English 278

advertisement

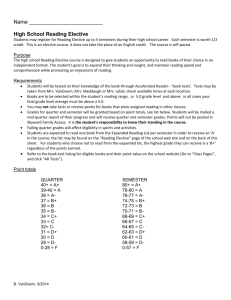

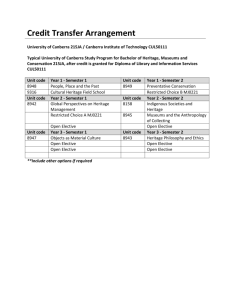

. UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH 53880 ENGLISH STUDIES 278 COURSE PROSPECTUS 2016 COURSE COORDINATOR: Dr Megan Jones Room 572 808 2048 meganj@sun.ac.za Webpage: www.sun.ac.za/deptenglish THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH VISION For more than three centuries, the Cape has served as a passageway linking West and East, North and South. This conjunction of the local and the global, of time and place, consciously informs our goals in the Department of English at Stellenbosch University. In our teaching and research, we ask how – and why – modes of reading, representation and textuality mean differently, in different times and locales, to different constituencies. MISSION We envisage the discipline as a series of transformative encounters between worlds and texts, a process of reading, thinking, debate and writing which is well-placed to contribute not only to our students’ critical and creative knowledge of ‘English’ as a discipline, but also to the possibilities for change in Stellenbosch, a site still marked by racial and economic disparity. If novels by Chimamanda Adichie and Abdulrazak Gurnah, poetry from the Caribbean, and articles by Njabulo S. Ndebele can prompt revised recognitions of racial, cultural and gendered identities, so too can fiction by Olive Schreiner or poetry by Walt Whitman open us to challenging points of view about the relation between identity and inherited ideas, postcolonial theory and the politics of the local. Our research areas (among them queer theory, critical nature studies, diaspora studies, life writing, visual activism, the Neo-Victorian and contemporary poetry) contribute to our diverse ability to position ‘English’ as a space of literatures, languages and cultural studies which engages a deliberately wide range of thought, expression and agency. We aim to equip our graduates with conceptual and expressive proficiencies which are central to careers in media, education, NGOs, law, and the public service. Simultaneously, we recognize that capacities of coherent thought and articulation can play an important role in democracy and transformation. In the English Department, we encourage a collegial, inclusive research community in which all participants (staff, postgraduates and undergrads, fellows, professors extraordinaire and emeriti) are prompted to produce original and innovative scholarship. To this end, there is a programme of regular events in the department, among them research seminars featuring regional and international speakers; workshops on research methods, proposal writing, and creative writing, and active reading and writing groups. Such platforms complement the department’s vibrant InZync poetry project, and the digital SlipNet initiative (http://slipnet.co.za/), enabling us to create a teaching and learning environment in which the pleasures and challenges of ‘English’ as ‘englishes’ can be publicly performed and debated, in Stellenbosch and beyond. 1 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE COURSE 3 2. COURSE CONTENT 3 2.1 Lectures 3-5 2.2 Lecture schedule 6-7 2.3 Elective seminars 8 2.4 First semester elective seminar timetable 9 2.4 Second semester elective seminar timetable 2.5 Elective seminar descriptions 3. ASSESSMENT 19 3.1 Continuous assessment 19 3.2 Progress mark 19 3.3 Final mark 20 3.4 Incomplete 20 3.5 Missed work 21 4. TESTS 21 4.1 Test marks 21 4.2 Test dates 22 5. ESSAYS & ASSIGNMENTS 22 5.1 Submission of written work 22 5.2 Late submissions 23 5.3 Plagiarism 23 6. POSTGRADUATE COURSES 24 7. BURSARIES 24 8. STAFF 25 10 11-19 2 ENGLISH STUDIES 278 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE COURSE The lecture component of the English 278 course develops students’ familiarity with the disciplinary scope of English literary and cultural studies. Course materials range from early modern to contemporary literature and include other expressive media, such as film. In both semesters students must also choose an elective seminar from a range of options. The course builds on work done in English 178, differing from it mainly in that it requires you to do much more work on your own. You will note that the list of setworks is longer than for the first-year course, and although you have double the lectures per week, these texts are not dealt with in the same amount of detail as in the first year. Please note that you are expected to read all the setworks for your course. Essays and tests must demonstrate your thorough grasp of and engagement with the texts and the relevant course content. Study guides such as SparkNotes will not equip you to meet the course requirements. We suggest that you begin reading for each term during the holidays. 2. COURSE CONTENT You have four periods per week, two fifty-minute lectures and one double-period seminar class in a small group, usually of about 18 students. 2.1 LECTURES Students are expected to attend all lectures, to read all the prescribed texts and any other material the lecturer makes available. If, because of clashes with lectures from other courses, you cannot attend some lectures you must consult with the course co-ordinator before enrolling in the course. LECTURE TIMES Monday Tuesday 14:00 – 14:50 11:00 – 11:50 All lectures in Arts 230 There are six lecture series in the course of the year (three per semester). More information regarding the lecture series (including prescribed books) may be found on pp. 4-5 of this prospectus; the semester schedules appear on pp. 6-7. 3 SEMESTER 1 SERIES 1: SHAKESPEARE’S THE TEMPEST AND ITS AFTERLIVES This section of the course begins with Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest, in order to show how one can understand it in its own time and place, England in the early 17 th century. We then move on to the question of literary and theatrical appropriation to think about a range of issues related to the influence of a canonical work beyond its own historical moment. Why did The Tempest remain an influential play for more than 400 years? Why are we still studying it in South Africa in the 21 st century? Why did Shakespeare become such an important part of English syllabuses throughout the world? What happens when a drama is restaged in places and times that are so remote from their point of origin? Why was The Tempest rewritten and revisited by authors such as the Martiniquan Aimé Césaire, an important figure in the struggle against colonialism in Africa and a founding figure of the négritude movement, and Marina Warner, a British feminist and mythographer? This section of the course, then, focuses on the way literary texts move through time and space, acquiring new kinds of audiences and speaking to new concerns across generations. Shakespeare, W. The Tempest. Norton Critical Edition, 1995. Other texts will be provided. SERIES 2: COMPLICATED I, COMPAGINATED WE This lecture series examines some of the ways in which poets since the Renaissance have come to terms with the idea of an individual self and its relation to others. Starting with the early modern emergence of the conception of a self-responsible and fundamentally free human subject as expressed in works by William Shakespeare, John Milton and John Donne, this course will specifically consider the ways in which this newly complex self has been imagined to relate to the world and to co-exist and connect with others, both intimately and socially. In the course of the series we contrast these concepts and the rhetorical strategies they inspired to those in twentieth century poetry expressing intimacies in a new social complex; among other things, we read about women’s love, queer love and the proliferation of love. Course readers will be provided. SERIES 3: FAMILIAR MONSTERS: ON BEING(S) UNCANNY In this section of the module, we inventively shift, cut and merge ideas from different historical contexts and modes of representation in order to initiate debates around the enigmatic idea of ‘uncanny being’. We begin by thinking about ‘the monstrous’ in Mary Shelley’s famous novel Frankenstein. An obsessive scientist creates a monster. To many people, the basic concept is unsettling but familiar, a cultural formula that since 1818 has been copied numerous times, mutating into versions of androids, aliens, cyborgs. These creatures are unnerving because they are simultaneously strange and familiar. In some respects, they resemble humans in both appearance and action, and yet often we suppress such similarity, emphasizing their difference. Extending our thinking about human and post-human forms, the next section of the course focuses on Neill Blomkamp’s film Chappie (2015). To what extent are viewers moved by a childlike, would-be tough guy police robot in a futuristic Johannesburg? How are representations of gender, nurture and technology cinematically mobilised to influence our responses? In thinking about both Chappie and Frankenstein’s creature, whatever else these beings have in common, the most evident link is us. Humans. What are the implications