Goal #2: Expansion and Reform (1801

advertisement

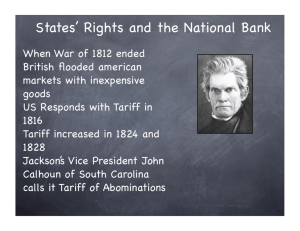

Goal #2: Expansion and Reform (1801-1850), assess the competing forces of expansionism [The Continuing Struggle for Union] 2.01: Analyze the effects of territorial expansion and the admission of new states to the Union 1801-1850 Territorial Expansion, 1790-1824 Treaty of Greenville: After U.S. troops routed the Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. In 1795, the Indians agreed to the treaty that paid them $10,000 per year for their land in southern Ohio and Indiana, and enclaves at Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, and Vincennes, Illinois. Pinckney’s Treaty: Treaty negotiated by Thomas Pinckney, minister to Spain, to settle a dispute over the boundary between the U.S. and Spain in West Florida. Spain claimed all land south of the Tennessee River. The treaty settled on a line at 31 degrees latitude, from the Chattahoochee River to the Mississippi. The Louisiana Purchase As Spain gave its Louisiana Territory to France, President Jefferson worried that Napoleon would close the Port of New Orleans, making trade via the Mississippi, Ohio, and Tennessee Rivers too expensive or impossible. Jefferson planned to buy New Orleans for $9 million, but Napoleon offered all of the Louisiana Territory for $15 million. Although he had no clear constitutional authority to do so, Jefferson made the purchase. Napoleon Signs the Louisiana Cession The total amount of land bought according to the treaty was imprecise, but it included ‘all the lands drained by the waters of the Mississippi River.’ The purchase more than doubled the size of the U.S., extending the nation west to the Continental Divide in the Rocky Mountains. Lewis & Clark Expedition Trip by the Corps of Discovery, led by Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) and William Clark (1770-1838) with the help of Shoshone Indian guide Sacajawea, to explore the West. Although planned well before, it took on new importance after the Louisiana Purchase. It began in St. Louis in 1804, went along the Missouri River through the Rocky Mountains onto the Columbia River and to the Pacific Ocean. Returning to Washington in 1807, the expedition was a great success. They did not find the hoped-for total water route to the Pacific, but Lewis and Clark mapped the territory, brought back animal and plant artifacts, and firmed up the U.S. claim to the region. They also started an explosion of commerce in the region, expanding the fur trade. “The whole of East Florida [must be] seized and held as an indemnity for the outrages of Spain upon the property of our citizens. This done, it puts all opposition down . . . and saves us from a war with Great Britain of some of the Continental powers combined with Spain.” – Andrew Jackson Conquest of Florida: Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795 settled a border dispute with Spain east of the Mississippi. But tensions picked up again as Americans drifted southward testing the line. After repeated skirmishes between Seminoles and American settlers along the border, President Monroe ordered Andrew Jackson to “pacify” the region. Although he had no right to do so, he took over Florida.* With the U.S. in possession of the land, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams backed Jackson. In the Adams-Onis Treaty (1819), Spain gave Florida to the U.S. in return for a part of Texas that the U.S. claimed. The Seminoles continued to fight into the 1840s, but finally were defeated and removed to the Indian Territory. The United States in 1820 American Asserts Its Power Monroe Doctrine: U.S. foreign policy created by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and declared by President James Monroe in his “State of the Union” message to Congress in 1823. It states, “The American continents are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European power.” The doctrine was directed at France, which was eyeing the newly independent republics of South America, and at Russia, which had an interest in Alaska. It succeeded because it had the unofficial backing of Great Britain and the Royal Navy. The Monroe Doctrine demonstrates that the U.S. intended to become an important international power. Goal #2: Expansion and Reform (1801-1850), assess the competing forces of expansionism 2.02: Describe how the growth of nationalism and sectionalism were reflected in art, literature, and language 2.03: Distinguish between the economic and social issues that led to sectionalism and nationalism 2.04: Assess political events, issues, and personalities that contributed to sectionalism and nationalism The First Industrial Revolution 1793-1850 Industrialization: Transformation of an economy from an agricultural base to an industrial base – built largely on mechanization. Although it should not be overstated—the U.S. experienced its first era of industrial development between 1813 and 1837. The development of industries was built on a transportation revolution—the invention of the steamboat (by Robert Fulton) and the coming of railroads. The first substantial