Cadastral Water Boundaries - Neville Brayley

advertisement

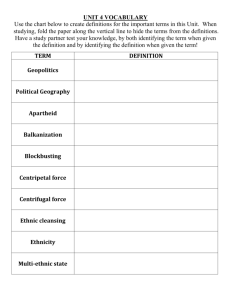

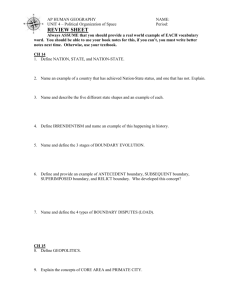

Cadastral River & Creek Boundary LAW & LORE Neville L. Brayley LS April 2015 What we will look at • The effects of some LAW and LORE relating to natural non-tidal water boundaries, and how they relate to each other. • What impact Section 5 of the Water Act 1905 had on freehold land already alienated to the centreline of rivers and creeks. • What did the early surveyors from the 1850’s to about 1900 measure to when using a water course as a crown boundary? • Does the 1881 Order in Council have any effect on land granted “ad medium filum aquae”, and how does that impact us today? • A case study of LAW and LORE and their effects on boundaries Setting out involves preparation This included re-reading over old notes and looking up new resources. Some information is quite specific in relation to the case study. Some information is a means to the end. Other information was just so interesting that I simply had to include it. I trust that the LAW and LORE presented can be used as a practical guide when determining water boundary issues. What’s Included & Excluded? INCLUDED: • Freehold land directly abutting a non-tidal river or creek • Crown Boundaries along non-tidal water courses EXCLUDED: • Tidal Ocean Boundaries • Tidal Rivers • Tidal Lakes, Lagoons & Channels • Islands (disappearing and appearing in rivers & creeks). • Islands (disappearing and appearing along the sea shore). • The Murray River State boundary. • Water boundaries created in a Plan of Subdivision that are NOT Crown Boundaries. • The Closer Settlement Act Background In recent years it has become apparent to me that I have been in a privileged position since embarking on my career as a Land Surveyor. In particular with regard to water boundaries, the reasons for this include: • The numerous water boundary surveys I have undertaken. • The many water boundaries on titles (and Old Law deeds) that I have considered in the preparation of a plan, even though a field survey of these may not have been undertaken. This may be because my project was a partial survey, or non-survey type of plan. • The access I have had to highly experienced people such as Peter Knights, Kevin Bourne, Geoff Westcott, and several “more recent” surveyors such as Barrie Bremnar, Peter Williams and Rob Lungren, to be able to discuss natural boundaries with. To all of these people I am indebted to their contribution to my knowledge base. • To have spent 30 working years in South West Victoria where most of the land that was alienated “near” water (creeks, rivers, lakes and the ocean) was actually to the centreline, bank, mean high water mark or whatever is applicable. Often the land was still held in the General Law system. • To have been able to study the impacts of and apply the laws such as the 1881 Order in Council, the 1905 Water Act and the (incredibly interesting) Closer Settlement Act. This CS Act is a topic all of it’s own • To have experienced surveys and situations where creeks went from simply passing through the land and not being a boundary, becoming a Crown Boundary in the next Crown Allotment, from a single line creek to a two line creek, to then becoming a Parish Boundary. These range from full survey to partial survey, and occasionally all occurred within the same project. This has allowed me to observe and physically survey various banks, both lower and upper. And then understand and apply the knowledge and experience I have gained. • To have carried out surveys with Southern Ocean frontage and needing to determine the Mean High Water Mark, and what that entails. • To have worked alongside, and been able to rigorously discuss water boundaries, with my colleagues of over 20 years, Mark Dore & Dale Minney, both of Hamilton. • To have had, and still maintain, a passion for rural cadastral surveying. This extends to the love of actually surveying the water boundary, rather than avoiding it. • To now also work in another jurisdiction (Northern Territory) and learning mountains of new stuff about water boundaries, tidal issues where a vast range of tidal movement exists (up to 7 metres), different types of land tenure and Aboriginal Land Rights issues. Interesting banks to survey • Becoming an Examiner for the Surveyors Registration Board of Victoria provided me with an insight into this privilege. Every rural project I examined that contained a water boundary has had deficiencies. This is in part due to the candidates and the Supervising Surveyors have very limited resources to turn to. What is known by some of us old rural surveyors, is simply not written anywhere. That experience is what I call LORE. • The following is how this LORE is intertwined with the LAW, enabling us to correctly determine cadastral boundaries along natural water courses. • The origin of preparing this paper