for the creation of uncanny categories of identification and refusal? Shelley, M. Frankenstein. Wordsworth Classics, 1999. Students must attend two lectures per week (in Arts 230) 4 SEMESTER 2 SERIES 4: ENVIRONMENTAL IMAGINARIES This component introduces students to environmental imaginings in written literary forms from different spatialities (geographies) and temporalities. Focusing first on a local literary text, it examines the narrative treatment of human engagement with the physical landscape, nineteenth century philosophies of nature, colonial exploitation and othering of the environment, gender and race. The course then traces the continuities and disjunctions of these issues depicted in a contemporary dystopian novel set in an apocalyptic/postapocalyptic context. Schreiner, O. The Story of an African Farm. Penguin, 2005. McCarthy, C. The Road. Picador, 2006. SERIES 5: (DIS)PLACEMENT AND DIASPORA This series will focus on texts relating to ideas about home, belonging and dispossession. We will read selected short stories from Zoe Wicomb’s collection You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town to problematize questions of belonging from the shifting perspective of Frieda Shenton, in her search for a sense identity and belonging, from the mid-50s to the 80s in South Africa/Namaqualand and Cape Town. The series ends with lectures on the Indian diaspora community in Kenya. Indians first arrived in Kenya as indentured labourers and their sense of displacement and belonging changes according to the political shifts in Kenya in the 20th century. Wicomb, Z. You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town. Umuzi, 2008. Vassanji, M. G. The In-Between World of Vikram Lall. Vintage, 2005. SERIES 6: BODIES IN THE WORLD In this concluding series, working with word and image, we will explore representations of ‘the body’ in examples of contemporary poetry, and film. The lectures will illustrate some of the ways in which bodies simultaneously reflect and project upon the world, prompting us to read physical embodiment as both confirming and contesting dominant cultural ideas about identity. In the first part of the lectures, we will pay close attention to poetry and the body, treating poems and bodies as complex sites for the performance of desire, vulnerability, and celebration. Here, using a range of contemporary poetry, we will consider how bodies are located in time, place and culture. Our focus will fall not simply on bodies as the subject matter of poems, but on poetic form as an inventive linguistic-physical embodiment of language, voice, and gesture. The second part of the lectures will consider Stephen Frears's Dirty Pretty Things (2002). This film concerns questions of the human body as disposable, commodified, and subject to biopolitics. Appreciating the kinetic, sensory nature of film as a cultural form in which audience response is conventionally based on sight and sound, we will see that in a cinematic interplay of the visible and the secret, Frears draws attention to the reduction of bodies to saleable organs, commenting especially on the plight of illegal immigrants in contemporary London. Relevant texts will be provided. Students must attend two lectures per week (in Arts 230) 5 2.2 LECTURE SCHEDULE English 278 1st Term 2016 All students attend all lectures. Venue: Arts 230 Monday 14:00 1 Feb Series 1: Introduction (D Roux) 8 Feb Series 1: The Tempest (D Roux) 15 Feb Series 1: The Tempest (D Roux) 22 Feb Series 1: The Tempest (D Roux) 29 Feb Series 2: Introduction (S Viljoen, D de Villiers) 7 March Series 2: Paradise Lost (D de Villiers) 14 March Series 2: Poetry (S Viljoen) Tuesday 11:00 2 Feb Series 1: The Tempest (D Roux) 9 Feb Series 1: The Tempest (D Roux) 16 Feb Series 1: The Tempest (D Roux) 23 Feb Series 1: The Tempest (D Roux) 1 March Series 2: Paradise Lost (D de Villiers) 8 March Series 2: Paradise Lost (D de Villiers) 15 March Series 2: Poetry (S Viljoen) Recess 19 - 28 March English 278 2nd Term 2016 Monday 14:00 28 March Tuesday 11:00 29 March PUBLIC HOLIDAY Series 2: Poetry (S Viljoen) 4 April 5 April Series 2: Poetry Series 2: Conclusions (S Viljoen) (S Viljoen, D de Villiers) 11 April 12 April Series 3: Introduction Series 3: Frankenstein (S Murray) (S Murray) 18 April 19 April Series 3: Frankenstein Series 3: Frankenstein (S Murray) (S Murray) 25 April 26 April Series 3: Frankenstein Series 3: Chappie (S Murray) (R Oppelt) 2 May 3 May 5 May (Mon timetable) PUBLIC HOLIDAY Series 3: Chappie Series 3: Chappie (R Oppelt) (R Oppelt) 9 May 10 May Series 3: Chappie Series 3: Chappie (R Oppelt) (R Oppelt) 6 English 278 3rd Term 2016 All students attend all lectures. Venue: Arts 230 Monday 14:00 18 July Series 4: African Farm (L Green) 25 July Series 4: African Farm (L Green) 1 Aug Series 4: The Road (T Slabbert) 8 Aug Series 4: Environmental Imaginaries (T Slabbert) 15 Aug Series 4: The Road (T Slabbert) 22 Aug Series 5: You Can’t Get Lost in CT (N Bangeni) 29 Aug Series 5: You Can’t Get Lost in CT (N Bangeni) Tuesday 11:00 19 July Series 4: African Farm (L Green) 26 July Series 4: African Farm (L Green) 3 Aug Series 4: The Road (T Slabbert) 9 Aug PUBLIC HOLIDAY 16 Aug Series 5: You Can’t Get Lost in CT (N Bangeni) 23 Aug Series 5: You Can’t Get Lost in CT (N Bangeni) 30 Aug Series 5: Vikram Lall (T Steiner) Recess 3 - 11 September English 278 4th Term 2016 Monday 14:00 12 Sept Series 5: Vikram Lall (T Steiner) 19 Sept Series 5: Vikram Lall (T Steiner) Tuesday 11:00 13 Sept Series 5: Vikram Lall (T Steiner) 20 Sept Series 6: Poetry (S Murray) 26 Sept 27 Sept Series 6: Poetry (S Murray) 3 Oct Series 6: Poetry (S Murray) 10 Oct Series 6: Dirty Pretty Things (N Sanger) Series 6: Poetry (S Murray) 4 Oct Series 6: Dirty Pretty Things (N Sanger) 11 Oct Series 6: Dirty Pretty Things (N Sanger) 17 Oct 18 Oct Series 6: Dirty Pretty Things (N Sanger) Series 6: Dirty Pretty Things (N Sanger) 7 2.3 ELECTIVE SEMINARS An elective is a structured seminar group; each student will attend one seminar in each semester (that is, two seminars over the course of the year). Timetables and course descriptions are given in this prospectus (pages 9-19). Seminar classes form part of the process of continuous assessment, without which no final mark (“prestasiepunt”) can be assigned. Merely submitting the written work will not be accepted as an adequate substitute for attendance at and participation in the discussions; please note that attendance is compulsory (B.Ed students should note that, if they are off-campus during the second semester, they have to alert their seminar lecturer within the first two weeks of the third term; it is also the student’s responsibility to keep track of assignments and to submit any required work by the official deadlines). As in first-year English, the aim of these seminar classes is to develop your reading and essay-writing skills. Electives proceed by means of class discussion and interaction with the lecturer, so students are urged to get into the habit of preparing for and participating in seminar group discussion. Lecturers welcome contributions and questions from students. Learning is an active process, and we encourage our students to be critical and develop their own ideas and insights. Passive or rote learning is not what university education is about. Many lecturers now factor class participation into the seminar mark. SEMINAR ENROLMENT In both semesters you must enrol for one seminar on SUNLearn. Please consult the semester timetables (pp. 9 and 10) and carefully read the elective descriptions (pp. 11-19) before you make your choice. If the class is already full, you will have to choose another elective. The number of students per elective seminar is usually limited to 18, and first come will be first served. Students will not be allowed to enrol for any seminar they attended in a previous semester (this also goes for those who are repeating English 278). Where enrolment for an elective is fewer than 12, that elective may have to be cancelled. Class lists will be posted on the second-year notice board (on the left outside Room 223 of the Arts Building). First semester: You must enrol, on SUNLearn, for the elective of your choice before or during the first week of the first term. The first semester elective timetable appears on p. 9. If the class is already full, you will have to choose another elective. Remember that you are not allowed to enrol for any seminar you have attended in a previous semester. Seminars commence in the second week of the first term. Second semester: You must enrol, on SUNLearn, for the elective of your choice (online enrolment will be enabled after the end of the first semester, from 24 June until 14 July). The second semester elective timetable appears on p. 10. If the class is already full, you will have to choose another elective. Remember that you are not allowed to enrol for any seminar you have attended in a previous semester. Seminars commence in the first week of the third term. Please note: You are not allowed to change your seminar group without permission. If a genuine timetable clash should occur, contact the department’s administrative officer (colettek@sun.ac.za) or the course co-ordinator immediately, so that you might be assigned an alternative group. Attendance at seminars is compulsory. 