industry in America, the textile industry, developed in New England where factories turned southern cotton into textiles. Industrialization also affected farming, as new inventions improved crop production, harvesting, and processing. Cotton Gin Eli Whitney's invention that transformed American agriculture and industry. The problem with cotton cultivation is the seeds embedded in cotton bolls that must be removed before the cotton can be turned into textiles. Before the gin (short for engine), it took a man about a day to process one pound of cotton. Whitney's small gin could process about fifty pounds a day. An enlarged gin could process much more. The gin made cotton cultivation profitable. It sparked a demand for more land on which to grow cotton and thus America expanded. It also reinvigorated a slave labor system that had been in decline since the Revolution. It provided a base for the early industrial revolution in New England in the 1820s. The rise of a textile industry drew the sections closer together as purchaser and supplier, but the relationship was not equally beneficial. The northern economy became more complex, while the South became more dependent on one crop –and became known as the Cotton Kingdom. Revolution in Transportation and Communication Robert Fulton: Inventor of the first commercially successful steamboat—The Clermont which first steamed up the Hudson River in 1807. By 1836, 361 steam-driven paddle wheelers were registered to navigate tributaries of the Mississippi River. The Tom Thumb: First passenger train in the U.S., it was invented by Peter Cooper in 1830 in Baltimore. It ran along rails at the incredible speed of 10 miles an hour, but when challenged to race a horse-drawn wagon, the train broke down. Despite the inauspicious beginning, railroads were faster and came to dominate longdistance travel and commerce in the U.S. over the next two decades. Samuel Morse: Inventor in the U.S. of the telegraph in 1837. The telegraph is an electro-magnetic transmitter that interrupts an electric circuit and allows for transmission of information. The telegraph was separately invented in England. Morse’s more important contribution became the Morse Code, a series of electrical “dots” and “dashes” that became the alphabet of telegraphy. Erie Canal: Man-made waterway, opened in 1826, connecting the Hudson River and New York City to Lake Erie (Buffalo). It opened the West to trade because it linked the Great Lakes as far as Duluth, Minn., and Chicago, Ill., to the Atlantic without having to go through Canada. It lost some of its importance when railroads entered the scene. “E-Ri-E Canal” by the Weavers We were forty miles from Albany Forget it I never shall What a terrible storm we had one night On the E-ri-e Canal Chorus: O, the E-ri-e was a-risin’ And the gin was a-getting’ low I scarcely think we’ll get a drink ‘Til we get to Buffa-lo-o-o ‘Til we get to Buffalo The barge was full of barley The crew was full of rye The captain he looked down at me With a dag’gum wicked eye Chorus The captain he stood up on deck With a spy-glass in his hand The fog it was so dog gone thick That he couldn’t spy the land Chorus Now two days out from Syracuse The vessel struck a shoal We like to all be foundered On a chunk o’ Lackawanna coal Chorus O the cook she was a grand old gal She wore a ragged dress We like to hoist her up the pole As a signal of distress Chorus Now the captain he got married The cook she went to jail And I’m the only son-of-a-sea cook Left to tell the tale Chorus twice Steps to Creating a National Economy: The Marshall Court Fletcher v. Peck (1810): The State of Georgia granted part of the future Alabama and Mississippi to the Yazoo Land Company in 1794. When the public discovered that many legislators had been bribed to make the deal, the people voted them out of office and the new Georgia legislature repealed the grant. But some of the land had already been sold; so the new owners sued for breach of contract. The Marshall Court ruled that the new owners were protected under the Contract Clause (Art. I, Sect. 10). Under this decision, the Supreme Court asserted the power to overturn state laws. Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1816): Virginia case involving inheritance and the Treaty of Paris (1783). To attack Loyalists during the Revolution, a Virginia law said no “enemy” could inherit land. When Martin, a British citizen, tried to sell land he had inherited, Virginia took it. Martin sued and lost in Virginia court. He appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Marshall Court accepted the case, setting the precedent that the U.S. Supreme Court can hear appeals and reverse state court rulings. Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819): Piggy-backing on the Fletcher precedent, the Marshall Court ruled that the State of New Hampshire could not alter the 1769 charter of Dartmouth College because the Court ruled the charter to a contract. Under this decision, corporate charters are protected by the Contract Clause and states may not regulate them. Daniel Webster argued the case on behalf of Dartmouth College. McColloch v. Maryland (1819): Supreme Court decision deriving from Maryland’s attempt to tax federal bank notes. Chief Justice Marshall rejected Maryland’s claim that states had created the federal government, ruling instead that it was created directly by the people (“We the People”). The decision relates to federalism; Marshall ruled that the national government’s power is limited but “is supreme within its sphere of action.” Gibbons v. Ogden (1824): Arising out of a controversy involving Fulton’s steamboat and navigation of the Hudson River. The New York state assembly gave Fulton and his partner exclusive rights (a monopoly) to steamboat traffic on the river. They then granted a contract to Aaron Ogden. But because the Hudson forms the boundary between two states, New York and New Jersey, Thomas Gibbons sued claiming that he should have access to the river also. The Marshall Court unanimously ruled in favor of Gibbons, saying that the Constitution gives sole right to regulate interstate commerce to the federal government and no such power may be exercised by any state. This further established the power of the federal government, as Marshall wanted. It also sparked dramatic development of steamboat navigation and set the precedent for similar questions involving railroads in the 1830s and afterward. Economic Collapse: The Panic of 1819 First national crisis of the boom and bust business cycle in U.S. history, it led to a depression and affected public trust in banks for a generation. As with any economic catastrophe, its causes are complex. The War of 1812 had created more debt for the U.S., but a postwar boom gave the impression of solvency, generating widespread speculation. As usual, there was too little hard currency (specie) in the economy; so banks printed paper money, causing rampant inflation. The expansion of paper money set the stage for potential disaster if anyone decided to ask what the real value of money was. Meanwhile, uncontrolled lending weakened banks to the point where it was said that barely six banks in the country could have met their obligations if they fell due. Added to this, the crudeness of the frontier economy opened opportunities for criminal activity: check-kiting and counterfeiting. Then, in 1818, the price of cotton soared to over 32 cents a pound, causing the British to look for alternative sources in India and Egypt, causing the price in the U.S. to fall to 14.3 cents. The price drop sent shock waves through the economy as debts were called by banks and as demand for other U.S. goods dried up. Loans went unpaid and banks went out of business, causing the economic bubble to burst. Many blamed the Bank of the United States (BUS) for the crash. Under its 1816 charter, the BUS was required to pay out in specie upon request. With too little hard currency available in the U.S., it bought specie from Britain at a premium, putting the BUS in debt, too. When Congress issued a report on the administration of the BUS, the dominoes began to fall. It discovered that many branches of the BUS, notably the Baltimore branch, were rife with corruption. The collapse of the Baltimore branch caused a ripple effect of panic through Maryland and the South, ultimately sending the economy into depression. One of the more important results of the Panic and depression was that for the first time several states enacted relief legislation, including: stay laws, placing a moratorium on collection of debts; and setting minimum appraisal laws, restricting the auction price of defaulted property. The other significant result was a lingering distrust for the BUS. Jacksonian America 1820-1850 Andrew Jackson Henry Clay John C. Calhoun Daniel Webster Andrew Jackson, 1767-1845: Born in the Catawba Valley near the North CarolinaSouth Carolina border, he learned the law in Salisbury before venturing west to Tennessee. A one-time Judge, slave-owner and slave-trader, hero of the Battle of New Orleans, he ran for President in 1824 and, in a four way race, won more of the popular vote but not a majority of the Electoral College, thus leading to what Jacksonians called the “corrupt bargain.” He ran again in 1828, calling himself an agent for the common man and took two-thirds of the electoral vote. In office, he removed any political opponents from government jobs using the patronage power and gave the jobs to his supporters, creating the “spoils system.” He governed as an opponent of centralized government and the American System, and often let personal hatreds interfere with policy. Because of his hatred of Henry Clay and Nicolas Biddle, he killed the Second Bank of the United States. Like most Westerners, he hated Indians and as POTUS he treated them ruthlessly. His hatred for John C. Calhoun determined his response to South Carolina's attempt to nullify a protective tariff in 1833. “Harry of the West,” 1777-1852 Henry Clay was one of the four most important politicians in the U.S. in the first half of the nineteenth century. A Kentuckian, represented the West and was the leading nationalist in Congress from the 1812 war to his death in 1852. He ran for president three