primary topics and two secondary, for a total of six posts, in Moodle “topic forums” (the topic areas and readings for these are listed at the end of this document). In two weeks during the quarter you will post (1) one meaty presentation post on a primary topic, (2) one “probe” on the other student's post (secondary topic), and (3) one wrap-up post addressing the “probe” that the other student has made on your own primary post. If there is not a secondary topic during your week, post your probe on the student who shares your primary topic. Topics will be assigned to you during the first week. Here’s how it’s going to work: In the course documents area of the course’s Moodle site, you will find scanned copies of the contextualizing readings listed under “V: Topics and readings,” below. These contextualizing readings come from Everett Ferguson’s Church History: From Christ to Pre-Reformation and Mark Noll’s Turning Points. You will also find listed readings from Christian History magazine (marked “CH”), which are accessible via www.christianhistory.net (issues are sorted by number at the left of the main webpage, near the bottom). These readings, along with Gonzalez and some additional library research, will help you contextualize and understand the Bettenson material. Each week in which forum postings are due, you are responsible for reading the context material and assigned Bettenson readings associated with the topic assigned to you. Then you will need to post the following: (1) on your assigned topic, a two-page (500-word) initial post; HS501: Syllabus page 6 (2) on another student's topic (also assigned), a one-paragraph (roughly 75-word) probe; then finally (3) on your assigned topic, a two-paragraph (roughly 150-word) wrap-up post addressing the question(s) raised by the other student's probe. The terms “initial post,” “probe,” and “wrap-up post” are further explained under “III: Your three postings,” below. NOTE: In addition to the contextualizing reading for the two topics on which you are posting (either primary post or probe), you are responsible for the contextualizing readings for discussion #1 (week 3) and #12 (week 10). III. Your three postings (The deadlines for all three posts may be found in section IV below.) A. Your initial post Your two-page (500-word) initial post should use what you know from Gonzalez and the extra readings (e.g. Ferguson, Noll, the Christian History issues) along with at least two Bettenson excerpts: (1) from the contextualizing readings, explain briefly and contextualize the topical question listed in section V below, then (2) answer the question in brief, using at least two quoted passages from Bettenson to illustrate your answer B. Your probe Your one-paragraph (roughly 75-word) probe should pose at least two penetrating questions on the other student's post. You should read the contextualizing readings for that topic before posting your probe. Also, please probe on time, so your initial post-er can wrap up on time. C. Your concluding wrap-up post Your two-paragraph (roughly 150-word) wrap-up post should address the question posed by your respondent in a summing-up-and-clarifying statement, along with anything else you'd like to add in the way of clarification or further insight. III. Post grading These Blackboard forum postings are worth 16% of your course grade, calculated as follows: 5% for each initial post, 1% for each probe, and 2% for each wrap-up I may browse the posts, but they will be read and graded by my t.a., Laine Gebhardt, according to a clearly defined rubric. Here is that rubric: HS501: Syllabus page 7 5 points for initial post 1. Does it answer my topical question in at least abbreviated form (or does it answer some other question/s I didn't ask)? 2. Does the post meet the 500-word assigned length (or is it fewer than 450 words; don't worry about longer posts—penalize only those that are more than 1,000 words, reminding the student gently that they owe their reader the courtesy of keeping to the assigned length)? 3. Does it quote Bettenson at least twice (or not)? 4. Does it ground the answer in historical fact (or is it fuzzy and generalized)? 5. Does it set up the topical question (that I provide on pp. 7-12 or so of the syllabus) by putting it in historical context (or does it never ground the answer in historical context)? 6. Does it show evidence of reading the posted contextualizing materials (or, again, is it generalized and unhelpful)? 7. Would it be accessible to an "adult Sunday school" audience not familiar with the material (this is subjective of course, but depends a lot on the answer to "a," above, as well as to "f." Posts should not assume a lot of prior knowledge, nor should they use big, fancy words unexplained). 8. Is it cogently and clearly written (or difficult to parse/full of grammatical and spelling errors)? These areas are listed in order of their importance to the grade. Complete failure in any of these areas is grounds for taking off a full point. Out of courtesy to your respondent and to Laine, don’t exceed the 500 words by much. 1,000 words, for example, is way too long! 1 point for probe: a. Does it pose at least two penetrating questions? b. Is it on-topic—that is, does it really respond to the actual content of the other student's post? c. Is it readable/clear? d. Is it the assigned length of 75 words (or fewer than 60 or so)? Up to ½ point docked for complete failure in any of these areas. 