8 2.4 FIRST SEMESTER ELECTIVE SEMINAR TIMETABLE Lecturer Gr Elective Seminar Time 1 T Slabbert Intertextuality and Metafiction Mon 15.00 & 16.00 2 G Andrews Masculinities and Queer Identities Mon 15.00 & 16.00 3 R Oppelt Stages of Cinema Tue 14.00 & 15.00 4 B Fortuin (Queered) Masculinity/ies Tue 14.00 & 15.00 5 D Roux Thinking Nonfiction Tue 15.00 & 16.00 6 L Green Documentary Realism on Screen Tue 15.00 & 16.00 7 N Bangeni Language as Identity Wed 9.00 & 10.00 8 D de Villiers American Showdown Wed 14.00 & 15.00 9 D Roux Thinking Nonfiction Wed 14.00 & 15.00 10 M Geustyn Littoral Literatures Wed 15.00 & 16.00 11 A Marais Feminist Revision of Fairy Tales Wed 15.00 & 16.00 12 L Roux Bitterkomix Thu 14.00 & 15.00 T Slabbert Intertextuality and Metafiction Thu 14.00 & 15.00 14 D Tyfield Michael Ondaatje, Language, Hospitality Thu 15.00 & 16.00 15 T Steiner Conversations Across the Continent Thu 15.00 & 16.00 16 L Smit Fictionalising the Self Fri 9.00 & 10.00 17 W Mbao The Autobiographical Impulse Fri 10.00 & 11.00 18 A Pieterse Representations of Witchcraft in SA Fri 10.00 & 11.00 19 B Fortuin (Queered) Masculinity/ies Fri 11.00 & 12.00 20 TBA TBA TBA TBA TBA TBA 13 21 Final venues for the seminars will be on SUNLearn. 9 2.5 SECOND SEMESTER ELECTIVE SEMINAR TIMETABLE Gr Elective Seminar Lecturer Time 1 K Highman The Art of the Literary Essay Mon 15.00 & 16.00 2 W Mbao Writing Against Apartheid Mon 15.00 & 16.00 3 W Mbao Writing After Apartheid Tue 14.00 & 15.00 4 M Jones Land, Community and Indigeneity Tue 14.00 & 15.00 5 D Roux Using Literary Theory: Foucault Tue 15.00 & 16.00 6 Oppelt/Green Decoding the City Tue 15.00 & 16.00 7 N Bangeni Language as Identity Wed 9.00 & 10.00 8 D de Villiers Introduction to the Beats Wed 14.00 & 15.00 9 R Oppelt The Passion of New Beginnings Wed 14.00 & 15.00 10 G Andrews Masculinities and Queer Identities Wed 15.00 & 16.00 11 A Marais Feminist Revision of Fairy Tales Wed 15.00 & 16.00 12 T Slabbert “Something Betwixt and Between” Thu 14.00 & 15.00 M Jones Land, Community and Indigeneity Thu 14.00 & 15.00 14 L Green Documentary Realism on Screen Thu 15.00 & 16.00 15 D de Villiers Terminal Spectacles Thu 15.00 & 16.00 16 TBA TBA Fri 9.00 & 10.00 17 A Pieterse Representations of Witchcraft in SA Fri 10.00 & 11.00 K Highman The Art of the Literary Essay Fri 10.00 & 11.00 D Tyfield Michael Ondaatje, Language, Hospitality Fri 11.00 & 12.00 TBA TBA TBA 13 18 19 20 Final venues for the seminars will be on SUNLearn. 10 2.6 ELECTIVE SEMINAR DESCRIPTIONS MASCULINITIES AND QUEER IDENTITIES IN SOUTH AFRICAN FICTION [1st and 2nd semesters] Grant Andrews Masculinity has historically been tied to the familiar patriarchal roles of protection, providing, leadership, stoicism and control. In addition, in South Africa, straight, white, affluent male identity has often been afforded the highest degree of legitimacy and centrality, constructing any deviation from this as other or outsider. Literature offers a powerful way of interrogating and destabilising these notions. The course will look at how masculinities have been constructed within post-apartheid South African fiction, and how queer identities confront the expectations of masculinity. With the rise in critical engagement with masculinities, there has been a movement towards negotiating new possibilities for gender expression and to challenge conceptions of how masculinity can be performed and represented. The course will investigate two novels, by K. Sello Duiker and Mark Behr respectively, which tackle these shifts. We will combine literary analysis with important concepts in gender studies and consider the role that shifting representations can have within the South African context. Duiker, K. Sello. The Quiet Violence of Dreams, 2001. Behr, Mark. Kings of the Water, 2009. LANGUAGE AS IDENTITY [1st and 2nd semesters] Nwabisa Bangeni This course aims to further the understanding and knowledge of language as more than a set of signs and symbols for communication. Some of the concerns that this course seeks to deal with include the manifestation of racial and cultural beliefs and values in language, cultural dimensions of space, time and gender as reflected in language, as well as language attitudes. South Africa, with its myriad of languages and cultures, offers a rich and contemporary sphere in which to explore these matters. Wicomb, Zoë. The One That Got Away. Umuzi, 2008. Kingsolver, Barbara. Poisonwood Bible. Faber and Faber, 2000. AMERICAN SHOWDOWN: IDENTITY IN THE WESTERN [1st semester] Dawid de Villiers This course explores the Western as a genre in which American identity—both individual and national—has been, and continues to be, defined, negotiated, explored, and critiqued. We will consider a range of seminal and representative texts, both film and literature, in order to interrogate the iconography, ideology, and aesthetics of the Western. As a framework for our discussions students will read two of Frederick Jackson Turner’s influential essays on the American Frontier. The prescribed literary works are Stephen Crane’s short story, “The Blue Hotel” (1898), and Cormac McCarthy’s revisionist novel, Blood Meridian (1985). The films under consideration are: John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), both starring John Wayne, as well as Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) and Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992). Students interested in this course need to be willing and able to attend screenings of the five prescribed films at designated times outside regular class hours (to be decided on in class). Crane, Stephen. “The Blue Hotel.” 1898. [Available on SUNLearn] McCarthy, Cormac. Blood Meridian, or, An Evening Redness in the West. 1985. Vintage, 1990. INTRODUCTION TO THE BEATS [2nd semester] Dawid de Villiers In the 1960s American society suddenly found its conservative and complacent norms and values openly challenged by the nation’s youth. The impetus for this social tremor may in part by traced back to a group of writers active in the 1940s and 1950s, collectively known as the Beat Generation, or the Beats. This course aims to introduce students to three definitive texts from this era, namely Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Allen Ginsberg’s 11 Howl, and Other Poems, and William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch (extracts from this last text will be placed on reserve). We will examine these texts in relation to both the social and cultural contexts in which they took shape, specifically focusing on the critique of society offered respectively in each work, while also considering the relationship between this critique, the writers’ world-views, and the radical, experimental forms assumed by much of their work. Burroughs, William S. Naked Lunch. [Extracts on SUNLearn] Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. Penguin, 2000. Ginsberg, Allen. Howl, and Other Poems. City Lights, 2001. TERMINAL SPECTACLES, INTERMINABLE SPECULATIONS: AN EXPLORATION OF APOCALYPSE IN FILM [2nd semester] Dawid de Villiers The end of humankind – or of what is taken to be its dominant institutions and social formations – has long been a source of fascination, imaginative speculation and existential anxiety. An astonishing range of novels, poems, paintings, films, etc. have exploited the spectacular potential of apocalypse and have in the process raised questions about how we do, ought to, or might, live our lives – and why, indeed, we live them. Against the backdrop of a number of critical and theoretical texts that in distinctive ways consider “ends” and “endings” – ranging from Frank Kermode’s and Peter Brooks’ reflections upon the relationship between apocalypse/closure and narrative to JeanFrançois Lyotard’s engagement with the distant terminal event of “solar death” and Slavoj Zizek’s assertion that we are “living in the end times” – we will in this seminar explore a sample of approximately eight films dealing with the imminent, potential or achieved end of the world (as we know it). Students signing up for this seminar are assumed to be willing and able to attend screenings of the prescribed films outside of regular class hours. Additional readings will be provided. (QUEERED) MASCULINITY/IES IN SOUTH AFRICAN CULTURAL AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS [1st semester] Bernard Fortuin This seminar looks at South African literary and cultural representations of male homosexual desire from 1948 to 2013. It employs Michel Foucault’s concept of biopolitics/biopower and Judith Butler’s heterosexual matrix amongst others to engage with South Africans’ literary and cultural representations of male homosexuality. The country is seen to associate homosexuality with a similar sense of pathology, as was the trend in the colonial centre. Later, as the continent comes to rely less on Western frameworks of self-definition, there is an indigenisation of these Western identities as they rub up against conservative patriarchy and homophobia. The course engages with texts set in the various institutions that form/ed the foundation of the modern capitalist state that is South Africa. They reflect the ways in which societies geared at institutionalising (white) heteronormativity still retained/enabled space for a queering of self and other which in turn allows moments of intimacy and transgressive dissidence. The homosexual man and his interplay with the heteronormative family, army, schools and prisons reflect the racist and gendered nature of South African society and the problematic way in which femininity has become conflated with a state of subjection. Similarly, homosexuality is seen to become a generative site where performances of masculinity and gender can be queered. Proteus. Dir. John Greyson & Jack Lewis. Domino Films. 