A Topical Approach to Lifespan Development

advertisement

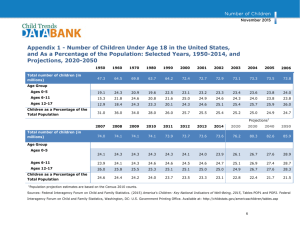

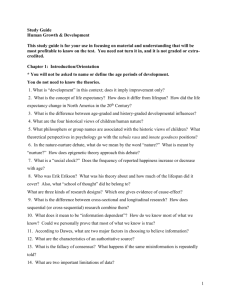

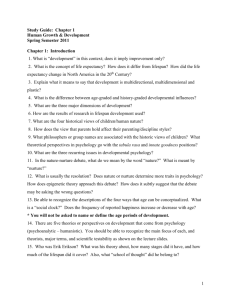

Lifespan Development: A Topical Approach Robert S. Feldman Chapter 1: Orientation What is Human Development? It is a pattern of movement and change Some things change Some things stay the same Movement & change include growth, transition, and decline. The Lifespan Perspective History Studied child development since about 1900. Studied adult development since about 1960. The reason for the difference is cultural change & increased longevity (life expectancy). Life Expectancy Changes Lifespan, the maximum number of years a human being could live (about 120 years) remains relatively constant. Life expectancy, the number of years a person can expect to live when born in a certain place in a certain year, changes. U.S., 1900 47 years U.S., 2005, 77 years (30 year increase) Lifespan Research is Multidisciplinary Where did this information come from? Research and study in many fields of endeavor including psychology, sociology, anthropology, education, and medicine. What types of influences form the context of development? Normative age-graded (cultural) Normative history-graded (historical) e.g., puberty, graduation, retirement e.g., war, famine, earthquakes, terrorism Non-normative life events & conditions (personal) Individual experiences, biology, personality Historical Views of Human Nature Prevailing views of children (human nature) throughout history? Preformationism Original Sin Tabula Rasa Innate Goodness How does each view affect child-rearing practices? Historical View: Preformationism Time: 6th 15th Centuries View: Children are basically small adults without unique needs and characteristics. Effect: Little or no need for special treatment Historical View - Original Sin Time: 16th Century (Puritan) View: Children are born sinful and more apt to grow up to do evil than good. Effect: Parents must discipline children to ensure morality and ultimate salvation. Historical View - Tabula Rasa Time: 17th Century, philosopher John Locke (behaviorist) View: Children are born “blank slates” and parents can train them in any direction they wish (with little resistance). Effect: Shaping children’s behavior by reward and punishment. Historical View – Innate Goodness Time: 18th Century, philosopher Jean Jacque Rousseau (humanist) View: Children are “noble savages” who are born with an innate sense of morality. Effect: Parents should not try to mold them at all. Issue 1: Nature/nurture Nature = biological inheritance (genetics) Nurture = all experience Rousseau (humanists) Locke (tabula rasa) Is that all there is? (Is it neither?) Are they separable? Is it both? What is epigenetic theory? Interaction of nature and nurture Issue 3: Continuity/discontinuity Did the change happen suddenly or gradually (first step; first word)? Is there a marker event? Does the old resemble the new (butterfly)? What are the periods (age groups) of development? These are not standard across textbooks. However, they roughly agree. Prenatal - conception to birth Infancy – birth to about 2 years Early childhood – about ages 2-6 (preschool) Middle & late childhood – about ages 6-11 Adolescence – ages 10-12 or puberty until about ages 18-22 or independence What are the periods (age groups) of development? Early adulthood – ages 20/25 – 40/45 Middle adulthood – ages 40/45 – 60/65 Late adulthood – ages 60/65 on Young old: 65-84 Oldest old: 85+ To what extent are we becoming an age-irrelevant society? People‘s lives are more varied. We have a loose “social clock.” The frequency of reported happiness is about the same for all ages. (78%) Psychoanalytic Theory: Erik Erikson (1902-1994) Eight psychosocial stages in the lifespan Trust v. mistrust Autonomy v. shame/doubt Initiative v. guilt Industry v. inferiority Identity v. confusion Intimacy v. isolation Generativity v. stagnation Integrity v. despair Review of Theories Recommendations: We will not be studying these theories directly in this course. However, their general principles may be referred to in explaining developmental events or processes. If you feel that you need to review them, I would recommend: 1. your textbook 2. any Introduction to Psychology textbook 3. www. allpsych.com 4. http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/perscontents.html 5. Google the word in question, e.g., psychoanalysis, ethology, B. F. Skinner, etc. Data Where do we get our data? What information are we going to believe? What are the techniques of collecting data? Observation Survey/interview: asking questions Standardized Tests Physiological Measures Case Study Life-history records Research Designs Descriptive – includes more detail Correlational – numbers show strength & direction of relationship Used for prediction Ranges from -1.00 to +1.00 (+ is direct; - is inverse) Remember: correlation does not equal causation Research on How People Change across the Lifespan Cross-sectional research: People of different ages are measured in the same year. Cohort effects may occur. These are differences due not to common age, but common experience Longitudinal research: The same people are repeatedly measured across different years. Expensive, time-consuming, dropouts Research on How People Change across the Lifespan Sequential or cross-sequential research: a combination of cross-sectional and longitudinal People of different ages are measure the first year. Then at intervals (e.g., 1, 5, 10 years), the same people are measured again and new groups are added. How Do We Know? Or Do We Just Believe? We are information dependent Bandura – learn from observing others Vygotsky – learn through conversation/communication with others What is the world’s tallest mountain? Why do you believe that it is Everest? How Do We Know? Or Do We Just Believe? Robyn Dawes Why believe that for which there is no good evidence? http://www.fmsonline.org/dawes.html (Or possibly evidence to the contrary?) Most of what we know, we actually believe that we know from authority and consensus. How Do We Know? Or Do We Just Believe? Authority implies that the knowledge is reliable Source is trustworthy; of good reputation No ulterior motives In position to have this type of knowledge However, we often attribute this to consistency of report/public exposure (media). How Do We Know? Or Do We Just Believe? Consensus leads to lack of doubt. (Surely somebody would know if this is false.) The fallacy in consensus is that if the same misinformation (lie) is told often enough, everyone believes it for the truth. Becomes “common sense” (common nonsense) How Do We Know? Or Do We Just Believe? Ways to Know Include Authoritative sources Opinions of others (consistent or not) Personal experience Intuition (with or without confirmation) Reason (I figured it out.) Common sense Data Consider the Limitations of Data Some things cannot be measured, or detected by the five senses Some variables cannot be ethically or possibly submitted to experimentation, only correlation This will not show causality. Correlations may be spurious. There may have been bias in data collection. The interpretation may be incorrect. Information for public consumption may be less accurate. How Do We Know? Or Do We Just Believe? In our culture data trumps other sources Recorded evidence, we can all agree May not agree in Interpretation Tend to discount “pre-scientific” claims to knowledge/understanding We even discount “old” data. How Do We Know? Or Do We Just Believe? This tends to lead to bias against non-data sources, earlier historical times, and less industrialized civilizations. “So easy a cave man could do it.” Don’t bother to study history. How Do We Know? Or Do We Just Believe? Led to the postmodern mindset Truth is relative to the situation and changes across time. There is no ultimate truth that is unchanging. No reliable causes and effects. Reality is socially constructed. Idea that we create knowledge and reality, and it is what we say it is. Hence, we can change it. How Do We Know? Or Do We Just Believe? Contrast the prisca sapientia view. The existence of this knowledge would imply a fixed and unchanging set of principles for operation of the universe and the natural world, including the biological world, and possibly for human nature and the social world. How Do We Know? Or Do We Just Believe? Contrast the prisca sapientia view. Was there a pristine and superior ancient knowledge? How else do you explain the writings of the ancient Greeks, Egyptians, and Hebrews? How to you explain the Mayan calendar and the construction of the Egyptian pyramids? How was it lost? Did the search for it lead to modern science? Practical Critical Thinking 1. Stop to think. 2. Theories are not proven facts. 3. Findings of research can be misinterpreted. 4. Correlations are not evidence of causation. 5. Be very suspicious of politicized research. 6. Beware journalistic media as a source of presentation of scientific findings. 7. Always ask whether the topic is more likely a law or principle rather than a social construction. What is political research? Research that drives or justifies public policy and/or major business decisions is of great interest to powerful people. Research must be funded. Funding agencies can and do influence what topics are funded. There also may be pressure to bias the experimental set-up or to withhold the findings from publication. Evolutionary Developmental Psychology Perspective here has profound effects on: Concern for the tradition of learning/socialization: Judith Harris (Nature Assumption, 1998) says parents not important; genes and peers rule. Views of the meaning of life: Was man made for nature/society or nature/society for man?