Instructional Design, Course Planning and Developing the Syllabus

advertisement

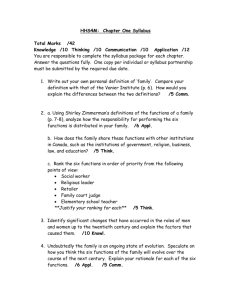

Designing Your Course: Instructional Design, Course Planning, and Developing the Syllabus Danielle Mihram, Ph.D. Distinguished Faculty Fellow USC Center for Excellence in Teaching dmihram@usc.edu Effective Course Design Effective course design includes the following key elements: – (a) Determining what you want your students to learn and how you will measure what they are learning; and – (b) Selecting a set of activities, assignments, and materials that will help you lead these students in their learning. At the end of this workshop, instructors should be prepared to produce a syllabus which: • Articulates specific aims and objectives for a course in their field • Identifies the relationship between course objectives, course content, and sequencing of material • Demonstrates how teaching effectiveness is related to student assessment and course objectives • States clearly defined mutual expectations • Is clear, coherent, and comprehensive. A Useful and Effective Syllabus … Requires reflection and analysis before instruction begins Provides a plan that conveys the logic and organization of the course; Includes content, process, and product goals Provides students with a way to assess the whole course its rationale, activities, policies, and scheduling Clarifies instructional priorities Defines and discusses the mutual responsibilities for the instructor and the students in successfully meeting course goals Allows students to achieve high degrees of personal control over their learning Is much more than a practical document, it has conceptual and philosophical components Serves as a contract for learning Overview Instructional design & Course planning: A systemic approach Planning – Course content – Course objectives • The Teaching Goals Inventory – Group work – Learning objectives and outcomes Instructional strategies for student engagement and lifelong learning -- Issues of Assessment – Examples of assessment tools Identifying and assembling resources Syllabus checklist Useful resources Instructional Design & Course Planning: A Systemic Approach A systemic approach to course design and planning includes five (5) steps): 1. Analyzing: – The situational context of your course: • The conditions of your teaching situation • The characteristics of the students (both student organization and grouping) • The resources at your disposal 2. Planning: – – The course content The course syllabus • • The course objectives (Formulating your course and what your students will learn) The student learning outcomes Instructional Design & Course Planning A Systemic Approach 3. Conducting: – Selecting appropriate and effective teaching methods – Ongoing classroom assessment of your students’ learning 4. Assessing: 1. The course at mid-term 2. The course at the end of term 5. Reflecting on your teaching Course design includes the following “Instructional Commonplaces” – Learner – Teacher – Subject matter – Social milieu (learning context) – Evaluation Analyzing Conditions of your teaching situation: – What official need(s) is the course to fulfill? e.g.: – Meet the needs of the labor market? – Satisfy the requirements of a national accreditation organism? – Update old content and respond to important developments in a modern field? – What is the course’s scope within the general program of study? (How does your course begin? Why does it begin and end where it does? – The requirements of subsequent courses Analyzing (Cont’d) The characteristics of your students: – Diverse academic profiles? (the courses they have taken; the content and pedagogical organization of the previous courses) – The degree of homogeneity of the enrolling students – Their professional (and personal) expectations of the course – Do the students know each other, and have they worked together previously? The resources at your disposal: – Technological support [IT support] for web-based teaching, for multimedia instruction, or for distance learning? • Use of “smart rooms? – Departmental (or university) support for field trips or out of class activities? – Honoraria for guest speakers? Planning Initial questions to ask when determining course content: What are the core scholarly, or scientific, or field-specific findings and assumptions? What are the main points of arguments? What are the key bodies of evidence? What is the context of the course within the larger curriculum framework? Planning (Cont’d) (Initial questions to ask when determining course content:) – Established course or new? – Level of course (1st year? Upper division? Graduate level?) – Is the course required or elective? – Based on textbook and/or course pack? – Requires activities outside of class? Overview Instructional design & Course planning: A systemic approach Planning – Course content – Course objectives • The Teaching Goals Inventory – Learning objectives Instructional strategies for student engagement and lifelong learning -- Issues of Assessment – Examples of assessment tools Identifying and assembling resources Syllabus checklist Useful resources Planning: Course Content • Be clear about what is most worth knowing (What do students need to know in order to derive maximum benefit from this educational experience?) – Describe the content that students will be required to know – Discuss the content that you will make available to support individual student inquiry or projects – Provide content that might be of interest to a student who wants to specialize in this area • Develop a conceptual framework (theory, theme, controversial issue) to support major ideas and topics • Decide what topics are appropriate to what types of student activities and assignments Planning: Course materials Selecting pertinent course materials What do you and your students do as the course unfolds? About what do you lecture or discuss, or present as case studies? What is left up to the students more generally? What are the key assignments or student evaluations? Developing Course Objectives General objectives: A course objective is a simple statement of what you expect your students to know. • Determining the objectives is the most important aspect of course planning (Ask yourself, “What do students need to know in order to derive maximum benefit from this educational experience? What educational outcomes do I want a graduate of this course to display?). • Plan backwards from where you want students to end in terms of their new knowledge, attitudes, and skills. • List these as learning objectives (student learning outcomes) [“by the end of the course you will be able to…”]. • Design the course in a logical and scaffolded sequence of learning activities (reading assignments, lectures, quizzes, technologymediated experiences, formative assessments…) Developing Course Objectives (Cont’d) Course Objectives are based on various learning modes [the AVK Model of Learning]: • Hearing (Audio), as in lectures, seminars and discussion sections • Seeing (Visual), as in reading and observing • Doing (Kinesthetic), as in performance, practical and laboratory work (which may involve taste and smell as well). (Students learn in highly individual and complex combinations of AVK.) Each discipline and subject has its own “AVK” requirements, but incorporating some A, V, and K learning into your course syllabus not only makes for a more interesting class but, pedagogically speaking, also helps to maximize the learning potential of each student. Developing Course Objectives (Cont’d) Verbs that can be used to help construct concrete objectives for your class. analyze appreciate classify collaborate compare compute contrast define demonstrate direct derive designate discuss display evaluate explain identify infer integrate interpret justify list name organize outline report respond solicit state synthesize (N.B. not an exhaustive list) Examples of Course Goals • Discern the differences between personal writing and writing for academic and other audiences, and show awareness of and aptitude with voice and style appropriate for these audiences • Understand the relationship of the visual to the textual; learn to "read" images • Integrate technology in a rich and meaningful way into the research and writing process • Encourage students to write for a "real world" audience beyond the classroom, if possible for campus or local publication. Actual Examples of Course Goal Statements (for you to evaluate) "Fin de sicle [sic] 1800, 1900, 2000: Three Modern Turns in Mythic National Cultures” … we will see how each era privileges certain classes of texts, defines the individual, the citizen, and the human in particular ways, inscribes that individual into the public sphere of the nation through education and other institutions, and offers a vision of history that legitimizes or challenges the group's identity. We will learn as scholars how to situate central texts of culture within precise, illuminating historical, sociological, and narratological contexts, in awareness of how ideological premises become naturalized by disciplines, theories, and the institutions adapting them to the service of the nation, as well as by a characteristic "order of texts" (Chartier) -- a set of textual or artifactual "performances" that disseminated those ideologies. http://www.utexas.edu/courses/arens/1800/1800index.html Actual Examples of Course Goal Statements (for you to evaluate) Principles of Psychology The goal of this course is to provide a broad, general introduction to psychology, which is the scientific study of behavior and mental processes. (…) You should emerge from the course with an increased awareness of the broad range of phenomena