2007. DVD. Martin, Karen, and Makhosazana Xaba, eds. Queer Africa: New and Collected Fiction. Modjaji Books, 2013. De Nooy, Richard. The Big Stick. Jacana Media, 2011 Duiker, K. Sello. The Quiet Violence of Dreams. Kwela Books, 2001. [Extracts will be provided on SUNLearn] Brandhouse. “Papa Wag vir Jou”. Drive Dry Campaign. 2011. LITTORAL LITERATURES: IMAGINING THE BEACH [1st semester] Maria Geustyn “The beach is an ambiguous place, an in-between place.” – John Mack, The Sea 165 “Beaches are places of contact, of confrontation and friction: first-comers always arrive on a beach.” – Susan Hosking et al, Something Rich & Strange vii. 12 The “littoral zone” is generally accepted to refer to the stretch of space extending from the high water mark on the beach to the section of the ocean that is permanently submerged (this applies to lakes and rivers as well). However, due to the changing natures of tides and shorelines, there can be no single definition for the littoral zone, and it finally remains an ambivalent and ambiguous space. This course aims to explore the representation of the littoral space of the beach in South African literature as a significant site of history, memory and belonging across three distinct chronological temporalities: the beach as “contact zone” (Pratt 1996) in colonial encounters, a site of constitutionalised segregation, and a present, post-apartheid state of ‘entanglement’ (Nuttall 2009). This elective will draw on contrapuntal readings of selected texts – including Zoë Wicomb’s You Can’t Lost in Cape Town, which is prescribed for your lectures – published in each of these temporalities, to explore ways of thinking through the littoral towards an understanding of the ebb and flow in states of being, and the possible construction of a postapartheid aesthetic. Luís Vaz de Camões. The Lusiads, 1572. [Excerpts will be made available on SUNLearn] Murray, Sally-Ann. Open Season, 2006. Additional readings will be provided. DOCUMENTARY REALISM ON SCREEN [1st and 2nd semesters] Louise Green This course will investigate various ways in which the real has been imagined through the medium of documentary film. We will watch a selection of past and present documentaries in order to analyse the techniques employed in conveying a sense of the real. The films will include early documentaries such as, Dziga Vertov, Man with a Movie Camera as well as contemporary documentaries such as American Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine and films from South African documentary film-makers, such as Francois Verster. The course will also invite students to look critically at a series of concepts including the real itself, ideology, documentary, genre, montage, narrative and fiction. The course material will include a series of theoretical readings on realism and documentary film. Readings will be provided. THE ART OF THE LITERARY ESSAY [2nd semester] Kate Highman This elective engages with questions of literary form and with the fundamentals of critical and imaginative reading and writing through examining the art of the literary ‘essay’. The literary essay differs from the academic essay, a quite specific genre itself, but the two – clearly – are related, and the elective hopes to guide participants towards developing not only their critical reading skills, but greater self-reflexivity about their own critical writing, through close engagement with the ‘art’ of the essay. All of the essays we study are chosen for their achievements of form, style and voice as much as for their content, and in the seminars we will engage with these aspects, considering the ‘art’ of the set essays, as well as what makes them ‘literary’, or why we choose to call some texts ‘literary’ and others not. The essay is a famously eclectic form – in the words of Christy Wampole, ‘[t]he essayist samples more than a D.J.: a loop of the epic here, a little lyric replay there, a polyvocal break and citations from greatnesses past, all with a signature scratch on top’ – but in our elective we will try to think about the limits of the literary essay as form. What distinguishes the literary essay from memoir or short story? What demarcates fiction from non-fiction? The literary essay is a form of wide geographical and historical reach, and we will encounter writing from various places and periods, for the most part grouping essays thematically, and reading them ‘contrapuntally’, to borrow Edward Said’s formulation. We will study an essay by the sixteenth-century French writer Michel de Montaigne, usually described as the originator of the essay as literary form, as well as the works of other famous essayists – William Hazlitt, G.K. Chesterton, James Baldwin, Walter Benjamin, Virginia Woolf, George Orwell, Joan Didion, Janet Malcolm, David Foster Wallace, Binyavanga Wainana. In the final classes of the semester we will focus particularly on essay writing in South Africa, and current debates about the increased popularity of literary non-fiction in post-apartheid South Africa, considering essays by Njabulo Ndebele, Ivan Vladislavic, Antjie Krog, and Rustum Kozain. Each week allows for careful reading of either one or two essays (depending on length) and one secondary reading, or excerpt thereof, with the aim of fostering close reading skills and helping students develop their own critical voices. Lopate, Philip. The Art of the Personal Essay: An Anthology from the Classical Era to the Present. Anchor, 1995. A course reader with select essays and secondary readings with be made available. 13 LAND, COMMUNITY AND INDIGENEITY [2nd semester] Megan Jones In this elective we will explore questions of land, ownership and belonging in the lives of indigenous peoples from South Africa, the United States, Australia and New Zealand. All of these countries share colonial histories that witnessed the marginalisation and even genocide of their native inhabitants, many of whose descendants remain trapped at society’s edges in Reserves— what were once called “Bantustans” in South Africa. How do Native American, Aboriginal and indigenous communities retain claims to land from which they have long been dispossessed? What have the effects of this dispossession been on the social and filial networks of such communities? Bearing in mind the locational specificity of each of the given texts, we will draw on the techniques of comparative reading in order to ask what literature and culture can do to recover indigenous ways of being within the pressures of modernity. Erdich, Louise. The Roundhouse, 2012. Sol T. Plaatje Native Life in South Africa, 1914. Caro, Niki (dir.). Whale Rider, 2002. A selection of poems by Oodgeroo Noonuccal (Kath Walker) will be provided on SUNLearn HAPPILY EVER OTHER: FEMINIST REVISION OF FAIRY TALES [1st and 2nd semesters] Adri Marais Considering the on-going popularity of fairy tales – in both contemporary literature and popular films like Maleficent (2014) and Snow White and the Huntsman (2012) – this course aims to introduce students to two intersecting areas of study, namely fairy tale studies and feminist revision. We will briefly explore the fairy tale as a literary text – its history and social significance – before introducing the feminist movement that popularised the revision of classic fairy tales in the 60s, 70s and 80s. Paying special attention to short stories by writers like Angela Carter, Jane Yolen and Emma Donoghue, amongst others, we will consider how such revisions criticise, subvert and renew the classic fairy tales which marginalise, other and disempower women, before taking a comparative look at some contemporary fairy tale films. The aim of the elective is not only to familiarise students with the history of the fairy tale and the literary movements that have shaped the type of revisions currently popularised in mainstream movies, but also to critically consider the continued relevance of feminist revision as an act of disruption and literary reinvention. A selection of short stories by Angela Carter, Jane Yolen and Emma Donoghue will be provided. Films: Maleficent (2014) and Snow White and the Huntsman (2012). Secondary material will be made available on SUNLearn. THE AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL IMPULSE [1st semester] Wamuwi Mbao As a means of writing, autobiography eludes the open-ended nature of history by concluding in some form of suspended present. It dwells in the past for the duration of its narrative, only to culminate at whatever point the author chooses to signpost as the present. Further, it sustains an illusion of reality through its claims to realism: autobiography is constantly at pains to hide the creative nature of its being. That is, it seeks to present itself as a narrative that emerges naturally, rather than being creatively and actively shaped. This elective seeks to map the complexities of the autobiographical impulse via selected primary texts and a selection of secondary materials. Johnson, Shaun. The Native Commissioner. Johannesburg: Penguin, 2006. Coetzee, J. M. Summertime. London: Secker& Warburg, 2001. WRITING AFTER APARTHEID [2nd semester] Wamuwi Mbao This course explores post-Apartheid literary subjectivities via close reading of two primary texts. It provides both a historical overview of the post-Apartheid literary scene, as well as an opportunity for engagement with relevant theories, debates and issues to this period. Wicomb, Zoe. Playing in the Light. Umuzi, 2006. Coetzee, J. M. Disgrace. London: Secker & Warburg, 1999. 