2 points for wrap-up: a. Does it extend the thought of the primary post (or either repeat the info in the primary post or just flail about emptily)? b. Does it sum up and/or clarify something in the initial post (or is it completely unrelated to the initial post)? HS501: Syllabus page 8 c. Does it address the question/s posed (or go off on a tangent/avoid the question/s)? d. Is it the assigned 150 words (or fewer than 115 or so)? Again, could dock up to ½ point or even a full point for complete failure in any of these areas. IV. Discussion leading The week after you do one of your two primary posts, you will be leading discussion on the topic on which you posted (see "Discussion leading on Bettenson readings," below). This is an opportunity for us to help each other explore further the themes and questions we uncovered during our research for the post, in a way that goes beyond the limits of discussion-board posting. V. Deadlines Each week when you have a posting assignment: Post your primary post by midnight on Wednesday night. Post your probe by noon on Friday. Post your wrap-up post to the other student's probe by midnight on Sunday. All posts receive an automatic time-stamp when you post them. Late work will be docked, and will also, in the case of initial posts and probes, prevent your fellow students from completing their assigned probes or wrap-ups—PLEASE be sure to complete these on time! If, however, your assigned probe-r does not post on time, then a statement extending the thought of your initial post with new ideas & material is acceptable. VI. Topics and readings NOTE: All contextualizing readings not in Bettenson or CH are posted in Course Documents. All students are to read the material for topic 1, as preparation for our in-class discussion on that topic in week 3. 1. How did Christians interact with Greco-Roman culture—especially Greek thought? What were the results for Christian thought & practice (especially theology)? Bettenson, pp. 1-7: References to Christianity in classical authors, Christianity and ancient learning CH 80: The First Bible Teachers, esp. Christopher Hall, “Classical Ear-Training”; Joseph Lienhard, “The First Battle For the Bible” Pelikan, Jesus Through the Centuries, chap. 3: "The Light of the Gentiles"; chap. 5, "The Cosmic Christ" HS501: Syllabus page 9 2. What did church-state relations look like in the Roman world before and after legalization? How did the church handle its political position as persecuted (large) minority, as tolerated minority, and eventually as official majority? Bettenson, pp. 7-25: Church and state in the Roman Empire, including persecution and martyrdoms; Church and state in the Roman empire after legalization CH 27: Persecution in the Early Church Pelikan, Jesus Through the Centuries, chap. 4: "The King of Kings" 3. How did the earliest Christians think about the atonement? What historical factors might have led to those ways of thinking about the atonement? And what do we think of those atonement views, as faithful exegesis and theology? Bettenson, pp. 32-38: The person and work of Christ Library: check out discussions of early atonement thought in encyclopedias of the early church and other reference works (don't forget your friendly seminary librarian is available to help with this); also see the pages of primary source excerpts from early church documents on the atonement (I will provide) 4. What is a creed? How did creeds develop—both in general, and the particular creeds recorded in Bettenson? What are the differences between these creeds, and how and why did those particular differences come about? Bettenson, pp. 25-29: Creeds CH 85: The Council of Nicaea, Why a Creed? : A Conversation with Robert Louis Wilken; Christopher A. Hall, How Arianism Almost Won: After Nicaea, the Real Fight Began; D. H. Williams, Do You Know Whom You Worship?: Did the Nicene Creed distort the pure gospel, or did it embody and protect it?; Lewis Ayres, The Final Act: It took almost 60 years for the church to make Nicaea its standard of faith. And other articles: browse the whole issue! 5. Describe the struggle of the early church both on the divinity of Christ and on the relationship between his divinity and his humanity, up to the Council of Chalcedon. Bettenson, 38-57: Heresies concerning the person of Christ, The problem of the relation of the divinity and the humanity in Christ Ferguson (Moodle): chap. 13, 255-267 (about 26 pp) Backup reading: Noll (Moodle): chapter 3, 65-82 (about 18 pp) CH 96: The Gnostic Hunger for Secret Knowledge browse issue; CH 51: Heresy in the Early Church browse issue; CH Issue 85 (as above) HS501: Syllabus page 10 6. The Bible doesn’t give us a clear, organized rulebook for “how to do church.” So first- and second-century Christians worked their ways through various ideas and practices related to leadership and worship. Describe and assess several interesting developments in these areas. Bettenson, 68-86: The