BBI 3207 Language in Literature

advertisement

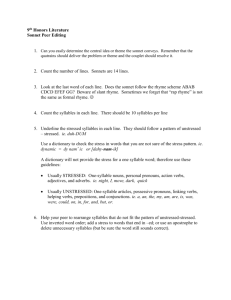

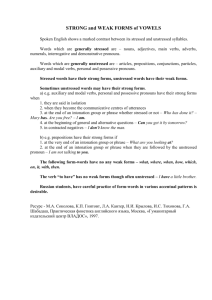

Pusat Program Luar/FBMK UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA Program Bersemuka I Semester 2 2012/13 Kursus: BBL 3207 (LANGUAGE IN LITERATURE) 23 FEBRUARI 2013 BBL 3207 Language in Literature: An Overview Course Synopsis This course covers the interconnections between language and literature. It introduces the use of language in literary texts as a methodical approach in the study of literature, and explores definitions of literature and literariness. The course traces the development of the study of literature which focuses on language from traditional literary criticism to the study of style or stylistics in linguistic criticism. It also examines the value of a linguistic method in reading literature. BBL 3207 – Course Objectives By the end of the course, students will be able to: 1. analyse the interconnections between language and literature(C4), 2. explain the main concepts in the study of language in literary texts (P2), 3. discuss the value of using linguistics as a methodology in reading literature (A4) and, 4. accept new ideas and develop autonomous learning (LL) Topics for 1st half of semester: 1. Introduction: connection between language and literature 2. Foregrounding: Deviation and parallelism 3. Structure: Shapes and patterns 4. Choice of lexical: figurative expressions 5. Sentence structure Assessment 1. 2. 3. 4. Assignment I Mid-Semester Exam Assignment 2 Final Exam 20% 20% 30% 30% • Ordinary language –makes an ordinary use of the possibilities of language design. –made up of many kinds of normative structures • Literary language – makes an extraordinary use of these possibilities this makes the text more memorable – Particular linguistic patterning – Extends and modifies normative structures of language in unusual ways In reading a text, we create a perception of that text. The perception of a literary text is affected by language design, and by the relationship of the text to the literary tradition NORMAL PARADIGM we burn paper we burn wood we burn oil we burn fuel ABNORMAL PARADIGM we burn daylight The object of “burn” has to denote a concrete, combustible material or be a more general term for such materials. What does it mean by “burn daylight”? ‘burnt’ destroyed/used up Possible meaning = we are using up daylight (metaphor) “we burn daylight” Consider the context: - Romeo and Juliet: Montagues gatecrashing Capulet ball (first meeting of R&J) - Reference to torches: burning is literal, daylight is metaphorical a joke Combination of linguistic, contextual and general world knowledge basis for inferring an appropriate interpretation What seems to distinguish literary from nonliterary usage may be the extent to which the phonological, grammatical and semantic features of the language are salient, or foregrounded in some way. Foregrounding • Foregrounding is a significant literary stylistic device based on the Russian Formalist's notion that the very essence of poeticality lies in the "deformation" of language. • "Foregrounding" literally means "to bring to the front." • The writer uses the sounds of words or the words themselves in such a way that the readers' attention is immediately captivated. Foregrounding • Foregrounding works in two ways: 1. by distortion against a norm, 2. by imposing regularity in grammatical patterns over and above those designated by the language repetition or parallelism. Distortion can be studied under deviation, and can take place at any ‘level’ of language i.e. lexical, grammatical, phonological, historical, graphological, semantic and others (Leech :1981). What is ‘foregrounding’? • In a purely linguistic sense, the term ‘foregrounding’ is used to refer to new information, in contrast to elements in the sentence which form the background against which the new elements are to be understood by the listener / reader. 14 • In the wider sense of stylistics, text linguistics, and literary studies, it is a translation of the Czech aktualisace (actualization), a term common with the Prague Structuralists. – In this sense it has become a spatial metaphor: that of a foreground and a background, which allows the term to be related to issues in perception psychology, such as figure / ground constellations. 