14 WRITING AGAINST APARTHEID [2nd semester] Wamuwi Mbao This course explores the category of South African literature via a series of primary and secondary texts. Participants in the elective will gain a historicized understanding of how South African writing in English participated in the struggle against Apartheid. Paton, Alan. Cry the Beloved Country. London: Penguin, 2004. La Guma, Alex. A Walk in the Night and Other Stories. Illinois: Northwestern. 1968. STAGES OF CINEMA [1st semester] Riaan Oppelt ‘Classic’ is a term that can often occupy two reference points in our thinking: we think of historically esteemed works of art, music, architecture and literature that have become synonymous with certain periods, epochs or ages in critical and popular understanding. The term denotes age and an appreciation or reverence of age in a product, admired in design as much as it is in historical weight. We also sometimes tend to use the term ‘classical’ in a shorthand way to refer to something more recent but still tantamount to a body of work: a song on the radio barely a few months old, or a film recently released could as quickly be described as a ‘classic’, an in-the-moment appraisal of a product of modernity, of the now, because it has a certain familiarity to it. Focusing on film studies, we will attempt to unpack the idea of familiarity and to source how ‘classic’ is applied to film in the first half of the twentieth century. When did a certain film become a ‘classic’ and how do critical appraisals play a part in this? We do much the same exploring in literature, and some of our basic training may be carried over to the medium of film. Following on from your Introduction to Film Studies course in your first year, this elective aims to show you the development of popular cinema, or what we still refer to today as popular or mainstream cinema. The idea of popular cinema remains, for now, rooted in the West and in the Hollywood model but our work is to both explore and interrogate this and to find ways in which this industry refers to itself and the works that have influenced it. The elective looks at a variety of influential films that have helped cinema grow into its own lexicon, one that has been passed down through the twentieth century to us as modern cinemagoers. While we will recap some of the basics of audience reception theory and auteur theory covered in the first year course, we will also bring our study of classic cinema closer to the work we do in English Studies, namely criticism and cultural studies. The elective is intense and rigorous: 6 films, 2 documentaries and numerous critical essays form the material of the course. There are 2 short term assignments, 1 class test, regular class exercises and a final essay. Please consider this carefully and be sure whether your timetable is accommodating before you commit to this course. Also, if you do not watch the films then you will not be able to complete the elective. Intolerance (Dir. D.W. Griffith, 1916) The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (Dir. Robert Wiene, 1920) Sunrise (Dir. F.W. Murnau, 1927) Scarface (Dir. Howard Hawks, 1932) Modern Times (Dir. Charles Chaplin, 1936) Gone With the Wind (Dir. Victor Fleming, 1939) Additional readings will be made available. THE PASSION OF NEW BEGINNINGS [2nd semester] Riaan Oppelt Recent South African history is filled with senses of beginnings and endings, from the watershed moment of the first democratic elections in 1994 to the death of former president Nelson Mandela in 2013. Many Englishlanguage literary texts since 1994 had plenty of material to draw from in terms of fictionalizing both individual and communal experiences of change in South Africa. The constant regeneration of cultural, social, economic and political discourses in the country’s two decades under the title of “New” South Africa created, and still creates, extraordinary avenues for literary exploration of how individuals write themselves into an ever-shifting larger consciousness. With this in mind, the three texts selected for this course speak to an “opaqueness”1 of recent South 1 This term was used by renowned sociologist Peter Wagner in a series of seminar discussions presented at the University of Barcelona in 2012 and focused on the topic of South African modernity. 15 African modernity, a South Africa in which beginnings and endings can both trigger and cancel each other out. Niq Mhlongo’s After Tears (2007) offers a funny, poignant and innovative take on the driving forces of failure and success for many young South Africans in the twenty-first century, playing with the bildungsroman form but also displaying a slick documentary realism that will be analysed for its stylistic endeavour. Jacob Dlamini’s Native Nostalgia (2009) intriguingly revisits the past, that which supposedly ended, and offers an original perspective on township life during apartheid. The book challenges expectations of the term nostalgia and figures as part of what many South Africans, Dlamini argues, take with them into the “new.” Finally, Lily Herne’s Deadlands (2011) introduces familiar local settings to the event of the zombie apocalypse. The 2010 Soccer World Cup is Herne’s starting point: this much-anticipated global showpiece for South Africa becomes the site of the mysterious zombie calamity that marks the start of Herne’s Deadlands-quartet (2011-2014). In this course, we examine Deadlands as an early, exciting part of post-2010 literature aimed at a younger readership while simultaneously putting South Africa on the map as part of the universally popular “zombie scene” dealing with issues of mass industry, consumerism and regrowth. Jacob Dlamini. Native Nostalgia. Jacana, 2009. Nic Mhlongo. After Tears. Ohio University Press, 2011. Lily Herne. Deadlands. Much-in-Little, 2013. Students will be directed to selections from critical essays and articles by Jean Baudrillard, Rita Barnard and Jacob Dlamini. DECODING THE CITY: MODERNITY AND THE RISE OF THE DETECTIVE IN FICTION [2nd semester] Riaan Oppelt & Louise Green ‘The detective: The crime-hardened, realistic manhunter, never satisfied with pat answers, ended up fighting ghosts when he asked too many questions.’ Dashiel Hammett, The Dain Curse French writer and critic Charles Baudelaire spent much of his life walking the streets of Paris reflecting on the new forms of social life emerging in the modern city. In the city nearly everyone is a stranger, intriguing but also potentially threatening. Detective fiction emerges as a way of recording the enigmatic working of the modern industrializing city which appears to acquire a life and logic of its own. The detective is a privileged figure skilled in techniques for decoding the logic of the city, able to speak in its many languages. This course will begin by discussing Baudelaire and the figure of the stroller or flaneur, Baudelaire’s representation of the man of the city. Baudelaire was also fascinated with American writer Edgar Allen Poe, one of the initiators of the detective fiction genre. We will discuss some of his stories, and those of his British counterpart Conan Doyle before looking at the development of the genre into the twentieth century and beyond. Essay and short stories (will be provided): Baudelaire, C. “Painter of Modern Life”; Poe, E.A. “The Purloined Letter”; Conan Doyle, A. “The Adventure of the Speckled Band” Novels: Hammet, D. The Maltese Falcon. Vintage, 1989. Paretsky, S. Black List. Penguin, 2003. REPRESENTATIONS OF WITCHCRAFT IN SOUTH AFRICA [1st and 2nd semesters] Annel Pieterse Although belief in witchcraft features prominently in the lives of many South Africans, its representation in literary and public discourse in South Africa has not been given much scholarly attention. In this elective, I would like to explore the fluctuating representation of witchcraft in various cultural texts by South Africans, including: news media, music videos, photography, documentary, short stories and novels. In particular, I would like to focus on the relation between form and content, and explore the manner in which the supernatural is accommodated (or fails to be accommodated) by various forms. I will proceed from the hypothesis that while a belief in witchcraft and the supernatural has tended to be understood as a "traditional" form of knowledge, the given texts show it to be firmly embedded in a distinctly "modern", urban context. We will be exploring the various ways in which the supernatural is represented as interweaved with our daily contemporary South African reality. Beukes, Lauren. Zoo City. Jacana, 2010. Additional material will be provided. 