church, the ministry, and the sacraments in the first centuries CH 37: Worship in the Early Church; CH 17: Women in the Early Church Library: check out discussions of early church worship in encyclopedias of the early church and other reference works (don't forget your friendly seminary librarian is available to help with this) 7. One of Augustine’s biggest fights was against the Pelagians. How and why did this issue of the human role in our salvation arise, how did Augustine respond, and how did the fight play out in the church, post-Augustine? Bettenson, 57-68: Pelagianism, human nature, sin, and grace, including Augustine’s response and the semi-Pelagians CH 67: Augustine, esp. Robert Payne, “The Dark Heart Filled with Light”; David Allen, “SemiAugustinians”; Roger Olson, “Fighting Words” Pelikan, Jesus Through the Centuries, chap 6: "The Son of Man" 8. Both Montanism and Donatism raised important theological and practical questions about ecclesiology—that is, the nature of the church. How did the church respond to these challenging questions, and what did they affirm about the nature of the church in response to the Montanists and Donatists? Bettenson, 84-86: Two heresies on the nature of the church/ ministry: Montanism & Donatism CH 51: Heresy in the Early Church, esp. “Testing the Prophets” Library: check out discussions of Montanism and Donatism in encyclopedias of the early church and other reference works (don't forget your friendly seminary librarian is available to help with this) 9. Describe how the struggle of the early church on the relationship between his divinity and his humanity continued after the Council of Chalcedon Bettenson, 97-106: From Chalcedon to the East-West Breach (1. Nestorians, Monophysites, Zeno’s Henoticon; Second Council of Constantinople, “three chapters,” 553; Monothelites, Third Council of Constantinople, 681) Ferguson (Moodle): chap. 16, 306-313; chap. 17, 327-331 HS501: Syllabus page 11 10. How did church-state interaction and the control of heresy continue to work themselves out in the so-called "Dark Ages" (500-1000 AD) and beyond into the Middle Ages? Bettenson, 102-105 (Nicholas I vs. Louis II—Independence of Apostolic See); 123-127 (Pope and Imperial Elections); 146-149 (Church and Heresy) (about 13 pp altogether) Ferguson (Moodle): chap. 18, 375-378; chap. 24, 469-474; chap. 24, 501-509; chap. 24, 520-523 (about 23 pp altogether) CH 22: Waldensians 11. How did Benedictine monasticism describe a life given over to God? What were the key disciplines and benefits of that life? Bettenson, 127-141 Noll (Moodle), chap 24, 83-105 CH 93: Benedict: A Devoted Life Discussion leading on Bettenson readings: Each student will lead the in-class discussion for one of the two topics on which you are posting to the Moodle forum. There will be 10 student-led discussions during the course (plus one, discussion # 1, that I will lead, for which you are also responsible to do contextualizing readings). Each will be led by somewhere between 1 and 4 students, depending on class size. The discussions should take roughly 30-40 minutes each. When you lead discussion, you and your fellow discussion-leaders are expected to lead off with about 15-20 minutes of "set-up." During this set-up, leaders will do the following (you should meet together before you lead the discussion, to decide who will do what; you can divide things up any way you like, but as a rule of thumb, allow at least 5 minutes per leader): 1. Contextualize the topic using what you know from the readings posted on Moodle, the recommended CH issues/articles, and the appropriate sections of Gonzalez. Essentially, you are putting both the overarching topical question (see list above) and any subquestions you pose (see #2 directly below this paragraph), along with the relevant Bettenson documents and particular quotations from those documents, into the larger historical context of early church history—that is, in the framework of what you discovered in your readings. 2. Pose, as "sub-questions" to the overarching topical question listed above, several fruitfully discussable questions (one to two per presenter is good). See below for definition of a "fruitfully discussable question." 3. In the course of presenting 1 & 2 above, refer to specific quotations from at least 3 Bettenson documents (that's a total of 3, not three per leader!) HS501: Syllabus page 12 4. As you set up the discussion, you must use at least one of: (1) Powerpoint or (2) handouts. Use of small, carefully selected bits from the Moodle documents and/or CH issues is encouraged, but don't clog your set-up with this material. 5. After your set-up, you will be primarily responsible for fielding and answering your fellow students' questions. I may interject some answers as well, but I will be attending to your ability to field questions; this is definitely part of your discussion-leading grade. 