7 - Harvard Master Plan

advertisement

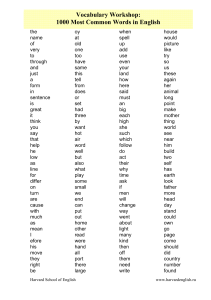

7. OPEN SPACE & NATURAL RESOURCES A. INTRODUCTION Harvard maintains a small-town feel despite its location so close to major highways and commuter rail service. The enduring sense of Harvard as a small New England town stems in part from the concentration of non-residential uses in just two areas and in part from the preservation of large amounts of land. This allows residents and visitors to enjoy the many natural resources within Harvard’s boundaries. With the Nashua River along the western boundary and the adjacent Oxbow Summer recreation at Bare Hill Pond. (Photo by Joseph Hutchinson) National Wildlife Refuge, Bowers Brook flowing northward through the center of the town from Bare Hill Pond, and the Oak Hill ridgeline along the eastern boundary, the town is blessed with irreplaceable natural landscapes. While many of these natural amenities are protected today, Harvard still has considerable land available for development – including scenic and ecologically significant landscapes. Open space, natural resources, and cultural landscapes are almost inseparable in a master plan even though they serve different functions and have different management needs. For this master plan as with its predecessors, Harvard places great weight on preserving and protecting land and water resources for environmental, scenic, agricultural, historical and recreational purposes. Harvard has been one of the state’s land conservation leaders for several decades, as evidenced by the large tracts of protected open and forested land found throughout the town. However, the Phase 1 master plan report underscores that conservation is more complicated than simply acquiring land, and Harvard residents know that more needs to be done. Stewardship, public education, and agricultural incentives will be needed to guide Harvard through its next era of growth and change. In addition, Harvard’s decentralized small-town government can be both an asset and a liability when it comes to planning and resource protection. On one hand, it helps to have many volunteers with shared interests working toward shared goals. On the other hand, coordinating multiple groups is difficult even under the best of circumstances. Harvard’s resource protection needs may be more easily and effectively addressed with some consolidation of existing boards and committees. Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT B. KEY FINDINGS Harvard has approximately 4,300 acres of protected open space, or roughly one-fourth of the Town’s total area. AT COREofOF HARVARD’S NATURAL BEAUTY At THE the core Harvard’s natural beauty is, of IS, OF COURSE, ITS LAND. course, its land. -Harvard Conservation Trust -Harvard Conservation Trust Much of the town is built on soils that are not very conducive to development. As technology continues to improve, areas that once seemed unbuildable may be easier and less costly to develop. Harvard still has plenty of room to grow, and not many physical impediments to new construction. Harvard has eight state-certified vernal pools and many more potential, undocumented vernal pools exist throughout the town. Over 2,000 acres of land in Harvard have direct bearing on the quantity and quality of public drinking water supplies in Harvard, Devens, and adjacent towns. Harvard has over 5,700 acres of land in environmentally sensitive locations: Areas of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC), and the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program’s (NHESP) BioMap 2 Core and Critical Habitat and Priority Habitats of Rare Species. Approximately 7,000 acres in Harvard are composed of prime farmland soils or soils of statewide or unique importance. Harvard has about 1,471 acres that are not currently developed and not protected from development, do not have environmental constraints, and are potentially developable based on size and access. Despite Harvard’s impressive efforts to protect land, water resources and wildlife habitats within its borders, the town is not immune to the effects of development which are felt throughout the north-central region of Massachusetts. Local concerns about traffic, watershed protection, stormwater, habitat disturbance, and environmental hazards will remain challenging to address without concerted regional action and regional cooperation. Although many neighboring towns share Harvard’s commitment to environmental quality, problems with growth management and the need for tax revenue make it difficult for communities to work toward a consistent vision. Like other small towns, Harvard has many elected and appointed town officials. Today (2014), there are six boards and committees working on various aspects of land and water resource protection: the Planning Board, Conservation Commission, Bare Hill Pond Watershed Management Committee, Community Preservation Committee, Agricultural Advisory Committee, and