times as a National Republican or a Whig, never winning. He held such important positions as Secretary of State and Speaker of the House. At critical points, he put together agreements between the different sections and competing factions in the country, earning the name the “Great Compromiser.” He fashioned the Missouri Compromise (1820-21); the Compromise of 1833--settling the tariff dispute between South Carolina and Congress to end the Nullification Crisis; and the Compromise of 1850. In retrospect, his compromises helped delay what many historians consider the inevitable civil war until the Union was in a position to win. John C. Calhoun, 1782-1850: Born on the frontier of western South Carolina of Scots-Irish stock, Calhoun was a hard-headed politician, he came to represent the South in the federal government from the War of 1812 to the very day of his death in 1850. He was Secretary of War under Monroe and Vice-POTUS to John Quincy Adams and then to Andrew Jackson. He resigned the office, however, in 1831 after a long conflict with Jackson and went on to lead the state’s attempt to nullify the “Tariff of Abominations” in 1833. In 1850, fearing the South would be a permanent minority and forced to bow to the will of the free North and West, he reluctantly called for secession if slavery were not allowed to spread into the territories. Daniel Webster, 1782-1852: Born in New Hampshire, he represented Massachusetts in the Senate. An expert lawyer, he represented Dartmouth College and the federal government in the important 1819 cases involving the right of contract and taxing of federal bank notes. In 1830, he defended the nationalists in a famous debate with South Carolina’s Robert Hayne (John C. Calhoun). As Secretary of State in the 1840s, he negotiated important treaties with Britain and expanded U.S. territory. He was known as the greatest debater in the Senate. So great that Stephen Vincent Benet wrote a play, The Devil and Daniel Webster, in which Webster debated Satan in court and won the case. The American System: Clay’s plan to strengthen the nation. It called for creating a new national bank, imposing protective tariffs, and spending federal tax money on internal improvements, such as building the National Road (from Cumberland, MD to Vandalia, IL) to unite the country, improve trade and national defense. As the sections split over internal improvements in the 1820s, it began the decay of the “era of good feelings.” Clay and John Quincy Adams represented a Nationalist-Republican faction, while Jackson and John C. Calhoun represented a Democratic-Republican faction. Those who opposed internal improvements usually balked at using federal money to pay for what oftentimes were local projects entirely within a state (such as the Maysville Road, in Kentucky) or which seemed to benefit one section more than another. Industrial Workers Lowell Girls: Farm girls who worked in the textile mills in Lowell. Girls were preferred as workers because the company did not have to pay them as much as men and because they tended to be more docile, controllable laborers. The Merrimack Manufacturing Co. created what it hoped would be a model industrial town, known as the Lowell system. Next to the water-powered mill, it built dormitories to provide safe and comfortable housing for workers; kitchens for regular prepared meals; and lecture halls and libraries for worship, education, and cultural events, and all in a park-like setting along the Merrimack River. Although conditions were very good at first, by the mid-1830s, age had eroded much of the town pleasant appeal and an economic depression caused the company to cut wages and services. By 1840, the thirty-two mills and factories in Lowell turned the town into a commonplace grimy industrial town. Craft Workers’ Manifesto (1827): Declaration by skilled mechanics of Philadelphia, complaining about poor working conditions and low wages; it condemns businesses that put profit ahead of the welfare of workers; and calls on mechanics to unite to force businesses to improve working conditions. Recalling Jefferson’s arguments against the “slavery” of the workshop, it declares, “all who toil have a natural and unalienable right to reap the fruits of their own industry.” Commonwealth of Massachusetts v. Hunt (1842): Massachusetts Supreme Court case involving the legality of trade unionism. To combat poor working conditions, dropping wages, and job insecurity, many craftsmen or skilled workers formed trade unions. The most significant of them were the Mechanics’ Union of Trade Associations, which included carpenters, shoemakers, bricklayers, and others; and the National Trades’ Union. Businesses obviously opposed the unions, accusing them of being “combinations” or monopolies designed to raise the price of labor. In Commonwealth v. Hunt, the state court ruled that forming a union was legal and the union could demand that only union members be hired. It represented a small step toward empowering workers. “The Corrupt Bargain”: An alleged deal between Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams in the disputed 1824 election. With