16 THINKING NONFICTION: EXPERIMENTS IN WRITING REALITY [1st semester] Daniel Roux In his book Reality Hunger, David Shields makes a provocative assertion: “Today the most compelling creative energies seem directed at nonfiction”. The conventional frames for thinking about nonfiction – autobiography, journalism, history, and so on – are increasingly placed under pressure by new genre-bending experiments in documenting reality, and by the proliferation of information-age modalities that recalibrate and refine the relationship between representation and truth at a pace that often outstrips the ability of academic scholarship to keep up. This elective looks at two celebrated recent works of non-fiction that defy easy classification and work at the crossroads between genres. The first is Jonny Steinberg’s A Man of Good Hope, a chronicle of a Somalian boy’s journey to Cape Town and his growth into a man on the way. The second is George Packer’s The Unwinding, an economic and social analysis of contemporary America and its contracting middle class. In each case, we will look carefully at the narrative strategies employed by the writers and at how they negotiate the ethical dilemmas that arise when one writes about real people, places and events. A more practical outcome of the course is to think about what it means to chronicle reality today in complex, uneven and divided societies: there are many stories out there waiting to be written. This seminar is aimed at students who might one day want to rise to that challenge. Packer, George. The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America. Macmillan, 2013. Steinberg, Jonny. A Man of Good Hope. Jonathan Ball, 2014. USING LITERARY THEORY: MICHEL FOUCAULT [2nd semester] Daniel Roux This elective looks at a selection of theoretical writing by the French philosopher Michel Foucault. Theory is rarely taught at undergraduate level. This is because theory can be very challenging and abstruse, and also because it is conventional, in the discipline of English literary studies, to develop close reading skills before moving on to the more rarefied province of theoretical speculation. Nonetheless, this elective offers an introduction to some of the big questions that animate the study of literature: what is the social role of stories? How does literature relate to the real material world? How does literature help us to understand what it means to be a human being? The focus is on Foucault because he remains one of the most influential theorists in literary studies today. Understanding something about Foucault will give you purchase on the thinking of a wide range of contemporary critical positions, ranging from postcolonialism to queer theory to ecocriticism. We will draw on the texts that you study in the second year lecture syllabus for application examples. Selections from primary texts by Foucault will be made available in class. BITTERKOMIX: YOUTH ARE REVOLTING [1st semester] Louis Roux This course aims to explore the ideological construction of the Afrikaner and its downfall, as well as its postapartheid ‘identity crisis’, as presented in the revolutionary Bitterkomix series created by Anton Kannemeyer and Conrad Botes while they were students at Stellenbosch. Disillusioned by both their Afrikaner culture and the global culture of consumption, Botes, Kannemeyer et al. dissect the flaws and hypocrisies of the Afrikaner establishment, Rainbow Nation-ism and the contemporary neoliberal status quo through the use of satire, iconoclasm, sex, violence and tragedy in these comix. The course will follow Bitterkomix’s movement from the particular to the universal. Drawing on secondary readings by a selection of local and international scholars, the course will deal with themes of ideology, gender, race, history and power, and will prompt us to explore these concepts as they manifest in our own contexts. In addition to this theoretical approach, the course also demands creative engagement, and students will be required to create their own comix, which will be discussed and peerassessed in class. The course aims to create a greater understanding of systems of control and discipline, and how they can be undermined and negated by radical thought and radical creation. (Rated 18 for Sex, Violence, Language, Nudity, Prejudice and Blasphemy.) All readings will be provided. 17 INTERTEXTUALITY AND METAFICTION: NARRATIVE (RE)INVENTIONS [1st semester] Tilla Slabbert Stories (legends, myths, folktales) have been at the centre of human existence since time immemorial, in oral and written form. People invent stories to explicate and make sense of their environment, culture and society. As a “highly specialised and skilful form” (Gordimer), the short story provides a space for creative expression. In this elective we examine a selection of contemporary short stories from across the globe to explore the ways in which authors employ intertextuality and metafiction to comment on a variety of socio-political concerns, ranging from gender related issues, traumatic experiences, to anxieties about ecological catastrophe. Reading material will be supplied. “SOMETHING BETWIXT AND BETWEEN”: THE ART OF LIFE WRITING [2nd semester] Tilla Slabbert This course offers an introduction to the various forms of life writing. A range of examples from autobiographical, auto-ethnographical and biographical writings will be discussed to explore the complexities about telling a subject’s life story—working with memory and resources—to represent cultural self-images. Although the course proceeds from a historical overview, it focuses on a selection of (mostly contemporary) South African scholarly and popular life writings, for example: political (Nelson Mandela, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela); literary (Es’kia Mphahlele, Stephen Gray, Leon Rousseau, Antjie Krog); popular and celebrity (John Smit); and musical (Pat Hopkins). Reading material will be supplied. ‘FICTIONALISING’ THE SELF: WRITING STRATEGIES IN WOMEN’S AUTOBIOGRAPHY [1st semester] Lizelle Smit In this elective we will examine the writing strategies South African women used and still employ in the autobiographical genre to write the Self. This course primarily focuses on the subgenre of autobiography termed ‘autobiographical fiction’. Autobiographical fiction relies on omission, metaphor, fabrication, beautification, mythologising, sensationalism and misrepresentation to write multiple and versatile ‘selves’ to negotiate the complexity of ‘penning down’ a subject. As a point of departure we will launch into Melina Rorke’s autobiography which is arguably the first English autobiographical fiction written in South Africa. The focus then shifts to a contemporary author, Antjie Krog, championing the genre globally with her acclaimed ‘autobiographical’ works. Rorke, situated in politically turbulent nineteenth century South Africa (and the historical ‘Southern Rhodesia’), and Krog, detailing the struggles of negotiating identity in pre and post-apartheid South Africa, make for interesting comparative voices given the century dividing them. Consequently, we will compare the two women’s autobiographies to trace the development of the genre in South Africa and to consider the complexities and various ways of writing public and private selves. Krog, Antjie. A Change of Tongue. Random House, 2003. Rorke, Melina. Melina Rorke: Her Amazing Experiences in the Stormy Nineties of South African History – Told by Herself. Dassie Publishers, 1938. (Out of print: copies will be provided) Additional readings will be made available on SUNLearn. CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE CONTINENT: AFRICAN SHORT STORIES [1st semester] Tina Steiner This elective builds on the first-year short story syllabus and seeks to extend students’ understanding of the genre, with particular focus on close reading of narrative form. Participants will explore a range of short stories from East, West and North Africa that will be made available at the beginning of the semester. While we will concentrate on the detailed analysis of specific narratives, students will also gain an understanding of common thematic concerns in postcolonial Africa. Selected secondary readings on the genre will be made available on SUNLearn. In this course, students will write two essays and give one oral presentation. Prescribed readings will be made available. 