the Land Stewardship Committee (subcommittee of the 2 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT Conservation Commission), as well as the non-profit Harvard Conservation Trust. At times it has been difficult for Harvard to coordinate the roles and responsibilities of all of these groups. Jurisdiction is not always clear, too. C. EXISTING CONDITIONS Half a century of active pursuit of land preservation in Harvard has resulted in 4,244.9 acres of land in some form of permanent protection from development1, or one quarter of the area of Harvard. As shown in Map NR-1, these areas are widespread across the town and largely disconnected. The preserved lands include: 2,246.72 acres owned by the Town, including the water area of Bare Hill Pond but not including parcels with buildings on them (e.g. Town Hall, schools); 803.43 acres owned by US Fish & Wildlife Service; 368.28 acres owned by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts; 205.76 acres owned by the Harvard Conservation Trust; 236.68 acres owned by various entities with agricultural preservation restrictions; and 384.03 acres owned by various entities, with conservation restrictions. Harvard’s natural resources provide much of the cherished scenic and rural character enjoyed by residents and visitors alike. They also present challenges to the growth necessary for Harvard to continue to thrive economically. This starts with the fact that Harvard depends on on-site wastewater treatment facilities - septic systems – as well as individual water supply wells. Given the low density and widespread area of the majority of development in Harvard, establishing a public wastewater treatment system or a public water supply system is not a financially feasible option outside concentrated built-up areas, such as the Town Center.. As a guide for near-term planning and policies that affect development, the Master Plan assumes that Harvard will not expand its public infrastructure in the near future. 1. Water Resources Water resources in Harvard include both ground and surface water. For potable water, the primary areas of concern are the high and medium yield aquifers – areas with potentially adequate capacity for a public water supply – and the areas surrounding and recharging public water systems. The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) defines a public drinking water system this way: “a system for the provision to the public of water for human consumption, through pipes or other constructed conveyances, if such system has at least fifteen service connections or regularly serves an average of at least twenty-five 1 Source: GIS analysis by RKG Associates using Assessor data and 2008 Conservation Lands data from MRPC. 3 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT individuals daily at least sixty days of the year.”2 MassDEP further regulates land around public water supplies where activity could have an impact on drinking water quality and quantity. These areas are known as Zone II and Interim Wellhead Protection AreasArea (IWPA). The key difference between them is that the boundaries of a Zone II are determined from field tests while the IWPA is based on a regulatory formula that considersconsider the type of well and its design pumping rate. Zone II: "That area of an aquifer that contributes water to a well under the most severe pumping and recharge conditions that can be realistically anticipated (180 days of pumping at approved yield, with no recharge from precipitation). It is bounded by the groundwater divides that result from pumping the well and by the contact of the aquifer with less permeable materials such as till or bedrock. In some cases, streams or lakes may act as recharge boundaries. In all cases, Zone II shall extend up gradient to its point of intersection with prevailing hydrogeologic boundaries (a groundwater flow divide, a contact with till or bedrock, or a recharge boundary)3." IWPA: When a Zone II has not been approved by MassDEP for a public water supply system, an Interim Wellhead Protection Area (IWPA) is designated. These are circular areas designated by MassDEP through calculations based on the pumping rate of the well and its classification. The minimum area is a radius of 400 feet from the well, and for wells pumping 100,000 gallons per day or more, the largest default area is a one-half mile radius from the well. Land uses and development within Zone IIs and IWPAs are intended to be limited to protect the quality and quantity of water recharging the well, although it is the responsibility of each municipality to ensure that appropriate protections are in place through zoning regulations. Harvard’s Zoning Bylaw should be evaluated and updated to ensure consistency with state regulations to protect important water supplies. Map NR-2 shows the aquifer, Zone II, and IWPA areas in Harvard: Most of the 1,497 acres of mapped aquifers lie within Devens (959 acres), the Oxbow National Wildlife Refuge (187 acres), and the Delaney Wildlife Management Area (196 acres). Two Zone II areas extend into Harvard from abutting towns. Of the 1,395 acre Littleton Water Department Zone II, 51 acres abuts the Harvard/Boxborough town line, and 554 acres of the 987-acre Ayer Water Department Zone II extends into Harvard east of the rail line and west of Routes 110/111. 