four candidates for POTUS (including William Crawford) Andrew Jackson took the most votes, but did not win a majority in the Electoral College. The election was thrown to the House, which voted for Adams. Supporters of Jackson believed Clay agreed to support Adams in return being named Secretary of State. Both men denied the charge (and Adams in particular was a man of high honor) and no evidence exists to prove it occurred, but it created deep animosity between Clay and Jackson and started what has been called the Era of Hard Feelings. CANDIDATES FOR THE 1828 PRESIDENCY JOHN QUINCY ADAMS • Reputation as the greatest secretary of state in the nation’s brief history. • Reputation as being highly intelligent and hardworking. • Called Jackson “incompetent both by his ignorance and by the fury of his passions.” ANDREW JACKSON • Reputation as a hero at the Battle of New Orleans. • Fiery personality earned him the nickname “Old Hickory” after a tough, hard wood found on the frontier. • Portrayed himself as a common man’s candidate. • Attacked Adams as an out-of-touch aristocrat. Jacksonian Democracy Universal White Male Suffrage: During the 1820s, states across the nation began eliminating property restrictions on voting. In the 1828 election, Andrew Jackson, a backwoods South Carolinian born in log cabin, took advantage of the development. He claimed to represent the “common man,” and common men voted for him in droves: he won 56% of the popular vote. Spoils System: Policy initiated by Andrew Jackson of granting government jobs and contracts to political supporters. After the 1828 election, Jackson swept government workers out of office and replaced them with supporters, declaring “to the victor goes the spoils.” He repeatedly removed cabinet members who did not obey his demands, going through five Treasury Secretaries. But he also demanded that the most basic government jobs be filled by supporters. He called the system “rotation in office” and claimed it gave more people an opportunity to benefit from government jobs. Opponents called it the “spoils system.” The spoils system helped build a Democratic Party, as men supported Jackson in return for political patronage. But it politicized minor government jobs and meant that many office holders had no other qualification to work other than being a Jacksonian Democrat. Whig Party: As Jackson removed political opponents from government jobs, two political parties emerged: the Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson and the Whig Party. Two things united Whigs: (1) hatred of Jackson, and (2) like Federalists before them, a belief in a stronger central government and Hamilton’s economic system. Whigs were led by Henry Clay who ran as the party candidate for POTUS twice times but never won. The Whigs gained strength on the national level during the 1840s, notably with Presidents William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor, but internal divisions over the issue of slavery hampered the party’s growth. When Clay and other leaders died, and slavery became a national issue in the early 1850s, the party split and then collapsed. POLITICAL VIEWS OF THE WHIG AND DEMOCRAT PARTIES IN THE MID -1830S WHIGS: • Encouraged industrial and commercial development • Supported creation of a centralized economy • Advocated for expansion of the federal government DEMOCRATS: • Distrusted unchecked business growth • Favored a limited federal government How were the Whigs different from the Democrats? A The Whigs wanted more industry, but the Democrats wanted a centralized economy. B The Whigs distrusted business growth, but the Democrats wanted more commercial development. C The Whigs wanted to expand the federal government, but Democrats wanted to limit it. D The Whigs wanted growth in government, but the Democrats wanted growth in business. Anti-Masonic Party: The first “Third Party” to participate in a presidential election. As male suffrage grew, many newcomers to politics questioned the power of the old political elite. They feared a conspiracy to take power from the people. They focused on the Order of Freemasons, a “secret society” whose members held many high positions in government and business, and whose membership in the past had included most of the important founders of the country, including George Washington. In 1831, New York Masons were accused of murdering a former member who had revealed the order’s secrets. The incident caused tremendous hostility for the fraternity and the Anti-Masons hoped to win elective office on the opposition. They did not win, but they were the first party to hold a nominating convention and to establish a campaign platform. God Favors Our Undertakings Square and Compasses New Order of the Ages Indian Removal Act: After settlers pushed into Indian lands, causing conflict, Congress approved President Jackson’s plan to move Indians to the “Great American Desert” west of Arkansas. Many tribes fought removal. In Illinois, militia slaughtered the Sauk and Fox Indians in “Black Hawk’s War.” In Florida, Seminoles fought in Osceola’s War and were all but wiped out. Those who lived