As its name implies, Windows 3 was not the first release of

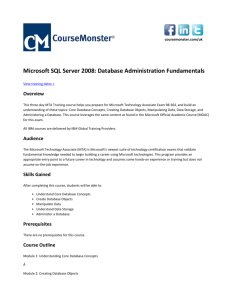

advertisement

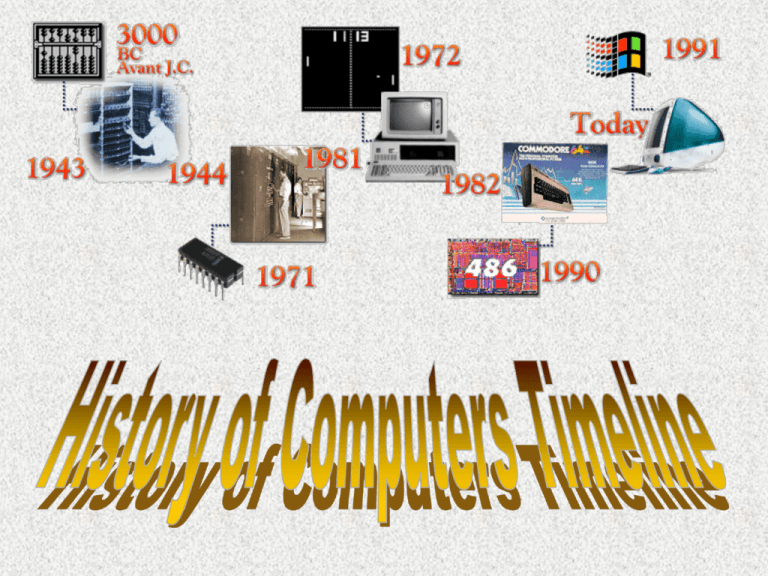

The Abacus The invention of the abacus marks the beginning of computers. For the first time, people use a calculating device to do math. It is thought to have originated between 600 and 500 BC, either in China or Egypt. Round beads, usually made of wood, were slid back and forth on rods or wire to perform addition and subtraction. The abacus is still used in many cultures today. Napier’s Bones In the early 1600s, a Scottish mathematician named John Napier invented a tool called Napier's Bones. These were multiplication tables inscribed on strips of wood or bone. The Pascaline Blaise Pascal invented the first digital calculator to help his father with his work collecting taxes. The user would dial the numbers he wanted to add together and the machine would automatically add them. The result would be shown through six small windows at the top of the machine. The Leibniz Wheel Gottfried Wilhelm Von Leibniz took the Pascaline one step further and invented a similar machine to add, subtract, multiply and divide. The Stepped Reckoner, as Leibniz called his machine, used a special type of gear called a Stepped Drum or Leibniz Wheel, which was a cylinder with nine bar-shaped teeth of incrementing length running parallel to the cylinder’s axis. The drum is rotated using a crank. This movement is then translated by the device into multiplication or division depending on which direction the stepped drum is rotated. The Jacquard Loom Punched cards guided Jacquard's Loom in making complex woven patterns of flowers and leaves into a large cloth. Similarly, Babbage's Analytic Engine would use punch cards to program data "input" into the machine, automating the mechanical steps of calculating numbers, resulting in an "output" on a printed printed page. The Analytical Engine Babbage worked on his Analytical Engine from around 1830 until he died, but sadly it was never completed. It is often said that Babbage was a hundred years ahead of his time and that the technology of the day was inadequate for the task. The organization of the Analytical Engine is virtually identical to that of modern computers having an input section, a central processor that performs arithmetic and logical operations, a memory unit to store information, and an output section to make the results available to the user. Herman Hollerith Herman Hollerith combined the old technology of punched cards (used in the Jacquard Loom) with the, then, new electrical technology of vacuum tubes, to produce a sorting and tabulating machine. In this machine, wires poked through the holes in the punched cards then into cups of Mercury, which completed an electrical circuit and registered the data on the card. The 1880 census took over 7 years to complete. With the help of this machine, the 1890 census was completed in six weeks. IBM In addition to solving the census problem, Hollerith's machines proved themselves to be extremely useful for a wide variety of statistical applications, and some of the techniques they used were to be significant in the development of the digital computer. In 1896 Hollerith founded the Tabulating Machine Company, forerunner of Computer Tabulating Recording Company (CTR). He served as a consulting engineer with CTR until retiring in 1921. In 1924 CTR changed its name to IBM - the International Business Machines Corporation. The Enigma Machine In today's computer world, many of us use encryption technology to keep our data safe from others. But in the 1930's, encryption was a life-or-death matter. As Nazi Germany made war on Europe, its generals and admirals had a secret weapon. It wasn't a bomb or a gun; it was a code machine. The Enigma machine was one of thousands deployed by the Nazis so they could send and receive encoded messages. The wooden box contained dials and wheels that could be set with the day's code instructions. Then, anything transmitted would be in code. But while the war raged on, British intelligence officers were capturing the encoded transmissions and building a computer called Colossus to decipher them. They eventually cracked Enigma's secrets and helped turned the war's tide. Betchley Park and Colossus Bletchley Park was Britain's best kept secret 50 years ago. But without Bletchley Park, World War II would probably have lasted another two years. It was at Bletchley that code-breakers monitored and read the top secret communications between members of the German High Command during the Second World War. It was at Bletchley that Colossus was built. This was Britain's first - and, if the historians at Bletchley are to be believed, the world's first - electronic computer. Americans claim to have been first with ENIAC, but experts insist that Colossus beat this by two years. The reason it isn't in most of the history books is because it was a secret. the hut used by the enigma team ENIAC Electronic Numerical Integrator And Calculator The ENIAC was a largescale, general purpose digital electronic computer. Built out of some 17,468 electronic vacuum tubes, instead of switches and relays, ENIAC was in its time the largest single electronic apparatus in the world. ENIAC was a secret World War II military project to speed up the tedious mathematical calculations needed to produce artillery firing tables for the Army. UNIVAC Universal Automatic Calculator The Universal Automatic Computer or UNIVAC was a computer milestone achieved by Dr. J. Presper Eckert and Dr. John W. Mauchly, the