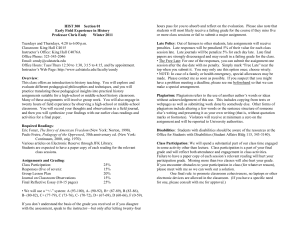

syllabus - University of Puget Sound

advertisement

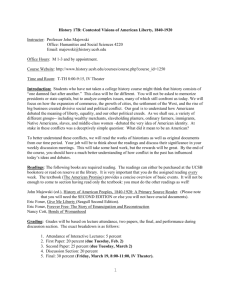

Nancy K. Bristow Office: Wyatt 140 Phone: 879-3173 Email: nbristow@ups.edu Office Hours: M/W/F 9:00-10:50 and by appointment American Experiences II: 1877 to the Present Spring 2016 T his course is designed to introduce you to some of the central topics and issues in American history from 1877 to the present while also providing you with the opportunity to gain a working understanding of the historical and humanistic perspectives embodied in the methods of the historian. The course adopts a broad conception of history, and will touch on aspects of the political, social, cultural, economic, diplomatic and military history of the nation. It will also explore the diversity of the American past, incorporating into our investigations the intersecting complexity and range of ethnic, racial and gender groups as well as social and economic classes that have peopled that history. This course will attempt to grant all Americans their roles as historical actors, exploring the multiple influences involved in shaping the United States. While this will make for a complicated picture of the American past, it is only with that complexity intact that we can hope to understand this nation’s history. The period we will be studying is a dynamic one, filled with dramatic change for the United States. A rural nation devoted to agriculture in 1877, the United States was nevertheless already involved in a process of industrialization and urbanization that was irreversible. Based in ideals of freedom and equality, the nation continued to reflect vast disparities in rights and opportunities based in social categories such as (but not limited to) race, class, gender, sexuality and religion. Purportedly isolationist in 1877, by the turn of the twentieth century the United States was increasingly engaged in actions overseas, another trend that would persist with seeming inevitability. Confronted with a changing nation and a changing world, Americans in the period since 1877 have wrestled with insistent issues of identity. Who, they have asked, is an American? What are the shared values that can be understood to define this American? What rights does this identity impart? What responsibilities? Over the course of this semester we will explore the changes that have taken place in this nation since 1877, as well as the ways in which Americans have wrestled with those changes in their debates over national identity. While this course will acquaint you with the general outline of American history, it will also be important for “History…does not refer merely to the past…history is literally each of you to develop your own skills as an historian. present in all that we do.” When we study history, we of necessity study --James Baldwin interpretations as well. While historians seek to write and speak only what they understand to be true, each person studying history carries with them their own assumptions and their own history. In this course we will work to understand the various interpretations placed on the past, as well as the assumptions that frame our own interpretations--assumptions based in our individual identities and shaped by the broader structures within which our lives take shape. Our goal will be to use these explorations to compile an understanding of the past on its own terms, even as we understand the relationship between that past and the world within which we live today. In order for this process to be successful, each of you will need to approach the class as an active participant. Consider yourself an integral part of the class. Each of you has much to contribute and the class will benefit to the extent that each of you approaches it with a sense of responsibility for our shared work this semester. 2 REQUIRED READING: In an effort to introduce you to a wide range of historical sources, the readings for this course are both extensive and wide-ranging. The books listed below will be required reading during the course, and are available at the bookstore and on reserve at the library. There are also several sources that we will access through a course packet, available only through the bookstore, and an occasional source on our Moodle site. Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty, vol. 2 – Brief Edition (Fourth Edition – 2014) Eric Foner, Voices of Freedom: A Documentary History, vol. 2 (Fourth Edition - 2014) Douglas Cazaux Sackman, Wild Men: Ishi and Kroeber in the Wilderness of Modern America (2010) Robert S. McElvaine, Down and Out in the Great Depression: Letters from the Forgotten Man (25th Anniversary Edition, 2008) Gilbert King, Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America (2012) Philip Caputo, A Rumor of War (1977, 1996) Peter Orner, Underground America: Narratives of Undocumented Lives (2008) Ta-Nehesi Coates, Between the World and Me (2015) History 153, Course Reading Packet MOODLE: Moodle is an online system that provides courses with a web presence. This semester, we’ll be using Moodle in History 153. Specifically, our Moodle site provides a great deal of information about the course—the course syllabus, assignments, some of our readings, and various handouts, for instance. If you have any problems using Moodle, just come by my office and I’ll help get you started. COURSE OBJECTIVES: Students in this course will: gain an understanding of the historical and Let a thousand historical flowers bloom. History is humanistic perspectives. never a closed book or a final verdict. It is forever in gain an overview knowledge of American history the making. in the period from 1877 to the present, and in particular of the experiences and values of the --Arthur M. Schlesinger, 2007 diverse peoples that make up the United States. learn the methods employed by historians, in particular the critical reading of both primary and secondary sources. polish their skills in critical thinking, oral and written communication and collaborative learning. 