Enfranchisement - Fairweather Stephenson

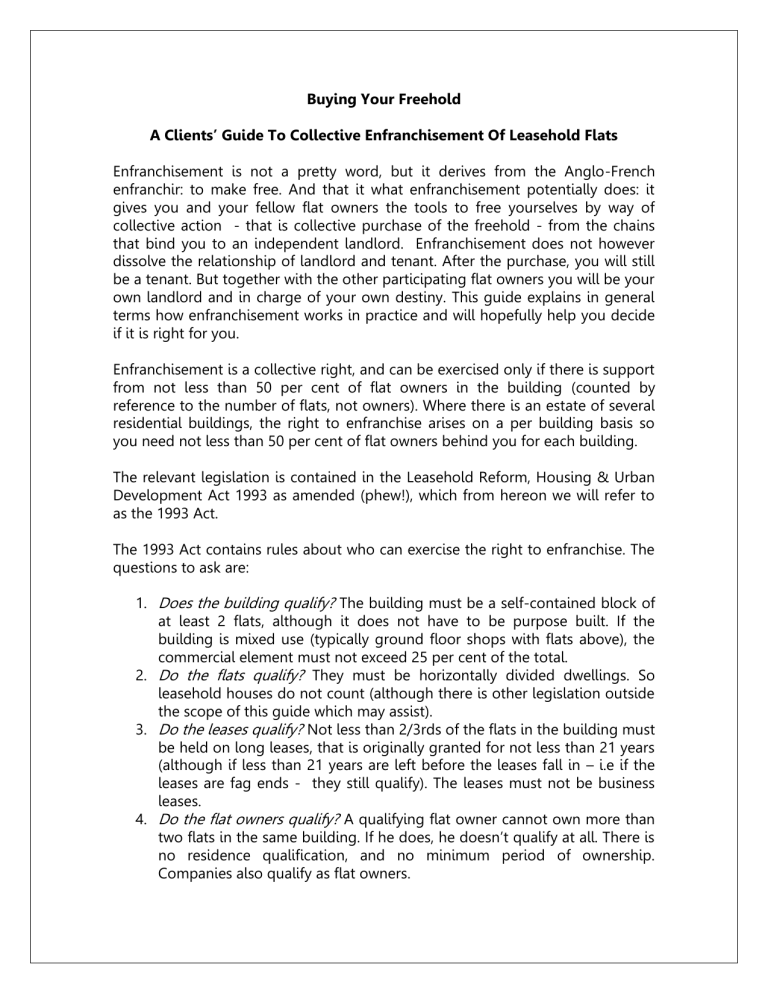

Buying Your Freehold

A Clients’ Guide To Collective Enfranchisement Of Leasehold Flats

Enfranchisement is not a pretty word, but it derives from the Anglo-French enfranchir: to make free. And that it what enfranchisement potentially does: it gives you and your fellow flat owners the tools to free yourselves by way of collective action - that is collective purchase of the freehold - from the chains that bind you to an independent landlord. Enfranchisement does not however dissolve the relationship of landlord and tenant. After the purchase, you will still be a tenant. But together with the other participating flat owners you will be your own landlord and in charge of your own destiny. This guide explains in general terms how enfranchisement works in practice and will hopefully help you decide if it is right for you.

Enfranchisement is a collective right, and can be exercised only if there is support from not less than 50 per cent of flat owners in the building (counted by reference to the number of flats, not owners). Where there is an estate of several residential buildings, the right to enfranchise arises on a per building basis so you need not less than 50 per cent of flat owners behind you for each building.

The relevant legislation is contained in the Leasehold Reform, Housing & Urban

Development Act 1993 as amended (phew!), which from hereon we will refer to as the 1993 Act.

The 1993 Act contains rules about who can exercise the right to enfranchise. The questions to ask are:

1.

Does the building qualify? The building must be a self-contained block of at least 2 flats, although it does not have to be purpose built. If the building is mixed use (typically ground floor shops with flats above), the commercial element must not exceed 25 per cent of the total.

2.

Do the flats qualify? They must be horizontally divided dwellings. So leasehold houses do not count (although there is other legislation outside the scope of this guide which may assist).