6. By the end of the class in which you lead discussion, give Prof. Armstrong a hard copy of both your discussion notes and any handouts used, and/or (shortly after the class), email to him a copy of any Powerpoint used. Note well: Having your discussion-leaders' notes allows me to double-check your discussion-leader grade against what I perceived in class. These notes need not be formatted as full paragraphs, etc. Handwritten notes are OK, but please try to make them legible! A tip: when dealing with the Bettenson quotations themselves, you’ll want to help your audience understand what, precisely, the author of the document was saying. What is/are the central contention(s) or theme(s) of the document/excerpt/quotation? What arguments does the author marshal in support of the contention(s) or what evidence does the author give to support the themes? And of course, how did those arguments and that use of evidence relate to the historical context of the author? HS501: Syllabus page 13 Fruitfully discussable questions: a definition Your interpretive questions must be fruitfully discussable—or in other words, non-trivial. First, to be discussable and non-trivial, your interpretive question must not lead to a dead end because it is unanswerable from the primary texts. So the question, “Did Gregory the Great secretly desire to overthrow the papacy?” or the question, “Would Gregory the Great have espoused Confucian thought?” are both trivial questions because there’s no way to answer either of them from the texts. Any answer we might give would be conjecture or would require some other source text or piece of evidence we don’t have. Note that a “trivial” question in this sense is not necessarily an un-important one—just not useful for discussion. Second, to be discussable and non-trivial, your interpretive question must not lead to an immediate, obvious answer. So, “Did Cyprian really believe there was no salvation outside the church?” would be trivial because we can immediately answer the question from the primary texts. Again, “trivial” in this sense does not mean un-important, just not fruitful for discussion. One possible non-trivial interpretive question on Cyprian would be this one: “Why did Cyprian place so much emphasis on the church as ‘mother’?” Though the presenter may not have an immediate answer to this question, it could spark a good discussion that would draw not only on the text itself, but on what Cyprian’s contemporaries and antecedents thought about the church—and the social, cultural, and theological contexts in which they thought these things. Such a discussion could help us work toward important truths about early church ecclesiology. Note that I say we work toward these truths. I don’t believe we can ever come to the definitive, complete, comprehensive, water-tight truth about this or any other important question related to history. It’s the Law of Diminishing Certainty: the more important and “deep” the question, the harder it is to get a single, simple, conclusive answer. This may discourage those of you who come to the study of history on a quest for objective truth—defining truth in strong modernist terms as absolute certainty. Or it may confirm those of you with tendencies toward strong postmodernism in the opinion that history-writing is just “a joke we play on the dead”—imposing whatever fanciful interpretations we want to on the past, and let the most convincing orator (or the person with the bucks and the social power to publish the most books) win. I now fall in neither of these extreme camps—though during my graduate studies I went through both of them. I’ve finally cast my lot with the Pietists. This is my position: If we ask good, meaty, non-trivial questions in our study of what human beings have said and done in history, we will learn useful, transformative things. In other words, history repays those who join its interpretive conversation: they come away better people for it. In the end, for our purposes, the journey is, in a significant sense, the destination. That’s why we’re investing time in primary source reading, presentation, and discussion in this course: we’re learning how to become our own interpreters of history. HS501: Syllabus page 14 Integrative paper I. Find a single issue in the church today that concerns you personally. This should not be too broad. It should be a problem or opportunity that shows up in some single branch or area of church life today. There are two ways to go on this. (1) You can choose an issue facing (with particular acuteness) a single denomination or even a single congregation— perhaps your home church. Or (2) you can choose a single, tightly defined practice or idea that may show up across a variety of churches, say within the orbit of “modern American evangelicalism.” In either case, you will think about what is at stake for this particular church or what is at stake in the area of this particular idea or practice as it affects a broader group of churches. How would resolving the issue you have identified benefit the church? II. Find a single historical crux—that is, a single document, single event, single person’s idea, etc.