3 WRITING ASSIGNMENTS You have two kinds of writing assignments this semester—short exploratory exercises and longer, fully developed essays. The exercises give you the chance to do some indepth thinking in anticipation of upcoming work—class meetings, debates, and larger writing assignments, for instance. The more comprehensive essays will give you the opportunity to work as historians, employing investigative, analytical, and integrative techniques in the development and defense of your own ideas about significant historical questions. Below are brief descriptions of the assignments in the order in which they will be due. Fuller explanations for the three longer essays will be distributed and discussed in class. The page lengths listed below are not limits, but serve only to give you an idea of the scale of paper I am expecting. Exercises and essays should be typed, double-spaced, and cited using Chicago Manual of Style footnotes or endnotes. Exploratory Exercise #1: Reading Primary Sources Critically (2 paragraphs) Your job in this memo is to select any one of the primary sources included in the reading for February 5 and to write two paragraphs about it. In the first, suggest one problem the historian needs to take into account as they approach the source, for instance one issue that would lead you to challenge it as a statement of simple fact. In the second, explain one insight you nevertheless gained by thinking critically about the source. You may even find that the source’s limitation is also the source of this unintended insight. Due in class on Friday, February 5 Essay #1: The United States at the Turn of the Century: Defining “American” (3-4 pages) A nation of immigrants living on land they took through armed struggle, the people of the United States have long contested the meaning of the term “American.” This first paper asks you to analyze how one person or group conceptualized “the American” in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. How, in other words, did this person or group define who was American? What did the term mean to them? What qualities or beliefs did they associate with the term? There will be many ways to approach this paper, and we will discuss some of the options in class to prepare you for the assignment. You will not need to do any outside research for this paper. Due in class on Wednesday, February 17 Exploratory Exercise #2: The History of Tacoma and the University of Puget Sound As our readings and discussions for February 5 make clear, our local history is not isolated from the dynamics of the nation’s history, but co-exists with influence running both directions. In turn, since 1889 the College/University of Puget Sound has had its own history, also operating in and interacting with these broader contexts. In order to help us study these interactions, each of you will be responsible for making one entry to a class timeline, providing us with one primary source and commentary about our local history and its relationship to the national story we are studying. These entries may also serve as inspiration for final projects! Fuller details on this assignment will be distributed in class. Due in class on individual assigned days—you will sign up for these in class. Essay #2: The Great Depression and American Life In the middle weeks of the semester we will spend significant time discussing how to work with multiple sources to develop your thinking about the past. For your second paper you will combine your critical reading of Down and Out in the Great Depression with at least one other primary source in order to develop a response to that book and the ideas it suggests about life during that difficult era. Due in class on Friday, March 4 4 Exploratory Exercise #3: Final Project Research Plan To ensure you are moving forward with your final research project, and to give me a chance to check in with you, this exercise asks you to lay out your plans for the project. You should do four things in the exercise. First, suggest the overall focus of the project. What historical issue or trend will the paper engage? Second, provide a one-paragraph annotation of the secondary source you will test with your primary source work, including the key argument you will consider. Third, suggest the primary source(s) you will use to conduct the local history or family part of your exploration, and the initial findings you have so far. (Does your research confirm or challenge your secondary source? How so?) Finally, suggest one digital addition you plan to make to the paper. Due in class on Wednesday, April 6 Essay #3: Family History or Local History Research Project (roughly 7 pages) This assignment asks you to connect one of the broader currents of United States history that we have been studying with either your family or the local history of the university or Tacoma. You will begin by deciding on some aspect of the history we have studied you are interested in exploring more fully. Then you will locate a secondary source on that subject to supplement what you know about the issues historians wrestle with regarding this topic. Then, using this as the basis for your “national story,” you will collect primary sources—on either your family or the local history of Puget Sound or Tacoma—that will allow you to test the thesis of your secondary source and to explore the resonance or dissonance between the national dynamics and those of either your family or our local context. This means that you should expect to research both the experiences of your family (or a particular family member), the University of Puget Sound, or the Tacoma region, and the broader national context for the particular issue or topic you are