2 310 CMR 22.02 3 Ibid. 4 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT All of the 503-acre Devens/Mass Development Zone II is within the Harvard portion of Devens. . SeventySeventy-eight acres of the 760-acre Devens/Mass Development Zone II contributes to a well located in Ayer. There are 39 public water supply wells with designated IWPAs within Harvard, and the IWPA’s of 6 wells outside Harvard extend across town boundaries into the town. In total, Harvard has 1,007 acres4 of land within IWPAs. Finally, there are thirty-nine public water supply wells with designated IWPAs within Harvard, and portions of six more extend across town boundaries into Harvard. Despite the prevalence of land contributing rainfall to public water supplies, Harvard does not have any land use controls to help safeguard such supplies from contamination. SURFACE WATERS Surface waters in Harvard include rivers, streams, ponds, and wetlands. Precipitation falling on the ground either infiltrates the ground and enters the groundwater system, sometimes discharging to surface water or flows on the surface to a surface water. The demarcation of which surface water resource this runoff enters is the watershed, and each bit of land is within several watersheds from the Eastern Divide, New England Basin, and one of the three major basin watersheds in Massachusetts: the Nashua, the Merrimack, or the Sudbury/Assabet/Concord. There are ten sub-basins in Harvard within these three major basins, and for any particular pond or wetland, one could identify a smaller watershed area that only feeds that particular surface water resource. Map NR-3 shows the boundaries of the major basins and sub-basins within Harvard, along with the rivers, streams, ponds, and major wetlands. It should be noted that not all wetlands appear on this map, and for those that do, the boundaries are approximate. Bare Hill Pond is the largest and most prominent body of water in Harvard. The 103-acre main pond in the Delaney Wildlife Management Area in Harvard and Stow was created for flood control purposes, and is the second largest water body in Harvard. 6 Three smaller ponds lie within Devens: Mirror Lake, Little Mirror Lake, and Robbins Pond. There are half a dozen or so smaller ponds around town, most of which are part of larger wetland systems. 2. ACEC There are a total of 5,726 acres of land in Harvard that are within environmentally sensitive areas (see Map NR-4). These include Areas of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC), Core and Critical Habitat from the BioMap2, and Priority Habitats of Rare Species. As can be seen on the map, most of these areas overlap and amounts to 5,726 acres. Over half (3,300 acres) of these areas are along the Nashua River and in the Oxbow National Wildlife Refuge, extending up into N.B. Overlapping IWPA’s were not double counted. Harvard Conservation Trust, Trail map of Delaney WMA, http://harvardconservationtrust.org/trails.htm (accessed August 2014) 4 6 5 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT Devens and incorporating the Mirror Lakes and Robbins Pond (1,126 acres lie within the Devens boundary). A second significant environmentally sensitive area includes 1,488 acres on the eastern side of town, extending from Black Pond to Horse Meadow Pond. ACECs have been designated by the Massachusetts Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA) as places that receive special recognition because of the quality, uniqueness, and significance of their natural and cultural resources.7 They are identified and nominated at the community level and reviewed by EEA staff. ACEC designation creates a framework for local and regional stewardship of critical resource areas and ecosystems. ACEC designation also requires stricter environmental review of certain kinds of proposed development under state jurisdiction within the ACEC boundaries. There are 2,109 acres so designated in Harvard, including the Nashua River, the Oxbow, and environs. 