came from one particular Examination. The candidate had chosen a parcel of General Law land with a water course along the western boundary. Nothing too unusual about that. Naturally I thought “he had better be thorough in detailing his knowledge of the water boundary”. However my interest was additionally piqued immediately upon inspection of the litho, or Current Record Plan. This showed that water course as a two lined creek. • The circumstances of this particular Rural Cadastral Project are used here as the Case Study. Crown Allotment 22 has a “two line Creek” as an abuttal I suspect many of you will be thinking “so what?” It’s just a water boundary, just pick up the bank, compute the area, draw the plan and move on. However, what are you going to put in your Surveyors Report? How detailed are you going to be about investigating the history of the parcel? What if you are doing a partial or non survey? What do the dimensions on the Crown Grant mean? What does the Crown Grant area represent? Does any of this really matter? Proper determination of water boundaries is never simple. Every case should be thoroughly investigated and you should know the full history of the land contained in the Crown Grant. Unfortunately there is limited written information for surveyors to research this sort of knowledge. So how would you even know that certain traps await? And what lore applies? Or who to even discuss any of this with? There is no shame in not knowing in detail an area of cadastral surveying. There is a serious problem however if you pretend to! • In the examination I was about to embark on I wondered would the candidate show an understanding and appreciate the two line creek, and explain the ramifications? And demonstrate all the knowledge he knew about issues relating to watercourse boundaries. If he doesn’t, surely I can guide him through the process with a carefully worded requisition to find out the correct answer. • In preparing the requisitions for the candidate I tried to carefully word the request without bluntly stating the situation. I advised that one of his major premises was incorrect, and asked him to research this. • He did. He even spoke to a “very senior Licensed Surveyor”, and responded back that I was wrong. But he would be grateful to learn more if indeed the Examiner was correct! I am in no way intending to be disrespectful of the candidate, his supervising survey, or the “very senior licensed surveyor” referred to. The situation however highlights the lack of available documented information that all surveyors have at their disposal. Even when we wish to turn to someone with the required knowledge, who and where are they? Think back to what has been excluded in this presentation; tidal boundaries, lakes and islands appearing and/or disappearing! What about land granted to the centre line of a river under the Closer Settlement Act 1938? Where would you turn to find out about any of these? • The field measurements provided by the candidate demonstrate and fully support the lore I refer to in this paper. Unfortunately I am unable to provide photos of the particular water course. • Additionally, subsequent to this I was assisting the Board in discussing with another candidate his rural project at an SRBV Workshop day. His circumstance was also a two line water course, but forming a Parish Boundary. Unsurprisingly to me, there was further “on the ground measured” proof of the lore again. It is great when this stuff continually re-enforces itself, once you know what to look for. A river as Parish Boundary. Note also the 1881 OIC Notation. Consider which bank this refers to This paper is primarily prepared for Cadastral Land Surveyors in Victoria. However, many of the principles are derived from Common Law, whose origins are very old and have been applied in England in countless court cases. Australia inherited these important parts of common law and although the conditions of settlement differ (to the English and between Australian jurisdictions), analogies to English court decisions are often brought forward in our own legal cases determined by the courts. Our Resposibility • As Licensed Surveyors we have a very high responsibility to the cadastre, both now and in the future. • Our decisions as to the location of boundaries rest with us for life. • No one else can be blamed if we make a blue. • The impact does not diminish with time alone. • Ignorance of either the LAW, or LORE, is not an excuse. • The statute of limitations does not eventually protect us. • We are responsible. • Paraphrasing the second point, “Our decisions as to the location of boundaries” impact those boundaries for ever! The number of learned people “examining” our work at Land Registry has diminished over the years. No longer are small (or large) errors in the determination of natural water boundaries likely to be found and hence ”stopped” to await discussion and correction. It