The White League - Social Circle City Schools

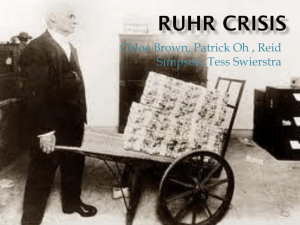

advertisement

The White League Origins of the White League After the Civil War, Louisiana drafted and implemented a new constitution that abolished slavery and significantly diminished the political clout of the "old guard" of planters and merchants. In many cases, Union army officers and other Northerners were appointed to government offices in the state. The White League, a paramilitary group comprised of former Confederate soldiers and jilted planters and merchants, was formed in 1874 in St. Landry Parish with the distinct political goals of intimidation of Republican candidates, voters, and officeholders, as well as free blacks, with the long-term aim of restoring white Southern Democratic rule. Unlike similar groups such as the Knights of the White Camellia and the Ku Klux Klan (both of these, which predate the White League, may have encouraged its formation by their success), the White League operated in the open and courted the sympathy of the Southern news media. Shortly after forming, they submitted their manifesto for publication in the Opleousas Courier, and the New Orleans Picayune eagerly reported of their exploits. The White League spread quickly from rural parishes to Louisiana's urban centers. The New Orleans chapter, known as the Crescent City White League, formed on July 1st of 1874. The Coushatta Massacre In August of 1874, an ongoing dispute between members of the White League and colleagues of Marshall Twitchell, a Vermont carpetbagger turned Louisiana state senator, culminated in violence in the town of Coushatta, the seat of Red River Parish. While Twitchell attended a Republican Convention in New Orleans, the White League moved in under the pretense of defending against an imaginary attack by armed black men. They rounded up Senator Twitchell's brother, two brothers-in-law, and three other white Republicans (all of whom he had appointed to parish offices), and demanded that they resign their positions of authority. Although the men agreed to resign, the White League took them as prisoners and executed all six while traveling from Coushatta to Shreveport, as well as approximately twenty freed black men who happened to be eyewitnesses. This successful raid, which bore significant resemblance to the Colfax Massacre perpetrated by the Knights of the White Camellia the previous year, simultaneously terrorized African-Americans and their sympathizers and empowered the White League to sharpen their political focus and attempt more daring work. The Battle of Liberty Place On September 14, 1874, seizing an opportunity provided when President Grant pulled most Federal troops out of Louisiana due to the yellow fever epidemic, the White League assembled in New Orleans. They demanded that Governor William Kellogg resign and be replaced with John McEnery, his unsuccessful Democratic opponent in the dubious 1872 gubernatorial election. The White League called a public meeting at the Henry Clay statue (then on Canal Street) and advanced through the French Quarter, bound for the Custom House, where Kellogg was headquartered at the time. The White League successfully routed the Metropolitan police with their superior numbers and there were at least 100 casualties. When the smoke cleared the next day, the White League controlled the police station and the arsenal. They installed Davidson Penn as Governor until McEnery, who was returning from Vicksburg, could arrive. Federal troops were already en route to New Orleans; President Grant had dispatched them as soon as he became aware of the White League's machinations in the city. U.S. General Emory met with Penn and McEnery and informed them that Kellogg would be restored by force if necessary, and with that the White League quietly and peacefully surrendered the city to the Federal troops. Although the White League had effectively overthrown Louisiana's state government for three days, no White League commander or member faced charges for the events of September 14th. In a long-winded published address just two weeks after the incident, Governor Kellogg attempted to prove his administration's solvency and appealed for "...a more just judgement and a more generous sympathy than have yet been given to the Republican state government of Louisiana." Nonetheless, white rule and black disenfranchisement would again become the norm just three years later with the Compromise of 1877, which formally ended Reconstruction and stifled integration efforts for many decades to come. Oscar Chopin's Involvement in the White League Oscar Chopin's business was that of a cotton factor. In the tough Reconstruction economy, where slave labor no longer existed and free labor consequently proved more expensive, Oscar's cotton business suffered considerably. Combine this with Oscar's probable regret at spending the Civil War years in France instead of fighting for the Confederacy, and his motivation to join the White League becomes clear. According to Toth, Oscar Chopin joined the First Louisiana Regiment, one of many groups associated with the White League. Oscar participated in the Battle of Liberty Place, on the side of the White League, and he remained loyal to the White League for many years. Kate Chopin's Opinion of the White League While Kate Chopin's specific thoughts on Oscar's political inclination are not known, it is evident from many of her stories that she laments the destructive effect of racial strife, especially in a region so wracked with miscegenation that race had ceased to be anything but arbitrary. Because of this, it is reasonable to speculate that she may have disapproved of the White League's cause and Oscar's association with it. Chopin articulates this idea most clearly in "Desiree's Baby." At the climax of a period of murmuring and vague discontent, Desiree observes a perfect picture of race's double-standard: "The baby, half naked, lay asleep upon her own great mahogany bed, that was like a sumptuous throne, with its satin-lined half-canopy. One of La Blanche's little quadroon boys - half naked too - stood fanning the child slowly with a fan of peacock feathers. Desiree's eyes had been fixed absently and sadly upon the baby, while she was striving to penetrate the threatening mist that she felt closing about her. She looked from her child to the boy who stood beside him, and back again; over and over. "Ah!" It was a cry that she could not help; which she was not conscious of having uttered. The blood turned like ice in her veins, and a clammy moisture gathered upon her face." In a side-by-side comparison, Desiree observes that her child and her slave's child are identical, and the reader can infer that the only real difference between the two is their family name and its trappings. Yet, once Armand realizes the implications of his child's skin color, it irrevocably eclipses his responsibility to his wife and child. For Chopin, who generally portrays motherhood favorably, this is a dire and undesirable circumstance indeed. Perhaps Kate Chopin had questions similar to Desiree's: "...look at our child. What does it mean?" In "Desiree's Baby," Chopin presented a concept of race as skin-deep in the purest sense of the word; if this literary sensibility informed her social sensibility, an assumption of her disdain at her husband's activity in the White League could not be far from the mark. Sources Toth, Emily. Kate Chopin's Private Papers. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998. Print. Landry, Stuart Omer. The Battle of Liberty Place: The Overthrow of Carpet-Bag Rule in New Orleans. New Orleans: Pelican Publishing Company, 1999. Print. Nystrom, Justin. New Orleans After the Civil War. Unpublished Manuscript: 2009. Print. "White League." Wikipedia. 23 Sep 2009. Web. 24 Sep 2009. . "Reconstruction: A State Divided." Cabildo. Louisiana State Museum, Web. 24 Sep 2009. .