New Intro Lit 04 Poetry Sound patterning

advertisement

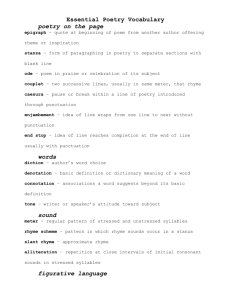

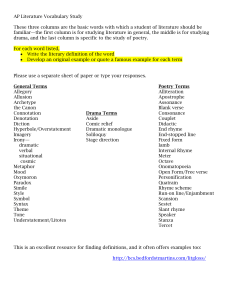

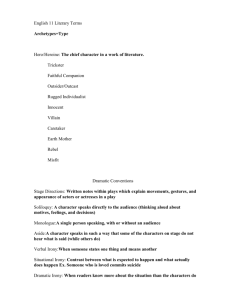

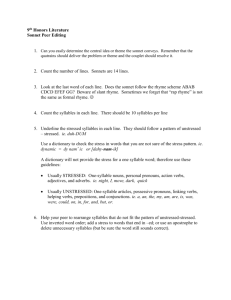

POETRY Poetry and Prose. Sound Patterning. Prosody. Rhymes. Stanza Forms Poetry and Verse Poetry is one of the subcategories of literature along with drama and fiction. In this sense by poetry lyric poetry is meant. Metrical poetry, i.e. verse, differs from prose in that the former is rhythmically organized speech down to the level of syllables, whereas the latter is either orderless or follows ordering patterns other than syllabic principles. Rhythm Prose rhythm may use repetitions, parallels of words, syntactical units, grammar structures, sentence length, semantic structures. Prose rhythm does not follow any preset pattern. Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice (1813) from Chapter 1 It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife. However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered as the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters. ``My dear Mr. Bennet,'' said his lady to him one day, ``have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?'' Austen cont. Mr. Bennet replied that he had not. ``But it is,'' returned she; ``for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.'' Mr. Bennet made no answer. ``Do not you want to know who has taken it?'‘ cried his wife impatiently. ``You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.'' This was invitation enough. Austen cont. ``Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take Possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.'' ``What is his name?'' ``Bingley.'' ``Is he married or single?'' ``Oh! single, my dear, to be sure! A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a year. What a fine thing for our girls!'' Michaelmas Michaelmas, the feast of Saint Michael the Archangel (also the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, Uriel and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a day in the Western Christian calendar which occurs on 29 September. Genesis King James Bible 1: In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. 2: And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. 3: And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. 4: And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness. 5: And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day. Genesis cont. 6: And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters. 7: And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so. 8: And God called the firmament Heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day. 9: And God said, Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear: and it was so. Genesis cont. 10: And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together of the waters called he Seas: and God saw that it was good. 11: And God said, Let the earth bring forth grass, the herb yielding seed, and the fruit tree yielding fruit after his kind, whose seed is in itself, upon the earth: and it was so. 12: And the earth brought forth grass, and herb yielding seed after his kind, and the tree yielding fruit, whose seed was in itself, after his kind: and God saw that it was good. Verse Rhythm or Verse Rhythm Verse is a patterned succession of syllables: some are strongly emphasized, some are not. Rhythms of poetry, compared with prose rhythms, are stylized and artificial, they fall into patterns that are more repetitive and predictable. Verse rhythms call attention to themselves. Poetic Rhythm Literature – coded text Poetic rhythm – concentration and intensity Primordial functions of poetry naming possession healing Incantatory rhythms, verse spells, healing charms (an incantation or enchantment is a charm or spell created using words) An Old English medical verse-spell against poison This herb is called Stime; it grew on a stone, It resists poison, it fights pain. It is called harsh, it fights against poison. This is the herb that strove against the snake; This has strength against poison, this has strength against infection, This has strength against the foe who fares through the land. (Anglo-Saxon Poetry. Sel. and trans. by R. K. Gordon, rev. ed., London: J. M. Dent and Sons, 1954, 93) Verse Rhythm Rhythm is based on orderly repetition. Poetic rhythm is based on the regular alternation of certain syllabic features of the text. Philip Larkin (1922-1985) The Trees The trees are coming into leaf Like something almost being said; The recent buds relax and spread, Their greenness is a kind of grief. Is it that they are born again And we grow old? No, they