is, and will continue to be, up to us to get it right. It is our responsibility to know and enforce the common law principles relating to water boundaries that both the English and Australian courts have made determinations on. The following is extracted from the Victorian Survey Practice Handbook, and is worth quoting again. “As was pointed out in the United States by Mr. Justice Cooley as long ago as the 1880’s, the role of the professional man carrying out any cadastral survey is at least partly a judicial one. This may not be apparent at first site, but reflection will show that what a surveyor has to do, in such an operation, is very similar to the task of a judge. He has to gather and assemble pieces of evidence, not all of which are mutually consistent with each other, and has to come to a final decision as to what the facts are.” We are charged with the responsibility of gathering ALL pieces of the evidence, then determining and presenting the FACTS. I wrote the following several years ago as being one of the principles I adhere to in applying my professional judgement. The position of a peg I place is my best attempt to put it exactly where my opinion of its true position should be. This opinion should be well thought out as a court of law may require me, as a Licensed Surveyor, to defend both my opinion of its true position AND the position I have actually placed it. Some water boundary history Peter Knights in his paper dated October 1996 provides us with excellent references and information relating to both the 1881 Order in Council and the 1905 Water Act. Specifically he discusses the Public Purposes Reserve set aside in the 1881 OIC and the clarifications of the term “bed and bank” of a water course. Peter’s research and knowledge of the practices of early and older surveyors is invaluable, and is relied upon to provide the lore referred to in this presentation. Rob Lungren in his paper dated June 1992 gives us an excellent summary of many relevant factors relating to the adoption of a water course as a boundary. He also gives us a snapshot of Titles Office examination assessments and processes from that time. For the purposes of this paper I quote part of his second paragraph. “The early grants with a natural boundary could either show dimensions to the water’s edge or to the centreline of the body of water.” Subtle it is, and often not appreciated, but this little known difference is what caused the production of this paper. I would like to add to Rob’s description and have it read as follows: “The early grants with a natural boundary could either show dimensions to the water’s edge (or bottom bank), the top bank or to the centreline of the body of water.” This is another piece of lore. What Matters – Or Not • It matters that the land grant had the watercourse as a direct abuttal (or went to the centreline). • It is not relevant whether the land was alienated as General Law land (prior to 2nd October 1862), alienated as Torrens Title, or remains as General Law land today. • It is also not relevant if a Crown Allotment has previously been subdivided, although the Licensed Surveyor will need to investigate thoroughly the date of subdivision(s) and what was applied to the dimensions and area at the time of subdivision. • It doesn’t matter when, or to what boundary, the land on the other side of the water course was alienated. The opposite side may be alienated after the 1881 OIC, but the side under survey still has the principles referred to here, apply. • It is important that the natural water boundaries referred to in this paper are Crown Boundaries only. Any natural water boundary created in a Plan of Subdivision has differing characteristics that do not form part of this paper. See Rob Lungren’s paper for further detail. • If the water boundary is to a lake then generally regard is taken to the position of the bank “at the time of the Crown survey for the purpose of alienation”. This paper does not attempt to describe the issues relating to a water boundary defined by a non-tidal lake. A subject for another time! Ad medium filum aquae. This is the Latin term literally meaning the centre thread of water. For land alienated prior to the 1881 OIC, this rule generally applies. For land alienated under the General Law system (prior to 2nd October 1862), this rule will apply. LAWS & THEIR EFFECTS 1881 Order in Council This had the effect of reserving corridors of public land along about 280 watercourses and tributaries in Victoria. Where land had been previously alienated, this Order had no effect on those grants. The crown reservation is offset (eg. 150 links) from the high bank, NOT the bank referred to in the Water Act 1905 (and subsequently the Land Act 1958). A note on the parish plan about crown reservations along the banks of watercourses may not apply to the land you are dealing with. Do research. See Peter Knights paper. Water Act 1905 Section 