were removed to the Indian Territory. Trail of Tears: Gold was discovered on Cherokee land and whites wanted access to it, but the Cherokee refused to yield. They went to court to fight a Georgia law that brought the Cherokee under state control. In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Supreme Court ruled the law unconstitutional because the Cherokee were a treaty nation and under federal jurisdiction. President Andrew Jackson, however, refused to enforce the court’s ruling (saying, “Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it!”) Instead, Jackson bought the Cherokee land and sold them land in the Indian Territory. The Army led a forced removal from Georgia of the Cherokee in the winter of 1836. Walking 800 miles during winter, more than one-quarter of the Cherokee died. Some hid out in the mountains of North Carolina and eventually received title to federal lands and became the “Eastern Band” of the Cherokees. Nullification Controversy: Tariff Policy in the Age of Jackson I A renewal of the conflict over whether states could nullify federal law as Madison argued in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions (1798). It involved a protective tariff. John C. Calhoun opposed the 1828 tariff, calling it the “Tariff of Abominations” because it forced southern and western farmers to pay more for manufactured items and it made it harder for them to export their farm products. South Carolina insisted it was unconstitutional and refused to collect the tax. Calhoun secretly authored the South Carolina Exposition and Protest in which he offered the “Compact” theory of the Union. Because he was running for Vice-President he did not want his identity as the author known. The issue would continue to fester for five more years. Webster-Hayne Debate: In 1830, the issue of state’s rights grew into an impassioned debate between Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina and Daniel Webster. They debated the question of the nature of the Union. Hayne took up John Calhoun’s statecompact theory, arguing that states could check national power, determining when the national government had gone too far and nullifying federal law. States had the power of “interposition” – the power to protect a citizen of the state from federal government. Webster, a Whig, countered that the Constitution was a contract between the people and government, that sovereignty rested in the people and state and federal governments were their agents. “Liberty and Union,” he proclaimed, “now and forever, one and inseparable.” A majority in the Senate sided with Webster. Nullification Controversy: The Compromise of 1833 Andrew Jackson was viewed as supporting states’ rights because of his criticism of Clay, Adams, and the American System. But he opposed anything that might threaten the U.S. as a nation or his power as President. South Carolina’s continued challenges to the tariff threatened both. At a banquet celebrating Thomas Jefferson in 1830, Jackson was asked to give a toast. Staring Calhoun in the face, he declared, “Our Union— It must be preserved.” Calhoun spilled his drink, then responded saying, “The Union, next to our liberty most dear!” The event was the latest in the on-going political battle of nerves. Jackson over the next year continued to consolidate his power in the presidency, kicking Calhoun’s supporters out of the cabinet. “I consider, then, the power to annul a law in the United States . . . Incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which it was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed. . . . The laws of the United States must be executed.” –Andrew Jackson, 1832 In the 1832 election, the issue of the tariff predominated. South Carolina enacted a nullification law, refusing to collect the tariff. Jackson demanded that Congress empower him to send troops to force South Carolina to collect the tariff. Calhoun resigned the VicePresidency. A new ticket of Jackson and Martin Van Buren was elected in November. Congress passed the Force Bill. But now South Carolina threatened secession. The country was on the verge of civil war. Henry Clay, Jackson’s old nemesis, stepped in to create a compromise that defused the situation. The Compromise of 1833 lowered the tariff rate over time so that it was eventually a revenue tariff. South Carolina agreed with the new tariff, but then called the Force Act null and void. Both sides claimed victory. Jackson said that South Carolina backed down because of the threat of force; South Carolina won a smaller tariff. The Monster Bank The charter of the Second Bank of the U.S. was set to expire in 1836, but in 1832 the bank’s manager, Nicholas Biddle, requested it be renewed early. Bank supporters, including Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, agreed, wanting to renew the charter while they held a majority in Congress. One of the main duties of the bank was to control monetary policy by controlling the amount of hard currency in the economy—too much paper money could lead to inflation. Jackson opposed the bank, believing that it took power away from the states and remembering the