15 • The English term ‘foregrounding’ has come to mean several things at once: – the (psycholinguistic) processes by which - during the reading act - something may be given special prominence; – specific devices (as produced by the author) located in the text itself. It is also employed to indicate the specific poetic effect on the reader; – an analytic category in order to evaluate literary texts, or to situate them historically, or to explain their importance and cultural significance, or to differentiate literature from other varieties of language use, such as everyday conversations or scientific reports. 16 • Thus the term covers a wide area of meaning. • This may have its advantages, but may also be problematic: which of the above meanings is intended must often be deduced from the context in which the term is used. 17 Devices of Foregrounding • Outside literature, language tends to be automatized; its structures and meanings are used routinely. • Within literature, however, this is opposed by devices which thwart the automatism with which language is read, processed, or understood. • Generally, two such devices may be distinguished, deviation and parallelism. 18 • Deviation corresponds to the traditional idea of poetic license: the writer of literature is allowed - in contrast to the everyday speaker to deviate from rules, maxims, or conventions. – These may involve the language, as well as literary traditions or expectations set up by the text itself. – The result is some degree of surprise in the reader, and his / her attention is thereby drawn to the form of the text itself (rather than to its content). – e.g. neologism, live metaphor, or ungrammatical sentences, as well as archaisms, paradox, and oxymoron 19 • Devices of parallelism are characterized by repetitive structures: (part of) a verbal configuration is repeated (or contrasted), thereby being promoted into the foreground of the reader's perception. – e.g., rhyme, assonance, alliteration, meter, semantic symmetry, or antistrophe. 20 Phonological deviation 1. Syllable omission “Goody, goody. Pay’er back for all those “Rise an’ Shines.”(Lies down, groaning) You know it don’t take much intelligence to get yourself into a nailed-up coffin, Laura. But who in hell ever got himself out of one without removing one nail?” (Tom, 175) “Pay’er”(=pay her ), “Rise an’ Shines”(=Rise and Shine) (from The Glass Menagerie) Levels of language • Language is not merely a mass of sounds and symbols, but is instead an intricate web of levels, layers and links. Levels of Language 1 Phonology; Phonetics: The sound of spoken language; the way words are pronounced 2 Graphology The patterns of written language; the shape of language on the page 3 Morphology The way words are constructed; words and their constituent structures 4 Syntax; grammar The way words combine with other words to form phrases and sentences 5 Lexical analysis; lexicology The words we use; the vocabulary of a language 6 Semantics The meaning of words and sentences 7 Pragmatics; discourse analysis The way words and sentences are used in everyday situations; the meaning of language in context. “That puppy’s knocking over those pot plants!” Graphology: Roman alphabet, in a 12 point emboldened ‘Georgia’ font. Exclamation mark suggests an emphatic style of vocal delivery. Phonology: Potential for significant variation in much of the phonetic detail of the spoken version (e.g. the /t/ vs. ‘glottal stop’ ; /r/ variations ; /ing/ vs. /in/ ). The social or regional origins of a speaker may affect other aspects of the spoken utterance. Morphology: 3 constituents: two root morphemes (‘pot’ and ‘plant’) and a suffix (the plural morpheme ‘s’), making the word a three morpheme cluster. “That puppy’s knocking over those pot plants!” Grammar: A single ‘clause’ in the indicative declarative mood. It has a Subject (‘That puppy’), a Predicator (‘’s knocking over’) and a Complement (‘those potplants’). Semantics: The demonstrative words ‘That’ and ‘those’ express physical orientation in language by pointing to where the speaker is situated relative to other entities specified in the sentence( deixis) - suggest that the speaker is positioned some distance away from the referents ‘puppy’ and ‘potplants’. Pragmatic: This sentence in a two-party interaction will be understood as a call to action on the part of the addressee. Yet the same discourse context can produce any of a number of other strategies – compared with “Sorry,but I think you might want to keep an eye on that puppy..’ (politeness) Phonological deviation 2. Pronunciation deviation from the norm Often happens to interjection, which is deliberately pronounced longer, expressing a stronger emotion When Laura and Jim talks about her unicorn, her long answer shows that she has a deep feeling toward the glass collection. “Mmm-hmmm!” (Laura, 205) (from The Glass Menagerie) Phonological deviation 3. Done deliberately in regard to the rhyme, just to keep the poems rhymed. e.g. wind (N) / wind / wind (V) / waind/ Graphological Deviation • Related to type of print, grammetrics, punctuation, indentation, etc. 1. Parenthesis – explains a specific action / certain / separate situation, When Amanda called Tom to be seated by the table, Tom’s reply showed his reluctance to his mother. “Coming. Mother.” (He bows slightly and withdraws, reappearing a few moments later in his place at the table.) (Tom, 164) Graphological Deviation 2. Capital “What’s the matter with you, you---big---big---IDIOT!” (Amanda, 172) Phonological and graphological deviation are often closely linked. This is because authors sometimes use respelling to provide information about how something sounds when spoken aloud, often to capture (and emphasize) regional or social variation. ‘Man….dis life no easy’ (Zadie Smith 2000) Graphological Deviation • Poets often disregard the rules of writing. They write words in such a way without any boundaries in lines, space, or rhyme ~ E.E. Cumming ~ seeker of truth follow no path all paths lead where truth is here Lexical Deviation • The coining of entirely new words (neologism) When he awakened under the wire, he did not feel as though he had just cranched. Even though it was the second cranching within the week, he felt fit (Cordwainer Smith 1950). The prefix fore is applied to verbs like ‘see’ and ‘tell’. T.S. Eliot uses the term ‘foresuffer’. • Functional conversion of word class But me no buts (Henry Fielding 1730) Syntactical Deviation • Poet disregards the rules of sentence i. fastened me flesh ii. A grief ago (Dylan Thomas) iii. “the achieve of, the mastery of the things” (Hopkins, the Windhover) • Typical word order can be altered to produce particular effects What dire Offence from am’rous Causes springs (Alexander Pope 1714) Morphological Deviation • Involves adding affixes to words which they would not usually have, or removing their ‘usual’ affixes; • Breaking words up into their constituent morphemes, or running several words together so they appear as one long word Morphological Deviation a billion brains may coax undeath from fancied fact and spaceful time (e.e. cummings 1960) coldtonguecoldhamcoldbeefpickledgherkinssaladfrenchrollsc resssandwichepottedmeatgingerbeerlemonadesoda water (Kenneth Grahame 1908) Semantic deviation • Tranference of meaning • phrase containing a word whose meaning violates the expectations created by the surrounding words e.g., “a grief ago” (expect a temporal noun) “in the room so loud to my own” (expect a spatial adjective) Semantic Deviation 1. Simile - describes one thing as another using such words “like” or “as”. Simile also has the power of making language visual and vivid. Laura’s separation increases till she is like a piece of her own glass collection, too exquisitely fragile to move from the shelf. (Glass Menagerie, 161) Semantic Deviation 2. Metaphor – one thing describes another without the use of ‘like’ or ‘as’ “So it is! A little silver slipper of a moon. Have you made a wish on it?” (Amanda, 182) Repetition • Another method of foregrounding • Repeated structure Blow, blow, thou winter wind (Shakespeare, As You Like It) Wind is greater than usual / the speaker has stronger feelings about it than usual Repetition No pain felt she; / I am quite sure she felt no pain (Robert Browning, Porphyria’s Lover) Foreground the notion that the murder caused no physical discomfort to the victim, and thus signals once more the fact that the speaker might be disturbed, might be distorting the truth, and might not be giving an accurate account of the events narrated. Parallelism • Parallel structure joins together two or more recognizably similar, yet not identical structures • Repeated elements • Can occur at all levels of language (phonological, syntactic, morphological etc.) But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities (Isaiah, 53, v) Phonological parallelism • Rhyming verse • Alliteration, assonance, consonance "the silken sad uncertain rustling of each purple curtain." (Edgar Allen Poe, The Raven) Severus Snape," "Luna Lovegood," "Rowena Ravenclaw (characters in Harry Potter series) Syntactic / grammatical Parallelism "Thinking less, feeling more. Doing less, being more. Fearing less, loving more.