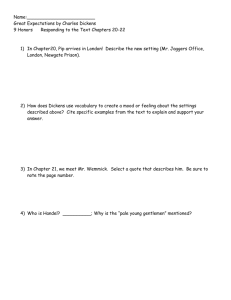

Great Expectations

advertisement

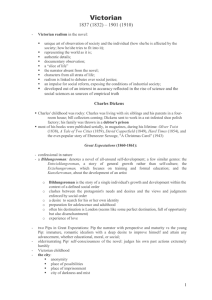

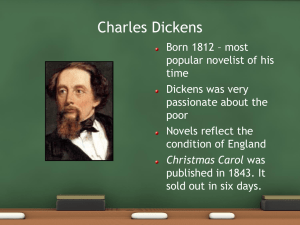

Great Expectations By Charles Dickens Charles Dickens February 7, 1812 – June 9, 1870 • Dickens was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire to John Dickens, a naval pay clerk, and his wife Elizabeth Dickens. • When he was five, the family moved to Chatham, Kent. • When he was ten, the family relocated to Camden Town in London. • His early years were an idyllic time. He thought himself then as a "very small and not-over-particularlytaken-care-of boy". • He talked later in life of his extremely strong memories of childhood and his continuing photographic memory of people and events that helped bring his fiction to life. • His family was moderately well-off, and he received some education at a private school but all that changed when his father, after spending too much money entertaining and retaining his social position, was imprisoned for debt. • At the age of twelve, Dickens was deemed old enough to work and began working for ten hours a day in Warren's boot-blacking factory, located near the present Charing Cross railway station. • He spent his time pasting labels on the jars of thick polish and earned six shillings a week. With this money, he had to pay for his lodging and help to support his family, which was incarcerated in the nearby Marshalsea debtors' prison. • Dickens began work as a law clerk, a junior office position with potential to become a lawyer. • He did not like the law as a profession and after a short time as a court stenographer he became a journalist, reporting parliamentary debate and traveling Britain by stagecoach to cover election campaigns. • His journalism formed his first collection of pieces Sketches by Boz and he continued to contribute to and edit journals for much of his life. • In his early twenties he made a name for himself with his first novel, The Pickwick Papers. Great Expectations • Dickens wrote and published Great Expectations in 1860-1861, and though the novel looks back to an earlier time (1812-1840), the period of composition itself is noteworthy. • Great Expectations looks back upon a period of pre-Victorian development that had become, by 1860, thoroughly historical. However, as a Victorian novel, Great Expectations is itself the product of a dynamic moment in history. Themes of Great Expectations • Ambition and SelfImprovement • Social Class • Crime, Guilt, and Innocence Ambition and SelfImprovement • Affection, loyalty, and conscience are more important than social advancement, wealth, and class. • Dickens establishes the theme and shows Pip learning this lesson, largely by exploring ideas of ambition and self-improvement— ideas that quickly become both the thematic center of the novel and the psychological mechanism that encourages much of Pip’s development. • At heart, Pip is an idealist; whenever he can conceive of something that is better than what he already has, he immediately desires to obtain the improvement. – When he sees Satis House, he longs to be a wealthy gentleman; – when he thinks of his moral shortcomings, he longs to be good; – when he realizes that he cannot read, he longs to learn how. – Pip’s desire for self-improvement is the main source of the novel’s title: because he believes in the possibility of advancement in life, he has “great expectations” about his future. Social Class • Throughout Great Expectations, Dickens explores the class system of Victorian England, ranging from the most wretched criminals (Magwitch) to the poor peasants of the marsh country (Joe and Biddy) to the middle class (Pumblechook) to the very rich (Miss Havisham). • The theme of social class is central to the novel’s plot and to the ultimate moral theme of the book— the inadequacy of material social advancment to bring true happiness. • Pip achieves this realization when he is finally able to understand that, despite the esteem in which he holds Estella, one’s social status is in no way connected to one’s real character. • Drummle, for instance, is an upper-class lout, while Magwitch, a persecuted convict, has a deep inner worth. • Perhaps the most important thing to remember about the novel’s treatment of social class is that the class system it portrays is based on the postIndustrial Revolution model of Victorian England. Dickens generally ignores the nobility and the hereditary aristocracy in favor of characters whose fortunes have been earned through commerce. • The theme of crime, guilt, and innocence is explored throughout the novel largely through the characters of the convicts and the criminal lawyer Jaggers. • From the handcuffs Joe mends at the smithy to the gallows at the prison in London, the imagery of crime and criminal justice pervades the book, becoming an important symbol of Pip’s inner struggle to reconcile his own inner moral conscience with the institutional justice system. • In general, just as social class becomes a superficial standard of value that Pip must learn to look beyond in finding a better way to live his life, the external trappings of the criminal justice system (police, courts, jails, etc.) become a superficial standard of morality that Pip must learn to look beyond to trust his inner conscience. Crime, Guilt, and Innocence • Magwitch, for instance, frightens Pip at first simply because he is a convict, and Pip feels guilty for helping him because he is afraid of the police. By the end of the book, however, Pip has discovered Magwitch’s inner nobility, and is able to disregard his external status as a criminal. Prompted by his conscience, he helps Magwitch to evade the law and the police. • As Pip has learned to trust his conscience and to value Magwitch’s inner character, he has replaced an external standard of value with an internal one. The original ending Dickens’ chose to change the ending of Great Expectations, because