3.

Do the leases qualify? Not less than 2/3rds of the flats in the building must be held on long leases, that is originally granted for not less than 21 years

(although if less than 21 years are left before the leases fall in – i.e if the leases are fag ends - they still qualify). The leases must not be business leases.

4.

Do the flat owners qualify? A qualifying flat owner cannot own more than two flats in the same building. If he does, he doesn’t qualify at all. There is no residence qualification, and no minimum period of ownership.

Companies also qualify as flat owners.

5.

Is the landlord exempt? Private landlords are not exempt, with one exception. If the building is a conversion of not more than 4 flats and there is a resident landlord who has owned the building continuously since before the conversion, then the right to enfranchise does not apply.

It gets complicated with hybrid spaces such as live work units. For example, the unit itself may qualify – because it is structurally adapted for use as a dwelling.

But the leases may not if they are business leases.

What are the advantages of enfranchisement for flat owners? There are two main ones as follows:

1.

Protection of the value your investment. A lease is intrinsically a wasting asset, every year a little bit more is nibbled off the value as the lease period diminishes. If the flat owners collectively own the freehold, they are able to extend their leases to virtual freeholds and so escape from this vortex of ever accelerating loss. One insidious feature of leases is that the bit nibbled off is slightly bigger each year. So, if for example the lease has

125 years to run then knocking a year off the lease period will have a minimal effect on value. But if the lease has only 2 years to run, then 12 months later all things being equal it will halve in value. There are two watersheds with the length of leases. If the remaining length of lease falls below 80 years, then the price increases significantly because you have to pay what is known as “marriage value.” And at less than 50 years, leases become increasingly difficult to mortgage because lenders are anxious that the value of their security may not be sufficient to repay the loan in the event of default. A vicious circle then sets in: lenders won’t lend on the flat, which reduces its marketability, which reduces its value… and so on.

Similar considerations apply if your ground rent is subject to review, particularly if the review is frequent and/or linked to retail or consumer price inflation and/or linked to the capital value of the flat. If you’re heading towards a significant increase in your ground rent at the next review, that may well depress the value of your investment as well as taking money out of your pocket to pay the rent.

Note that, as an alternative to collective enfranchisement, you can substantially protect the value of your investment by exercising your statutory right to a lease extension. This takes effect as a surrender of your existing lease and grant of a new one for an additional 90 years at a peppercorn rent. (For a discussion of the comparative advantages of collective enfranchisement and statutory lease extensions, see further below).

2.

Control. If you and other flat owners collectively own the freehold of your building, you have control of your environment. You can collectively decide: the level of service charges, what repairs to do, who to insure with, whether you need managing agents and if so who it should be. Above all, you are best placed to ensure that your building is maintained to a high standard and that you secure value for money in the provision of services.

If your building is already managed by a tenant controlled management company of which you are a member or a Right To Manage company, then buying the freehold will not increase your control to the same extent. But it may still assist, if for example your landlord has the right to nominate your insurer. And it may also protect your environment from exploitation from your landlord, for example by way of new building, anti-social use of non residential space, installation of telecoms masts and so on. (For a discussion of the comparative advantages of collective enfranchisement and setting up an RTM company see further below).

Are there disadvantages? There may be. Once you’ve bought the freehold, then someone has got to put in the time effort to manage the building. Even if you appoint managing agents, you will be surprised how much time this takes. In nearly all cases, you find that just two or three people overwhelmingly shoulder the burden and the rest enjoy a free ride for which they show scant gratitude. For better or worse, that seems to be human nature. And if you fall out with your neighbours over issues such as service charges, anti-social behaviour, plans for improvements and goodness knows what else, things get personal. An independent landlord can also a convenient bogey man. Not so good if the director of the new landlord company is living right next door. There also seems to be a one man awkward squad in every building. If there’s an independent landlord, they’re the landlord’s problem not yours. As and when you take over, their baggage of paranoia hostility and aggression may be turned on you.

So, what are the first steps? The first steps are exploratory, and to some extent go hand in hand.

1.