3. Wildlife Habitat The Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP) and The Nature Conservancy’s (TNC) Massachusetts Program developed BioMap2 inBioMap2in 2010 as a conservation plan to protect the state’s biodiversity.8 BioMap2 is designed to guide strategic biodiversity conservation over the next decade by focusing land protection and stewardship on the areas that are most critical for ensuring the long-term persistence of rare and other native species and their habitats, exemplary natural communities, and a diversity of ecosystems. Those areas identified as Core Habitat, encompassing 4,882 acres in Harvard, are necessary to promote the long-term survival of Species of Special? Concern (those listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act as well as additional species identified in the State Wildlife Action Plan), exemplary natural communities, and intact ecosystems. The Critical Natural Landscape category was created to identify and prioritize intact landscapes that are better able to support ecological processes and disturbance regimes, and a wide range of species and habitats over long time frames. Landscape Blocks, the primary component of Critical Natural Landscapes, are large areas of intact predominately natural vegetation, consisting of contiguous forests, wetlands, rivers, lakes, and ponds. Pastures and power-line rights-of-way, which are less intensively altered than most developed areas, were also included since they provide habitat and connectivity for many species. There are 2,843 acres of such landscapes in Harvard. In producing BioMap2, the NHESP and TNC used specific data and sophisticated mapping and analysis tools to spatially define each of these components, calling on the latest research and understanding of species biology, conservation biology, and landscape ecology. Priority Habitats of Rare Species represent the geographic extent of habitat of state-listed rare species in Massachusetts based on observations documented within the last 25 years in the MassGIS website, http://www.mass.gov/anf/research-and-tech/it-serv-and-support/application-serv/office-ofgeographic-information-massgis/datalayers/acecs.html (downloaded 8/2014); Harvard statistics by RKG Associates Inc. 8/24/2014 8 MassGIS website, http://www.mass.gov/anf/research-and-tech/it-serv-and-support/application-serv/office-ofgeographic-information-massgis/datalayers/biomap2.html (downloaded 8/2014); Harvard statistics by RKG Associates Inc. 8/24/2014 7 6 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT NHESP database.9 They were digitized by NHESP scientists from documented observations of state-listed rare species and are based on such factors as reported species movements and known habitat requirements. Priority Habitat polygons are the filing trigger for determining whether or not a proposed project or activity must be reviewed by the NHESP for compliance with the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and its implementing regulations. The 3,972 acres in Harvard delineated as Priority Habitats can include wetlands, uplands, and marine habitats. The Priority Habitats presented here are those published in the Massachusetts Natural Heritage Atlas, 13th ed. (October 2008). Together, the areas shown on Map NR-4 represent the land areas that should be among the highest priority for protection, in order to maintain species diversity and a resilient ecology. Map NR-5 shows the same information along with the areas already protected (information from Map NR-1). Of the 4,245 acres of protected land in Harvard, 1,852 acres fall within one or more of the environmentally sensitive areas shown on this map. The state and federal governments own 1,080 acres. The Town owns 427 acres, including small portions of the water area of Bare Hill Pond. Land protected through APR’s and CR’s that are within environmentally sensitive areas total 188 acres. Finally, the Harvard Conservation Trust owns 87 acres within these areas. 4. Floodplain As one might expect, there is a high degree of correlation between the environmentally sensitive areas and areas prone to flooding. Map -6NR-55 shows the flood zones in Harvard. These areas are delineated by the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) and are the basis for floodplain management and mitigation. There are four categories of flood prone areas: the floodway, two categories where there is a one percent chance of flooding in any given year, and the area adjacent to that where there is a lower chance of flooding. The floodway is the zone where the majority of water flows during a flood event, including the river or stream channel and the lowest lying areas along the banks. No development should occur within this area. The two categories where there is a 1 percent annual chance of flooding (formerly known as the “100 year” floodplain) are differentiated by the presence or absence of base flood elevation data. Those areas with such data can be delineated more precisely. The fourth category, formerly known as the “500 year” floodplain, has a 0.2 percent chance of flooding in any given year. As expected, the majority of the flood prone areas in Harvard lie along the Nashua River and associated wetlands systems, Bower’s Brook including Bare Hill Pond, Cold Spring Brook, Bennetts Brook, and Elizabeth Brook into the flood control ponds in the Delaney Wildlife Management Area. In all, there are 2,796 acres of flood prone areas in Harvard: 784 acres within the floodway, 1,249 acres of areas with a one percent annual chance of flooding (including 613 acres in ponds), and 763 acres of areas with a 0.2 percent annual chance of flooding. Harvard’s MassGIS website, http://www.mass.gov/anf/research-and-tech/it-serv-and-support/application-serv/office-ofgeographic-information-massgis/datalayers/prihab.html (downloaded 8/2014); Harvard statistics by RKG Associates Inc. 8/24/2014 9 7 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT Protective Bylaw includes appropriate provisions to minimize adverse impacts due to flooding. . 