Religious Establishment - Northern Illinois University

advertisement

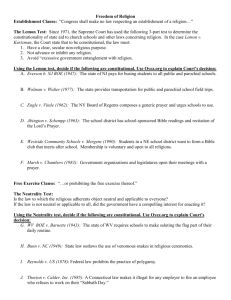

Prayer and Religious Teaching in Public Schools The Bill of Rights Institute Indianapolis, IN, September 29, 2012 Artemus Ward Department of Political Science Northern Illinois University aeward@niu.edu Engel v. Vitale (1962) • New York composed and required a prayer to begin the school day: “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers, and our Country.” • Justice Hugo Black held: “Petitioners argue [that] the State's use of the Regents' prayer in its public school system breaches the constitutional wall of separation between Church and State. We agree since we think that the constitutional prohibition against laws respecting an establishment of religion must at least mean that in this country it is no part of the business of government to compose official prayers for any group of the American people to recite as a part of a religious program carried on by government.” Abington School District v. Schempp (1963) • Pennsylvania law declared that at least 10 verses from the Bible shall be read without comment at the beginning of each public school on each school day. At Abington High, the verses were read over the loud speaker and were then followed by a recitation of the Lord's prayer, during which students stood and repeated the prayer in unison. Students who did not want to participate could leave the room. The Schempps (above) objected to the law and filed suit. • The Supreme Court asked what the purpose and primary effect of the policy were and found it unconstitutional. The justices reasoned that the state passed the law to promote religion and the effect was to coerce students to participate in religion. • A majority of Americans have never approved of the Court’s holdings in Engel and Schempp. Today only about 1/3 agree. Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) • • • In 1928, Arkansas enacted a law making it a crime for any state university or public school instructor “to teach the theory or doctrine that mankind ascended or descended from a lower order or animals” or to “adopt or use…a textbook that teaches” evolutionary theory. The law was modeled on Tennessee’s 1925 law that was the subject of the celebrated Scopes monkey trial where America’s most famous criminal defense lawyer—Clarence Darrow—defended a 24-year-old High School teacher—John Scopes—who taught evolution against the state, voluntarily led by former Presidential candidate and Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan—perhaps the leading fundamentalist of the day. The history of the law’s adoption makes it clear that its purpose was to further religious beliefs about the beginning of life. For example, an advertisement placed in an Arkansas newspaper to drum up support for the act said: “The Bible or atheism, which? All atheists favor evolution…. Shall conscientious church members be forced to pay taxes to support teachers to teach evolution which will undermine the faith of their children?” Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) • The case began in the mid-1960s when the school system in Little Rock, Arkansas, decided to adopt a biology book that contained a chapter on evolutionary theory. • Susan Epperson, a High-School biology teacher, wanted to use the new book but was afraid—in light of the 1928 law—that she could face criminal prosecution if she did so. • She asked the state courts to nullify the law and when they refused she appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) • Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice Abe Fortas relied heavily on the reasoning in Everson: “The First Amendment mandates governmental neutrality between religion and religion, between religion and nonreligion.” • “Arkansas’ law cannot be defended as an act of religious neutrality. Arkansas did not seek to excise from the curricula of its schools…all discussion of the origin of man. The law’s effort was confined to an attempt to blot out a particular theory because of its supposed conflict with the Biblical account, literally read. Plainly, the law is contrary to the mandate of the First…Amendment.” Wallace v. Jaffree (1985) • The Court became more conservative in the 1970s and 80s as Republican presidents were able to replace many of the liberal separationists. • In Marsh v. Chambers (1983), the Court upheld prayers before legislative sessions. Ignoring the Lemon test, the justices said that tradition and history were determinative. • Wallace involved an Alabama law authorizing a daily period of silence in all public schools “for meditation or voluntary prayer.” The law’s sponsor said that the purpose was “to return voluntary prayer to our public schools.” • Ishmael Jaffree, a lawyer for the Legal Services Administration, objected when the law was implemented in his son’s kindergarten class. The teacher led the students in saying: “God is great, God is good, let us thank Him for our food; Bow our head, we all are fed, give us Lord our daily bread.” • The Reagan administration supported the