trauma caused by the Panic of 1819. Jackson believed that the McCulloch case had been wrongly decided. Many working-class Americans did not trust the bank. Congress passed the renewal bill, but Jackson vetoed it and removed federal deposits from the national bank, putting them in “pet state banks” instead. As a result, a main organizing mechanism of the economy was eliminated, paving the way for rapid chaotic currency expansion from state to state. The inflationary spiral continued to build until 1836 when Clay tried to regain control over currency by forcing banks to exchange paper money for specie – hard currency, through the Specie Circular of 1836. The effort came too late; the economy crashed and America witnessed the Panic of 1837 and subsequent depression. “The Little Magician”: Jackson’s second VicePOTUS, Martin Van Buren, had earned this nickname for being able to manipulate New York politics. Jackson chose not to run in 1836 and picked Van Buren as his successor. Van Buren won the first clear twoparty election since before the War of 1812, representing the party now calling themselves Democrats and defeating three Whig candidates. Although not incompetent, Van Buren is considered only an average POTUS because he had the unfortunate luck of having to govern during the economic depression of the late 1830s and did little to turn the economy around. Van Buren was renominated by the Democrats in 1840, but lost the election. Panic of 1837: Amid the monetary crisis in America, depression in England spilled over to the U.S. in 1837. England stopped buying American cotton. The price of cotton dropped, breaking the southern economy. English investment in northern industries and railroads dried up. A poor wheat crop broke western farmers. Creditors foreclosed on farms. Banks failed. Prices crashed. Businesses panicked, throwing thousands out of work – unemployment approached 35%. Without government welfare, the jobless had to turn to churches and voluntary societies for help. The Van Buren administration responded by holding back tax rebates to the people and by printing paper money to cover immediate expenses. The economic distress opened the door for Whigs to end the Jacksonians’ hold on the presidency. Immigration The mid-1800s saw a spike in immigration, particularly from Ireland and southern Germany. Between 1830 and 1860, nearly 5 million people immigrated to the U.S., almost half of them during the decade, 1845-1854. The reasons for emigration were numerous and diverse, but for all they included economic opportunity. Most particularly, the Irish (1.6 million immigrants) sought escape from the discrimination of the British and escape from the Potato Famine that killed a million Irish poor, starting in 1845. Like the Irish, the southern Germans tended to be Catholic. Unlike the Irish, they tended to settle in rural areas. The increase in population and the problems of assimilating the newcomers helped to stoke the reforms of the Second Great Awakening. They also caused backlash against immigrants during hard economic times. Years Immigrants 1820-1829 128,502 1830-1839 538,381 1840-1849 1,427,337 1850-1859 2,814,554 1860-1869 2,081,261 1870-1879 2,742,287 1880-1889 5,248,568 1890-1899 3,694,294 1900-1909 8,202,388 1910-1919 6,347,380 1920-1929 4,295,510 1930-1939 699,375 1940-1949 856,608 1950-1959 2,499,268 1960-1969 3,213,749 1970-1979 4,248,203 1980-1989 6,244,379 1990-1999 9,775,390 Nativism: Anti-immigrant sentiment that arises every time there is a large influx of newcomers. In the 1830s, tension arose as Protestant “natives” thought Catholic immigrants would have divided loyalties with America and the Pope. Nativism increased after the Panic of 1837, as immigrants challenged “natives” for employment and as many immigrants brought European expectations of labor relations to business. Several nativist political groups organized to lobby government to restrict immigration, starting with the Native American Association in 1837. By the late 1840s and early 1850s, they represented a real political movement, with the Order of the Star Spangled Banner and the American Party. The American Party was the most significant. Better known as the Know-Nothing Party because when asked about their organization they were supposed to respond, “I know nothing.” The Know-Nothings won several elections on the local level in 1854. The anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic movement died out as slavery became the political focus in the late 1850s. Cultural and Social Reform, 1820-1850 2.05 Identify the major reform movements and evaluate their effectiveness 2.06 Evaluate the role of religion in the debate over slavery and other social movements and issues Hudson River School: Group of landscape painters working in upstate New York during the 1830s and 40s. Their work represented a new American Romanticism, emphasizing the beauty of the region and the huge scale of the natural world compared to the relative smallness of humans. Some borrow from the Neo-Classical style of Europe, showing Greek- or Roman-style structures in a pastoral surrounding. But most of the work