5. Soils Thethe soils in Harvard have not changed since the first soil survey was completed in 1969. What has changed is the amount of information available about the suitability of the soils for various uses and the ability of people to deal with the limitations of the soils. The Natural Resources Conservation Service10 (NRCS) has published soil ratings for a number of uses, including for septic systems and dwellings. Rating terms indicate the extent to which the soils are limited by all of the soil features that affect the specified use. "Not limited" indicates that the soil has features that are very favorable for the specified use. Good performance and very low maintenance can be expected. "Somewhat limited" indicates that the soil has features that are moderately favorable for the specified use. The limitations can be overcome or minimized by special planning, design, or installation. Fair performance and moderate maintenance can be expected. "Very limited" indicates that the soil has one or more features that are unfavorable for the specified use. The limitations generally cannot be overcome without major soil reclamation, special design, or expensive installation procedures. Poor performance and high maintenance can be expected.11 The entire town -- in fact, the entire region—is rated by the NRCS as unsuitable for septic system absorption fields (leach fields). As a practical matter, this means septic systems in this area are more costly to design and build than in areas with soils rated suitable for septic system absorption fields. Soil scientists and other experts have designed new technologies to help overcome some of the limitations in the soils, enabling development of this area without as great a risk of pollution to the groundwater or surface water resources. As Map NR-6 shows, nearly the entire town is comprised of soils which are rated “very limited” for construction of dwellings with basements (single-family homes of three stories or less). Not surprisingly, most of the areas rated “not limited” or “somewhat limited” have already been developed; roughly 160 acres of such soils outside of Devens remain available for development, although much of it does not have direct access to existing roads. These soil suitability ratings for dwellings are based on the soil properties that affect the capacity of the soil to support a load without movement and on the properties that affect excavation and construction costs. The properties that affect the load-supporting capacity include depth to a water table, ponding, flooding, subsidence, linear extensibility (shrink-swell potential), and compressibility. The properties that affect the ease and amount of excavation include depth to a water table, ponding, flooding, slope, depth to bedrock or a cemented pan, hardness of bedrock or a cemented pan, and the amount and size of rock fragments. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), formerly known as the Soil Conservation Service (SCS). http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/ (accessed 8/2014) 11 USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service website, http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/soils/survey/ and associated pages (downloaded 8/2014). 10 8 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT As has been stressed in previous plans for Harvard, these limitations can be overcome through engineering and construction practices which, while more expensive than standard practices, should not be viewed as a physical impediment to development of various types within the town. The preservation of farmland soils is important.. Once developed, they are no longer available for agriculture except on a small household garden scale. These soils are shown on Map NR-7 and encompass 7,003 acres of land in Harvard. Farmland soils are classified as Prime, of Statewide Importance, or of Unique Importance12. Prime Farmland has the best combination of physical and chemical characteristics for economically producing sustained high yields of food, feed, forage, fiber, and oilseed crops, when treated and managed according to acceptable farming methods. Harvard has 2,372 acres of prime farmland. Farmland of Statewide Importance is vital for the production of food, feed, fiber, forage, and oil seed crops, as determined by the appropriate state agency or agencies. Generally, these include lands that are nearly prime farmland and that economically produce high yields of crops when treated and managed according to acceptable farming methods. Harvard has 3,124 acres of farmlands of statewide importance. Farmland of Unique Importance is land that might be used for the production of specific high value food and fiber crops. Examples of such crops are tree nuts, cranberries, fruit, and vegetables. In Massachusetts, Unique soils are confined to mucks, peats, and coarse sands. Cranberries are the primary commercial crop grown on these soils. The presence of other crops on these soils is usually – possibly always – limited to small, incidental areas. There are 1,146 acres of such soils in Harvard. 