die too, Their yearly trick of looking new Is written down in rings of grain. Yet still the unresting castles thresh In fullgrown thickness every May. Last year is dead, they seem to say, Begin afresh, afresh, afresh. Philip Larkin (1922–1985) THE TREES The trees are coming into leaf Like something almost being said; The recent buds relax and spread, Their greenness is a kind of grief. Is it that they are born again And we grow old? No, they die too, Their yearly trick of looking new Is written down in rings of grain. Yet still the unresting castles thresh In fullgrown thickness every May. Last year is dead, they seem to say, Begin afresh, afresh, afresh. SYLLABLE A syllable commonly consists of a vocalic peak, which may be accompanied by a consonantal onset or coda. In some languages, every syllabic peak is indeed a vowel. But other sounds can also form the nucleus of a syllable. In English, this generally happens where a word ends in an unstressed syllable containing a nasal or lateral consonant. CV / CVC / VC /CCV / CCVC / etc. Diphtongs, triphtongs – vowel sequences in which two or three components can be heard but which none the less count as a single vowel BUT one syllable: hire, lyre, flour, cowered two syllables: higher, liar, flower, coward Prosody (from Wikipedia) In poetry, meter (metre in British English) is the basic rhythmic structure of a verse or lines in verse. Many traditional verse forms prescribe a specific verse meter, or a certain set of meters alternating in a particular order. The study of meters and forms of versification is known as prosody. (Within linguistics, "prosody" is used in a more general sense that includes not only poetical meter but also the rhythmic aspects of prose, whether formal or informal, which vary from language to language, and sometimes between poetic traditions.) Prosody Prosodic features of speech: Chief phonetic correlates: tone stress / beat /accent intonation pitch duration loudness Pitch is widely regarded in English as the most salient determinant of prominence. When a syllable or a word is perceived as ‘stressed’ or ‘emphasized’, it is pitch height or a change of pitch, more than length or loudness, that is likely to be mainly responsible. Duration The duration of syllables depends on both segment type and the surrounding phonetic context. Duration is also constrained by biomechanical factors: part of the reason why the vowel in English bat, for example, tends to be relatively long is that the jaw has to move further than in words like bit or bet. Stress / Beat / Accent Stress commonly is a conventional label for the overall prominence of certain syllables relative to others within a linguistic system. In this sense, stress does not correlate simply with loudness, but represents the total effect of factors such as pitch, loudness and duration. Stress in English English, sometimes described as a ‘stress timed’ language, makes a relatively large difference between stressed and unstressed syllables, in such a way that stressed syllables are generally much longer than unstressed. Accent The term ACCENT is sometimes used loosely to mean stress, referring to prominence in a general way or more specifically to the emphasis placed on certain syllables. The term ‘accent’ is also used to refer to relative prominence within longer utterances. Stress / Accent The terms STRESS and ACCENT in particular are notoriously ambiguous, and it would be misleading to suggest that there are standard definitions. Beat Beat denote stress with metrical relevance, i.e. stressed syllables which count in metrical lines are called beats. English Versification English poetic rhythm is based on the regular alternation of stressed and unstressed syllables. (Duration and pitch are no metre creating features.) Stresses are that of words stresses and marked in dictionaries by ‘ as in synecdoche /sɪ’nɛkdəkɪ/. Scansion is the act of determining and graphically representing the metrical character of a line of verse. Stressed syllables are marked by the symbols / or –. Unstressed syllables /slacks are marked by the symbol X. Scansion When I consider how my light is spent X / X / X / X / X / (Milton) Whose woods these are I think I know X / X / X / X / (Frost) When my mother died I was very young X X / X / X X / X / (Blake) Scansion Down by the salley gardens X / X / X / X || my love and I did meet X / X / X / (Yeats) ‘||’ is a division marker or bar between repeated units of a line broken into sections by a caesura Rhythm and Metre Rhythm The rhythmic structure of a poem is formed by repeating a basic rhythmical unit of stressed and unstressed syllables Metre Metre grows out of the linguistic rhythms of the words, it