Calculating a back of the envelope ball park estimate of cost. There are in fact two elements to this question. First, what is a reasonable estimate of the total cost (something the organisers need to know). And secondly, what is the cost per participator (which is the question that everyone else will ask).

There are three elements to the total cost of the exercise, which are:

1.1

The costs which you incur to acquire the freehold, typically the fees of your specialist valuer and solicitor. Stamp Duty Land Tax is not usually payable.

1.2

The landlord’s reasonable and proper professional costs. These include the fees of the landlord’s valuer and solicitor, but not costs which the landlord incurs in tribunal proceedings if there is a dispute about the price or other terms of acquisition.

1.3

The purchase price of the freehold. You will need a specialist valuer to give you an accurate valuation. But there are on line calculators that can get you going and give you a ball park figure for initial discussion purposes.

One such calculator is at: http://www.lease-advice.org/calculator/ .

There are two main elements to the valuation. The first is the present value of the freehold with vacant possession, deferred until expiry of the leases. The key figure for this is the deferment rate i.e the annual rate by which the present value of the freehold is discounted over the remaining lease period. The lower the deferment rate, the higher the price you will pay.

The second element is the capitalised value of the right to the ground rents for the remaining lease period. Here the question which the valuer is asking is: how much would an investor pay for that income? Much will depend on whether there are rent reviews, and if so the type of review.

Here, the key figure is the capitalisation rate. Again, the lower the rate, the higher the price. The capitalisation rate tends to track interest rates on government bonds. If interest rates are low, they drag down capitalisation rates and push up asset values, and vice versa.

You should also allow a significant contingency for the unexpected, 35 per cent would not be unreasonable. A small adjustment in the deferment rate

(see above) can have a very significant effect on price. And professional costs should include contingencies, for example for the costs of a tribunal application if the price or other terms of acquisition cannot be agreed with the landlord.

The cost per participator however is likely to depend on how much support you have.

2.

Finding out how much support you have. You need to establish if you have enough support to get you over the 50 per cent line. It’s not difficult to see however that the more flat owners who will join in the purchase, the lower the cost per participator (unless you bring in investors). You will not be able to provide a reliable cost per flat owner until you know how many are willing to take join in. The more the better. You are likely to find however that a significant number of flat owners will want to see a professional presentation and will want their questions answered before

they will sign on the dotted line. But you will probably not be able to answer their key question – how much is it going to cost me – until you have a reasonably reliable idea of how many flat owners are willing to take part.

3.

Collecting some seed corn funds. You are likely to need initial advice from a specialist valuer and solicitor. This is probably going to cost between

£2,500 plus VAT and £5,000 plus VAT. Try asking interested flat owners for say £250 and £500 on a non-returnable basis to get the ball rolling. If they’re willing to make a small initial investment, there’s a good chance they will support you.

If you think you have or may have enough support and the price looks affordable, then the next steps involve organising that support into a fighting force to take on the landlord.

Here the stages are as follows:

1.

Obtain a professional valuation from a specialist valuer, preferably one with experience of arguing their case before the First Tier Tribunal.

2.

Appoint a solicitor. Again this is a specialist area of work. If the solicitor doesn’t have relevant time limits (see below) at his fingertips, he’s not for you.

3.

Organise a meeting of flat owners at which your professional team can give a presentation and answer questions from flat owners. From that meeting, set up a steering group of flat owners with an informal mandate from flat owners collectively who will see the process through and become the first directors of the purchase company (see below). Try to put together a team with relevant professional skills: surveyors, accountants, actuaries and even lawyers are all good people to have on board.

4.

Agree the basic terms on which flat owners can join in the purchase. This is normally formalised in what is known as a participation agreement, which contractually commits flat owners to the exercise. If it’s a small building and everyone gets on well, this may not be necessary and after all you’re hardly likely to want to sue one of your neighbours if they change their minds about joining in. But there should still be agreement in principle about what is expected of everyone, and for tax reasons it is important that there is a contractual bargain in respect of lease extensions

(see below). Here are the parameters of the main issues you need to agree for the participation agreement:

How is the purchase price to be divided between participating flat owners? The obvious answer is that everyone should contribute equally. But is that fair? If the ground rents vary between flats and you intend to cancel ground rents after the purchase, there is a difference in the potential financial benefit between flat owners.

