Chapter F8

advertisement

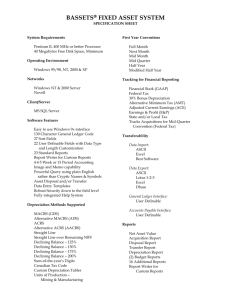

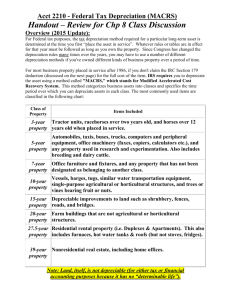

CHAPTER F8 Challenging Issues Under Accrual Accounting: Long-lived Depreciable Assets – A Closer Look © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 1 Learning Objective 1: Explain the process of depreciating long-lived assets as it pertains to accrual accounting. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 2 Depreciation Recall the basic definition of depreciation (from Chapter 6): Depreciation is: a systematic and rational allocation of the cost of a long-lived item from asset to expense. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 3 Depreciation Over time, the cost of using the asset is transferred to the income statement as an expense. As the cost of the asset is transferred to the income statement, the historical cost on the balance sheet is reduced by the accumulated depreciation. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 4 Learning Objective 2: Determine depreciation expense amounts using both straight-line and doubledeclining-balance depreciation methods. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 5 Effect of Estimates Estimated useful life of the asset and the estimated disposal value at the end of that useful life each play a large role in determining the amount of depreciation to be recognized in each year that we use the long-lived asset. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 6 Discussion Questions Think about your most recent purchase of a long-lived asset. Maybe you bought a computer, a car, or a TV. How long do you expect to keep it and use it? What do you think it will be worth when you are through with it? How certain are you of these answers? © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 7 Effect of Estimates Example: Assume that we buy a new $6,000 computer system. We are unsure whether to use a three-year life or a five-year life, and some of our “experts” think that it could be worth as little as $0 after three years or as much as $1,000 after five years. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 8 Effect of Estimates Depr. Year Expense 1 2 3 4 5 1,000 1,000 1,000 1,000 1,000 Book Value 5,000 4,000 3,000 2,000 1,000 Using 5 years and $1,000 disposal value, you depreciate $1,000 each year. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing Year 1 2 3 Depr. Book Expense Value 2,000 2,000 2,000 4,000 2,000 0 Using 3 years and $0 disposal value, you would depreciate $2,000 each year. 9 Effect of Different Methods When preparing the depreciation schedule for a newly purchased long-lived asset, an accountant has a choice of several different depreciation methods. By choosing one method over another, the accountant has an impact on the amount of expense that will be reported in any given year, and, therefore, also the net income. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 10 Straight-line Depreciation In Chapter 6, the straight-line method of depreciation was illustrated. It is probably the easiest method, and it is definitely the most heavily used method in the U.S.A. Approximately 95% of major corporations in America use straight-line for some or all of their long-lived assets. 11 Straight-line Alternatives The straight-line method could be calculated on the basis of time, with an equal amount of depreciation being allocated to each time period. Alternatively, the straight-line measure could be units of production or some other measure of usage, such as miles driven for a vehicle or hours flown for an airplane. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 12 Straight-line Based on Time The basic premise is that the same amount of depreciation will be recognized in each year of the useful life of a long-lived asset. The computer system (5-year or 3-year) depreciation schedules given previously are examples of the straightline method based on the passage of time. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 13 Straight-line Based on Usage The other variation of the straight-line method is often called the production depreciation method. Instead of estimating the number of years of useful life, we will instead estimate the amount of usage that we expect from the asset. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 14 Production Depreciation Method Assume that a pizza parlor buys a delivery truck. Rather than drive the truck into the ground, they decide that they should sell it after it has 75,000 miles on it. The original cost is $20,000 and they estimate that the disposal value will be $5,000 at that time. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 15 Production Depreciation Method Step One: Calculate the depreciation charge per mile driven: Depreciable Base $15,000 Estimated Miles 75,000 = $.20/mile Step Two: Calculate depreciation each year (or interim period) by multiplying actual miles driven by the per mile depreciation: Year 1: 30,000 miles X $.20 = $6,000 © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 16 Effect of Different Methods Several other depreciation methods are considered acceptable and are used by some companies. Most of these other methods are called accelerated depreciation methods. They are accelerated in that a larger amount of expense is taken in the early years, and less in later years. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 17 Double-Declining-Balance Method The most heavily used accelerated method is the double-declining-balance method. The main features of this method are: (1) it depreciates at a rate (%) equal to double the straight-line rate, and (2) you do not consider the estimated disposal value during the early years of depreciation. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 18 Double-Declining-Balance Method First step: determine the DDB rate. The DDB rate is equal to twice the annual straight-line rate. For a five-year asset, the annual straight-line rate is 1/5 or 20%. The DDB rate is 40%. For an three-year asset, the annual straightline rate is 1/3 or 33.3%. The DDB rate is 66.7%. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 19 Double-Declining-Balance Method Second step: Multiply the DDB rate by the book value at the beginning of the year. You will use the same rate (%) each year, however, the amount of depreciation will decrease each year because the beginning book value also decreases each year. NOTE: Be careful in the later years, don’t depreciate the asset below salvage value. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 20 Double-Declining-Balance Method Let’s prepare double-declining-balance depreciation schedules for the computer system mentioned in an earlier slide. First, let’s assume a five-year life with $1,000 disposal value, and Second, let’s assume a three-year life with a $0 disposal value. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 21 DDB Schedule, 5-Year Asset Year Begin Book Value 40% Depr. Expense Ending Book Value 1 2 3 4 5 6,000 3,600 2,160 1,296 1,000 2,400 1,440 864 296 0 3,600 2,160 1,296 1,000 1,000 Due to the accelerated amount of depreciation, the asset is fully depreciated after four years. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 22 DDB Schedule, 3-Year Asset Year Begin Book Value 66.7% Depr. Expense Ending Book Value 1 2 3 6,000 2,000 667 4,000 1,333 667 2,000 667 0 Using the 3-year life with zero disposal value, the amount of depreciation for year 3 is equal to whatever amount remains. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 23 Learning Objective 3: Describe in your own words the effects on the income statement and balance sheet of using different methods of depreciation. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 24 Understanding the Effects The choice of straight-line or an accelerated method affects all of the following: Depreciation expense in each year. Net income in each year (because of #1). Accumulated depreciation in each year (except the last year when fully depreciated). Net book value in each year (because of #3, except the last year again). © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 25 Understanding the Effects However, the choice of method does NOT affect the following: The amount of depreciation taken over the entire useful life. The amount of net income reported over the entire useful life. The book value at the end of the useful life of the asset. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 26 Learning Objective 4: Compare gains and losses to revenues and expenses. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 27 Disposal of Assets At some point, a business will decide to dispose of a long-lived asset. This could happen at the end of the estimated useful life, or it could just as easily happen sooner or later than we originally estimated. Each time we dispose of an asset, we need to determine whether there is a gain or loss on disposal. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 28 Gains and Losses A gain is a net inflow resulting from a peripheral activity of the company, such as selling a long-lived asset for an amount greater than its net book value. A loss is a net outflow resulting from a peripheral activity of the company, such as selling a long-lived asset for an amount less than its net book value. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 29 Gains and Losses Gains and losses are important accounting elements. They are reported on the income statement along with revenues and expenses. Thus, the income statement equation is now expanded to: Net income = Revenue + Gains - Expenses - Losses © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 30 Learning Objective 5: Calculate a gain or loss on the disposal of a longlived depreciable asset. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 31 Determining Gains & Losses Consider these various examples of the disposal of a depreciable asset: 1. A fully depreciated delivery truck (with 220,000 miles on it) is hauled off to the junk yard. 2. A delivery van with a net book value of $8,000 is traded in on a company car for the sales staff. 3. A one-year-old rental car with a net book value of $15,000 is sold at auction to a car dealership. Let’s explore this third example further. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 32 Calculating Gain on Disposal A gain on disposal of a depreciable asset will occur when the asset is sold for an amount in excess of the ending book value. Example: The Car Rental Company sells a one- year-old car to a car dealership. The company has depreciated the asset to a book value of $15,000. The dealership pays $16,500 to buy the car. The Car Rental Company records a gain on disposal of $1,500. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 33 Calculating Loss on Disposal A loss on disposal of a depreciable asset will occur when the asset is sold for an amount less than the ending book value. Example: The same situation with the Car Rental Company selling a car (book value of $15,000) to a dealership. The car dealership pays $14,500 to buy the car. The Car Rental Company records a loss on disposal of $500. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 34 Disposal with No Gain or Loss There will be no gain or loss on the disposal of a depreciable asset when the asset is sold (or traded) for an amount equal to the recorded book value. Example: The same situation with the Car Rental Company selling a car (book value of $15,000) to a dealership. The car dealership pays $15,000 to buy the car. No gain or loss. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 35 Learning Objective 6: Explain the effects on a company’s financial statements when management disposes of a depreciable asset. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 36 Effects of an Asset Disposal on the Balance Sheet The book value of the asset will be removed from the balance sheet and decrease both the asset account and accumulated depreciation account. Cash will increase by the amount received for the asset. If cash exceeds book value, equity will increase by the amount of the gain. If book value exceeds the cash, equity will decrease by the amount of the loss. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 37 Effects of an Asset Disposal on the Income Statement A gain on the disposal will increase net income. A loss on the disposal will decrease net income. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 38 Learning Objective 7: Draw appropriate conclusions when presented with gains or losses on an income statement. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 39 True Meaning of Gains/Losses Net book value is the end result of the depreciation amounts charged against an asset. Therefore, if book value does not equal the disposal value of an asset, we simply took too much or too little depreciation for the asset. The gain or loss is just a depreciation adjustment at the end of the process. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 40 True Meaning of Gains/Losses Case #1: You bought an asset at a cost of $9,000. You have been depreciating this asset at a straight-line rate of $1,000 per year for 4 years. The net book value at this time is $5,000 and you sell it for $4,000. You will record a loss on sale of $1,000. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 41 True Meaning of Gains/Losses Case #2: Same asset, $9,000 original cost and depreciated for the past four years. If you had depreciated $1,250 each year (total of $5,000), the book value would have been equal to $4,000. When the asset was sold for $4,000, there would be no gain or loss. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 42 True Meaning of Gains/Losses In case #1, you have $4,000 depreciation and a $1,000 loss on sale. This reduces net income by $5,000 over the life of the asset. In case #2, you have $5,000 depreciation and no gain or loss on sale. Again, net income has been reduced by $5,000. Either way, total net income is the same over the life of the asset. © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 43 End of Chapter 8 © 2007 Pearson Custom Publishing 44