18 MICHAEL ONDAATJE, LANGUAGE AND HOSPITALITY [1st and 2nd semesters] David Tyfield In this elective we will investigate Michael Ondaatje's novels, Coming Through Slaughter and The English Patient, in the context of the ethic of hospitality. The first half of the elective will look at Coming Through Slaughter and will give students the opportunity to come to grips with basic Saussurian semiotics. In the second half of the course we will read The English Patient and ask the question: What is “language’s constitutive, rather than merely referential relation to the world” (Mike Marais, “Violence, Postcolonial Fiction, and the Limits of Sympathy” 94)? This question naturally leads one to reflect on the ethical considerations of language, which will develop into a basic introduction to the ethic of hospitality. Ondaatje, Michael. Coming Through Slaughter. London: Bloomsbury, 2004. _____. The English Patient. London: Bloomsbury, 1992. Additional material will be supplied. 3. ASSESSMENT 3.1 CONTINUOUS ASSESSMENT This Department, like some other departments in the University, has adopted the system of continuous assessment (“deurlopende evaluering”). It is important that you realise the implications of this for you. As you will know, in most other departments your final mark (“prestasiepunt”) is a combination of a class mark (“klaspunt,” often still called by its outdated name “predikaat”) and an examination mark (“eksamenpunt”), carrying roughly the same weight. In these subjects, an examination mark of 50% entitles you to pass the year, provided that you have gained admission to the examination. A reasonable performance in the examination can thus cancel out a weak performance during the year. With continuous assessment, however, all your written work counts towards a single final mark which represents your performance for the course. There are no big, formal examinations: the end-of-year examinations are replaced by a test which counts no more than any other test of equal length. It follows that there is no opportunity to cancel out a weak class performance by a better performance in an examination. Please note that to pass the course, students must pass both the lecture component and the seminar component. That is, students must average at least 50% in the tests, and must also average at least 50% for the essay and elective mark, when these marks are combined. It is therefore vital that students attend all lectures and seminars, and read the setworks for each component. If you are not attending lectures AND seminars AND reading the setworks you will most likely fail the course. 3.2 PROGRESS MARK Progress marks are calculated and published at mid-year and before the final test, so students know where they stand. There is also no reassessment (“herevaluering”) as in most other subjects. The aim of this is to encourage and reward consistent work during the year rather than a last-minute spurt of cramming. It is most important, therefore, to attend all the classes and complete all the written assignments and all the tests. The Department has the right to fail students whose attendance is poor or who have not handed in all the required written work. See 3.4 and 3.5 below. Your Progress Mark has no official status, and is meant to be merely what it is—a gauge of your performance so far. 19 3.3 FINAL MARK Your final mark will be calculated according to a formula that takes into account test answers as well as work required for your seminars. The proportions are as follows: Tests Prepared work tested at official test times (6 test answers produced in the year – 1 at each mid-semester test and 2 at each end-of-semester test). First semester seminar Seminar mark (based on attendance at and contribution to the seminar and on a minimum of 2 written exercises). Final essay Second semester seminar Seminar mark (based on attendance at and contribution to the seminar and on a minimum of 2 written exercises). Final essay 50% 10% 15% 10% 15% Final marks will appear on the English 278 notice board on the second floor. Please do not telephone or ask the Departmental Officer for them. Please note: ALL appeals regarding first semester marks (regarding tests and seminars) should be dealt with before students depart on their mid-year break. Further, ALL appeals regarding ANY test or essay mark MUST be made within two weeks of the said mark having been announced. 3.4 “INCOMPLETE” The system of continuous assessment requires your preparation for and active participation in all aspects of the course. This means that at the very least you have to write all the official tests set in the course of the year and participate satisfactorily in seminars by doing the reading, attending the classes and submitting all the written tasks by the set deadline. Students who fail to meet these requirements will be regarded as not having completed the course and will be registered as “incomplete.” Lecture and seminar attendance is compulsory. Your seminar presenter keeps a record of attendance and you will be excused from class only if you provide a valid reason for your absence, with the relevant corroborating documentation. A valid reason would be medical incapacity or one of the other compassionate grounds specified by the University regulations (e.g., a death in the close family), as well as any formally arranged absence related to university business (in which case arrangements have to be made in advance). It is your responsibility to send an email explaining your absence to the seminar presenter no later than the day following your absence and to provide the relevant supporting documentation, for example the original medical certificate if you have been ill, within a week of your absence. If you miss a seminar and do not provide a valid excuse and supporting documentation, you will receive an official warning letter from the course presenter. If you miss two classes without a valid excuse and supporting documentation, you will be deemed “incomplete.” Even with the submission of supporting documentation, if you miss three meetings of your seminar group (in other words, a quarter of the course) the Department will consider you “incomplete” since your presence at and participation in the seminar group is a basic requirement for completing the module. In exceptional cases the Department will consider any formal appeal submitted. 20 3.5 MISSED WORK SEMINARS The submission of all written work by the set deadlines is a basic course requirement. Students who fail to do so will be regarded as “incomplete” and will not be able to complete the course. If you have a valid reason for being unable to submit the work by the deadline, it is your responsibility to notify your lecturer via email before the work is due, and to provide the relevant corroborating document, e.g. the original copy of the medical certificate if you have been ill. The work must then be submitted by the new deadline set by the lecturer. According to a Senate decision a student who fails to write the required number of exercises, essays and tests may be given a final mark of less than 50%, regardless of his/her arithmetical average. TESTS Please note: It is your responsibility to check test times (see “Test Dates” below) and venues before a scheduled test. You are reminded that the University regulations for test opportunities are not the same as those for examinations. The English Department uses the system of continuous assessment (“deurlopende evaluering”) for all its undergraduate courses, and thus students must write a test at the first opportunity. Only in the case of illness (for which a doctor’s certificate—the original certificate, not a photocopy—must be produced), or on one of the other compassionate grounds specified by the University regulations (e.g., a death in the close family) will the student be allowed to write at the supplementary (“siektetoets”) opportunity. The Department is also prepared to accommodate students who, according to the official test timetable, have test clashes—on the same day and at the same time—with that of another subject, but this must be arranged with the Department well in advance, and proof must be provided. Under the new University regulations only one other test time is provided, and students who have applied for and have been granted permission will have to write at that time. It is the responsibility of students who miss the first test date to report as soon as possible after their return to the campus to the Administrative Officer (Ms Carol Christians, Room 581), in order to register for the supplementary test date. You will only be allowed to write the supplementary test if your name appears on the list of students registered for the test—all other students will be denied access to the test venue. No further opportunities to write will be provided. Final year students please note: Writing the last supplementary test (in November) will mean that you will only be able to graduate in March of the following year. The Department may set open-book questions in tests, which students will be unable to answer unless they have a copy of the relevant text with them. No sharing will be allowed. 