Similarly, if you intend to extend the leases after the purchase in circumstances where the flats vary in value because of size, position and so on the likelihood is that the more valuable flats will benefit disproportionately from the purchase. In some cases, an equal division of the price is sufficiently fair. In others however, there is a good case that the financial burden should be proportioned in accordance to benefit.

How are costs including landlord’s costs to be divided? Even if the purchase price is divided according to benefit, there is an argument that costs should be divided equally in any event.

Is there to be a cap on contributions? Flat owners will often want the assurance that, unless they agree otherwise, their contributions will not exceed a specified sum.

How are “contributions” of non-participating flat owners to be funded? Are they to be shared equally between the participators, or offered to investors?

What are flat owners to get in return? In most cases, the deal is that in return for their financial contribution, flat owners receive extended leases and cancellation of ground rents. It is important for tax reasons that this is recorded as a contractual bargain, otherwise your purchase company may find that the lease extensions and ground rent are treated as taxable disposals and participating flat owners are taxed on dividends in kind or (if also directors) benefits in kind.

5.

Set up a company to act as the flat owners’ special purpose vehicle for the purposes of the purchase. This company – the right to enfranchise company – will be the collective instrument of the flat owners in their purchase. It is the company which will buy the freehold. Participating flat owners will become shareholders in the company. Again, there are decisions to be made about the internal rules (articles of association) of the company:

Is each participating flat owner to have a single share, even if they pay in different amounts of money? Or are the number of shares allotted to each flat owner to be proportionate to their financial contributions?

Will the share attach to the participant’s flat, or can it be transferred

- or even sold - independently of the flat?

If there are investors, will they also be shareholders and if so will they have preferential rights to dividends? (An alternative is that investors lend money to the company and in return by way of interest they receive the ground rent from the leases of non participating flat owners).

Can anyone be a director, or should directors be chosen only from shareholders? In small buildings, you may wish to say that all participating flat owners are entitled to be directors.

Will directors be paid? (Usually not!)

What rules will be put in place to control conflicts of interest? (For example can someone be elected as a director even if they haven’t paid their service charges?).

6.

Finalise the suite of documents, namely:

the participation agreement;

the constitution of the right to enfranchise company;

(optional) informal prospectus, which explains the benefits costs and risks of enfranchisement to flat owners

(optional) FAQ’s. The sort of questions that flat owners typically want answered are: o how much will it cost me? o will there be a cap on costs? o will it increase the marketability/ value of my flat? o what will happen if I don’t take part? o what will happen if I sell my flat before the freehold purchase is completed? o will I get my money back if the purchase doesn’t go through? o who will hold funds before they’re spent? o how long will it all take? o what can go wrong? o what happens if we cannot agree the price with the landlord? o will we still be tied in to the landlord’s managing agent? No is the answer to that one.

Several of these questions however – especially about costs and timescales - are not amenable to precise answers, but it is usually possible to set out the parameters.

7.

Arrange a second meeting of flat owners and the professional team at which the suite of document are presented. This is the moment at which flat owners should be asked to sign up to the participation agreement.

And once you have 50 per cent support, you’re in business…….

Then what happens? Your solicitors will already have given advice, attended meetings and probably drafted your suite of documents. Now they have responsibility for the process going forward. They will – and this is only the briefest summary:

1.

Check the identity of the landlord and flat owners from Land Registry records;

2.

Obtain ID for each participating flat owner for money laundering purposes;

3.

Draft the initial notice. This is the notice which sets the process in motion with your landlord. The notice states your intention to purchase, and sets out your opening offer. Your opening offer will not usually be your final offer, but it must be a realistic price – otherwise there is a risk that your notice will be found to be invalid. As well as the building, the notice should also identify the other land and structures that you may want to acquire and which benefit flats in the building - for example car spaces, communal gardens, backyards for dustbins and external accessways. The notice has serious legal consequences:

It sets the valuation date for valuation purposes. So if property prices are going up quickly, you won’t want to waste time and you’ll want to serve the initial notice as soon as possible. If prices are falling however, you may want to hold off (although perhaps not if a rent review is imminent, or delay might compromise the value of the leases to the landlord’s benefit).

