Women Reflected in Art of the Renaissance

advertisement

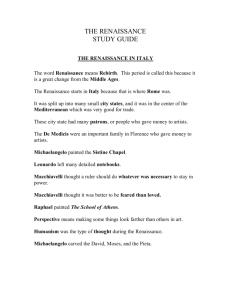

Zimmerman 0 Women Reflected in Art of the Renaissance Emma Zimmerman Zimmerman 1 Emma Zimmerman English 1020 July 22, 2015 Artwork from the Italian Renaissance is well known all over the world, almost everyone learns about pieces like the Mona Lisa by Leonard da Vinci or Michelangelo’s David. These artists have become a part of our pop culture, for example the names of the Ninja Turtles, and are referenced to in everyday conversations for their discoveries and their innovative thinking. These Renaissance Men’s names and artwork will live forever in history as great accomplishments, and most likely never be surpassed, but what does their art actually say about their time? What have these artist left us to gush over? What clues have these men left in their creations for students of the arts, historians, or even women to draw conclusions about what life was like during this time period? How and why are women depicted in the Renaissance? Artwork reflects themes of a society, the cultural norm, but art can also be used to push those limitations and challenge its viewers. Women depicted in art from the Renaissance have both pushed the cultural norms of the fifteenth century as well as defined their evident and limiting gender roles. As an art student I have been introduced to many of these great pieces and also been in awe of their magnificence, but as a woman I have to ask what are these amazing pieces reflecting about women? As it turns out I am not alone in asking about women’s role and how it is depicted during this amazing period of time. During the feminist movement in the 1970s many women began to ask what about ‘her-story’ and this was followed with many responses to giving the women throughout history a voice. In my research I have been overwhelmed with the amount of text as I searched for gender roles depicted in artwork from the Zimmerman 2 Italian Renaissance, and after reading many interpretations of various pieces I think I have collected an interesting perspective of how history, art, and women’s studies have collided during this moment in time. The female form, or lacking female presence, depicted in art from the late Medieval and early Renaissance in Europe reveals the morals and gender roles that women were held to during this time. From the influence of religion and the forever Eve found in all women to the unobtainable virtues of Mary, the objectification of women and the male gaze, and the roles women were confined by, all can be seen in the artwork. By taking a different approach at analyzing these marveled works of art and artists I hope to reveal a different perspective of the Renaissance, the perspective of the oppressed gender, women. The late medieval period in Italy looked much different than other parts of Europe, Italy was gaining wealth in the merchant class and beginning to grow as trade became more efficient, and along with the invention of the printing press and the use of common vernacular were utilized; art was able to take on a new purpose. Before this unusual period, artwork was typically associated with the Church, depictions of the Bible were created to aid the illiterate in understanding the teachings of the faith. Most art reflected themes of stories from the Bible, like Adam and Eve. “From the beginning, the image of woman was created by man in the Christian Middle Ages, this was the image of Eve” (Grössinger, 1). This opening statement from Picturing Women in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art sets the tone for my research, women’s image in the eyes of men. With this realization a new perspective of art was taken on, more questions developed for me, who was the intended audience for this art? Flipping through history books the images of Saints and biblical characters developed with greater symbolism and iconography ultimately leading to the rediscovery of naturalism from the classical antiquity. This was the rediscovery and new found appreciation for the human form. Rather than the focus of society Zimmerman 3 directed outward, it was redirected inward. Fueled by a profound since of mortality after the Black Plague, the Renaissance ignited. Art work began to capture the human body and the study of our own identity and experiences. As art continued to develop so did the subject matter; Virgin Mary’s one ample bosom and the nudity of Eve became more common, even celebrated as well as ridiculed. The wealth of the middle class allowed for funding of the arts, commissions for portraits popularized. Women other than Mary and Eve began to be seen in art, but still limitations and gender roles are prevalent themes of nobility’s profile portraits of women (Simons, 41). While the portraits of men began to explore three quarter profiles and reflect the subject’s class, wealth, and power, women were documented as objects and the portrait acted as a contract or documentation of marriage. Nobles and rulers’ images have been seen because of the portraits painted during their lifetime, similar to how photographs are used today. Typically they are depicted sitting and either engaged with their work or a hobby, but in Patricia Simons piece; “Women in Frames: the gaze, the eye, the profile in Renaissance portraiture”, these images are compared to those images of women from the same time. For the women in these portraits there is very little documented about them as individuals, but rather objects, objects to be gazed upon, object that were traded