5 of this Act “resumed” the land covered by the bed and banks of all watercourses that formed a boundary of an allotment, deeming that land to be crown land, as if it had never been alienated. This Act was retrospective. This is now enshrined in Section 385 of the Water Act 1958. The definition of “bed and banks” here is the wetted perimeter. This therefor refers to the low bank. This did not apply to watercourses within allotments, if it was not a boundary. Sections 6 & 7 provided that affected owners shall retain the rights of ordinary use of the water, and access to the water (amongst other matters). See Rob Lungren’s paper. Showing a creek as a boundary and a creek passing through a parcel which is not a boundary Banks It is seen therefor that there are two different banks being referred to in two different pieces of statute. It is imperative for the surveyor to correctly differentiate between the two. Property Law Act 1958 In particular surveyors need to be familiar with, and know how (and when) to apply, Sections 267 to 273. Along a watercourse the centreline may have once been a crown boundary, maybe the top of the bottom bank now is, or maybe a line offset from the top bank is the crown boundary. What about the effect of the doctrine of accretion on each of these boundaries? As licensed surveyors we have been entrusted with a great privilege in making determinations of Crown Boundaries. With that privilege rests a responsibility. Common Law or Case Law Both English and Australian precedents and court cases have application in the determination of natural boundaries. Written documents on the doctrine of accretion and past papers by respected people should also be considered in attempting to make a decision as to a water boundary. Note that the common law relating to water boundaries applies to both General Law land & TLA land. In Barrie Bremner’s paper of 1991 he cites some “Historical Quotations and Court decisions”. Some of these are worth repeating here. Note that these are NOT Barrie’s quotes, but from court decisions. • “The object of all retracement surveys is to follow the footsteps of the original surveyor and relocate the lines as originally run. The purpose is not to determine by measurement where the lines ought to have been established, but to determine where they were in fact originally established.” NLB comment: The above was quoted in particular referring to crown boundaries and the location of either monuments or occupation. However I see it as equally important in the determination of natural water boundaries. We must be historians and researchers. • “Where a boundary is described by metes and bounds (including a plan presentation), the evidence of the bounds, generally speaking, prevails over that of the metes where the two are inconsistent.” NLB comment: Note that a mete is a stated distance in a stated direction. A bound is generally a physical object (natural or man made), such as a river, mean high water mark of the ocean, mountain range, (or more commonly, a survey peg). • “The Courts have established precedents granting priorities of weight where any two or more of the following boundary features present conflicting evidence in the hearing of a dispute. These are, in order of priority: • natural boundaries; • monumented lines; • old occupations, long undisputed; • abuttals; • statements of length, bearing or direction.” NLB comment: This reinforces our responsibility to correctly determine a river boundary. The ground/field survey is the easy bit, the understanding of the history and the correct application of that field survey are crucial. A good spot for a creek traverse on a hot day. Better than blackberries. Some surveyors may wonder what to do when a boundary does not meet the natural boundary “square” or at nearly right angles. This is an extract from The Australian Law Journal – Vol. 41 of April 1968. It specifically relates to rivers and creeks, but elsewhere in the article it details shoreline boundaries. They have the same principles applied as for creeks. These extracts from the Australian Law Journal demonstrate how legal precedents are established by the Courts. They also provide extremely interesting reading. I recommend all surveyors obtain a copy and read this article. It is an invaluable resource. If you have the opportunity to locate and read the entire article by J. E. Moore it also highlights the high esteem that Licensed Surveyors were once held in by the legal profession in 1968. Not sure they see us in the same light today, and pretty sure that it’s mainly our fault, not theirs. CASE STUDY The Bed and Bank Photographs of the actual creek abutting the subject land are unavailable. However I have seen two photographs of the particular creek immediately to the north and south of the subject land, and looked at aerial imagery. From these and the following notes I was able to “paint a picture” of the creek in my