If the notice is withdrawn or deemed to be withdrawn, you can’t serve another one for 12 months. (Invalid notices are however an interesting grey area, and seemingly do not necessarily preclude serving another one before the usual 12 month “ban”expires).

The notice triggers liability for the landlord’s reasonable and proper costs. Do please note that you and the other leaseholders are liable even if you subsequently withdraw your notice and whether or not you complete your purchase.

4.

Either obtain the signature of each participating flat owner on the initial notice, or obtain their written authority to sign it on their behalf. Written authority is usually preferable.

5.

Serve the notice, and protect it by registration of a unilateral notice against the landlord’s title. If a unilateral notice isn’t filed, the initial notice is not binding on the landlord’s successor in title if the landlord transfers the freehold to someone else.

6.

Check the validity of the landlord’s counter-notice. The landlord has two months to serve a counter-notice, failing which the RTE company can apply to court for the court to determine the terms of acquisition. The counter-notice will tell you how much the landlord thinks you should pay

(take a deep breath before reading). Note that a counter-notice will still be valid even if the landlord’s price is outrageous.

7.

Hand over the negotiations to the valuers. In most cases, they will be able to agree a price. Most of the specialist valuers doing enfranchisement work know or know of each other, respect each others’ opinions and can do business with each other.

8.

If the valuers can’t agree, then the solicitors must subject to your instructions apply to the First Tier Tribunal (Property Chamber) for a determination. There is a six month deadline for this application, calculated from the date of the counter-notice. Diarise it!

9.

If the terms are agreed or determined but the landlord fails or refuses to sign the transfer, the solicitors must – again subject to your instructions – apply to court for a vesting order i.e. an order by which the court in effect signs the transfer on the landlord’s behalf. There is a four month time limit, calculated from the date of agreement or determination. Another date to diarise.

10.

Draft the transfer and complete the purchase on your behalf. At completion, the solicitors will wish to ensure that unallocated service charge funds and reserves are paid to you, as well as advance payments of ground rents (for periods after completion). The landlords or their managing agents should also provide a closing account of rent and service charges. There are often niggles, for example over historic service charge arrears and on-going service contracts.

11.

Complete an SDLT return (although in the normal course of events SDLT will not be payable) and register the transfer at the Land Registry.

12.

If appropriate, issue new leases to participating flat owners.

If you get to that point, congratulations. Buying a freehold is a serious endeavour, and is likely to require more time effort and commercial acumen than you expect.

There are however other options, as mentioned above. These are:

1.

Buying a statutory lease extension. This is an individual right, not a collective one. So, if your main objective is to protect the value of your investment and you do not have the support for collective enfranchisement, then a statutory lease extension may well be for you. A purchase price of a lease extension will usually be less than a share of freehold, because you are only buying an additional 90 years – not buying out the freehold to the end of time. But the professional costs including landlord’s costs will usually be higher, because you are not sharing these costs with other flat owners. In a small block, the difference may be marginal. If however, you’re getting together with say 100 other flat owners the difference in your costs contribution will be significant. A lease extension does not of course increase your control over the building, but that may not matter if the building is managed by a tenant controlled flat management company or a Right To Manage company.

2.

Setting up a Right To Manage Company. This doesn’t protect the value of your investment. But it does give you collectively with other flat owners

(and the landlord) control over the management of your building. The virtues of Right To Manage are:

You do not have to show that the landlord is at fault;

You do not have pay anything, other than the costs of the procedure to acquire the right.

But you do need 50 per cent support of flat owners. In some circumstances, Right To Manage can be a good starting point before going the whole way with collective enfranchisement. You will at least get the chance to find out if you can work with other flat owners.

We hope you have found this guide helpful. If you have any queries please contact us. Meanwhile, please note that this guide is intended for general guidance only and not as advice in respect of specific circumstances.

![[Date] [Name of Landlord I`m Applying to] [Landlord I`m Applying to](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006797608_2-3bf07d32e3f6a0a58c5d937b12404929-300x300.png)