is the design formed by the rhythms, it is an abstract pattern. The general metre and the actual rhythm of a specific line are not always identical. Metrical Systems in English 1 Accentual/Stressed Metre In accentual/stressed metre the number of accents/stressed syllables is fixed in a line. However the number of unstressed syllables is variable. In order to define the actual form you have to count the number of accents per line. Metrical Systems in English 1 Accentual/Stressed Metre Old English (Anglo-Saxon) Alliterative Versification The basic metrical feature of the line is four strong stresses: / / / / The spaces before and between the stress can be occupied by zero, one, two or three syllables, e.g. : X / X X / X X X / /, or X X / X / / X X / X, etc. Each full line is divided into two half-lines (hemistichs) by a caesura: X X / X X / || X X / X X / Anglo-Saxon Alliterative Versification cont. The distinctive feature of this metrical form is its alliteration. Alliteration is a figure speech, meaning the repetition of consonant or vowel sounds at the beginning of words or stressed syllables. It is a very old device which often help create onomatopoeic effects, i.e. effects imitating sounds. Alliteration is a key organizing principle in Anglo-Saxon verse. Alliteration Alliteration is the principal binding agent of Old English poetry. Two syllables alliterate when they begin with the same sound; all vowels alliterate together, but the consonant clusters st-, sp- and sc- are treated as separate sounds (so st- does not alliterate with s- or sp-). Anglo-Saxon Alliterative Versification cont. Formal requirements: • A long-line is divided into two half-lines. Half-lines are also known as verses or hemistichs • A heavy pause, or cæsura, separates the two halflines. • Each half-line has two strongly stressed syllables. • The first lift in the second half-line (i.e. the third stress) is always alliterated with either or both stressed syllables in the first half-line. • The second stress in the second half-line, i.e. the fourth stress does not alliterate. Anglo-Saxon Alliterative Versification cont. Thus there are the following variants: (‘A’ marks an alliterating syllable, ‘X’ marks a non-alliterating syllable) 1. 2. 3. A A || A X A X || A X X A || A X Beowulf Manuscript Beowulf is the conventional title of an Old English heroic epic poem consisting of 3182 alliterative long lines. Its composition by an anonymous Anglo-Saxon poet is dated between the 8th and the early 11th century. The poem appears in what is today called the Beowulf manuscript or Nowell Codex (British Library MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv), along with other works. Beowulf Manuscript Examples from Beowulf (translated by Michael Alexander 1. It is a sorrow in spirit A A || for me to say to any man A X 2. Then spoke Beowulf, son of Edgeheow A X || A X 3. A boat with a ringed neck rode in the haven X A || A X Further examples Alliterative stress within polisyllabic word It was not remarked then if a man looked X A || A X Vowel alliteration To encompass evil, an enemy from hell X A || A X The ample eaves adorned with gold A A || A X A twentieth century example - Ezra Pound: Canto I (A free translation of the opening of Odyssey 11) We set up mast and sail A A || Bore sheep aboard her, A A || Heavy with weeping, X A || Bore us out onward A X || Circe's this craft, A (?) A || on that swart ship, A X and our bodies also A X so winds from sternward A X with bellying canvas, A X the trim-coifed goddess. A X Ezra Pound (1885-1972) Significance of Sound Patterning Cohesive and mnemonic function Primordial and bardic poetry was transmitted orally, repetitive formal components bound words together and thus enhanced memorability. The metrical frame creates a musical body for the poem; it may also contribute to a level of sound symbolism, onomatopoeia, onomatopoeic words. Stress-Verse Native Metre / Folk Metre Sing a song of sixpence, A pocket full of rye; Four and twenty blackbirds Baked in a pie. When the pie was opened, They all began to sing. Now, wasn't that a dainty dish To set before the King? Sixpence cont. Sing a song of sixpence, / / A pocket full of rye; / / Four and twenty blackbirds / / Baked in a pie. / / Or: Sixpence cont. Sing a song of sixpence, / / / A pocket full of rye; / / (p) Four and twenty blackbirds / / / Baked in a pie. / / (p) (p) = pause Stress-Verse Ballad Metre Ballad metre is a form of poetry that alternates lines of four and three beats, often in quatrains, rhymed abab. The anonymous poem Sir Patrick Spens demonstrates this well. The alternating sequence of four and three stresses is called common measure when used for hymns. Sir