exploring. Finally, these will be turned in as Digital Essays, so you will need to think about how you will integrate images and sound clips into the paper. The toughest part of this assignment will be putting all of these different kinds of sources into conversation with one another. Due in class on Wednesday, May 4 Grading Standards for Writing Assignments A paper that receives a grade lower than “C” does not meet the standards of this course. Typically a “D” or “F” paper does not respond adequately to the assignment, is insufficiently developed, is marred by frequent errors, unclear writing, confusing organization, or some combination of these problems. A typical “C” paper has a good grasp of the material on which it is based and adequately responds to the assignment, reflecting a solid understanding, a strong thesis, and meaningful insights. Yet such a paper may provide a less-than-thorough defense of the student’s ideas, or may suffer from problems in presentation such as frequent errors, unclear writing, or confusing organization. A typical “B” paper is very good work that contains significant insights that demonstrate that the student has engaged in serious thinking and has developed an important and imaginative thesis as a result. A “B” paper also includes strong development of the main ideas of the paper, including substantial and well-explicated evidence. These papers are generally effective in their presentation as well. A typical “A” paper is exceptional. Not only does an “A” paper include all of the strengths of a “B” paper, but it also has an exceptionally perceptive and original central argument that is cogently argued and supported by a very impressively chosen and developed variety of specific examples drawn from a range of sources. An “A” paper also succeeds in suggesting the importance of its subject and of its findings. 5 CLASS PARTICIPATION: Discussion is an important part of this course. While the course will include some brief lectures, it is in class discussions that we will have the opportunity to pursue together answers to the multitude of questions the readings will raise. Working together, we have the opportunity to learn from one another, to consider viewpoints different from our own, and to build on one another’s ideas. Keep in mind that attendance and contributions to discussions will make up an important part of your grade. Also remember that there are many ways to contribute to a discussion. Asking questions, offering ideas, providing evidence for the ideas of others, and synthesizing recent points are all ways of making a significant contribution to the on-going conversation. The following suggestions will help to make our discussions as fruitful as possible: Prepare for class: This includes not only reading all assignments before class, but thinking about them as well. Be sure to read and think about the discussion questions included in the syllabus under “prep” for each class day. It is often useful to write down a few thoughts and questions before class. This not only forces you to think critically about what you are reading, but will often make it easier for you to speak up during the discussion. Attend class: Unless you are in class, the rest of us cannot benefit from your ideas, and you will miss the opportunity to benefit from the ideas of your classmates. Further, lectures and films offer you information and context to help you understand your readings, and should not be missed. Participate in discussions: We can only know your ideas if you express them. Twenty-some minds are always going to be better than just one. For this reason, we will all benefit from this course to the degree to which each of you participates in our discussions. Each of you has a great deal to contribute to the class, and each of you should share that potential with the other class members. Listen to your classmates: The best discussions are not wars of words, but are a cooperative effort to understand the issues and questions before us. Listen to one another, and build on the conversation. While we will often disagree with one another, you should always be sure to pay attention to the ongoing discussion, and to treat your classmates and their ideas with the respect they deserve. Remember this is a learning community, and do what you can to invite others to see themselves as full and welcomed members. Grading Standards for Class Participation: A student who receives a grade lower than “C” is consistently unprepared, unwilling to participate, refuses to engage with others, often seems distracted from the discussion, or is too frequently absent. A student who receives a “C” for discussion typically attends every class and listens attentively, but rarely participates in discussion. Other “C” discussants would earn a higher grade, but are too frequently absent from class, or may not listen openly to the ideas and suggestions of others. A student who receives a “B” for his or her participation typically has completed all the reading assignments on time, and makes important contributions to our discussions. This student may tend to wait for others to raise interesting issues, rather than initiating discussion. Other “B” discussants are courteous and articulate but do not listen to other students, offering their ideas without reference to the direction of the discussion. Still others may have a great deal to contribute, but participate only sporadically, or may not regularly connect their contributions to particular texts or specific examples. A student who receives an “A” for his or her participation typically comes to every class with questions and ideas about the readings already in mind. He or she engages other students and the instructor in discussion of their ideas as well as his or her own. This student is under no obligation to change their point of view, yet listens to and respects the opinions of others. This student, in other words, takes part in an exchange of ideas, and does so on a regular basis. This student also makes use of specific texts and examples during the discussion. 