—from pre-Reformation history in which some version of that same issue emerges, which you feel could help today’s church wrestle with that issue upon which you briefly “editorialized.” (You will probably need to find your “modern issue” and your “historical crux” at the same time—before you start writing either the editorial or the historical portions of this assignment.) III. Study that historical “crux” (document, event, person’s idea, etc.) by reading a balanced bibliography of primary and secondary sources—at least two and preferably three or more of each. In other words, you want to know both what people of that time thought was going on in that crux, and what historians since that time have said about it. IV. Now you will write a three-pronged, 8-10 pp paper, following this format: A. Describe your issue in the church today in detail, as if you were writing a brief editorial article for Christianity Today. That is, write in the first person—ideally basing your remarks on your own observations and experience. Again, you want to show your readers exactly what the issue is, who it affects, and how the church would benefit from resolving this issue. B. Using the best canons of historical writing (see provided documents on how to write historical essays), write a summary/analysis/interpretation of how that issue played out at your chosen historical crux. Very important: you must acknowledge ways in which the contemporary issue differs in how it is playing out today from how it played out at your historical crux. Different times and contexts entail different presuppositions that people find convincing in making an argument. Your summary/analysis/interpretation should follow this format: HS501: Syllabus page 15 1. Start with the who-what-where-why-when. We need names, years, places. Historical writing falls apart without these. 2. Set up the context of your crux, the stakes and stakeholders, the reasons why people did what they did as the crux unfolded. 3. Now analyze your single document, event, idea, etc.: Outline the logic of how the issue played out: what argument or solution prevailed, and why? What grounds did the players use for deciding in favor of that argument or solution? From what agreed-upon warrants and shared presuppositions did they reach their conclusion? 4. Now show how that conclusion played out concretely in the flesh-and-blood church of that historical moment: in belief, practice, organization, worship, or other appropriate aspect(s) of church life 5. Give your interpretation (assessment) of the way your crux played out: was it beneficial or harmful for the church? Did it make sense in terms of Scriptural teaching, human psychology/sociology, theological integrity, etc.? (Choose your own criteria) C. Finally, return to your “Christianity Today editorial” style and write a conclusion on the issue in the church today based on your research into the historical crux: How can knowing the ins and outs of the historical crux you have just presented and analyzed help us resolve this issue that faces us today? I want to make something crystal clear about the format of the final paper: THE BULK OF THE PAPER MUST BE DEDICATED TO THE ANALYSIS OF YOUR HISTORICAL "CRUX." Don't be tempted, in other words, to spend too much space on the editorial "set-up" or "wrap-up." In order for this to be properly a history paper (though of course an integrative one), you need to limit the two "editorial" sections, front and back, to NO MORE THAN A PAGE OR AT MOST TWO EACH. Again, THE GUTS OF THIS PAPER IS THE HISTORICAL ANALYSIS. I tried to indicate this by giving that part of the paper a much more detailed treatment than the other parts when I describe the assignment in the syllabus. So gauge the relative weight you should be giving the historical/analytical and modern/journalistic material in the paper accordingly. One more note of guidance: for examples of writing about contemporary issues that draws from historical analysis, see CH Issue 94: Building the City of God in a Crumbling World, via www.christianhistory.net . HS501: Syllabus page 16 Note the care taken by the historian-authors in this issue: they do not impose today’s perspectives on the past (that is called “presentism,” and is anathema to historians). Rather, they seek an accurate picture of the past, from which they can extrapolate lessons for the present. That is the kind of care and historical integrity with which you are to write this integrative assignment. However, note that these articles are by and larger broader and more general than this assignment. So that you do not either flounder in a sea of research possibilities or spout unsupported generalizations, you will need to narrow your focus—both in the modern issue you address (that’s why I caution you to choose a single church or a single idea or practice) and in the historical crux (ditto here: you really do need to pick a single document, person’s idea, or event, to keep this assignment from getting out of hand!) HS501: Syllabus page 17 Exam study guide Gonzalez Study Items, Test I Diaspora Judaism Stoicism Persecution: Domitian Ignatius of Antioch Persecution: Marcus Aurelius Lofty Criticism against Christianity Apologists: Tatian and Justin Arguments of the Apologists Gnosticism Marcion Apostolic Succession Irenaeus Clement of Alexandria Tertullian: Prescription against Heretics Tertullian: Montanism Origen Decius The Lapsed: Cyprian and Novatian Christian Worship Organization of the Church Persecution: Galerius Christian art Gonzalez Study Items, Test II Licinius