Patrick Spens The king sits in Dumfermline town. / / / / Drinking the blude-red wine: / / / 'O whare will I get a skeely skipper, / / / / To sail this new ship of mine?' / / / Dunfermline Palace Ruin Dunfermline was Scotland’s capital in the 11th century Foot-Verse Syllable-Stress Verse / Accentual-Syllabic Metre After the Norman Conquest, from the 12th century on accentual-syllabic versification started to appear. It went hand in hand with strophic construction and rhyming line endings. Out of stressed and unstressed syllables metrical feet were created after the pattern of ancient Greek and Latin poetry. In accentual syllabic foot-verse both the number of stressed and unstressed syllables are fixed, and also their respective positions in the poetic line. Foot Verse Stressed / Accentual-Syllabic Metre Ancient Greek and Latin prosody is quantitative, i.e. the regular alternation of syllables is based on their duration. Quantitative versification makes distinction between long and short syllables. A syllable is long if the vowel sound in it is long or if it Is short but followed by more two or more consonants. A syllable is short if the vowel sound in it is short and Is followed by zero or one consonant sound. Accentual-Syllabic Metre / Quantitative Versification English accentual-syllabic foot-verse is sometimes called quantitative. It is, however, is inaccurate. But quantitative versification is based on the ‘quantity’, i.e. the duration of a syllable. Apart from a few technical experiments, duration of syllables is not a metre constitutive principle in English verse. Quantitative versification makes metrical feet using short and long syllables. Quantitative Versification Metrical Feet The foot is the basic metrical unit that generates a line of verse in quantitative versification. The foot is a purely metrical unit; there is no inherent relation to a word or phrase as a unit of meaning or syntax. A foot is composed of syllables, the number of which is limited. The feet are classified first by the number of syllables in the foot (disyllabic feet have two, trisyllabic three, And tetrasyllabic four syllables), and by the pattern of vowel lengths. Qualitative vs. quantitative metre (from the Wikipedia entry on ‘Prosody’) The meter of much poetry of the Western world and elsewhere is based on particular patterns of syllables of particular types. The familiar type of meter in English language poetry is called qualitative meter, with stressed syllables coming at regular intervals (e.g. in iambic pentameter, typically every even-numbered syllable). Many Romance languages use a scheme that is somewhat similar but where the position of only one particular stressed syllable (e.g. the last) needs to be fixed. The meter of the old Germanic poetry of languages such as Old Norse and Old English was radically different, but still was based on stress patterns. Qualitative vs. quantitative metre (from the Wikipedia entry on ‘Prosody’) Many classical languages, however, use a different scheme known as quantitative metre, where patterns are based on syllable weight rather than stress. In dactylic hexameter of Classical Latin and Classical Greek, for example, each of the six feet making up the line was either a dactyl (long-short-short) or spondee (long-long), where a long syllable was literally one that took longer to pronounce than a short syllable: specifically, a syllable consisting of a long vowel or diphthong or followed by two consonants. The stress pattern of the words made no difference to the meter. A number of other ancient languages also used quantitative meter, such as Sanskrit and Classical Arabic (but not Biblical Hebrew). Quantitative Versification Most common feet (symbols: ¯ = long syllable, ˘ = short syllable) iamb or iambic foot: ˘ ¯ trochee or trochaic foot: ¯ ˘ anapaest or anapaestic foot: ˘ ˘ ¯ dactyl of dactylic foot: ¯ ˘ ˘ spondee or spondaic foot: ¯ ¯ pyrrhic or pyrrhic foot: ˘ ˘ tribrach: ˘ ˘ ˘ molossus: ¯ ¯ ¯ minor ionic: ˘ ˘ ¯ ¯ choriamb: ¯ ˘˘ ¯ English Accentual-Syllabic Metre English prosody is based on the regular alternation of stressed and unstressed syllables. Consequently classical Greek and Latin quantitative metrical feet are translated into syllable stresses: 'long' becomes 'stressed' (or 'accented'), and 'short' becomes 'unstressed‘ (or 'unaccented'). English Accentual-Syllabic Metre For example, an iamb, which is short-long in classical meter, becomes unstressed-stressed, as in the English word “today”; a trochee is constituted of a stressed and unstressed syllable, as in “never”; a dactyl is constituted of a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed ones, as in “yesterday”; while an anapaest is constituted