6 QUIZZES: You will take five quizzes over the course of the semester, on February 10, February 24, March 9, April 8, and April 29. These quizzes will test your command of the historical information offered in the various readings for the course, including the textbook, and will also test your understanding of that information. Each quiz will consider course materials covered since the previous quiz, including the readings for the day on which the new quiz is given. The format for the quizzes will range from multiple choice and true-false questions to term definitions and short-answer questions. Missed quizzes can be made up, but the rules surrounding these make-ups are firm. In the case of unavoidable emergencies and illness with a proper medical excuse, you may take make-up quizzes without penalty. Similarly, if arrangements are made in advance, you may also take a make-up quiz in the case of unavoidable school-related activities without penalty. No other make-up quizzes are permitted. POLICIES: Digital Assignments: This course incorporates various online software and other technologies. Some technologies require you to either create an account on an external site or develop assignment content using them. The content, as well as your name/username or other personally identifying information may be publicly available as a result. While the purpose of these assignments is to engage with technology as a means for representing the content we are discovering in our work, please see me if you have concerns about sharing your account, name or other content you would create in these technologies. We can either establish an alias for your use, or have you complete an alternative assignment. 48 Hour Rule: In this course, we will operate according to my “48 hour rule.” This means that you can turn in one paper or memo up to 48 hours late without penalty or explanation. Beyond this, though, late papers or memos will be accepted only in cases of illness or emergency, or when prior arrangements have been made, and will generally be penalized except in cases of illness or emergency. Course Completion: You must complete all writing assignments in order to pass this class. Those missing any of the writing assignments will receive a WF for the course. Similarly, too many unexcused absences will also result in withdrawal from the course. Academic Honesty: It is assumed that all of you will conform to the rules of academic honesty. I should warn you that plagiarism and any other form of academic dishonesty will be dealt with severely in this course. Plagiarizing in a paper or cheating on a quiz will be reported to the university, will result in an automatic F on that assignment and potentially in the course, and may lead to more substantial university-level penalties. Because academic dishonesty is such an egregious offense, the penalty is not negotiable. As a member of this academic community, your integrity and honesty are assumed and valued. Our trust in one another is an essential basis for our work together. A breach of this trust is an affront to your colleagues, your instructor, and to the integrity of this institution, and so will be treated harshly. If you have any questions about these rules, too, know that I am anxious to help clarify them. Accessibility and Accommodations If you have a physical, psychological, medical or learning disability that may impact your course work, please contact Peggy Perno, Director of the Office of Accessibility and Accommodations, 105 Howarth, 253.879.3395. She will determine with you what accommodations are necessary and appropriate. All information and documentation is confidential. 7 Bereavement: We all hope this policy will not come into play, but if this should occur, the University of Puget Sound recognizes that a time of bereavement can be difficult. Therefore, the university provides a Student Bereavement Policy for students facing the loss of a family member, which this course follows. Students are normally eligible for, and I would of course grant, three consecutive weekdays of excused absences, without penalty, for the death of a family member, including parent, grandparent, sibling, or persons living in the same household. If you need additional days, you should let me know, and also request additional bereavement leave from the Dean of Students or the Dean’s designee. In the event of the death of another family member or friend not explicitly included within this policy, know that you can petition for grief absence through the Dean of Students’ office for approval, and I am very open to granting it for the course as well. To request bereavement leave, a student must notify the Dean of Students’ office by email, phone, or in person about the death of the family member. If you need any help with this process, please just ask and I will supply whatever support I can. Other Policies: For any policy issue not covered here, I follow the rules set down in The Logger, the university’s academic handbook. You have responsibility to be familiar with the handbook and the policies it contains. You can access it on the university website at: http://www.pugetsound.edu/student-life/personal-safety/student-handbook/academichandbook/ GRADING SCALE: A+: B+: C+: D+: F: 97-100 87-89 77-79 67-69 below 60 A: B: C: D: 93-96 83-86 73-76 63-66 A-: B-: C-: D-: 90-92 80-82 70-72 60-62 FINAL GRADES: Your final grade in this course will be based on the following weighting of the course requirements: 2.5% 12.5% 5% 15% 2.5% 22.5% 20% 15% Exercise #1: Working with Primary Sources (due in class on February 5) Essay #1: Defining “American” (due in class on February 17) Exercise #2: Tacoma / Puget Sound Timeline Digital