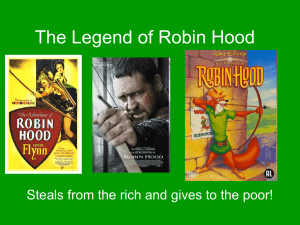

Robin Hood - WordPress.com

advertisement

Robin Hood: The Uses and Re-uses of the Popular Outlaw Hero ENG6552: The Continuing Middle Ages Thursday 5th March 2015 AS15 Structure - Historiography - The Medieval Robin Hood - Yeoman Hero - Robin Hood in the 16th Century - Gentrification? - Robin Hood in the Seventeenth Century - The Eighteenth Century - Brute, Buffoon, Hero - Rediscovery and Reconstruction - The Nineteenth Century - The Medieval Revival - Robin Hood of Hollywood Historiography James C. Holt, Robin Hood, 1982 Barrie Dobson & John Taylor, Rymes of Robyn Hood, 1976 Stephen Knight, Robin Hood: A Mythic Biography, 1994 Stephanie Barczewski, Myth and National Identity, 2004 Historiography on Outlaws and Highwaymen Social Bandit – someone whom the lord and state regard as criminal, but remain popular in peasant societies as champions, freedom fighters. Eric Hobsbawm, Bandits, 1969 Gillian Spraggs, Outlaws and Highwaymen, 2001 Participation Thesis - Between c.1500 and c.1700 there was no such thing as “high” culture and “popular” culture. All classes shared in the same entertainments. Withdrawal Thesis - Middle and upper classes begin to withdraw from participation in “popular” culture and an “elite” culture emerges. C.1650 – late 1700s Peter Burke, Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe, 1978 Rediscovery Thesis - Around late 18th century middle-classes “rediscovered” supposedly plebeian folk tales.. The Medieval Robin Hood I can noughte parfitly my pater noster as the prest it syngeth, but I can rymes of Robyn Hode and Randalf erle of Chestre – William Langland, Piers Plowman (c.1380). “Lithe and lysten gentylmen That be of frebore blode I shall ye tell of a good yeman His name was Robyn Hode.” “Yeoman” – debates re: definitions: - ‘independent and with a pride in themselves and their free status, who would brook interference from no man’ (Keen, 1987, p.147). - ‘an intermediary social category between husbandman and gentleman’ (Pollard, 2004, p.34). - ‘These men enjoyed lower social status than the knights, but they were by no means menial; they were fed and liveried and were often drawn from gentle families’ (Holt, 1989, p.117). Early Robin Hood Ballads - Robin Hood and the Monk (c.1450) - Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne (c.1470c.1506.) - Robin Hood and the Potter (c.1470). - Robin Hood and the Beggar (c.1450-1500). Victorian illustration of Robin Hood killing Guy of Gisborne. The Medieval Audience Rymes of Robin Hood originally orally recited (not sung). James C. Holt argues that a tale like the Geste was performed for the courtly classes, and notes its similarity to other long medieval Arthurian poems. Thomas Ohlgren argues that the ballads were originally composed for an urban audience, pointing to the ballads’ celebration of forest life being something town dwellers wouldn’t experience. Medieval ballad singers/minstrels (13th C.). Knight brings in the history of printing to the argument, saying that when tales such as the Geste began to be printed, they were aimed at an audience composed of those from a higher class of society, but notes that tales of Robin Hood were still enjoyed by lower classes through the oral tradition Function of Robin Hood Ballads Entertainment!!! Carnivalesque Entertainment? May Day Celebrations c.1600 Bakhtin, Mikhail (1941). Rabelais and his world. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. A “Bad” Robin Hood? The 16th and 17th Centuries Walter Bower, Scotichronicon, 15th Century “the famous murderer, Robin Hood, as well as Little John”. John Major, Historia majoris Britanniae, tam Angliae quam Scotiae, 1521 “About this time it was, as I conceive, that there flourished those most famous robbers Robert Hood, an Englishman, and Little John, who lay in wait in the woods, but spoiled of their goods those only that were wealthy.” Gentrification? Robert, Earl of Huntingdon “in an olde and auncient Pamphlet I finde this written of the sayd Robert Hood. This man (sayth he) discended of a nobel parentage: or rather beyng of a base stocke and linage, was for his manhoode and chivalry advaunced to the noble dignité of an Erle.” Richard Grafton, A Chronicle at Large and meere History of the affayres of Englande and Kinges of the Same, 1569 Gentrification (cont.) Martin Parker’s ballad entitled A True Tale of Robin Hood (1631). Anthony Munday, The Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntingdon & The Death of Robert, Earl of Huntingdon (c.1600). Late Seventeenth/Early Eighteenth Century: Hero, Brute, Buffoon “We may begin by positing three categories of thief: hero, brute, buffoon” – Lincoln B. Faller, Turned to Account: The Forms and Functions of Criminal Biography in Late Seventeenth- and Early Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge UP, 1987), p.127. Robin Hood the Brute This bold robber, Robin Hood, was, some write, descended of the noble family of Huntingdon; but that is only fiction, for his birth was but very obscure, his pedigree ab origine being no higher than poor shepherds.- Smith’s Highwaymen He was bred up a butcher, but being of a very licentious, wicked inclination, he followed not his trade, but in the reign of King Richard the First, associate[ed] himself with several robbers and outlaws. (Ibid). ‘Murder was viewed as ‘a direct attack on God, carrying with it “a sacrilegious guilt” that tainted the murderer’s society as well as himself and could threaten both with divine displeasure’- Lincoln B. Faller (1987). The Function of 18th-Century Criminal Biography Robin Hood the Buffoon Robin Hood the Hero Robin Hood: That Celebrated English Outlaw Robin Hood was born at Locksley, in the county of Nottingham, in the reign of King Henry the Second, and about the year of Christ 11 60. His extraction was noble…He is frequently styled, and commonly reputed to have been Earl of Huntingdon. In [the] forests, and with this company, he for many years reigned like an independent sovereign ; at perpetual war, indeed, with the King of England…with an exception, however, of the poor and needy. That our hero and his companions, while they lived in the woods, had recourse to robbery for their better support is neither to be concealed nor to be denied…But it is to be remembered … [that] he took away the goods of rich men only ; never killing any person … [never] took anything from the poor, but charitably fed them with the wealth he drew from the abbots. Gentrification? Ritson’s Legacy: The Nineteenth Century and the Medieval Revival Scott ‘first turned men’s minds towards the Middle Ages’ – Thomas Carlyle. The Nineteenth Century (cont.) The Nineteenth Century (cont.) Robin Hood of Hollywood You the freemen of this forest swear to despoil the rich only to give to the poor, to shelter the old and the helpless, to protect all women rich and poor, Norman or Saxon, and swear to fight for a free England, to protect her loyally until the return of our king and sovereign Richard the Lionheart, and swear to fight to the death against all oppression. The American Robin Hood Most of the twentieth-century Robin Hoods of television and film are in some way a gentleman…the implied consensus is that it is perfectly appropriate to have a man of noble [rich] birth leading a popular movement – and of course the leaders of the Democrats in America and the Labour Party in Britain would agree. (Knight, p.161). Conclusion Killer and gentleman, myth and everyday hero, village symbol and international liberal, joker and rebel, nature lover and fierce hunter, boyish charmer and father figure to children, man among men and helper to strong women – Robin Hood’s identity seems to undergo endless variations in verbal and visual texts. Stephen Knight, Robin Hood: A Mythic Biography (Ithaca: Cornell UP). P.204. Any Questions?