is uniquely American. Second Great Awakening: Religious revival movement. It began in New England and up-state New York (Burnt-Over District) and spread west. Its greatest proponent was Charles Grandison Finney, who preached an extremely emotional approach to God, saying that the spirit went through him “in waves and waves of liquid love.” Like its predecessor in the 1740s, the second revival was caused by a belief that the nation was becoming too materialistic and not being “a city upon a hill.” Some reforms had heavy nativist overtones, however, as Protestant middle-class women fretted over assimilating poor Irish immigrants. The revival led to the creation of several new churches [Shakers, Jehovah's Witness, Seventh Day Adventist, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (the Mormons)]. It also led to many social reform movements, including: temperance (Lyman Beecher), public education (Horace Mann), prison reform (Dorothea Dix), women's rights, and abolitionism. But abolitionism was the most significant reform movement spurred by the Second Great Awakening. The millennial spirit at the core of the revival and the eradication of sin that it demanded merged with practical political and economic concerns as America grew into new territories west of the Mississippi to propel the country toward an inevitable final conflict over freedom and slavery. It led to the “Great American Schism.” Temperance: Reform movement that attacked alcohol use, which was so excessive in the U.S. that one historian called America, “the Alcoholic Republic.” Several voluntary societies organized to coerce men to pledge not to drink. When moral suasion failed, temperance organizations, such as the American Temperance Society and the Washington Temperance Society lobbied state legislatures to enact prohibition laws. Neil Dow effectively prompted Maine to enact such a law (the “Maine Law”) in the 1850s. Transcendentalism: Philosophical and literary movement developing out of (1) (2) (3) European Romanticism: a celebration of an heroic past symbolized by a recollection of classical architecture, a retelling of Arthurian legend, and a closeness to nature Unitarian-Universalism--a belief in the "oneness" of a benevolent God and the essential goodness of man American gnosticism--an individualistic approach to understanding and spirituality. It countered the view of the basic sinfulness of man (thus running in a different direction from the Second Great Awakening) and the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, the Age of Reason. It argued that some things are understood through intuition rather than through science or experience; revelation rather than reason. It originated in 1836 in Concord and Boston, Mass., with the Transcendental Club, which included: Henry David Thoreau, Louisa May Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, and Ralph Waldo Emerson Utopian Societies The Second Great Awakening created many experimental communities across the BurntOver District. Some farming, some industrial, they were based on communalism: all settlers working together for the good of the community. Some were religious, others secular. The Transcendentalists founded Brook Farm where girls, not just boys, got an education and developed beliefs in pacifism. New Harmony, established by Robert Owen in Indiana, was to be a model industrial town owned by the workers but went bankrupt. The Shakers were a religious sect created by Mother Ann Lee in England in the 1770s. They established communal farms in New England, Ohio, and Kentucky based on the equality of women and men. They became best known for building high-quality, yet simply designed furniture, and for musical composition (notably, “Simple Gifts”). The Shakers followed a strict rule of celibacy, growing through adoption of orphans. John Humphrey Noyes founded Oneida in upstate New York with about 200 residents who believed in universal marriage; it was famous for making animal traps and high quality metalwork, especially spoons. Seneca Falls Convention: Meeting the women's suffrage and equal rights movement, held at Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. The movement was led by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The Convention drew up a “Declaration of Sentiments,” stating several demands, including the right to vote and to own property. Although the movement showed considerable support and solid organization, it had unfortunate timing: it failed to achieve its goals because it was drowned out by the slavery issue in the 1850s. ~Declaration of Sentiments~ When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course. We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. Whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and, accordingly, all experience hath shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they were accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their duty to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of the women under this government, and such is now the necessity which constrains them to demand the equal station to which they are entitled. . .