mind. In the candidates Field Cards and Surveyors Report the following important factors and comments relating to the creek were recorded. • The creek’s banks were clearly described as being well defined with an obvious vertical “drop” into the water, together with the amount of water flowing and its speed and the materials making up the bed. • Existence of flood damaged fencing. • A higher second bank 3-4 metres back from the water’s edge. Another note in the Field cards about this bank said “falls away quickly”. • An absence of abrupt creek movements. Some other factors I like to see noted in the field cards/book are information about adjacent trees, bushes and grasses (type, typical longevity, approximate age), soil type, erosion and discolouring around roots of trees (this may suggest how long they have been there, and how imperceptible erosion may be occurring), height of the bottom bank (how much undercut will it tolerate), presence of rocks, the presence, if any, of an alternative bed that may exist along a different alignment to the current bed, and is that “other” bed an original normal flow path or an overflow path, litter deposited on nearby fences and in trees by flood waters gives an indication of the potential severity, and hence stability of the bank, stock tracks (for drinking, wallowing, crossing), manmade crossings (could be up or down stream and cause an effect), dams (not only of the creek but small tributaries providing an alteration to the surface flow into the main stream), and any other circumstances. Whilst at the creek look at the old crown surveys and see what has been noted regarding these factors. Are there differences or does it seem similar to what was previously described. In all cases try and have a yarn with the farmer, and/or his neighbours. Ask pertinent questions to get them going, maybe about the regularity of floods, what damage did they notice? Photographs provide an invaluable source of information, especially when back in the office trying to piece together and explain something that doesn’t quite fit properly! All of these paint a picture and provide an estimated timeline of possible bank movement. These factors together with the field pick up of the bank contribute to your final adoption of the bank, or otherwise, as the boundary. The following has been ‘cut and paste; from my report to the Surveyors Registration Board of Victoria, obviously with alterations, but also with some additions. • In my requisition I tried to have the candidate investigate further the impact(s) (if any) of the 1881 OIC and Section 5 of the Water Act 1905 upon his land. In requiring this I hoped he might question the meaning of the two line creek that is shown on the Parish Plan (M259(5)). He had stumbled on a bit of a tricky one in this Project, and I was searching for his understanding of this. He has undertaken some research (a search of the Crown Grant dated 1854, a reading of §5 Water Act 1905 and §385 Land Act 1958 and talked to “a very senior licensed surveyor” – no name provided), but been unable to correctly assess the information and apply it in the situation he encountered. • As stated above his situation relates to lore as well as law, and the Rural Cadastral Project process is a forum that knowledge can be offered and passed on by Examiners and Board members. I don’t believe that the situation of the candidates parcel is explained in any OSG or SRBV publications. Peter Knight’s paper “Rivers and Their Impact on Cadastral Boundaries” does provide us with an insight and an opinion as to where Crown Surveyors of the time may have measured to. The following relates to: • Land alienated prior to the 23rd May 1881 Order in Council. • A “two line” creek or water course is shown on the Parish Plan. And often the “Put Away” Plans. • The relevant part of that two line water course does not form the parish boundary. (A different meaning is applied when a two line water course forms a parish boundary. Not applicable to this discussion.) • Non tidal water courses, lakes and pools • This is a different situation to a “single line” creek or water course that fulfils each of the other conditions listed above. • Also note that the land on the “other side” of that two lined water course may have been alienated either prior to or after the 1881 OIC. It doesn’t matter. However in this case it was actually alienated in 1854, hence it too went to the centre thread of the creek. In preparing this report I have had another discussion with Peter Williams (whose water boundary knowledge I very highly regard, together with his vast experience of lore), and also requested the OSG to look for any old survey records, particularly the Put Away Plans. This assistance is greatly appreciated and respected. At Common Law it is known that land abutting a non tidal watercourse or pool, granted with a direct abuttal, has the natural boundaries determined by the common