to strengthen men’s power. The rediscovery of Roman and Greek literature surfaced writings from Aristotle and Plato, humanism continued to change the climate of the times. This new interest in the human form and emotion, as well as the study of science and nature is reflected in the arts, and allowed new families of wealth to commission pieces that combined both theology and Christian morals, this is where some of the great artist we still know today began to surface. Botticelli’s Primavera is evidence of this occurrence of new found thought and curiosity of the Roman and Greek Zimmerman 4 cultures. With this resurgence the nude female figure became more acceptable, seen in Botticelli’s Birth of the Virgin, until this piece the female nude had been tabooed by the Church. The acknowledgement of female sexuality would only empower the temptress found in all women, the forever Eve. Leonardo da Vinci was unlike other artists, his depiction of women allowed them a humanization in art that had not been render before, through his portraits of real women he broke the profile that women had been restricted by and gave the gender depths (Garrard, 60). Not only did Leonardo da Vinci humanize women, but also began to retie the elements of nature and womanhood, he studied the cycle of life and birth, his sketches lead to the anatomy of the female body, challenging the preface concept that the female body was inferior to male. Mary Garrard argues da Vinci’s intrigue in the sciences of reproduction began to educate the public and empower women in “Leonardo da Vinci: Female Portraits, Female Nature.” Titian was famous for his depictions of the nude female figure; there is much controversy weather he was objectifying the female form or if he was celebrating female sexuality. These artists and their pieces all are representations of gender in the Renaissance culture and how women were oppressed in this patriarchal society, also it is important to take notice that all of these artists were men. Women in religious art is used to help enforce the roles of women, how she should conduct herself. Prior to the Renaissance, most artwork was commissioned by churches for churches. The Virgin Mary was a popular character to be immortalized in art, as the ultimate woman, the second coming of Eve. The virtues of Mary were well known and symbolism often helped to reiterate these morals that women of the masses should strive for, chastity and virtue, submissive and passive, and to remember her purpose of motherhood. The forever virgin is often shown as a young woman, always covered, with the exception of one breast that nurtures her Zimmerman 5 son, the savior. While nudity was not common in the Middle Ages, this one bare breast was allowed, as it was an indication, or instruction manual for women and what their job was, to reproduce (Miles). While these elements are clearly contradicting it is hard to relate to a virgin mother, but better this than Eve, the sinner who damned all of humanity. Thus begins the outlines of gender roles in society, the iconography and direct messages to women; strive for: chastity, motherhood, and of servitude. This is how the dehumanization of women was taught and where the oppression grew its strength, through this concept that all women carried the sin of man and every single woman was to blame for all suffering, because she steamed from Eve. These medieval morals for women are not only translated in the art, but also in documentations of the time, for example in Brucker’s Giovanni and Lusanna: Love and Marriage in Renaissance Florence a clear construct of what and how a women should conduct herself as a wife and widower (Brucker). Most art of women has aspects leading to virtues or the clear message to restrain one’s cardinal desires and not to give into the evil women’s seductive attributes. Female sexuality should be smothered, for that is where she draws her power from, this concept is often a theme in art (Moulton). As women’s lives were documented more and more the large throughout history with merit through motherhood or marriage the number of portraits that emerged in the early Renaissance are important to take note of because of their direct correlation with gender roles of this period. These depictions of women in the upper classes are not as they seem, reflections of women adorned with beautiful objects and clothing, youthful and attractive, stuck in profile as the viewer’s eyes devour the images’ subject matter. The purpose of this type of art was to document one’s marriage. The subject is typically wearing their wedding dress and jewelry that was a part of their dowry, this is a peek into the concept of marriage during this time, an Zimmerman 6 exchange of items. An example of this type of portraiture is Domenico Ghirlandario, Giovanna Tornabuoni, 1488, a new bride decorated in jewelry and a wedding dress, seated staring away to the light (Simons, 27). While the way the women are dressed and what objects they have with them are an easy tell of class, take into account the side profile. This positioning of the female figure is a clear representation of the gender roles and cultural norms. Eye contact is even avoided in a painting. During this era women were taught to gaze downward, eye contact was considered seductive and promiscuous. Brucker makes reference to this in the documentation of Giovanni and Lusanna on page 27, Lusanna was accused of staring at men with whom she interacted and how this was an indication of her promiscuity. In Patricia Simon’s essay Women