according to one of his friends, Bulwer-Lytton (who himself was an author), the ending he had conceived originally was too unhappy for the public to react favourably to his book. The ending you read goes like this: I took her hand in mine, and we went out of the ruined place; and, as the morning mists had risen long ago when I first left the forge, so, the evening mists were rising now, and in all the broad expanse of tranquil light they showed to me, I saw no shadow of another parting from her. Here’s the original, what do you think? It was four years more, before I saw herself. I had heard of her as leading a most unhappy life, and as being separated from her husband who had used her with great cruelty, and who had become quite renowned as a compound of pride, brutality, and meanness. I had heard of the death of her husband (from an accident consequent on ill-treating a horse), and of her being married again to a Shropshire doctor, who, against his interest, had once very manfully interposed, on an occasion when he was in professional attendance on Mr. Drummle, and had witnessed some outrageous treatment of her. I had heard that the Shropshire doctor was not rich, and that they lived on her own personal fortune. I was in England again -- in London, and walking along Piccadilly with little Pip -- when a servant came running after me to ask would I step back to a lady in a carriage who wished to speak to me. It was a little pony carriage, which the lady was driving; and the lady and I looked sadly enough on one another. "I am greatly changed, I know; but I thought you would like to shake hands with Estella, too, Pip. Lift up that pretty child and let me kiss it!" (She supposed the child, I think, to be my child.) I was very glad afterwards to have had the interview; for, in her face and in her voice, and in her touch, she gave me the assurance, that suffering had been stronger than Miss Havisham's teaching, and had given her a heart to understand what my heart used to be. Was Charles Dickens a Christian? • Because of the Scriptural reference at Magwitch's death as well as other Biblical nods in Great Expectations, students often ask if Charles Dickens was a Christian—especially in light of the breakup of his marriage. • The short answer is God only knows. • However Dickens would have defined himself as a Christian and many others have pronounced him a Christian. He Actually Wrote an Account of Jesus’ Life which he forbade to be sold. • In a letter described in the introduction to his The Life of Our Lord, as "perhaps the last words written by Dickens" he describes his own tendency to incorporate but not preach his beliefs in his writings in a time when many used their faith as a way to political and economic advantage: • “I have always striven in my writings to express veneration for the life and lessons of Our Savior, because I feel it. . . But I have never made proclamation Thus this is not a Simple Question to Answer: • One, we scholars know that he was far from perfect. Late in his life Dickens’ marriage floundered. This is common enough, but he placed the blame for the breakup publicly, in the magazine or which he was the editor, entirely upon her. Even among his closest friends, the opinion was held that he behaved badly towards Elizabeth who in spite of this remained respectful of him and later of his memory throughout their separate lives. On the other hand, claims that Dickens had an affair with the young (the age of his daughter) actress Lawless, is more the product of a sexualized modern mindset than a Victorian one. Also one terrible event should not define an individual’s faith not for King David and not for Charles Dickens. • Second, he was a Unitarian, which for many conservative believers means a belief system without any overt claims of Christ’s divinity. However, his friend Foster maintains that he was drawn to the movement because of its active interest in the poor and that he, in fact, remained orthodox in his belief throughout his life. It is true that especially in the Victorian period there were many Unitarians who remained orthodox and in fact evangelical in their Christian beliefs. As for evangelicals, especially Methodists, Dickens had formed a very low opinion of them early in his life for their tendency to allow anyone who claimed to spirit to be a minister. Meanwhile he did not trust the high church tendencies within the very formal elements of the Church of England. His friend Foster while maintaining the safety of Dickens' belief, rather ambiguously refers to it as being characterized by a "depth of sentiment rather than clearness of faith" (ii, 147). • Third in a time when faith was often used as a way to raise oneself up socially, Dickens refused to make public pronouncements about his belief system. In fact not long before he died he was queried by a clergyman about the ideas of Christianity within his novels. In response he wrote: “I have always striven in my writings to express veneration for the life and lessons of Our Savior, because I feel it. . . But I have never made proclamation of this from the housetops” (Qtd. in the Forward to Life of Our Lord 4). Yet in spite of these questions Dickens seems to have held to the last a reliance upon faith When Dickens bade farewell to his sixteen-year-old son Plorn, who was off to Australia, he wrote: "I put a New Testament among your books, for the very same reasons, and with the very same hopes that made me write an easy account of it for you, when you were a little child...." (Qtd in Johnson, ii: 1100). In spite of this vagueness of orthodoxy there is no debate among scholars that Christian principles and Christian images of at the center of Dickens’ attitudes towards the poor and towards the reclamation of individuals. • Steven Marcus, the famous Dickens scholar, says forthrightly that of course Dickens was a Christian.” • The English writer George Orwell said of Charles Dickens: “he ‘believed’ undoubtedly.