investigated by psychologists and with a greater ability to understand and critique psychological research. Special emphasis will be placed on applying psychological principles to everyday life. http://www.southwestern.edu/~giuliant/intro.html Fundamentals of Cognitive Neuropsychology In this course, we first will examine traditionallydefined topics in cognitive psychology (e.g., visual perception, attention, executive function, memory, motor control, language, consciousness), and address: (a) how available cognitive theories have shaped the investigation of cognitive disorders in brain damaged patients, and (b) how the resulting neurological data has shaped (or reshaped) cognitive theory. Although the focus of this course will be on findings from studies of cognitive disorders in patients with localized brain damage, we will also seek converging evidence from complementary techniques that allow examination mind-brain relationships in normal individuals, including functional neuroimaging (e.g., PET, fMRI) and neuromonitoring (e.g., ERP). http://www.columbia.edu/cu/psychology/courses/syllab i/3480.html Actual Examples of Course Goal Statements (for you to evaluate) Corporate Finance This course provides an introduction to the modern theory and practice of corporate finance. Marketing Management The goals of this course are to introduce you to the substantive and procedural aspects of marketing management, and to sharpen your critical thinking skills. Strategy and Organization The primary objective of this course is to help you learn to diagnose management situations so that you will be able to transfer this skill to your work experience. Course Objectives: The Teaching Goals Inventory (TGI) Includes considerations of six major components: 1. Higher order thinking skills 2. Basic academic success skills 3. Discipline-specific knowledge and skills 4. Liberal arts and academic values 5. Work and career preparation 6. Personal development Course objectives: The Teaching Goals Inventory (TGI) Found in: Angelo, Thomas A. & K. Patricia Cross (1993). Classroom Assessment Techniques - A Handbook for College Teachers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (2nd ed.). Course Objectives: The Teaching Goals Inventory (TGI) Purposes of the TGI: • To help college teachers become more aware of what they want to accomplish in individual courses • To help faculty locate classroom assessment techniques they can adapt and use to assess how well they are achieving their teaching and learning goals among colleagues • To provide a starting point for discussion of teaching and learning goals among colleagues See pp. 393-397 in: Angelo, Thomas A. & K. Patricia Cross (1993). Classroom Assessment Techniques - A Handbook for College Teachers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (2nd ed.). Online Access to list: http://www.siue.edu/~deder/assess/cats/tchgoals.html http://fm.iowa.uiowa.edu/fmi/xsl/tgi/data_entry.xsl?-db=tgi_data&-lay=Layout01&-view Course Objectives: The Teaching Goals Inventory (TGI) Group work: Teaching Goals Inventory and Self-scorable worksheet (Handout) A. Each participant: 1. Considers ONE course you are (or will) teach 2. Responds (by circling in pencil) to each item on the TGI in relation to that particular course B. Participants form small groups: Explain your responses to team members C. General discussion: what have we learned? Actual Examples of Course Goal Statements (for you to evaluate) PHYS345 Electricity and Electronics Course Objectives: As a result of this course, I hope that you can better • Realize the importance of electricity and electronics in everyday life and value its benefit to society. • Access the fundamental physics available for dealing with engineering problems in the electrical domain. • Apply selected physical concepts important in designing and using electrical and electronic circuits. • Analyze and solve realistic problems, use mathematical techniques effectively in their solution, and reason accurately and objectively about the physical domain. • Translate verbal and graphical descriptions of physical systems into appropriate mathematical models. • Analyze and draw valid conclusions from experimentally obtained data. • Apply spreadsheet or modeling software to organize data, perform calculations, and display results graphically. • Communicate technical ideas effectively, both in writing and orally. http://www.physics.udel.edu/~watson/phys345/frame/index_syllabus.html Learning Outcomes What your students will learn within the content of a body of knowledge – Each course objective should lead to an actionable learning outcome: A short statement, formulated from the professor’s point of view, beginning with a verb and providing actionable outcomes: • “Introduce students to … so that”; “help student discover … and then” ; “develop the ability to … so as to transfer … to …”; “give students a theoretical and practical overview … to …”. See The Teaching Goals Inventory (TGI) Student Learning Outcomes Specific Objectives Specific objectives: from the student’s point of view (Learning goals and outcomes) What the student must be able to do or achieve during or at the end of a learning situation or section (in order to attain the general objectives). These objectives are linked to each of the course’s themes and general objectives: Permits you to link a given subject and student performance Each objective must be linked to an action or outcome Student Learning Outcomes - Specific Objectives An Example (Course: Using Technology in Science Education) At the end of this course, you should be able to: 1. List and contrast current models of science teaching and learning using technology. 2. Critique current models of teaching and learning using technology in relation to your personal philosophy of science education. 3. Analyze curricular technology models for alignment with published standards. 4. Identify effective assessment models for evaluating technology. 5. Discuss how pro-active strategies can establish safe classroom environments where all students are encouraged to participate and express their views. http://faculty.washington.edu/jrios/TEDUC%20513/General%20Course%20Information.html Actual Examples of Learning Objectives (for you to evaluate) • Be able to compare and contrast earnings and cash flows as measures of performance. • Identify and use three format techniques to increase the effectiveness of a written business communication. • Understand the mechanics of the cash flow statement. • Conduct independent research and write a publishable article for a newspaper or professional journal. • Understand the implementation of SOX on US businesses and the resulting changes. • Prepare and deliver a persuasive presentation using logical and emotional arguments. Actual Examples of Learning Objectives (for you to evaluate) Art History - Survey II Learning Outcomes and Performance Objectives with their methods of measurement as used to determine the students’ mastery of those outcomes.Learning Outcomes/Performance Objectives/Measurements: • • • • A. The student will identify vocabulary, media, and general theories related to the history of art from the 14th century through present day. Evaluation: written assignments, including research papers, and written exams. B. The student will distinguish and classify works of art and architecture within the context of the individual, society, time, place and circumstance within the time frame covered in this course. Evaluation: written assignments, including research papers, museum/gallery visits and written exams. C. The student will describe the material, cultural and conceptual conditions involved in making and using works of art and architecture. Evaluation: written assignments, including research papers, museum/gallery visits and written exams. D. The student will interpret works of art and architecture by synthesizing formal analysis with scholarly research. Evaluation: research papers, exhibit and/or resource critique. http://www.accd.edu/sac/vat/arthistory/arts1304/syllabus.htm For Access to Syllabi in all Fields … Go to: World Lecture Hall http://web.austin.utexas.edu/wlh/browse.cfm Overview Instructional design & Course planning: A systemic approach Planning – Course content – Course objectives • The Teaching Goals Inventory – Group work – Learning objectives Instructional strategies for student engagement and lifelong learning -- Issues of Assessment – Examples of assessment tools Identifying and assembling resources Syllabus checklist Useful resources Instructional Strategies The core question: How to develop a challenging and supportive course climate that builds on students’ interests, exemplifies the big topics in the field, teaches interpersonal and collaborative skills, and develops the capacity for lifelong learning (learning how to learn in the field). – Decide on a mix of strategies to shape basic skills and procedures, present information, guide inquiry, monitor individual and group activities, and support and challenge critical reflection – The chosen strategies must fit with the outcomes you hope to achieve – Examples of general instructional strategies: • Training and coaching • Lecturing and explaining • Inquiry and discovery • Field work and community-based work • Experiential opportunities (such as internships) and reflection (portfolios) Encouraging Active Student Involvement and Lifelong Learning • Are course topics related to content, or process, or both? What embedded activities will help students to learn the tools of the discipline or field? • Activities and products that can involve students in sustained intensive work, both independently and with one a other might include: – Group research projects – Reaction papers on one of several topics provided by the instructor or suggested by the student(s) – Challenging the students to “improve the syllabus” by adding or omitting a reading assignment or two (with a rationale for doing so) • A learner-centered approach changes the students’ role by encouraging acceptance of personal responsibility for learning “intentional learning” (this can be difficult for students who have been educated as passive learners). Considering Issues of Assessment (To be discussed at greater length in another session) • Demonstrations of learning should include multiple ways to represent knowledge and skills • Consider the role and rationale for individual and group assessment opportunities • Provide worked examples and grading rubrics where possible so that all learners know what constitutes good (successful) work • Consider using both formative and summative modes of assessment Examples of Assessment Tools • Products (essays, research reports, other projects) • Performance assessments (music, dance, dramatic performance [e.g., role play], science experiments, demonstrations, debates….) • Process-focused assessment (journals, learning logs, reflective statements, oral presentations) • Assessment of recall and application at the highest cognitive level (Bloom’s et al. taxonomies) • Examine the CET website for more helpful information on assessment: http://www.usc.edu/programs/cet/resources/assessment/ Overview Instructional design & Course planning: A systemic approach Planning – Course content – Course objectives • The Teaching Goals Inventory – Group work – Learning objectives Instructional strategies for student engagement and lifelong learning -- Issues of Assessment – Examples of assessment tools Identifying and assembling resources Syllabus checklist Useful resources Identifying and Assembling Resources • Consider ways to include the full range of “knowledge nodes” (some of which may include alternative and conflicting perspectives). These would include: – Lectures, panel presentations, case studies, demonstrations, facilitation, discussion, online discussion boards – books and readings, films, multimedia, maps, libraries, museums, theaters, studios, labs, databases, Internet sites, …. • Involve outside individuals, communities, or officials for guest lectures and service learning opportunities where appropriate (For example: USC’s Joint Educational project [JEP].) • Assign projects that will tap into students’ personal interpretations by challenging them to search for further information or new, even contradictory, points of view. Overview Instructional design & Course planning: A systemic approach Planning – Course content – Course objectives • The Teaching Goals Inventory – Group work – Learning objectives Instructional strategies for student engagement and lifelong learning -- Issues of Assessment – Examples of assessment tools Identifying and assembling resources Syllabus checklist Useful resources Syllabus Checklist Expanded from Grunert, J. (2007). The Course Syllabus… Course Identifiers Instructor Contact Information Purpose of Course Course Goal and Learning Objectives Course requirements, Prerequisites, Co-requisites Required, Recommended Materials Assignments and Exam Due Dates Evaluation specifics Grading criteria Policies, Expectations Missed exams, quizzes Attendance Other, as required Detailed Schedule Reading list with reference Useful Resources on Course Design and Syllabus Creation Grunert, Judith (2007) The Course Syllabus: A Learning-Centered Approach. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. • Prégent, Richard (2000). Charting Your Course: How to Prepare to Teach More Effectively. Madison, Wisconsin: Atwood (English ed.). Useful Resources on Course Design and Syllabus Creation Angelo, Thomas A. and K. Patricia Cross (1993). Classroom Assessment Techniques – A Handbook for College Teachers. San Francisco, CA: JosseyBass (2nd ed.). Richlin, Laurie (2006). Blueprint for Learning – Constructing College Courses to Facilitate, Assess, and Document Learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus. Useful Resources on Course Design and Syllabus Creation Teaching and Learning Resources on the website of the USC Center for Excellence in Teaching: http://www.usc.edu/programs/cet/resources/ Syllabus and Course Design http://www.usc.edu/programs/cet/resources/creating_syllabi/ USC Office of Curriculum - Sample Syllabus Template http://www.usc.edu/dept/ARR/curriculum/handbook.html Review Instructional design & Course planning: A systemic approach Planning – Course content – Course objectives • The Teaching Goals Inventory – Group work – Learning objectives Instructional strategies for student engagement and lifelong learning -- Issues of Assessment – Examples of assessment tools Identifying and assembling resources Syllabus checklist Useful resources