of two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed one, as in “interrupt”. A spondee is made of two successive stressed syllables, as in “heartbreak”; a pyrrhic is made of two successive unstressed syllables and the phrase “of the”. English metrical feet iamb or iambic foot: X / trochee or trochaic foot: / X anapaest or anapaestic foot: X X / dactyl of dactylic foot: / X X spondee or spondaic foot: / / pyrrhic or pyrrhic foot: X X tribrach: X X X molossus: / / / minor ionic: X X / / choriamb: / X X / English Accentual-Syllabic Metre For the scansion of an English poem the standard Symbols are used (the symbol ‘|’ marks foot boundary) Down by the salley gardens my love and I did meet X / | X / | X / | X ||X / | X / |X / Whose woods these are I think I know. X / | X / | X / |X / (Frost) (Yeats) English Accentual-Syllabic Metre Metrical feet add up to poetic lines, which consequently are defined in terms of the number and type of poetic feet they contain: Monometer: one foot Dimeter: two feet Trimeter: three feet Tetrameter: four feet Pentameter: five feet Hexameter: six feet English Accentual-Syllabic Metre Thus we can discern Iambic monometers (i.e. one-stress iambic lines) Thus I Pass by And die As one Unknown And gone (Robert Herrick: Upon His Departure Hence, 1648) English Accentual-Syllabic Metre Or anapaestic tetrameters (four-stress anapestic lines) There's little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head, X / X X / |X X / | X X / That curled like a lamb's back, was shaved: so I said, X / | X X / | X X / | XX / "Hush, Tom! never mind it, for when your head's bare, X / | X X /| X X / | X X / You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair. X / | X X / | X X /| X X / (William Blake: The Chimney Sweeper) English Accentual-Syllabic Metre Or iambic pentameters (five-stress iambic lines) There was a roaring in the wind all night; X / |X / |X / | X / | X / The rain came heavily and fell in floods; But now the sun is rising calm and bright; The birds are singing in the distant woods; Over his own sweet voice the Stock-dove broods; The Jay makes answer as the Magpie chatters; And all the air is filled with pleasant noise of waters. (from William Wordsworth: Resolution and Independence) William Wordsworth (1770-1850) (from the National Portrait Gallery) English Accentual-Syllabic Metre Iambic pentameter has a distinguished role in the history of English poetry. If unrhymed, it is called blank verse (e.g. Shakespeare’s plays) Now is the winter of our discontent Made glorious summer by this sun of York; And all the clouds that lour'd upon our house In the deep bosom of the ocean buried. (Shakespeare: Richard III) English Accentual-Syllabic Metre If pair-rhymed, it is called heroic couplet (e.g. Alexander Pope’s Essay on Criticism) Of all the Causes which conspire to blind Man's erring Judgment, and misguide the Mind, What the weak Head with strongest Byass rules, Is Pride, the never-failing Vice of Fools. (from Alexander Pope: Essay on Criticism) English Accentual-Syllabic Metre It is important to notice that the alternation of stressed and unstressed syllable in accentual-syllabic metre is not entirely rigid. In iambic forms, e.g. a poet may use substitute feet. The two syllabic spondee and pyrrhic are proper substitute feet for iambs. Sometimes poets add an extra unstressed syllable, thus substituting an anapest for an iamb. Substitution A sudden blow: the great wings beating still X /| X / | X / | / /|X / Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed X /| X /|X X /| X / | X / By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill, X X| / / | X / | / X| X / He holds her helpless breast upon his breast. How can those terrified vague fingers push The feathered glory from her loosening thighs? X / | X / |X X | X / |X X / And how can body, laid in that white rush, But feel the strange heart beating where it lies? Substitution cont. A shudder in the loins engenders there The broken wall, the burning roof and tower And Agamemnon dead. Being so caught up, So mastered by the brute blood of the air, Did she put on his knowledge with his power Before the indifferent beak could let her drop? (William Butler Yeats: Leda and the Swan) Leda and the Swan 16th century copy after lost painting by Michelangelo English Accentual-Syllabic Metre A metrical line has three rhythmic levels: Oh, to vex me, contraryes meet in one (Donne) (iambic pentameter) 1. Abstract metrical pattern X/|X/|X/|X/|X/ 2. Actual rhythm of the particular line XX|/X|/X|X/|X/ 3. Speech rhythm XX/X/XX\X\ (where ‘\’ marks secondary stress) Rough and Smooth Rhythms If the three levels fall apart, as in the above excerpt of Donne’s poem, the