Contribution (individual due dates) Essay #2: The New Deal (due in class on March 4) Exercise #3: Planning the Research Project (due in class on April 6) Essay #3: Final Research Project (due in class on May 4) Quizzes (Feb. 10, Feb. 24, March 9, April 8, April 29) Attendance and participation in discussions 8 SCHEDULE OF READINGS AND ASSIGNMENTS Week #1 (W) January 20 Introductions: The Course and the Historical Perspective WELCOME TO THE COURSE!! (F) January 22 Introductions: History, Reconstruction, and Ourselves as Historians READING: Moodle: Cartoons by Thomas Nast Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty! An American History, ch. 15 PREP: In our first class we talked about how easily we can read sources from our own time because we know their context. Today we will turn our attention to the past, thinking about why and how historians do their work, and what that means for each of us as we begin our explorations of earlier worlds and lives. Begin your preparation with the three political cartoons by Thomas Nast. Note the transition in his depiction of freed African Americans between the second and third cartoons. How should we make sense of this? In order to understand the meaning of these cartoons—both in their own time and for our understandings of the era of Reconstruction—we will need to look carefully at this historical period. To do this, complete the other reading for today. What was at stake during Reconstruction? Whose interests were served at different stages? Who were the ultimate winners and losers? Now return to the cartoons. Think first about Nast’s intended meaning with each cartoon. What positions on Reconstruction did he intend to encourage in his readers? How can they help us understand the history of Reconstruction? Week #2 (M) January 25 No Class Today I will be participating in the interviews of finalists for the university presidency today. Use today to read ahead. There is significant reading for Wednesday. 9 (W) January 27 Indian Wars? READING: Course packet, 3-5 o “Reading Secondary Sources” o “A Fight with the Hostiles,” New York Times, 30 December 1890 o Dawes Severalty Act, 1887 Douglas C. Sackman, Ishi and Kroeber in the Wilderness of Modern America, Prologue, Chapter 1 and 2, and Afterword PREP: Begin by looking at the two primary sources for today. Using the instructions on “How to Read Primary Sources” distributed in class on Friday, think about the insights we can gain by reading them critically. For instance, how did they portray Native Americans? Their own culture? Use these documents as context for thinking about the relationship between Native Americans and United States. Today we begin reading a source written by an historian, Douglas Sackman, a member of the Puget Sound faculty. His book will give us a chance to consider the role and responsibilities of the historian even as it opens up our explorations of many different subjects and issues in the history of the United States. For today, begin by considering how Sackman sets up his exploration of Ishi and his worlds. How does Sackman conceptualize the history of Ishi and his people? Why did he begin his book where he does? What are the “three worlds” of the Yahi he explores in the first chapter? What, in turn, is Sackman arguing in this chapter? How do you know? Do find his ideas compelling? Why or why not? Now read Sackman’s “Afterword.” Does this provide any additional insights into Sackman’s imagining of the historian’s work? (F) January 29 The Gilded Age: Introducing Industrialization and its Ideology READING: Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty! An American History, ch. 16 Eric Foner, Voices of Freedom, 28-35 o Andrew Carnegie, The Gospel of Wealth o William Graham Sumner, On Social Darwinism Course Packet: 6-10 o Andrew Carnegie, “A Talk to Young Men” PREP: Today we will continue to talk about the careful and critical reading of primary sources, and will also turn to the emergence of industrialization as an economic, political, social and cultural phenomenon. How do the sources by Carnegie and Sumner reflect particular ways of understanding the world? What assumptions and values can we discern in their writings? How would you compare their worldview with that of Ishi and his people? Week #3 (M) February 1 Industrialization and the Laborers’ Alternatives: A Labor Conference READING: Eric Foner, Voices of Freedom, 36-37 o “A Second Declaration of Independence” Course Packet, 11-25, 127-128 o Documents on the Pullman Strike o Upton Sinclair, The Jungle, excerpt Visit the Historical New York Times, available through the library’s website, and read at least 3 articles relevant to your preparation for today’s labor conference. PREP: We will assign responsibilities for today’s class ahead of time. Then follow the preparation instructions for your group. 10 (W) February 3 Politics: From the Gilded Age to the Populists READING: Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty! An American History, ch. 17 Eric Foner, Voices of Freedom, 38-53 o Henry George, Progress and Poverty o Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward o Walter Rauschenbusch, Christianizing the Social Order o The Populist Platform PREP: Does the term “gilded age” fit this period? Why did so much reform energy take place outside the mainstream political process? (F) February 5 Immigration, Nativism and the New Imperialism READING: Moodle: Jean Pfaelzer, Driven Out: The Forgotten War against Chinese Americans, Introduction Course Packet, 1-2, 26-33 o “Grand Mass Meeting” o The Chinese Exclusion Act o Albert Beveridge, “The March of the Flag” Eric Foner, Voices of Freedom, 66-72 o Josiah Strong, Our Country o Emilio Aguinaldo on American Imperialism in the Philippines o Rudyard Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden” PREP: Today we will have the chance to see that our local history is not