Constantine: conversion Impact of Constantine Constantine: churches Eusebius of Caesarea Origins of monasticism Anthony Pachomius Martin of Tours Donatist schism Outbreak of Arian controversy Council of Nicea Julian’s religious policy Athanasius: the early years Athanasius: exile Macrina Basil the Great Gregory Nazianzus Ambrose: the bishop and the throne John Chrysostom Jerome Augustine: path to faith Augustine: theologian End of an era Gonzalez Study Items, Test III The barbarian kingdoms: Britain Benedictine monasticism Pope Gregory I Christology: Apollinaris, Nestorius, Eutyches Eastern Church: further debates Charlemagne: theological activity Charlemagne: decay in the papacy Cluniac reform Papal reform Papcy vs. Empire: Henry IV The First Crusade Franciscans Pope Innocent III Anselm, Abelard Aquinas Middle Ages: new conditions Boniface VIII Great western schism Conciliar movements John Wycliff John Huss Savonarola The mystical alternative The later course of Scholasticism HS501: Syllabus page 18 Helps on reading primary documents and writing essays IMPORTANT for your reading and interpreting of the primary documents excerpted in the Bettenson book: Additional reading at beginning of class (by first class session, if possible; or at least by second class session): How to Read a Primary Source (Bowdoin: http://academic.bowdoin.edu/WritingGuides/primaries.htm) A primary document is any document written by the historical figures themselves. It is distinct from a secondary document (though sometimes the line blurs), which is written, almost always in the third person, by another person about a historical figure. So, if we’re just reading the words of the historical figures themselves, then that’s pretty straightforward, right? The writers are just giving eyewitness, first-hand accounts of what they have experienced. And we just read them, and then we know what “really happened” in history, right? Of course, it’s not that simple. If we are really going to learn from primary documents, we must bring to them a prepared mind. Inattentive, unprepared reading will result in skewed, caricatured— or, frankly, dead wrong—ideas about what “really happened,” or even about what the writer was trying to tell us (the two are not always the same thing!) But don’t despair: with some basic direction to show you which tools you’ll need to bring to the job, any non-historian can begin mining primary sources for the gold and gems they contain. And that’s when the real fun of learning history begins. First, you will feel much closer to the life of the past when you read such sources. There is no substitute for hearing those voices from the past resurrected in vivid power as you read. Second, many students find the historical detective work you need to do when reading a primary source stimulating--even addictive (really!) To get you started, the link above is a “tip sheet” on how to work with primary documents. It is short and succinct, but powerfully helpful, especially to students who have not been in a history classroom in a while. Read it carefully, early in the course: IMPORTANT for your online forum postings, exam essays, and final integrative paper: Two final notes on essay-writing: First, I have a friend who teaches at Westmont and has done students everywhere a service with a very strict (and appropriate) list of suggestions about how to put essays together for his classes. You can find my friend’s “A Few (Strong) Suggestions on Essay Writing” at the following web address: http://www.westmont.edu/~work/material/writing.html . Though I am not as strict as he is, following his suggestions carefully will result in a near-guaranteed improvement in your papers for this course—and future courses. NOTE CAREFULLY his words on plagiarism. Bethel has a policy similar to Westmont's. You are responsible for knowing and following Bethel's policy on plagiarism. DO NOT use other people's wordings and ideas without properly citing them. Doing so results in an automatic "F" on the course! HS501: Syllabus page 19 Second, I want to share with you my favorite web sources for writing help. Some students will benefit from these more than others, but all should find something useful here. The first is a couple of lists of helps for writers that I put together while working as a writing tutor at Duke. You can find these helpful lists at the following web addresses: http://uwp.aas.duke.edu/wstudio/resources/writing.html, and http://uwp.aas.duke.edu/wstudio/resources/editing.html. Also, almost everyone can also benefit from this site: http://bcs.bedfordstmartins.com/smhandbook/default.asp. It contains not only a list of the twenty errors most commonly found in student papers, but a concise explanation of each error and (when you click on the link to "Exercise Central") exercises to help you identify and correct these errors. To do the exercises, just do the free "student registration" at the Exercise Central page, entering your name and your own email for “instructor email.” You’ll find that you can browse the errors and do the exercises quite quickly. Bookmark this site and the sites in the previous paragraph, and refer to them throughout your seminary career and beyond!