rhythm is ‘rough’. If they tend to coalesce, as in this line by Donne’s contemporary, Edmund Spenser, the rhythm is ‘smooth’: One day I wrote her name upon the strand (Edmund Spenser: Amoretti, Sonnet 75) Edmund Spenser (1552-1599) John Donne (1572-1631) Rhymes English accentual-syllabic poems may rhyme. Rhyme is the identity of sound between words. Rhyme is not necessarily based on identity of spelling. Pronunciation is the essence. great rhymes with mate whereas bough does not rhyme with though great and meat look alike, but pronounced differently, they are called eyes-rhymes Sound Parallelism Rhyme is only one aspect of sound-parallelism. Based on the concept of the linguistic formula of a syllable, i.e. a cluster of up to three consonants followed by a vowel nucleus followed by a cluster of up to four consonants (C⁰⁻³–V–C⁰⁻⁴), Geoffrey Leech set up the following chart of sound patterns: Sound Parallelism from Geoffrey N. Leech: A Linguistic Guide to English Poetry. London: Longman, 1969, 89 a CVC b CVC great/grow great/fail send/sit send/bell alliteration assonance c CVC great/meat send/hand consonance d CVC great/grazed send/sell e CVC great/groat send/sound pararhyme f CVC great/bait send/end reverse rhyme rhyme Rhyme Consonance is often called half-rhyme I have met them at close of day Coming with vivid faces From counter or desk among grey Eighteenth-century houses. (from W. B. Yeats: Easter 1916) Easter Rising, Dublin 1916 Internal Rhymes By rhymes generally terminal rhymes are meant. However, poets use internal rhymes within a line, usually followed by a break (caesura): And through the drifts the snowy clifts Did send a dismal sheen: Nor shapes of men nor beasts we ken – The ice was all between. (from S. T. Coleridge: The Rime of the Ancient Mariner) Poetic Forms The disposition of lines into groups falls into two categories: Stichic poetry, in which verse line follows verse line, as in Milton’s Paradise Lost. Stichic poetry is often segmented into verse paragraphs, i.e. passages of irregular length divided by a space-line. Strophic poetry, in which groups of lines (stanza) are formed, as in Keats’s Ode on a Grecian Urn. Rhyme Schemes and Poetic Forms Strophic or stanzaic forms are often bound together by rhymes. Stanza forms are determined by numbers of lines: Couplet – two-line stanza Tercet – three line stanza Quatrain – four-line stanza Stanza (Italian ‘station, stopping place’) A structural unit in verse composition, a sequence of lines arranged in a definite pattern of meter and rhyme scheme which is repeated throughout the whole work. Stanzas range from such simple patterns as the couplet or the quatrain to such complex stanza forms as the Spenserian or those used by Keats in his odes. (Alex Preminger, ed.: Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. Enlarged edition. London: Macmillan, 1975) Stanzas may consist of metrically identical or different lines. Rhyme Scheme Patterns of rhyme within larger units of poetry marked by letters : A or a: first line and every following line rhyming with it B or b: next new rhyme and every following line rhyming with it Rhyme Schemes Couplets Couplet: aa bb cc, etc. Had we but world enough, and time, This coyness, lady, were no crime. We would sit down and think which way To walk, and pass our long love's day. (from Andrew Marvell: To his Coy Mistress) Rhymes Schemes Alternate Rhymes Alternating / alternate / cross rhymes: abab cdcd, etc. The curfew tolls the knell of parting day, The lowing herd winds slowly o'er the lea, The ploughman homeward plods his weary way, And leaves the world to darkness and to me. (from Thomas Gray: Elegy Written in a Country Church-Yard) Rhyme Schemes Envelope Rhymes Envelope / enclosed: abba cddc, etc. The world is too much with us; late and soon, Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers: Little we see in nature that is ours; We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon! (William Wordsworth: The world is too much with us; late and soon) Rhyme Schemes Terza Rima Terca rima: aba bcb cdc, etc. (It is a type interlocking rhyme patterns: word unrhymed in 1st stanza is linked with words rhymed in 2nd stanza.) O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn's being, Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing, Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red, Pestilence-stricken multitudes: O thou, Who chariotest to their dark wintry bed Rhyme Schemes Terza Rima cont. The winged seeds, where they lie cold and low, Each like a corpse within its grave, until Thine azure sister of the Spring shall blow Her clarion o'er the dreaming earth, and fill (Driving sweet buds like flocks to feed in