6. Development Suitability By combining the data layers from the previous maps, one can begin to get a sense of the development potential in Harvard today. Map NR-8 shows areas that are not suited to development and those that are better suited to development. Included in the areas not suited are wetlands, interim wellhead protection areas, zone II wellhead protection areas, floodways, one percent annual chance flood prone areas, BioMap2 core habitats, BioMap2 critical natural landscapes, areas of critical environmental concern, prime farmland soils, and farmlands of statewide or unique importance. Another way to look at land availability is to examine the parcels in town that are already developed or protected from development. Map NR-9 shows this analysis. The map also shows parcels in the Chapter 61 , 61A and 61B tax relief programsprogram as of 2008, which may or MassGIS website, ; http://www.mass.gov/anf/research-and-tech/it-serv-and-support/application-serv/office-ofgeographic-information-massgis/datalayers/soi.html (downloaded 8/2014) 12 9 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT may not have buildings on them – houses, barns, etc. The Chapter 61 lands are all subject to development or additional development (through subdivision) and should not be considered protected. It should be noted that in this analysis, any parcel with a single family home on it, regardless of whether the parcel is one acre or a hundred, is shown as developed. Clearly, some of these parcels could be further developed either through the subdivision process to add housing units to the current parcel, or through redevelopment with demolition of the existing house and new development. The next map in this series (Map NR-10) shows the land areas in Harvard that are vulnerable to development – they are neither developed nor protected from development. A significant amount of this land lies within areas identified in the 2002 Master Plan13 as important to preserve for their value as agricultural or historic landscape resources or where protection of groundwater resources or the Bare Hill Pond watershed is important. Map NR-10 shows a total of 1,471 acres that are not currently developed, are not protected from development, do not have environmental constraints, and are potentially developable based on size and access. The majority (sixty eight percent, or 1,008 acres) of these areas are in the Chapter 61 tax programsprogram, which indicates some level of desire by the owner to keep the land in agriculture, recreation, or forestry uses for a while. Without permanent protection, the land remains vulnerable to development. Based on the absence of wetland and floodplain areas, some of this land should be the focus of efforts to increase development density could occur, as a means to increase housing diversity in town as well as to reduce pressure on other land areas which are not as suitable for development. Table NR-1 shows the acreage of specific areas previously discussed, their percentage of the town, and percentage of the vulnerable lands. Table NR-1: Vulnerable Land Statistics Total Percent of Percent of Map Acreage Town* Vulnerable Lands Aquifer Areas 3 0.02% 0.16% NR-2 Zone II Wellhead 100 0.62 5.80 NR-2 Protection Areas Interim Wellhead 42 0.26 2.43 NR-2 Protection Areas Environmentally Sensitive 287 1.78 19.51 NR-4 Areas** Farmland Soils 859 5.32 58.40 NR-7 Notes: * 16,144 acres, does not include water or rights-of-way ** Includes Areas of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC), BioMap2 Core Habitat, BioMap2 Critical Natural Landscape, and NHESP Priority Habitats of Rare Species. Note that the data in this table are not additive, many of these areas overlap each other. Source: Analysis of GIS data by RKG Associates, August 2014 13 Community Opportunities Group et. al, Harvard Massachusetts Master Plan, (November 2002), Map 4-A. 10 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT Given that it is unrealistic for the Town or conservation organizations to preserve all – or even most of – the “vulnerable areas”10, and the fact that previous plans have recommended that preservation efforts should continue in areas designated as scenic, Map NR-11 shows the areas of Harvard that are vulnerable to development and the areas already protected, along with