state and urged the Court to uphold the law. Many hoped the Court would overturn Engel and Abington. Wallace v. Jaffree (1985) • The Court applied the Lemon test, found that the law’s primary purpose was not secular, and struck down the law. • Writing for a 6-3 majority, Justice John Paul Stevens explained that the only purpose of the law was to return prayer to the schools and made a distinction between prayer and a moment of silence: • “The legislative intent to return prayer to the public schools is, of course, quite different from merely protecting every student’s right to engage in voluntary prayer during an appropriate moment of silence during the school day.” • “The [original] statute already protected that right, containing nothing that prevented any student from engaging in voluntary prayer during a silent minute of meditation.” • “The addition of ‘or voluntary prayer’ indicates that the state intended to characterize prayer as a favored practice. Such an endorsement is not consistent with the established principle that the government must pursue a course of complete neutrality toward religion.” Wallace v. Jaffree (1985) • But many justices expressed their displeasure with the Lemon test. In dissent, Chief Justice Burger lamented that the majority’s “extended treatment” of the Lemon test “suggests a naïve preocupation with an easy, bright –line approach for addressing constitutional issues.” • Justice Rehnquist’s dissent questioned the Court’s entire approach to establishment clause cases beginning with Everson. • He said the Court was wrong to “concede” Jefferson’s metaphor of a “wall of separation” or to etch into law such strict separation. He asserted that for the four decades since Everson, the Court had operated under a misguided understanding of what the framers meant by religious establishment. • The truth, according to Rehnquist, was that the founders, particularly Madison, intended something more in line with the nonpreferential position that the establishment clause simply “forbade the establishment of a national religion and forbade preference among religious sects or denominations…. It did not prohibit the federal government from providing nondiscriminatory aid to religion.” Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) • After Epperson, organized interests—particularly religious groups— lobbied state legislatures to pass new laws. • Louisiana enacted the Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and Evolution-Science in Public School Instruction Act in 1981. • This law was different from the one struck down in Epperson because it did not outlaw the teaching of evolution. Rather, it prohibited schools from teaching evolutionary principles unless theories of creationism also were taught. Hence, teachers had to teach both or none. • There were two arguments to justify the law 1. Evolutionary theory is a religious tenet, and the religion is secular humanism. If evolution is taught so should creationism, which has its origin in a literal reading of Genesis. In other words, public school teachers must give equal time to the two primary “religious” views of the origin of humankind. 2. Creationism is a science just like evolutionary theory and, therefore, deserves equal treatment in public school curricula. Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) Don Aguillard and Sharon Epperson • • • • • Represented by the ACLU, Assistant Principal Don Aguillard and several teachers, parents, and religious groups filed suit. Supporting their argument were 72 Nobel prize-winning scientists, 17 state academies of science, and 7 other scientific organizations. The National Academy of Sciences said in their legal brief: “The explanatory power of a scientific hypothesis or theory is, in effect, the medium of exchange by which the value of a scientific theory is determined in the marketplace of ideas that constitutes the scientific community. Creationists do not compete in the marketplace, and creation-science does not offer scientific value.” The ACLU argued that the legislature intended to give equal time to a particular religious view, in violation of the Establishment clause. The state argued that creation science consists of scientific evidence not religious concepts. It is no less scientific than is the theory of evolution. They also argued that the act’s primary purpose was to advance academic freedom. Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) • • • • • Writing for a 7-2 majority, Justice William Brennan applied the Lemon test and held that the law failed the first prong: it was not passed for a secular purpose. The Court reasoned that the legislature’s stated purpose—to "protect academic freedom“—was a sham because teachers already had academic freedom to teach what they believed was appropriate. Instead, the law limited their ability to make that decision. Indeed, the state claimed that “academic freedom” meant teaching “all the evidence” yet one alternative was to teach neither creationism nor evolution. Hence, under that definition, teaching neither would be the opposite of “all the evidence.” Instead, the legislature had a "preeminent religious purpose in enacting this statute." However, the justices did note that alternative scientific theories could be taught: “We do not imply that a legislature could never require that scientific critiques of prevailing scientific theories be taught. . . . Teaching a variety of scientific theories about the origins of humankind to schoolchildren might be validly done with the clear secular intent of enhancing the effectiveness of science instruction.” Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) • Justice Antonin Scalia, and Chief Justice Rehnquist dissented. • They construed the term "academic freedom" to refer to "students' freedom from indoctrination", in this case their freedom "to decide for themselves how life began, based upon a fair and balanced presentation of the scientific evidence". • They also criticized the first prong of the Lemon test, noting that "to look for the sole purpose of even a single legislator is probably to look for something that does not exist". • Campaigns to include “intelligent design” have only increased since this decision. Public opinion polls have found that 2/3 of American believe that God definitely or probably created human beings and well over half favor teaching creationism along with evolution in public schools. Lee v. Weisman (1992) • Is a state-approved, clergy-led prayer at a public school graduation constitutional? • Justice Kennedy initially voted that it was, switched his vote, and finally struck down the policy for a 5-4 majority. • Instead of applying the Lemon Test, Kennedy applied what Justice Scalia mockingly called the “psycho-coercion test” • Kennedy said that “subtle coercive pressures exist and the student had no real alternative which would have allowed her to avoid the fact or appearance of participation.” Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000) • The justices faced a tradition of long standing in many communities: public prayer at high school football games. • At issue was the policy of a Texas public school district that allowed student-led invocations to be delivered on the public address system during pre-game ceremonies. • To ensure continuing support for the practice, the school district required an annual vote of students, by secret ballot, on whether they wanted public prayers at the games. If the vote favored the invocations, a second election took place to select a single student who would deliver the prayers at all home games for that season. • The school required that the prayers be consistent with the district’s policy goals: to solemnize the event, to promote sportsmanship and safety, and to establish the appropriate environment for competition. Otherwise, the content of the message was left to the discretion of the student delivering it. Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000) The Court struck down the policy 6-3. • • Writing for the majority, Justice Stevens employed three different standards in order to satisfy each of the justices in the coalition. • To satisfy Justice Sandra Day O’Connor he said that the practice constituted an endorsement of religion with the government sending a religious message about who was an insider or outsider. • To gain Justice Kennedy’s vote, he used the coercion argument that, although generally voluntary, some students (players, band members, cheerleaders, etc.) were required to attend. Furthermore, there is often times strong peer pressure for members of the community to attend . • Finally, he explained the first prong of the Lemon test was violated because the government policy had a religious purpose. • In dissent, Chief Justice Rehnquist—joined by Justices Scalia and Thomas—said the majority opinion “bristles with hostility to all things religious in public life” and that religious expression by private individuals at public events is permissible. Elk Grove v. Newdow (2004) • The Pledge of Allegiance has included the phrase “under God” since 1954. • California requires public elementary school teachers to lead students in the Pledge. • Newdow, an atheist, challenged the Pledge that his daughter was required to recite. • The Court ducked the issue by holding that Newdow, as a divorced father who did not have legal custody of his daughter, did not have standing to bring the suit. In his opinion for the Court, liberal Justice John Paul Stevens added: “[The Pledge’s] recitation is a patriotic exercise designed to foster national unity and pride in those principles.” • Still, Rehnquist, O’Connor, and Thomas went to great lengths in separate opinions to explain why the Pledge was constitutional. Conclusion • In the area of school prayer and teaching religion in public schools, the Court has been fairly consistent. • Unlike in other sub-categories of Establishment Clause jurisprudence, the justices have been generally separationist. • Although the justices have squabbled over the most appropriate test to apply, the outcomes have never been in serious doubt: prayer and religious instruction in public schools is unconstitutional.