team which invented the ENIAC computer. In 1946, Eckert and Mauchly were contracted by the United States Census Bureau to build a computer to help with the increase in population. They were given $300,000 to build the machine. In 1951, the machine was finally built at a final cost of over one million dollars. UNIVAC was the world's first electronic general purpose data processing computer. The IBM 650 The IBM 650 was the first computer to be mass produced. The 650 only used about 500 vacuum tubes in its central processing unit, and was therefore much smaller and more dependable than the UNIVAC. Because IBM developed a marketing strategy that discounted rentals of the machine to universities, the 650 became the computer around which the new academic discipline of computer science evolved. Minicomputers In 1957a company called Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) was formed. Their original objective was to grab a slice of IBM's business market and sell million-dollar mainframes. Financial realities prevailed, however, and a new plan emerged--build a slightly scaled down computer and sell it for $125,000 to scientific and engineering markets. DEC computers proved successful even in other markets, and by 1969--during the era of miniskirts and miniseries--these computers were universally referred to as "minicomputers.“ Digital Equipment Corporation merged with Compaq in 1998. Today's minicomputer vendors include IBM, Digital/Compaq, and Hewlett Packard. Programming Languages In 1957, the first of the major languages appeared in the form of FORTRAN. Its name stands for FORmula TRANslating system. The language was designed at IBM for scientific computing. Although FORTAN was good at handling numbers, it was not so good at handling input and output, which mattered most to business computing. Business computing started to take off in 1959, and because of this, COBOL (Common Business-Oriented Language) was developed. Integrated Circuits In 1959, the first integrated circuit was created. Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments and Robert Noyce of Fairchild Semiconductor, two separate inventors, unaware of each other's activities, invented almost identical integrated circuits at nearly the same time. An integrated circuit is an assembly of electronic components fabricated in a single unit. This is the PDP-1 – the first digital minicomputer with video display. It was Digital Equipment Corporations first computer. Supercomputers In 1964, IBM introduced the System/360, the first large "family" of computers to use interchangeable software and peripheral equipment. Rather than purchase a new system when the need and budget grew, customers now could simply upgrade parts of their hardware. It was a bold departure from the monolithic, one-size-fits-all mainframe. 1971: 4004 Microprocessor The 4004 was Intel's first microprocessor. This breakthrough invention powered the Busicom calculator and paved the way for embedding intelligence in inanimate objects including the personal computer. In 1976, Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs form Apple Computer and show off the Apple I at the Homebrew Computer Club at Stanford University. The 80’s In July of 1980, IBM representatives meet for the first time with Microsoft's Bill Gates to talk about writing an operating system for IBM's new hush-hush "personal" computer. The first IBM PC ran on a 4.77 MHz Intel 8088 microprocessor. The PC came equipped with 16 kilobytes of memory (expandable to 256k), one or two 160k floppy disk drives, an optional color monitor and a price tag starting at $1,565. Apple Computers The Macintosh debuts in 1984. It features a simple, graphical interface, uses the 8-MHz, 32bit Motorola 68000 CPU, and has a built-in 9-inch B/W screen. Microsoft Windows As its name implies, Windows 3 was not the first release of Microsoft's Windows graphical user interface for PC's. Windows had originally been released in 1985. However, in the past Windows had looked ugly, run slowly and had very little support from third party software developers. Most important of all, however, was that at its big launch in May 1990, Microsoft was able to parade an impressive lineup of major software vendors with applications which ran under Windows 3. Among these were versions of the Microsoft Word word processor and Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, which went on to dominate the personal word processing and spreadsheet markets on both Microsoft Windows and the Apple Macintosh. The bottom line was that a PC running Windows 3 was now almost as easy to use as an Apple Macintosh. Because of this, Windows swept through the PC world like wildfire, and within a year nearly everyone was running it on their PC's Apple Sues Microsoft Apple actually began court proceedings against Microsoft in 1988, when Microsoft released Windows 2. However it wasn't until Windows 3 was released, and Apple immediately expanded its claim to include Windows 3, that the media began to pay major attention to this case. In essence, Apple was arguing that Microsoft Windows breached copyright by being too similar to the Macintosh user interface. The case ended up taking many years and going through several appeals. The final decision, announced in early 95, was that copyright had not been breached. Some people saw this as a good decision because it promoted competition, while others saw it as a terrible decision because it reduced the incentive to develop new innovative technology. This fundamental question is still under debate today, and probably will be forever.