in Frames: The Gaze, The Eye, and The Profile in Renaissance Portraiture she states women’s “optic engagements” were prohibited for Noble women. Simons goes on to explain how women whom are depicted in these paintings are often nothing more than passionless objects (Simons, 51). The dehumanization occurs in order to continue the suppression of women’s ‘power’ over men, by means of seduction. Simons also makes the argument that these images were not created for women, but for men and by men (Simons, 41). These images were literal documentation of a business transaction as a women followed their societal duty of succession from daughter to wife. The Renaissance was a rebirth for both art and culture, as society was changed by the development of humanism. The study of man became the focus, rather than God. The human form and what it was capable of became a common subject for the art world. As sculptures carved versions of David, from the biblical story David and Goliath, the male nude was further explored, accepted, and even celebrated. Art allowed a place for the theological stories from the Greek and Roman cultures to collaborate with well-known Bible stories while promoting the Zimmerman 7 ideals and virtues, such as civic duty. David by Michelangelo compared to the previous version by Donatello or even the later version by Bernini provide a strong example of gender roles; specifically the portrayal of men in society. The protector, leader, the thinker, and overall slayer, mankind and masculinity were celebrated (Kelly-Gabol). The reintroduction of the theological tales were accompanied with new and more female characters as well as male. There were no longer just an Eve and Mary. Powerful families began to commission artists to construct Neoplatonist concepts with a theological cast, the Medici family is probably the most famous for their patronage of the arts. Sandro Botticelli was commissioned by Lorenzo the Magnificent of the Medici family to paint the famous Primavera that is just that, a collision of religious ideologies executed with theological cast (Zirpolo). Venus seems to be merged into the Christian version of Mary as she is centered in the larger piece and surrounded by nature and possibly the coming of spring (Garrard, 72). Primavera is argued to have been a representation of a brides’ conduct, and a documentation of a marriage in the Medici family (Zirpolo). Zirpolo states the iconography of the three Graces are direct representations of chastity and virtues, which all brides should maintain. She also explains that the overall demeanor of the Graces is what one expects in a wife and good Renaissance women, as well as the calm stoic faces that do not show emotions (Zirpolo, 101-102). Gender roles are the underlying theme for this piece as well. This piece closely relates to Botticelli other famous piece the Birth of Venus, this piece features a nude Venus emerging from a seashell as she is blown in on the sea foam. Female nudes had not been explored during this time, with the exception of Eve or the Virgin Mary’s breast, unlike the male figure which was already being celebrated, Michelangelo’s David. If this piece had emerged any earlier the Church may have obtained more power and Zimmerman 8 could have saw to its’ destruction and the danger to its creator, but being commissioned by the powerful Medici family, no questions were asked, and the female nude was reintroduced into the Europe since the Antiquity. Leonardo da Vinci is not an unknown name in the modern day, he is responsible for more than just is most popular piece of art, the Mona Lisa, he was the first to break female portraits from the side profile into the three-quarter profile pose in Italy, and gave women a responding look (Garrard, 60). This was much different from the earlier portraitures that limited women to a passive and vulnerable pose. Da Vinci included elaborate backgrounds that encompassed detailed natural settings, this backgrounds reflect da Vinci’s tie of women to nature, and the cycle of birth (Garrard). Aristotle’s Generation of Animals was the explication to the mystery of reproduction, claiming that women did not provided any essence to creating life, just passive matter, da Vinci begins to question this notion (Garrard, 70). Leonardo’s sketches of the fetus provide the world with a better insight to the reproduction process. Da Vinci’s thoughts surround women and the empowerment he provided them was challenged by various observes, questioning Leonardo’s sexuality. “The eye is to be the window of the soul” –Leonardo da Vinci, with his remarkable portraitures he was able to humanize women and alter the limitations of the art realm (Garrard, 61). Women became a more interesting subject matter as the nude became publically accepted in the art world. Many different renditions of the female form developed and the ideas of chastity were endangered. The need for female models was a difficult problem. Many artists used prostitutes. This is important to keep in mind, seeing as that just because there were female nudes as subject matter did not mean women were empowered by being naked, rather seen as a source of pleasure (Lyons and Koloski-Ostrow). Titian is an artist well known for his female nudes, one Zimmerman 9 in particular Sacred and Profane Love, 1514. This piece was commissioned by a wife for her husband, it is an image of her dressed in a beautiful wedding dress, covering the majority of her body, and another image of her in the nude. The wife was a widow from a previous marriage, thus