4. TESTS 4.1 TEST MARKS In exceptional cases, where a student is convinced that a test answer has been seriously underrated, the procedure of appeal, which must be initiated no more than one week after the marks become available, is as follows: Make a note of the marker’s name written on the cover of the script (consult the Departmental Officer if the name or initials are unclear). Make an appointment with the marker to discuss why the mark was given. If the student wishes to pursue the matter further, the script is taken by the marker to the Course Coordinator who will assign a second marker (another member of staff) to re-evaluate the script. 21 It should be stressed that students should not abuse this procedure and should resort to it only when they are convinced that they have a legitimate case for re-evaluation. Their test script must have received a mark that is at least 10% less than their pre-test progress mark, and the student must request a remark within two weeks of the publication of the test results. 4.2 TEST DATES APRIL Test Sat 2 April 9:00 Supplementary Wed 13 April 17:30 JUNE Test Mon 23 May 14:00 Supplementary Thu 9 June 9:00 SEPTEMBER Test Thu 15 September 17:30 Supplementary Wed 12 October 17:30 NOVEMBER Test Tue 1 November 9:00 Supplementary Fri 18 November 9:00 DEAN’S NOTICE ON TEST DATES Notices with dates, times and venues will be available on the notice board and on SUNLearn two weeks prior to tests. Students will not be allowed to choose between the two test sessions in a module. The first test session in a module will be compulsory for all students. A student who for medical reasons certified by a physician is unable to take the first test in a module will be allowed to take the test during the second examination session in that module. The student will be required to complete an official declaration on a specified form to declare that he/she had indeed been ill. With the exception of a Dean’s Concession Examination for final-year students who qualify for such a test, no further examinations will follow the second test sessions. See Missed Work (3.5 above). 5. ESSAYS AND ASSIGNMENTS In addition to written assignments set by your seminar lecturer in the course of each semester you will be required to write one essay of 2000-2500 words. All work must be handed in on the due date; late submissions will be penalised. Students who fail to submit ALL of the required work will be regarded as “incomplete”, which in effect means they cannot pass the course. No outstanding work will be accepted after the end-of-semester test. Consult the Department’s “Guide to Writing Essays,” available from the Departmental Officer. The rules and conventions spelt out in this guide must be followed. Essays which do not observe these rules may be returned for rewriting. 5.1 SUBMISSION OF WRITTEN WORK Please note the following rules with regard to submitting written assignments and essays: 22 Students must make and keep a copy of any written work they submit. Unless otherwise stated, work must be handed directly to the lecturer in the seminar class on the due date. A signed and dated copy of the Department’s declaration on plagiarism (see 5.3) must accompany your submission. You should also submit your work to Turnitin. Dual submission (hard copy and Turnitin, or email and Turnitin) is always necessary to ensure that work does not go astray. Late essays must be handed to your lecturer in person or emailed. They must not be handed to the Departmental Officer or left in post boxes. 5.2 LATE SUBMISSIONS You are reminded that ALL required written work must be handed in for your record to be complete. If you fail to hand in all of your assignments and essays, you will be regarded as “Incomplete” and you will fail the course. Even if an assignment or essay is so late that it will earn 0%, it must be handed in. No work will be accepted after the end-of-semester test. NB: Late submissions have to be genuine and worthwhile attempts at the topic. A late penalty of 5% of the essay mark per day will be applied from the due date of the assignment or essay. It is the student’s responsibility to ensure that lecturers are alerted to and aware of the submission of late work. 5.3 PLAGIARISM Plagiarism refers to any attempt by a student to pass off someone else’s work as his or her own; it may for example be the work of a fellow student, a friend or relative, or a critic whose work you have found in the library or on the internet. At all times distinguish between the ideas of those whose work you have read and your own comments based on their ideas. The safest, the fairest, way to acknowledge your indebtedness is to use established conventions of documentation and referencing such as the MLA Style. Please consult the “Guide to Writing Essays” (available on the Department’s website) in order to check how to reference properly in MLA style. Please note that plagiarism includes the use of notes or critical material (from the internet or elsewhere) which is memorised and repeated (often word for word) in test answers, without any attempt to acknowledge indebtedness to the source (e.g. SparkNotes). Depending on the extent and seriousness of the offence, such answers will fail, and are likely to receive a mark of 0%. The procedures prescribed by the university for cases of plagiarism will be followed. Plagiarism is a most serious academic offence, which negates everything we try to encourage in our students in this department. If you are unsure of what is meant by “plagiarism,” consult your seminar lecturer. Do not risk having an essay returned with “0” as your mark – or even your exclusion from the course. A signed and dated copy of the Department’s declaration on plagiarism must accompany your essay. Copies of the statement are available from your lecturer. It is also included in the “Guide to Writing Essays” and is available on the Department’s website. Students are expected to familiarise themselves with the Faculty policy on plagiarism, which spells out the different categories and procedures to be followed in dealing with cases of plagiarism. Any attempt to represent someone else’s work as your own will be regarded as a most serious offence and (depending on the severity of the offence) may result in your exclusion from the course and from the university. 23 6. POSTGRADUATE COURSES During the December-January vacation you will no doubt be finalising your course choices for your third year. We trust that your majors will include English 318 and 348. Prospectuses giving details of the postgraduate courses offered by the Department are available from the Departmental Officer’s office. As you will see, we offer a wide range of exciting courses in the different postgraduate programme options. We hope this will encourage you to start planning ahead now for what you might be considering after you have completed your undergraduate courses. Our graduates have found that a background in English Studies prepares them for a variety of career options, so do keep this in mind when you are choosing. If you would like to have any further information, please ask Dr de Villiers. 7. BURSARIES Do bear in mind that there are various bursaries available for continued study in the English Department. Consult Calendar 2015, Part 2. For further inquiries contact Ms F Niemann at the University Administration (Tel 808 4627; email fn@sun.ac.za). Note especially the Babette Taute bursaries which offer generous amounts (up to as much as R7000) for fees etc., as well as book grants for buying setworks for students going into their third year. Also note the Winnifred Wilson bursary. VAN SCHAIK’S ANNUAL BOOK PRIZES Three prizes are awarded each year to the student who achieves the highest overall marks for the year (i.e. only third-year students who have completed both semesters will be eligible for the prize): English 178: R200 English 278: R300 English 318/348: R500 24 8. STAFF OF THE DEPARTMENT Please note that some staff members are on leave in 2015. The departmental telephone number is 808-2040 (Departmental Secretary) and each member of staff can be dialled directly on his/her own number. ACADEMIC STAFF Bangeni, NJ (Dr) De Villiers, DW (Dr) Ellis, J (Dr) Green, L (Prof) Jones, M (Dr) Mbao, W (Dr) Murray, S (Prof) Musila, G (Prof) Oppelt, RN (Dr) Roux, D (Dr) Sanger, N (Dr) Slabbert, M (Dr) Steiner, T (Prof) Viljoen, SC (Prof) e-mail Ext Room njban dawiddv jellis lagreen meganj wmbao samurray gmusila roppelt droux TBA mslabbert tsteiner scv 2399 2043 2227 3102 2048 2042 2044 2046 2049 2053 TBA 3652 3653 2061 585 583 588 (on study leave) 564 572 582 573 586 (on study leave) 580 570 TBA 578 566 575 2605 562 PROFESSORS EMERITA/EMERITUS Prof AH Gagiano Prof L de Kock ahg leondk PROFESSORS AND LECTURERS EXTRAORDINAIRE Prof Rita Barnard (University of Pennsylvania) Prof Maria Olaussen (Linnaeus University) Prof Gabeba Baderoon (Pennsylvania State University) Prof Okello Ogwang (Makerere University) ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF Colette Knoetze (Mrs) colettek (Senior Departmental Officer) 2040 574 Johanita Passerini (Mrs) (Administrative Officer) 2051 581 johanitap 25