law rule of “ad medium filum aquae” (the centre thread of the water). The application of this rule applies even without being stated specifically in the deed or title. For this to not be the case it must be expressly denied in the Grant of land (very rare, if at all). The subject land was granted in 1854 and the grant does not expressly deny the rule, so the rule of ad medium filum aquae applies. The issue here is not whether the land was granted to the centre line (that is a fact as can be seen by inspection of the Crown Grant deed), but rather what do the dimensions in that Grant (and the Parish Plan) apply to, and mean. The existence of the “two lined” creek on Parish Plan M259(5) in this case acts as a trigger or clue. These circumstances exist as the dimensions (distances along boundaries intersecting or “hitting” the water course) do not go to the centre line, but rather the near bank. Many years ago Peter Knights advised me that after much investigation of old field books he found that the old field surveys for early Land Sales surveyed to the near bank only. They did not survey to the centre line. This was also supported in later years in discussions with Kevin Bourne and Geoff Westcott, both from the Titles Office. In this way, similarly the land on the “other side” of the water course was also surveyed to its near bank, so that the survey draftsmen or cartographers were able to directly plot each bank of the water course. We already accept the very high standard of draftsman-ship on Parish Plans, so it is not surprising to accept this too. We can note that in these circumstances we do actually see lines that are not parallel (maybe indicating pools) and also islands which are indicative of actual surveyed lines. This knowledge is LORE. But. Let’s not be satisfied with only looking at the latest Parish Plan. Let’s also look at the Put Away Plans. M258(3) shows the creek as a single line creek abutting the subject land. Very interesting! It is shown as a two line creek northwards across the Government Road and CA 21 and a two line creek as it abuts CA 23. Similarly this is how M258(1) also depicts the creek. Is the creek simply narrower in this region? We will possibly never really get to the bottom of why the plots changed, so we need to assess the field data against our experience (lore). Somewhere and somehow the single line creek became drafted as a two line creek. At this stage we are unable to precisely determine what this means, but the trigger has been cued, and our interest certainly raised. So do the dimensions go to the centre line or the bank? To determine this some more lore is required, together with the facts supplied in the field survey (more of that later). But we need to remember that possibly the bank was surveyed to. Now the question remains; which bank? Peter Knights gives us an opinion in the paragraph (of his 1996 paper) after his first “cross section” showing banks A and B. He states “From a study of many surveys over many years, it is my belief that the top of the high bank (point labelled “B” on the sketch) was the origin from which ….. Crown Surveyors…” Whilst this statement relates to reserve boundaries, it provides us with an appropriate insight into the methods of Crown Surveyors during the 1800’s. These methods would be based upon direction of respective SurveyorsGeneral. And also expediency to facilitate the early Land Sales. Peter’s experience and research should not be taken lightly, nor discarded without strong contradicting evidence. Applying Peter’s many years of research, and many years of my own experience, I believe that often the dimensions shown in Crown Grants and on Parish Plans were measured to the top or high bank. Exceptions do occur (and the 1850’s preceded the 1881 OIC by a considerable amount of time), and due to the ambulatory nature of a water course, we are required to rely on this historical and anecdotal evidence. That’s cadastral surveying. And it’s fun! This knowledge is lore. Section 5 of the Water Act 1905 effectively “resumed” the bed and banks to be the property of the Crown as if they had never been alienated. Sections 6 & 7 of that Act provide that affected owners shall retain the rights for ordinary use of the water, and access to the water (amongst other matters set out in those sections). This is law. If a titles’ dimensions therefore went to the centre line of the water course (a single line creek), then §5 would have had the effect of reducing the length of any intersecting boundaries (by half the width of the water course) and reducing the area (by half the average width x the length of abuttal to the water course). It is important to note that §5 is clear in stating that the bed and banks are deemed “not to have passed with the land so alienated”. In practical terms this means the land is still considered as a whole Crown Allotment (not a part crown allotment) and as such the bank is deemed