air) With living hues and odors plain and hill: (from P. B. Shelley: Ode to the West Wind) Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) by Alfred Clint (1807–1883) Rhyme Schemes Ottava Rima of Italian origin rhyme scheme: ABABABCC Three alternate rhymes plus a closing couplet consists of iambic lines, usually pentameters Byron’s Don Juan is a well known example Ottava Rima That is no country for old men. The young In one another's arms, birds in the trees - Those dying generations - at their song, The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas, Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long Whatever is begotten, born, and dies. Caught in that sensual music all neglect Monuments of unageing intellect. (from W. B. Yeats: Sailing to Byzantium) Rhymes Schemes Rhyme Royal rhyme scheme: ABABBCC usually iambic pentameter Geoffrey Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde is a well-know example Rhyme Royal Here at right of the entrance this bronze head, Human, superhuman, a bird's round eye, Everything else withered and mummy-dead. What great tomb-haunter sweeps the distant sky (Something may linger there though all else die;) And finds there nothing to make its tetror less Hysterica passio of its own emptiness? (from W. B. Yeats: A Bronze Head) Rhyme Schemes Spenserian Stanza Rhyme scheme: ABABBCBCC The Spenserian stanza was invented by Edmund Spenser and used it for his epic poem The Faerie Queene. Each stanza contains nine lines in total: eight lines in iambic pentameter followed by an iambic hexameter (alexandrine). Spenserian Stanza The wicked witch now seeing all this while The doubtfull ballaunce equally to sway, What not by right, she cast to win by guile, And by her hellish science raisd streightway A foggy mist, that overcast the day, And a dull blast, that breathing on her face, Dimmed her former beauties shining ray, And with foule ugly forme did her disgrace: Then was she faire alone, when none was faire in place. (from Edmund Spenser: Faerie Queene) Edmund Spenser The Faerie Queene The Sonnet Consists of fourteen lines divided into stanzas. Iambic pentameters (or iambic hexameters, also called alexandrines, sometimes iambic tetrameters). The rhyme schemes is fixed. There are three main types. The Petrarchan / Italian Sonnets John Donne: Holy Sonnet 19 Oh, to vex me, contraryes meet in one: Inconstancy unnaturally hath begott A constant habit; that when I would not I change in vowes, and in devotione. As humorous is my contritione As my prophane Love, and as soone forgott: As ridlingly distemper'd, cold and hott, As praying, as mute; as infinite, as none. I durst not view heaven yesterday; and to day In prayers, and flattering speaches I court God: To morrow I quake with true feare of his rod. So my devout fitts come and go away Like a fantistique Ague: save that here Those are my best dayes, when I shake with feare. A B B A A B B A C D D C E E According to the stanzaic pattern, you can print like thie (actually many sonnets are printed this way: Oh, to vex me, contraryes meet in one: Inconstancy unnaturally hath begott A constant habit; that when I would not I change in vowes, and in devotione. A B B A 1st quatrain As humorous is my contritione As my prophane Love, and as soone forgott: As ridlingly distemper'd, cold and hott, As praying, as mute; as infinite, as none. A B B A 2nd quatrain I durst not view heaven yesterday; and to day In prayers, and flattering speaches I court God: To morrow I quake with true feare of his rod. C D D 1st tercet So my devout fitts come and go away Like a fantistique Ague: save that here E Those are my best dayes, when I shake with feare. C 2nd tercet E The Petrarchan Sonnet 4+4+3+3=8+6 A B B A 1st quatrain A B B A octave 2nd quatrain turn C D C D C D 1st tercet sestet 2nd tercet The English Sonnet William Shakespeare: Sonnet 75 So are you to my thoughts as food to life, Or as sweet-seasoned showers are to the ground; And for the peace of you I hold such strife As 'twixt a miser and his wealth is found. Now proud as an enjoyer, and anon Doubting the filching age will steal his treasure, Now counting best to be with you alone, Then bettered that the world may see my pleasure, Sometime all full with feasting on your sight, And by and by clean starved for a look, Possessing or pursuing no delight Save what is had, or must from you be took. Thus do I pine and surfeit day by day, Or gluttoning on all, or all away. A B A B C D C D E F E F G G The English Sonnet 4 + 4 + 4 + 2 = 8 + 4 + 2 = 12 + 2 A B A B 1st quatrain C D C D 2nd quatrain turn E F E F 3rd quatrain G G closing couplet The Spenserian Sonnet Edmund Spenser: Amoretti 75 One day I wrote her name upon the