Perspectives on Best Practices for Managing Acute

advertisement

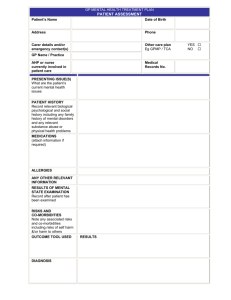

Perspectives on Best Practices for Managing Acute Relapses in Multiple Sclerosis Moderator Barry G. Arnason, MD Professor of Neurology University of Chicago Staff Physician Department of Neurology University of Chicago Hospitals and Clinics Chicago, Illinois Panelists Kathleen Costello, RN, MS, CRNP, MSCN Assistant Professor Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Nurse Practitioner Johns Hopkins Hospital Baltimore, Maryland Saud A. Sadiq, MD Director and Senior Research Scientist Tisch Multiple Sclerosis Research Center of New York Director International Multiple Sclerosis Management Practice New York, New York Disclaimer This program will include discussion of treatment options that may deviate from FDA recommendations. Program Goals • Discuss therapeutic options available to manage acute relapses in patients with MS • Individualize therapy for acute relapse in MS • Develop strategies for managing suboptimal response to acute relapse treatment and addressing patient tolerability issues Overview • Challenge of MS relapse • Underlying pathophysiology • Strategies for managing relapse Definition of Relapse In clinical trials: • Neurological deficit lasting > 24-48 hours • With or without change in EDSS score In the clinic: • • • • • Change from baseline Sustained for a period of time (hours, days) Otherwise unexplained by other medical conditions Relapse is not usually a medical emergency Symptoms may resolve over time Vollmer T. J Neurol Sci. 2007;256:S5-S13.[1] Relapse Triggers and Associated Conditions: Cause or Effect? Infectiona • Fever can worsen MS symptoms • Demyelinated nerves are sensitive to temperature changes • Infection can precipitate MS attacks Other conditions (pseudorelapse) • • • • • • Depression Stress Sleep issues Fatigue Heat intolerance Headachesb a. Vollmer T. J Neurol Sci. 2007;256:S5-S13.[1] b. Mohrke J, et al. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69570.[2] Patient Assessment • Response to relapse is highly individualized • Symptoms may resolve on their own (pseudorelapse) • Encourage patients to call to discuss the situation • Take a careful history − MRI may not be necessary • Consider bringing patient in for clinical evaluation (especially if motor symptoms are involved) • In spinal cord disease, MRI is not likely to be negative Relapse Treatment: Paradigm Treatment may be indicated if: • Patient reports new neurological symptoms and change in function affecting quality of life − Sensory, cognitive, mood, or motor • Associated medical conditions have been ruled out • MRI shows Gd-enhancing lesion(s) Acute relapse is not likely present if during routine evaluation, MRI in an asymptomatic patient shows new lesion(s) or a Gd-enhancing lesion since last MRI • In such cases, consider changing DMT Myhr KM, et al. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2009;73-80.[4] Relapse Treatment: Steroids Steroids: first-line treatmenta,b • Standard regimen = 1 g/d for 3-5 days − Treatment for other autoimmune diseases usually involves lower doses (eg, 5-40 mg/d for RA) Steroid mechanismc • At low doses, steroids regulate gene activity • At high doses, steroids affect cell membranes (ie, not underlying disease mechanisms) a. Burton JM, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD006921.[3] b. Myhr KM, et al. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2009;73-80.[4] c. Arnason BG, et al. Mult Scler. 2013;130-136.[11] Relapse Treatment: Approaches Dr Sadiq • For most patients with relapse: − 1 g/d IVMP x 3 days for most patients with relapse − Oral taper not necessary • If motor symptoms present, consider: − 5 days − Oral taper (usually rapid, 2-3 weeks) • Address steroid adverse effects, eg: − Sleep issues − Gastrointestinal upset Relapse Treatment: Approaches (cont) Ms Costello • High-dose oral prednisone (eg, 1250 mg) an option − Good efficacy; minimal adverse effectsa − Some patients experience sleeplessness, may not feel as well • IV steroids − Protocol at Johns Hopkins = IVMP 1 g/d x 5 days or oral equivalent − Chart review (N = 50) did not identify a difference in outcomes with 5 days vs 3 daysb a. Morrow SA, et al. Can J Neurol Sci. 2012;39:352-354.[5] b. K. Costello, written communication, September 2013. Steroid Treatment: Risks and Benefits • Variable patient response − Some patients feel energetic; others feel jittery, sleepless • Adverse effects can occur and should be managed − Common AEs: Flushing, acne, dyspepsia, metallic taste − Severe AEs: avascular necrosis, osteoporosis, hypertension, glucose intolerancea-c • Goal: Accelerated recovery; restore function in short term • Steroids per se do not delay disease progressiond… − …But treating acute relapse and optimizing ongoing therapy may affect progression • Frequent use (pulsing) should be avoided − Consider switching DMT a. Sahraian MA, et al. Neurol Sci. 2012;33:1443-1446.[6]; b. Ce P, et al. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:857861.[7] ; c. Ciccone A, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD006264.