the 1982 designated scenic landscapes, which cover 41 percent of the town. Harvard is among a small handful of municipalities across the state with such a large percentage of the community so designated. The vulnerable lands that are adjacent to protected lands and are within a distinctive scenic landscape would be a reasonable “top priority” for protection, followed by those vulnerable lands adjacent to protected lands within noteworthy scenic landscapes or those that would bridge gaps in otherwise protected corridors. There are ninety-one land areas with a total of 868 acres that fall within one of these scenic landscape designations. Harvard should prioritize areas for protection efforts and identify specific parcels for acquisition of the land or conservation restrictions. Bare Hill Pond, arguably Harvard’s most significant natural resource, has had a history typical for ponds in Massachusetts which became prime real estate first for summer camps and later for year-round residences. Map NR-13 shows an aerial image of the area taken in April 2013. This image shows that much of the shoreline remains wooded although a majority of it appears to have been developed. Map NR-14 shows the land uses for the parcels within 1,000 feet of the shoreline, along with the IWPA zones in this area. Out of the 183 parcels, 113 are residential, five are developed with public or institutional uses, and fifty-nine are undeveloped. Of the undeveloped parcels, the Town of Harvard owns twenty-one parcels encompassing 280 acres, the Girl Scouts of Central and Western Massachusetts owns five parcels with 36 acres, the Harvard Conservation Trust owns three parcels totaling 22 acres, the Harvard Conservation Trust owns one parcel of 15.5 acres, and the state owns one 1.5 acre parcel. The development of the area around Bare Hill Pond began in 1887 with the construction of a camp on Sheep’s Island, followed a few years later by four more. Turner’s Lane was built in the 1910’s, Wilroy Avenue and Clinton Shores were developed in the 1930’s, Willard Shores was developed in the 1950’s, as were Peninsula Road and a number of homes along Warren Avenue. 15 More recent development has primarily been along the eastern and southern shores of the pond. The rate of development accelerated from 1.1 units per year prior to 1931 to 1.7 units per year between 1931 and 1960. From 1961 to 1990, growth slowed to 1.3 units per year, and since 1991 the rate of development has further slowed, to 0.8 units per year. 15 Development based on Assessor data, analyzed by RKG Associates, September 2014. 11 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT As the shoreline developed, problems started to show up in the pond. Numerous studies have been conducted on the water quality of the pond16. The first dam was constructed in the early 1800’s and rebuilt to increase the level of the pond in 183717. With the construction of nearly 100 camps or homes by the mid 1950’s, it’s not surprising that weed problems had become acute by that time. The first of three committees was formed to address the problems in 195918. Through the early 1960’s, spot treatments were done on the pond using herbicides and a weed cutter. In 1965 the Bare Hill Pond Committee ceased to exist, and no weed removal activities took place until 1972 when the Bare Hill Pond Study Committee was formed as a subcommittee of the Conservation Commission. Chemical treatment for weed control was conducted sporadically until 1983 when the Annual Town Meeting voted to approve a moratorium on the use of herbicides. After that, weed control has been done mainly through weed harvesting and drawdowns. In 1987 the Bare Hill Pond Watershed Management Committee was formed. This committee reports directly to the Board of Selectmen, and as the name suggests, has a broader focus than previous committees – it considers consider activities within the watershed, not just the pond itself. Until a new pumping system was installed in 2006, drawdowns (by lowering of the water through removal of dam boards) were limited to 3.5 feet19, which proved insufficient to limit the weeds adequately. Since the deep drawdown system began with( the capacity to achieve up to 8 feet of drawdown20) became operational, this method of weed control has been much more successful. In 2010, after extensive study and design, a stormwater management system was constructed to better handle the stormwater runoff entering the pond from the Town Center, the school and library parking lots, and Pond Road. As a result of this and the annual deep drawdowns that have taken place, the phosphorus levels which had landed the pond on the states endangered lakes list in the 1990’s have fallen dramatically21. Today the pond has a more natural balance, but watershed management should continue.. As can be seen in Map NR-14, there are numerous undeveloped parcels within one thousand feet of the shoreline of Bare Hill Pond. Of these, twenty could be developed. The Town owns the most significant portion of the undeveloped land, with twenty one parcels. If the Town’s intention is to preserve these lands in perpetuity, and it has not already been done, then the Town Meeting should vote such restrictions into place either through conservation restrictions or other deed restrictions. In addition to continuing with drawdowns and the maintenance of BHPWMC, http://www.harvard.ma.us/Pages/HarvardMA_BComm/BareHill/index, August 2014. H.G. Marsh, Bare Hill Pond Chronology of Activities, September 15, 2002. 