“ Also, lexical parallelism i.e. ‘less/more’ word phrase clause The birds are in their nests and in their nests they sing. Each morning we sing, each morning we dance, and each morning we pray. Parallelism and effect Parallelism is more than just a repetition of sentence structure. The thoughts expressed by the repeating pattern are also repeated. When we talk of things being in parallel, then the things are of equal force and have the same tone. He was a tender young man, he was a gentle young man, he was an affectionate young man. He was the man everyone wanted. In the example above, the repeating thought is that of a young man of very warm affection. Parallelism in prose aims at basically two things: 1. Reinforcing ideas of importance and 2. Making the text more pleasurable to the reader. In the first instance, if the writer wants to reinforce a certain idea or thought, he will repeat it by using a cyclic pattern: he will repeat sentence structure or word order. The overall effect is that the reader will notice the point that he wants to emphasise and pay particular attention to it. Parallelism and effect • Parallelism in prose also aims at pleasuring the reader. We are naturally musical by nature and are sensitive to rhythm. Not only do we notice rhythmical patterns, but we also enjoy them. Thus, a passage imbued with parallelism is enjoyable and memorable. Parallelism and effect It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to heaven, we were all going direct the other way... (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities? ) The language of poetry Little Bo-peep Has lost her sheep And doesn’t know where to find them Leave them alone And they will come home Waggling their tails behind them Fair is foul and foul is fair Hover through wind and murky air Forms of sound patterning • Rhyme: full rhyme, incomplete rhyme • Alliteration • Assonance • Consonance • Repetition • Rhyme: – two words rhyme if their final stressed vowel and all following sounds are identical; – two lines of poetry rhyme if their final strong positions are filled with rhyming words. |Humpty |Dumpty |sat on a |wall |Humpty |Dumpty |had a great |fall |All the king’s |horses and |all the king’s |men |Couldn’t put |Humpty to|gether a|gain 47 Full rhyme • Sometimes known as perfect, true or exact rhyme. This is a case when the stressed vowels and all following consonants and vowels are identical, but the consonants preceding the rhyming vowels are different e.g. chain, drain; soul, mole. In other words this is a case of near-exact repetitions of end-sounds. Incomplete rhyme • Also known as half-rhymes, which are not exact repetitions but are close enough to resonate e.g. supper, blubber. • Alliteration: repetition of the initial consonant of a word – Magazine articles: “Science has Spoiled my Supper” and “Too Much Talent in Tennessee?” – Comic/cartoon characters: Beetle Bailey, Donald Duck – Restaurants: Coffee Corner, Sushi Station – Expressions: busy as a bee, dead as a doornail, good as gold, right as rain, etc... – Novels: Godric Gryffindor, Helga Hufflepuff, Rowena Ravenclaw, Salazar Slytherin” 49 Alliteration • The repetition of sound, usually consonant, at the beginning of words. Example: • sweet smell of success, a dime a dozen, bigger and better, jump for joy • And sings a solitary song That whistles in the wind. (Wordsworth) • Assonance: Repetition of vowel sounds to create internal rhyming within phrases or sentences – The sound of the ground is a noun. – Hear the mellow wedding bells. (Poe) – And murmuring of innumerable bees (Tennyson) – The crumbling thunder of seas (Stevenson) – That solitude which suits abstruser musings (Coleridge) – Dead in da middle of little Italy, little did we know that we riddled some middle men who didn't do diddily. (Big Pun) 51 • Consonance: The repetition of two or more consonants using different vowels within words. – All mammals named Sam are clammy – And the silken sad uncertain rustling of each purple curtain (Poe) – Rap rejects my tape deck, ejects projectile / Whether jew or gentile I rank