strand, But came the waves and washed it away: Again I wrote it with a second hand, But came the tide, and made my pains his prey. Vain man, said she, that doest in vain assay A mortal thing so to immortalize, For I myself shall like to this decay, And eek my name be wiped out likewise. Not so (quoth I), let baser things devise To die in dust, but you shall live by fame: My verse your virtues rare shall eternize, And in the heavens write your glorious name. Where whenas Death shall all the world subdue, Out love shall live, and later life renew. A B A B B C B C C D C D E E The Sonnet Petrarchan / Italian Rhyme scheme abba|abba||cdc|dcd abba|cddc||efg|efg/eef|ggf quatrains - envelope rhymes repeated turn after line 8 (turn markers: but, though, yet, etc.) tercets quatrains versus tercets based on opposition, thesis – antithesis, static quality The Sonnet English / Shakespearean Rhyme scheme a b a b | c d c d || e f e f || g g alternate rhymes two turns: the first one after line 8 the second one after line 12 quatrains versus closing couplet (summary, conclusion) dramatic quality, tripartite structure: thesis – antithesis – synthesis The Sonnet Spenserian Rhyme scheme a b a b | b c b c || c d c d || e e A mixture of the two, the overlapping rhymes create a similar acoustic effect to that of the Italian sonnet, yet displays two turn, thus represents a more dramatic quality. However, the overlapping rhymes blur the tripartite division. Semi-strict forms, loosely metrical poems Poets often use loosely metrical patterns. It either means the employment of metrical substitutions or variations, as in S. T. Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner, with subtle irregularities in the ballad measure, e.g. With throats unslaked, with black lips baked, We could nor laugh nor wail; Through utter drought all dumb we stood! I bit my arm, I sucked the blood, And cried, A sail! a sail! Semi-strict forms, loosely metrical poems or the use of metrical lines of irregular length, as T. S. Eliot’s Preludes, Or it may take other, more radical forms of only hinting at the vague memory of strict metrical patterns. T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) Preludes I The winter evening settles down With smell of steaks in passageways. Six o'clock. The burnt-out ends of smoky days. And now a gusty shower wraps The grimy scraps Of withered leaves about your feet And newspapers from vacant lots; The showers beat On broken blinds and chimneypots, And at the corner of the street A lonely cab-horse steams and stamps. And then the lighting of the lamps. Preludes II The morning comes to consciousness II Of faint stale smells of beer From the sawdust-trampled street With all its muddy feet that press To early coffee-stands. With the other masquerades That times resumes, One thinks of all the hands That are raising dingy shades In a thousand furnished rooms. Preludes III You tossed a blanket from the bed You lay upon your back, and waited; You dozed, and watched the night revealing The thousand sordid images Of which your soul was constituted; They flickered against the ceiling. And when all the world came back And the light crept up between the shutters And you heard the sparrows in the gutters, You had such a vision of the street As the street hardly understands; Preludes III cont. Sitting along the bed's edge, where You curled the papers from your hair, Or clasped the yellow soles of feet In the palms of both soiled hands. Preludes IV His soul stretched tight across the skies That fade behind a city block, Or trampled by insistent feet At four and five and six o'clock; And short square fingers stuffing pipes, And evening newspapers, and eyes Assured of certain certainties, The conscience of a blackened street Impatient to assume the world. Preludes IV cont. I am moved by fancies that are curled Around these images, and cling: The notion of some infinitely gentle Infinitely suffering thing. Wipe your hand across your mouth, and laugh; The worlds revolve like ancient women Gathering fuel in vacant lots. Bibliography Attridge, Derek: Poetic Rhythm. An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995 Brooks, Cleanth and Warren, Robert Penn: Understanding Poetry. 4th edition. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976 Fry, Stephen: The Ode Less Travelled. Unlocking the Poet Within. London: Hutchinson, 2005 Hobsbaum, Philip: Metre, Rhythm and Verse Form. London: Routledge, 1996 Leech, Geoffrey N.: A Linguistic Guide to English Poetry. London: Longman, 1969 Scannel, Vernon: How to Enjoy Poetry. London: Piatkus, 1983 Preminger, Alex, ed.: Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. Enlarged edition. London: Macmillan, 1975