isolated from the broader national landscape of issues and tensions as we explore the expulsion of Chinese and Chinese-Americans by white Tacomans in 1885 as one part of the story of nativism and imperialism in the late nineteenth century. Our conversations will be particularly sophisticated today, too, because you will have completed your first memo about one of today’s primary sources. Today’s discussion will launch our semester-long Tacoma /Puget Sound history project, a digital project in which you will all play a role! DUE: Your FIRST EXERCISE is due in class TODAY! Week #4 (M) February 8 Racial Politics: Violence, Resistance and Accommodation READING: Eric Foner, Voices of Freedom, 53-63 o John Marshall Harlan, Dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson o Ida B. Wells, Crusade for Justice Course Packet, 34-45 Booker T. Washington, Address to the Atlanta Exposition W. E. B. Du Bois, “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others” Moodle: Majority Opinion, Plessy v. Ferguson PREP: Though Justice Harlan dissented in Plessy v. Ferguson, might his opinion help us understand the context within which the majority could accept segregation as constitutional? What did his view share with that of the majority? How in turn did Wells, Washington and Du Bois, three African American leaders, conceptualize the situation of African Americans? What strategies did each propose to solve the racial 11 crisis? How do you explain their differences of opinion? To whom might each have appealed? Why? (Think carefully about historical context.) (W) February 10 Ishi and the Wildness of a Modernizing Nation READING: Douglas Sackman, Wild Men, Chapters Three, Four and Five PREP: As you think about Ishi’s confrontation with “modern” American culture, how would you compare the culture of the Yahi with that culture? Can you find any similarities? What are the most significant differences? Be sure to think, in particular, about the differences in the ways the Yahi and modernizing Americans understood knowledge itself. How did this affect their interactions? Finally, what does Sackman mean when he suggests of Ishi, “He’d been living in a world shaped by the consequences of the image of Indians that whites held in their heads”? DUE: You will take your FIRST QUIZ today. (F) February 12 Defining “Modern” / Defining Progressivism READING: Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty! ch. 18 Eric Foner, Voices of Freedom, 73-94, 98-99, 114-118 o Manuel Gamio on a Mexican-American Family and American Freedom o Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Women and Economics o John A. Ryan, “A Living Wage” o Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, “The Free Speech Fight at Spokane” o Margaret Sanger, “Free Motherhood” o Carlos Montezuma, “What Indians Must Do” o R. G. Ashley on Unions and the “Cause of Liberty” o Randolph Bourne, “Trans-National America” Course Packet: 46-71: Gary Gerstle, “Theodore Roosevelt and the Divided Character of American Nationalism” PREP: We’ll start by figuring out what historians mean by the term “Progressivism.” As you read through the primary sources, what values, goals, and methods might seem to join many of these reformers? How, in turn, does Gerstle’s argument about Roosevelt frame your understanding of Progressivism? Week #5 12 (M) February 15 Ishi, Kroeber and Sackman: A Visit with the Author READING: Douglas Sackman, Wild Men, Chapters Seven, Eight and Epilogue, and review Afterword PREP: Today we will have the opportunity to discuss Wild Men with Professor Sackman, who will be joining our class meeting. In order to prepare, then, write down at least one passage you would like him to discuss with you, and one question that the text has left you with. (W) February 17 TUTORIAL FOR TACOMA / PUGET SOUND DIGITAL PROJECT PREP: No new reading for today. To prepare for class, complete your first paper. In class we will have a tutorial about the digital project we will be working on together over the next several weeks. DUE: Your FIRST paper is due in class TODAY! (F) February 19 United States and the World: World War READING: Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty, ch. 19 Eric Foner, Voices of Freedom, 100-113, 118-121, 125-130 o Woodrow Wilson, Declaration of War speech o Mao Zedong, Critiques of the Versailles Peace Conference o Carrie Chapman Catt, “Address to Congress on Women’s Suffrage” o Eugene V. Debs, “Speech to the Jury” o Rubie Bond, “The Great Migration” o John A. Fitch, “The Closed Shop” PREP: Was American involvement in World War I similar to or different from the nation’s earlier imperialistic engagements? Why? How did Wilson depict American goals? American identity itself? How, in turn, did the growing international role affect domestic politics. Was war, as the historian Richard Hofstadter once argued, the “nemesis” of reform? Week #6 (M) February 22 The 1920s: “Modern Times” or “Progress and Nostalgia”? READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, p. 609-631 Foner, Voices of Freedom, 122-124, 131-157 o Marcus Garvey, Africa for the Africans o Andre Siegfried, on the “New Society” 13 o American Civil Liberties Union on the Fight for Civil Liberties o Bartolomeo Vanzetti’s Last Statement in Court o Congress Debates Immigration o Meyer v. Nebraska, Opinion of the Court o Alain Locke, The New Negro o Elsie Hill and Florence Kelley Debate the ERA PREP: What does the textbook argue about the nature of the 1920s? Put another way, what is the thesis of this chapter? Do the primary sources support this interpretation? Some historians have suggested the 19320s are the first “modern” decade. Others suggest it had a strong streak of nostalgia for an imagined past. Can you imagine any alternative characterizations for this decade? (W) February 24 The Depression Hits the American People READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, pp. 