18 Ibid. 19 BHPWMC, Deep Drawdown Pumping Project FAQ, 2004, http://www.harvard.ma.us/Pages/HarvardMA_BComm/BareHill/Deep %20Drawdown%20Project 16 17 20 Ibid. BHPWMC annual report, Harvard Annual Report for the Year 2013, http://www.harvard.ma.us/Pages/HarvardMA_BComm/ BOS/town, downloaded August 2014. 21 12 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT the stormwater system at the Pond Road area, public education directed at the property owners within the pond’s watershed should maintain the phosphorus levels and other pollutants close to today’s levels, even with a potential of additional housing development in the area. The owners of developments on the western shore of the pond should be encouraged to examine the stormwater runoff on their properties, with an eye toward constructing systems similar to the Pond Road system in the event that existing conditions continually contribute to problems within the pond. D. ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES OPEN SPACE AT DEVENS The portion of Harvard that lies within the boundaries of Devens totals 2,515 acres. Of that, 863 acres are either protected as open space or currently used for recreational purposes. Another 242 acres are proposed to be protected open space, which would bring the total amount of open space within Harvard’s portion of Devens to 1,105 acres. Map NR-15 shows the land uses of the open space parcels within Devens. An aerial view of the portions of Devens that lie within Harvard can be seen in Map NR-16. Map NR-17 shows protected lands and groundwater resources. Not surprisingly, the majority of the protected lands coincide with the Zone II and the aquifer areas in the Mirror Lake region. The mostly unprotected Zone II extending into Ayer around Grove Pond feeds the Ayer public water supply. Map NR-18 shows the protected lands in Devens along with the environmentally sensitive areas. Again, there is a high degree of correlation between these areas. There is one parcel that is planned for future development that lies mostly within the Devens Zone II, the medium yield aquifer, NHESP Priority Habitats of Rare Species, and BioMap2 Core Habitat: the former Salerno Circle residential neighborhood. Much of the housing in this neighborhood has been demolished, but much still remains today, boarded up and abandoned due to high concentrations of pesticides in the soil underlying the neighborhood. According to the Devens Reuse Plan, Salerno Circle is one of two designated “Special Use” areas. Future plans for this 87acre parcel include office, conference, and health care uses. Site design for any development will have to comply with existing viewshed restrictions for Fruitlands Museum and Prospect Hill. Given the presence of the groundwater feeding the water supply and the habitat areas, it may be prudent for this area to be cleaned up and developed in a manner consistent with protection of these resources. A smaller parcel just north of the Red Tail golf course has similar circumstances. The 18-acre former Davao neighborhood was completely demolished in 2005 and the pesticides in the soil remediated. The site is now ready for reuse. The 2006 Devens Reuse Plan called for a mixed residential neighborhood on this site, which would have been more compatible with the environmental constraints that exist than a more intense use would be. However, the three towns did not approve the 2006 Plan. Other protected lands within Harvard’s town boundary and within Devens include portions of the Oxbow National Wildlife Refuge north of Route 2 and extending along the Nashua River 13 Harvard Master Plan / Working Papers Series: Open Space & Natural Resources DRAFT between Shirley and Harvard. The remaining land areas within Devens are mostly either developed or were previously developed. Remediation of contaminated sites across Devens have largely been done by now, although some areas still need work prior to redevelopment. This working paper is written badly, overall. In addition, there is no discussion of trails, recreation, and connections between open spaces – either existing or desired. There needs to be more about wildlife habitat, water quality and topography. What about some relevant geology, such as the fact that the Oak Hill ridge is an earthquake fault? What is the history of seismic activity there? There also needs to be something about vegetation and plants in Harvard. 14