her virginity was obviously no longer intact, it is thought that this piece is challenging this notion, as well as the idea of women in private versus public realms (Goffen). Titian’s woman, similar to da Vinci, obtains an interactive look between the viewer and the clothed figure, she is not ashamed of her nudity, but rather enjoying it as she looks at the clothed version of herself, and the dressed figure looks at the viewer. There is a strange play since of perspective as the woman watches the viewer watch the nude version of herself. Titian is challenging the society’s issue with female nudity as well as the female sexuality. Was Titian’s intentions to provide the female figure with a sense of sexuality and allow his figures to obtain power, or to merely depict the pleasing female form for other men to enjoy? Intentional or not there is a clear sense of power or ownership in the eyes of these female figures. After looking at some specific artists and pieces that were popular topics for discussion in concept of gender roles depicted through art, it is interesting to reflect and realize all of the artists were men. I have come across a few female artist from this era with interesting stories, but none can compare to the popularity of some of the artists previously discussed. Flipping through history books and notes from women’s studies I have remembered that many of this artists were commissioned by guilds that were created by women who had become widows. Leonardo da Vinci worked for many women. The women of the Renaissance ultimately didn’t have a much of a rebirth, their virtues and cultural expectations remained similar during this time, the sexuality was suppressed as well as their female form neither celebrated nor studied at the same level as the male figure (Kelly-Gadol). Zimmerman 10 The objective of my essay was to dig into the gender roles of the Renaissance and how they were reflected in the art work that emerged from this era. I wanted to know what role women played in the artwork, what was the purpose of this new inventive art and what was it saying about this time period. By taking a closer look at the artists and some of their collections rather than particular pieces aided my discovery that the purpose of women in Renaissance art was to reflect the virtues of the time period, immortalize how women should conduct themselves in the eyes of men and religion. Depending on the patronage changed the subject of the piece, but the overall virtues and values of the periods would ultimately be perceived. I think this is true for any culture, the art created is supposed to preserve what the ideals of that society are, but in this case it was the ideals men had for women, rather than women having ideals for themselves. Zimmerman 11 Works Cited Brown, Shelby. ""Ways of Seeing" Women in Antiquity: An Introduction to Feminism in Classical Archaeology and Ancient Art History." In Naked Truths: Women, sexuality, and gender in classical art and archaeology, by Claire L. Lyons and Ann Olga KoloskiOstrow, 12-42. New York, NY: Routledge .1997. Print. Brucker, Gene. Giovanni and Lusanna: Love and Marriage in Renaissance Florence. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.1986. Print. Garrard, Mary D. "Leonardo Da Vinci: Female Portraits, Female Nature." In The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, 59-85. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.1992. Print. Gilboa, Anat. New Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Gender in Art. Accessed November 17, 2014. <a href="http://science.jrank.org/pages/9459/Gender-in-Art-RenaissanceBaroque.html">Gender in Art - The Renaissance And The Baroque</a>.2005. Web. Goffen, Rona. "Titian's Sacred and Profane Love and Marriage ." In The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, 111-126. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. 1992. Print. Grössinger, Christa. Picturing Women in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art. Manchester: Manchester University Press.1997. Print. Kelly-Gadol, Joan. "Did Women Have a Renaissance?" In Becoming Visible: Women in European History, by Renate Bridenthal and Claudia Koonz. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1977. Print. Zimmerman 12 Lyons, Claire L., and Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow."Naked Truth About Classical Art: An Introduction." In Naked Truths: Women, sexuality, and gender in classical art and archaeology, by Claire L. Lyons and Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, 1-11. New York, NY: Routledge. 1997. Print. Miles, Marget R. "The VIrgin's One Bare Breast: Nudity, Gender, and Religious Meaning in Tuscan Early Renaissance Culture." In The Expanding Discouse: Feminism and Art HIstory, by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, 27-38. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. 1992. Print. Moulton, Susan."Venus Envy: A Sexual Epistemology." ReVision 42. 1999. Print. Russell, H. Diane. Eva/ Ave: Women in Renaissance and Baroque Prints. New York, NY: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York. 1990. Print. Simons, Particia. "Women in Frames: The Gaze, the Eye, the Profile in Renaissance Portraiture." In The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, 39-58. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. 1992. Print. Zirpolo, Lilian. "Botticelli's Primavera: A Lesson for the Bride." In The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, 101-110. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. 1992.Print.