631-638 and ch. 21 Robert S. McElvaine, ed., Down and Out in the Great Depression: Letters from the Forgotten Man, Foreword, Preface, Introduction, and Part I Course packet, 72-75 (Roosevelt, “First Inaugural Address”) PREP: Think about what McElvaine says about his purposes in editing this collection, and his sense of the meaning it has. What does it mean to read a collection of sources and find them “moving”? Also note the arguments he makes in his introduction. Then look at the primary sources in Part One, as well as the photographs located throughout the text. What kind of source is this? What advantages and disadvantages do we encounter working with a source such as this? Finally, do you know anything about your own family’s experiences in the Great Depression? If not, think about asking someone about them. All it takes, in many cases, is a phone call! DUE: You will take your SECOND QUIZ in class TODAY. (F) February 26 Exploring Life Through Letters READING: McElvaine, ed., Down and Out in the Great Depression, Selections, Parts II, II and IV PREP: Begin to think about the paper you will write using McElvaine’s book. You will see that you have a couple of options for the paper—writing a paper about a particular kind of experience during the Great Depression or writing a review of McElvaine’s collection. We will spend our time in class today talking about and thinking about these papers, due next week. As you select the particular chapters you will read for today, consider your own interests for the upcoming paper. Watch for themes and issues you see emerging, and begin to develop your own insights on the basis of this primary source reading. 14 Week #7 (M) February 29 Paper Workshop! READING: No new reading for today. PREP: Bring at least your introduction and one body paragraph to class today. We will spend time in class reviewing thesis statements and working in small groups doing some peer editing. 15 (W) March 2 READING: The United States at War: The Good War? Foner, Give Me Liberty, ch. 22 Course Packet, 76-77 o Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Declaration of War Speech” Foner, Voices of Freedom, 187-189, 194-196, 200-209 o Franklin D. Roosevelt on the Four Freedoms o Henry R. Luce, The American Century o World War Two and Mexican Americans o African Americans and the Four Freedoms o Justice Jackson, Dissent in Korematsu v. United States PREP: Compare Roosevelt’s Declaration of War speech to the Declaration of War speech offered by Wilson in anticipation of World War One. What similarities and differences do you find in the rhetorical choices each made? In their presentation of Americans? The nation’s enemies? Next think about how Roosevelt and others defined American purposes in the world. Finally, read the primary sources about American life during the war. How should we understand the contradictions evident here? (F) March 4 An Introduction to the Cold War DUE: Your SECOND PAPER is due in class TODAY!! Week #8 (M) March 7 The Emergence of a Bi-Polar World READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, pp. 707-722 Foner, Voices of Freedom, 213-228 o Truman Doctrine o NSC 68 o Walter Lippmann, A Critique of Containment o United Nations Declaration of Human Right Moodle: Novikov Telegram PREP: During World War Two the United States was allied with the Soviet Union. How do you explain the growing tension between the two nations? How did the United States imagine the Soviet Union? What similarities and differences do you see as you explore the Soviet understanding of the United States? 16 (W) March 9 Americans and Cold War Culture READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, 722-735 Foner, Voices of Freedom, 229-240 o President’s Commission on Civil Rights, To Secure These Rights o Joseph R. McCarthy, Speech to Congress o Henry Steele Commager, “Who is Loyal to America?”240 Gilbert King, Devil in the Grove, Prologue and chs. 1-4 Moodle: o View the short educational film “Duck and Cover” PREP: Given the rise of McCarthyism, should we think of the impact of the Cold War as similar to, or different from, that we have seen with other wars? How, in turn, does the film “Duck and Cover” narrate the new atomic era? What other messages, including implicit ones, does the film communicate. Finally, begin Devil in the Grove. What kind of text is this? How are you going to handle the level of detail it offers? What seem to be important themes/arguments in the text so far? DUE: You will take your THIRD QUIZ in class today. (F) March 11 Race and the Realities of Early Cold War Culture READING: Gilbert King, Devil in the Grove, Prologue and chs. 5-10 PREP: Compare the situation for African Americans in Florida in 1949 to what we learned about the postReconstruction period. What has changed? What has remained the same? How do you account for the willingness of Thurgood Marshall to take on the racial status quo? Over the break, continue reading Devil in the Grove. It’s a great read, and getting ahead will allow the return to campus to be a bit less onerous! Enjoy Spring Break!! See you back here in a week. Week #9 (M) March 21 Devil in the Grove READING: King, Devil in the Grove, chs. 11-16 PREP: How did gender intersect with race in Florida in 1949? Step back and think a bit about this text as a secondary source. What are its strengths? How is it useful to us in History 153, even though it is a tightly focused story in some ways. In turn, do you discern any weaknesses in this book as a work of history? If so, what are they, and how do they affect your reading of the text? 17 (W) March 23 Race and Politics in the 1950s: The National Scene READING: King, Devil in the Grove, chs. 17-22 and Epilogue Foner, Give Me Liberty, 754-764 Foner, Voices of Freedom, 263-267 o Martin Luther King Jr. and the Montgomery Bus Boycott Course Packet, 78-84 o Court Opinion, Brown