[8] ; d. Andersson PB, et al. J Neurol Sci. 1998;160:16-25.[9] ACTH • Only FDA-approved drug for managing acute MS attacks • Induces production of glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids • Binds to 5 different melanocortin receptors (1 of which regulates steroids)a,b a. Arnason BG, et al. Mult Scler. 2013;19:130-136.[11]; b. Catania A. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:383-392.[12] ACTH (cont) Option for selected patients • Intolerant to IVMP • History of response to ACTH Drawbacks • Cost, insurance barriers • Adverse effects related to increase in steroids (eg, bloating, anxiety, appetite changesa) Advantages • Bone-sparing (avoids osteoporosis; aseptic necrosisb) a. H. P. Acthar Gel (repository corticotropin injection) [package insert].[15] b. Arnason BG, et al. Mult Scler. 2013;19:130-136.[11] Other Options for Managing Relapse Plasma exchange (plasmapheresis) • Often used in transverse myelitis, NMOa • Consider for patients with spinal cord disease who are still plegic after initial steroid therapy • Typical regimen: 5 exchanges over 10 days • Potential risk of infected lines IVIG • Option for pregnant patients reluctant to use steroids • May provide more complete recovery in optic neuritis compared with steroidsb a. Bonnan M, Cabre P. Mult Scler Int. 2012;2012:787630.[14] b. Magraner MJ, et al. Neurologia. 2013;28:65-72.[15] Comprehensive MS Management Relapse provides opportunity to reassess patients, review treatment strategy, and make adjustments as needed • Evaluate and treat symptoms (eg, mood, fatigue, functional loss) A team approach is valuable • Physical therapy • Occupational therapy • Speech therapy Treat the whole patient Adjusting MS Treatment Acute relapse may be a signal that treatment is not optimal • Has the DMT had time to work? • Are other medical conditions involved (eg, cancer, heart disease)? • Is a switch in DMT indicated? Summary and Key Points • High-dose steroids (IVMP, oral prednisone) are standard treatments for MS relapse − Other options include ACTH, plasma exchange, IVIG • Overuse of steroids may cause serious adverse effects • Manage the whole patient, not just the immediate symptom − Assess and address other medical issues (eg, depression, headache) Abbreviations ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone AE = adverse event DMT = disease-modifying therapy EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Score FDA = US Food and Drug Administration IV = intravenous IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin G IVMP = intravenous methylprednisolone MRI = magnetic resonance imaging MS = multiple sclerosis NMO = neuromyelitis optica RA = rheumatoid arthritis RRMS = relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis References 1. Vollmer T. The natural history of relapses in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2007;256 Suppl 1:S5-13. 2. Möhrke J, Kropp P, Zettl UK. Headaches in multiple sclerosis might imply an inflammatorial process. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69570. 3. Burton JM, O'Connor P, Hohol M, Beyene J. Oral versus intravenous steroids for treatment of relapses in multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD006921. 4. Myhr KM, Mellgren SI. Corticosteroids in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2009;73-80. 5. Morrow SA, McEwan L, Alikhani K, Kremenschutzky M. MS patients report excellent compliance with oral prednisone for acute relapses. Can J Neurol Sci. 2012;39:352354. 6. Sahraian MA, Yadegari S, Azarpajouh R, Forughipour M. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head in multiple sclerosis: a report of five patients. Neurol Sci. 2012;33:14431446. References (cont) 7. Ce P, Gedizlioglu M, Gelal F, Coban P, Ozbek G. Avascular necrosis of the bones: an overlooked complication of pulse steroid treatment of multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:857-861. 8. Ciccone A, Beretta S, Brusaferri F, Galea I, Protti A, Spreafico C. Corticosteroids for the long-term treatment in multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD006264. 9. Andersson PB, Goodkin DE. Glucocorticosteroid therapy for multiple sclerosis: a critical review. J Neurol Sci. 1998;160:16-25. 10. Glaser GH, Merritt HH. Effects of ACTH and cortisone in multiple sclerosis. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1951;56:130-133. 11. Arnason BG, Berkovich R, Catania A, Lisak RP, Zaidi M. Mechanisms of action of adrenocorticotropic hormone and other melanocortins relevant to the clinical management of patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013;19:130-136. 12. Catania A. The melanocortin system in leukocyte biology. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:383-392. References (cont) 13. H. P. Acthar Gel (repository corticotropin injection) [package insert]. Hayward, CA: Questcor Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2012. 14. Bonnan M, Cabre P. Plasma exchange in severe attacks of neuromyelitis optica. Mult Scler Int. 2012;2012:787630. 15. Magraner MJ, Coret F, Casanova B. The effect of intravenous immunoglobulin on neuromyelitis optica. Neurologia. 2013;28:65-72.