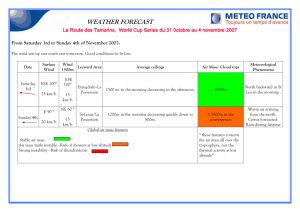

part i: introduction - LSA

advertisement