top percentile. (Hiphop music) 52 Onomatopoeia • a word that imitates the sound it represents • Example: splash, wow, gush, kerplunk • Examples: Over the cobbles he clattered and clashed in the dark inn-yard, / He tapped with his whip on the shutters, but all was locked and barred; Tlot tlot, tlot tlot! Had they heard it? The horse-hooves, ringing clear; / Tlot tlot, tlot tlot, in the distance! Were they deaf that they did not hear? ("The Highwayman" by Alfred Noyes) ONOMATOPOEIA • Words that imitate the sound they are naming BUZZ • OR sounds that imitate another sound “The silken, sad, uncertain, rustling of each purple curtain . . .” • Repetition: – “Words, words, words.” (Hamlet) – “This, it seemed to him, was the end, the end of a world as he had known it...” (James Oliver Curwood) – “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills… we shall never surrender.” (Winston Churchill) • “What lies behind us and what lies before us are tiny compared to what lies within us.” (Ralph Waldo Emerson) 55 Rhythm • The regular periodic beat. • “a unit which is usually larger than the syllable, and which contains one stressed syllable, marking the recurrent beat, and optionally, a number of unstressed syllables” (Leech (1969): 105). • It may involve a succession of weak and strong stress; long and short; high and low and other contrasting segments of utterance. Rhythm can occur in prose as well as in verse. Meter • Meter is a type of rhythm of accented and unaccented syllables organized into feet, aka patterns. • It is determined by the character and number of syllables in a line. Meter is also dependent on the way the syllables are accented. Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? (Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 18”) • The above line consists of ten syllables that show a pattern of unstressed and stressed syllables: 1st syllable unstressed, 2nd syllable stressed, 3rd syllable unstressed…. 10th syllable. The unstressed syllable is underlined while the stressed syllable is in bold (Cumming 2006). Foot – stress patterning • A foot is made up of a pair of unstressed and stressed syllables. Thus, the above line altogether contains five feet (see below): 1 2 3 4 5 Shall I..|.. compare |.. thee to..|.. a sum..|.. mer’s day? Stress patterning • • • • • • Iamb: 2 syllables, unstressed + stressed Trochee: 2 syllables, stressed + unstressed Anapest: 3 syllables, 2 unstressed + stressed Dactyl: 3 syllables, stressed + 2 unstressed Spondee: 2 stressed syllables Pyrrhic: 2 unstressed syllables 59 5 types of Feet Iamb (Iambic) Unstressed + Stressed Trochee (Trochaic) Stressed + Unstressed Spondee (Spondaic) Stressed + Stressed Anapest (Anapestic) Dactyl (Dactylic "To be or not to be" Two Syllables (Shakespeare’s Hamlet) "Double, double, toil and trouble." Two Syllables (Shakespeare’s Macbeth) “heartbreak” Two Syllables "I arise and unbuild it Unstressed + Unstressed + Three Syllables again" (Shelley's Stressed Cloud) “Openly” Stressed + Unstressed + Three Syllables Unstressed Metrical patterning • • • • • • • Dimetre: 2 feet Trimetre: 3 feet Tetrametre: 4 feet Pentametre: 5 feet Hexametre: 6 feet Heptametre: 7 feet Octametre: 8 feet 61 Meter depends on the type of foot and the number of feet in a line. Below are the types of meter and the line length: Monometer Dimeter Trimeter Tetrameter Pentameter Hexameter Heptameter Octameter 1 One Foot Two Feet Three Feet Four Feet Five Feet Six Feet Seven Feet Eight Feet 2 3 4 5 Shall I..|.. compare |.. thee to..|.. a sum..|.. mer’s day? Practice: Here's an example of how a line by Shakespeare is divided into feet: from FAIR | est CREA | tures WE | deSIRE | inCREASE Intimations of Immortality – Robert Frost THERE was a time when meadow, grove, and stream, The earth, and every common sight, To me did seem Apparell'd in celestial light, The glory and the freshness of a dream. It is not now as it hath been of yore;— Turn wheresoe'er I may, By night or day, The things which I have seen I now can see no more. Choice of lexical: Figurative expressions • Friends, Romans and Countrymen, lend me your ears… Anthony in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar 65 Simile O, my luve is like a red, red rose, That’s newly sprung in June; O, my luve is like the melodie That’s sweetly play’d in tune. Robert Burns (1759-96) 66 Metaphor All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances. And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages … William Shakespeare (1564-1616) Metonymy There is no armour against fate; Death lays his icy hand on kings; Sceptre and Crown Must tumble down And in the dust be equal made With the poor crooked Scythe and Spade. James Shirley (1596-1666) A figure of speech that consists of the use of the name of one object or concept for that of another to which it is related, or of which it is a part, Synecdoche They were short of hands at harvest time. (part for whole) Have you any coppers? (material for thing made) He is a poor creature. (genus for species) He is the Newton of this century. (individual for class) A figure of speech in which a part is used for the whole or the whole for a part, the special for the general or the general for the special Sentence Structure Checking our grammatical intuitions We are going to look at three clauses, or simple sentences, taken from Ted Hughes's 'Esther's Tomcat', all of which describe the cat. Daylong this tomcat lies stretched flat As an old rough mat, no mouth and no eyes. Continual wars and wives are what Have tattered his ears and battered his head. Like a bundle of old rope and iron Sleeps till blue dusk. Then reappear His eyes, green as ringstones [Daylong this tomcat …. Sleeps till blue dusk.] Then reappear his eyes…. Over the roofs go his eyes and outcry. His eyes and outcry go over the roofs. The tomcat still grallochs the odd dog on the quiet, will take the head clean off your simple pullet. Is unkillable. What is deviant about this sentence? Grammatical structure and grammatical function The two sentences below use exactly the same words, but clearly mean different things. • John kisses Mary • Mary kisses John What is it about these two sentences which gives rise to the different meanings? NP Subject John Mary VP Predicator kissed kissed NP Object Mary John 'John' and 'Mary' have different grammatical functions in the sentences Functions of words and phrases in sentences Simple sentences and clauses in English are made up of five functional elements: Subjects (S) Predicators (P) Objects (O) Complements (C) Adverbials (A). Although these five elements do not turn up in every sentence (we will begin to see why below), they have a strong tendency to occur in the above order. SPOCA SPOCA The SPOCA elements are functional constituents of sentences. In the simple cases, they each consist of a phrase, but those phrases 'do different jobs' (i.e. have different functions) in sentences and clauses. SPOCA Element Predicators consist of verb phrases (e.g. 'ate', 'had been eating', 'is', 'was being') which can be used to express tense and aspect) function as The centre of English sentences and clauses, around which everything else revolves They express actions (e.g. 'hit'), processes (e.g. 'changed', 'decided') and linking relations (e.g. 'is', 'seemed') They are the most obligatory of English sentence constituents Examples Mary loves John (transitive predicator), John had been running (intransitive predicator), John seems quiet (linking predicator) SPOCA Element Subjects consist of noun phrases (NPs) (e.g. 'a student', 'John') function as The topic of the sentence, and the 'doer' of any action expressed by a dynamic predicator and normally come before that predicator . Subjects are the next most obligatory element after predicators Examples Mary loves John, The exhausted student had been running, John seems quiet SPOCA Element Objects consist of noun phrases (NPs) function as the 'receiver' of any action expressed by a dynamic predicator, where relevant and normally come immediately after that predicator. Objects are obligatory with transitive predicators (but do not occur with intransitive or linking predicators) Examples Mary loves John, The exhausted student had eaten all his food, Mary has the biggest ice cream Transitive predicators: predicators that require an object (I like pies) Intransitive predicators: predicators that can be used without a direct object. Verbs like come and go and die do not need objects. Contrast verbs like 'make' and 'catch', which are transitive. Some verbs can function both intransitively and transitively, eg. reading. SPOCA Element Complements consist of noun phrases (e.g. 'a student') or adjective phrases (e.g. 