to be the Crown Boundary. That is why the Surveyor General can make rulings on the position of these ambulatory boundaries. That is also why our plan heading describes the land as a full Crown Allotment, not Part. This the effect of the law. This sketch demonstrates this circumstances where the distance is to the centre line of the water course. If the dimensions of the intersecting boundaries in the title are to the top bank (not the centre line), as proposed in the examples of two line creeks, of the water course then Section 5 of the Water Act 1905 had no effect on the boundary dimensions or area. The effect therefore of §5 in these cases is only that no longer can the rule ad medium filum aquae be applied to the title. The effect on the rights of the land (or owners) to the water (and access) does not differ whether the dimensions were originally to the centre line or bank of the water course. This the effect of the law. This sketch demonstrates this circumstances where the distance is to the top or high bank of the water course. In the subject circumstance the dimensions of the title are possibly to the top bank (we probably have a two line creek). Section 5 of the Water Act 1905 resumed the land from the centre line to the bottom bank. The right of the land owner to the “strip” between the top bank (determined by dimension in the Grant) and the bottom bank (determined by statute) is not diminished in any way by these circumstances. The boundary of the land remains as the bottom bank determined by the passing of the Water Act 1905. So we now need to assess the survey data to give us guidance as to what the original dimensions actually pertain to. In the absence of any substantial ambulatory movement in the water course (relatively stable banks reported by the candidate) we could therefor expect to find an increase (compared to the Grant) in the length of the boundaries intersecting the water course if the dimensions were originally to the bank. That is, the difference between the top and bottom banks, as this land should now be included into the surveyed dimensions. What does the candidate’s data on his Plan and Field Records provide us? Bingo! Longer it is. • Northern boundary: Deed/Title = 346·01m, Survey = 347·56m • Southern boundary: Deed/Title = 299·54m, Survey = 302·52m This is the effect of both LAW and LORE. In looking at the two photographs the candidate originally supplied (these were adjacent to the north and south, not of the subject land) the amount of this difference appears to be in line with the situation on the ground. Also, the candidate himself recorded a higher bank about 3-4 metres back from the waters edge. We can therefor conclude with some surety that the original Crown dimensions were not measured to the centre line, but rather the bank. In particular the top or higher bank. This adds to the wealth of experience in accepting lore as a valuable and relevant source of information. IMPACTS ON LICENSED SURVEYORS • It does not matter if the Licensed Surveyor is undertaking a full survey, partial survey or non-survey plan. He must do the appropriate research of the title and situation. • If a creek traverse is not being undertaken, and new boundaries and lots are nowhere near the creek, the plan must still display the correct area of all lots including the balance lot, whether surveyed or not. A balance lot (with the watercourse) must be adjusted in area and dimension based upon the original crown grant dimensions and area. • If the dimensions went to the centreline, then the area was derived from those. Half the width of the stream over the length abutting the land, must be deducted from the title area. • If the dimensions went to the top bank, then the area was derived from those. The average distance between the banks over the length abutting the land, must be added to the title area. • If we get this wrong, the cadastre, subsequent land owners and any mortgagors are compromised. The Licensed Surveyor is responsible for his or her work. For ever. AVAILABLE RESOURCES • • • • • • • • • Survey Practice Handbook, SRBV Rivers and Their Impact on Cadastral Boundaries, Peter Knights October 1996 River Boundaries, Robert Lungren & Peter Knights 1992 The Australian Law Journal Vol. 41, J. E. Moore April 1968 Principles of Re-establishment Guidance Note 6, Victorian Government The Doctrine of Accretion, Victorian Government, 1993 Is the Fence a Crown Boundary, Barrie Bremner 1991 At the Seaside, J. D. Sherwood, August 1976 Hallman’s Legal Aspects of Boundary Surveying as Apply in New South Wales, circa 1994 Not all of the above are readily available on “surveying” websites. I have some of these stashed away in good old paper format in an old envelope. A drafter during an office clean up once, labelled it “Neville’s Old as the Hills Stuff”. What else is out there stashed away in your old folders that can help us all? I for one would like a copy.