'very happy') and normally come immediately after a linking predicator (when they are subject complements) or an object (if they are object complements) Complements are obligatory with linking predicators function as the specification of some attribute or role of the subject (usually) or the object (sometimes) of the sentence Examples John is a student, The exhausted student is ill, Mary made her mother very angry SPOCA Element Adverbials consist of adverb phrases (AdvPs: e.g. 'soon', 'then' 'very quickly', prepositional phrases (PPs: e.g. 'up the road', 'in a minute' or noun phrases (e.g. 'last Tuesday', 'the day before last') function as the specification of a condition related to the predicator (e.g. when, where or how the predicator process occurred) Adverbs are the most optional of the SPOCA elements and can normally occur in more positions than the other SPOCA elements, though the most normal position for most adverbials is at the ends of clauses Examples Then John walked up the road, The exhausted student became ill last Thursday, Next Mary stupidly made her mother very angry on her wedding anniversary What phrases will we find in each of the sentence elements? S Noun Phrase P Verb Phrase O Noun Phrase C Adjective Phrase or Noun Phrase A Adverb Phrase or Prepositional Phrase or Noun Phrase What are the most common (conventional) orderings of the sentence elements? Sentence John / laughed John / ate / the student John / is / crazy John / laughed / mysteriously John / ate / some more students / on Thursday The rest of the students / voted John / maniac of the year The students / gave / John / his bus fare to the asylum SPOCA Dr SPOCA!! S = SUBJECT A Noun Phrase which refers to the entity which is the topic of the sentence (what the sentence is about), and if the predicator of the sentence is a dynamic verb, the subject is the "doer" of the action. Usually comes first in the sentence, before the Predicator. P = PREDICATOR A Verb Phrase which expresses the action/process or relationship in the sentence. O = OBJECT A Noun Phrase which refers to the entity which is the recipient of the action/process. Only occurs with transitive Predicators. Usually comes after the Predicator. C = COMPLEMENT A Noun Phrase or Adjective Phrase which normally comes after a linking Predicator and expresses some attribute or role of the SUBJECT. Sometimes it expresses an attribute or role of the OBJECT. Almost always comes after the Predicator. A = ADVERBIAL An Adverbial, Prepositional or Noun Phrase which usually specifies some condition related to the Predicator, e.g. when, where or how some action occurred. It is by far the most mobile of the sentence elements, and can occur in many different positions in a sentence (the other four sentence elements are much more fixed). Its most normal position is at the end of the sentence, however. Hence the ordering S-P-O-C-A • Notice that unusual orderings are deviant and so produce foregrounding. Consider, for example: (i) Crazy John is. (ii) with not a soul having seen us Analysing some simple sentences using SPOCA analysis • (i) Work out what kind of phrase each constituent is (NP, VP, AdjP, AdvP, PP) • (ii) Show the SPOCA structures of the sentences they occur in. Analysing some simple sentences using SPOCA analysis 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. John loves Mary. Mary loves John. John was very annoyed. The hungry student hates overcooked cabbage. The telephone rang. The cheerful woman was kissing her radiant husband with great abandon. 7. Mary lifted the receiver angrily within two seconds. Thank you for listening… All the best! Dr. Zalina Mohd Kasim E-Mail: zalina@fbmk.upm.edu.my Phone: 03-89468733 FBMK Room No. A153 (1st Floor, Language Studies Block, Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication UPM) Recommended Reading • Simpson, P. (2004) Stylistics: a Resource Book for Students. London: Routledge. • Short, M. (1996) Exploring the Language of Poems, Plays and Prose. London: Longman. • Leech, G. N. (1969) A Linguistic Guide to English Poetry. London: Longman. • Simpson, P. (1997) Language through Literature: an Introduction. London: Routledge. • Cummings, M. & R. Simmons (1983) The Language of Literature: a Stylistic Introduction to the Study of Literature. Oxford: Pergamon Press. • Culpeper, J., M. Short, & P. Verdonk (1998) Exploring the Language of Drama: from text to context. London: Routledge. • Verdonk, P. (2002) Stylistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. LET’S LOOK AT THE ASSIGNMENT