v. Board of Education o Southern Manifesto PREP: How would you characterize American culture in the years from 1945-1960? Was the south exceptional in its racial dynamics in the 1950s, or did it simply exaggerate national tendencies? What does the story presented in Devil in the Grove suggest about the mechanisms and actions necessary to overturn white supremacy? How, in turn, do those who oppose the ruling in Brown make their case against it? (F) March 25 An Affluent Society: Repression and Rebellion in Cold War America READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, 736-754, 764-767 Foner, Voices of Freedom, 244-253, 256-262 o Richard M. Nixon, “What Freedom Means to Us” o Clark Kerr, Industrialism and Industrial Man o Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom o C. Wright Mills, on “Cheerful Robots” o Allen Ginsberg, “Howl” Course Packet, 85, 139-147 o “Help Wanted” o Ads and articles on Fallout Shelters Moodle: View the educational film “A Date With Your Family” or “The House in the Middle” PREP: How are the concerns of Americans in the 1950s similar to and different from those we observed at the turn of the century? How do you explain the differences? How would you explain this culture, which will soon give rise to the activism of the 1960s? (M) March 28 The Complex Politics of the 1960s READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, ch. 25 Course Packet, 86-87 o John F. Kennedy, “Inaugural Address,” 1961 Foner, Voices of Freedom, 272-281 o The Sharon Statement o Barry Goldwater, “Extremism in Defense of Liberty” o Lyndon B. Johnson, Commencement Address at Howard University Week #10 PREP: Think about the goals set by both Kennedy and Johnson for their presidential administrations, the New Frontier and the Great Society. What goals did they share? How were they different? What definition of “liberalism” did their administrations seem to adopt? How did their domestic visions relate to their foreign policy goals? How might we understand the attraction of liberalism in the early 1960s? Now consider the alternative vision, offered by the conservatives who wrote the Sharon Statement, and by Barry Goldwater. Why were conservative views less popular at this historical moment? 18 (W) March 30 The Torch Has Been Passed: A New Generation, A New Politics READING: Foner, Voices of Freedom, 268-271, 282-288, 290-300 o Martin Luther King, Letter from Birmingham Jail o Students for a Democratic Society, Port Huron Statement o National Organization for Women, Statement of Purpose o Cesar Chavez, “Letter from Delano” o The International, 1968 Course Packet, 88-100, 129-138 o Malcolm X, “The Ballot or the Bullet” o Anne Moody, Coming of Age in Mississippi PREP: The 1960s were defined, in part, by the emergence of youth culture and youth activism. Begin by reading King’s letter very closely. How does he explain the need for civil rights activism? Of whom is he especially critical? Now note the differences between the perspectives and rhetoric of King and Malcolm X. Are there also similarities and resonances? How does Anne Moody help us understand the realities of the civil rights struggle? Finally, read the other documents. How are these other emerging movements linked to the African American civil rights and black nationalist struggles? (F) April 1 Fighting the Cold War: An Introduction to the War in Vietnam READING: Foner, Voices of Freedom, 210-213 o Declaration of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam Course Packet: 101-114 o Gary R. Hess, “South Vietnam Under Siege, 1961-1965” o Gulf of Tonkin Resolution Philip Caputo, A Rumor of War, Prologue and chs. 1-6 PREP: Why did the United States go to war in Vietnam? How, in turn, was the war experienced by soldiers who served in the first years of the war, as Caputo did? Week #11 (M) April 4 Fighting the War READING: Foner, Voices of Freedom, 288-290 o Paul Potter on the Antiwar Movement Philip Caputo, A Rumor of War, chs. 6-10, 15-18 PREP: What does Caputo mean when he says, on page 323, “The explanatory or extenuating circumstance was the war”? Do you agree? 19 (W) April 6 Conservatism Resurgent? The Nixon Years READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, 806-816 Foner, Voices of Freedom, 301-303, 316-318 o Brochure on the ERA o Phyllis Schlafly, “The Fraud of the Equal Rights Amendment” Listen to selections of the Richard M. Nixon, White House Tapes, by visiting : http://millercenter.org/presidentialrecordings/nixon/watergatecollection Read and listen to “Smoking Gun” and at least three other selections. PREP: How would you compare President Nixon’s approach to the war in Vietnam to that exercised by Presidents Kennedy and Johnson? How, in turn, do you make sense of the Watergate scandal? What was the President guilty of doing? Finally, what do the competing voices on the ERA suggest about American culture in the early 1970s? DUE: Your THIRD MEMO Is due in class TODAY!! (F) April 8 Quiz #4 READING: No new reading today. PREP: Use the extra time to catch up and prepare for the quiz. DUE: You will take your FOURTH QUIZ in class TODAY. Week #12 (M) April 11 ATAVIST TUTORIAL PREP: Recognizing your third memo is due on Wednesday, do the preparatory work before today’s class. This will also prepare you well for today’s tutorial on digital essays. (W) April 13 The 1970s: The Age of Limits? READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, 816-829 Foner, Voices of Freedom, 303-311, 319-321 o Barry Commoner, The Closing Circle o Jimmy Carter on Human Rights o James Watt, “Environmentalists: A Threat to the Ecology of the West” Visit the PBS website about the Stonewall Rebellion and read the introduction and primary sources at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/introduction/stonewall-intro/ PREP: Historians sometimes describe the 1970s as an “age of limits.” How would the political situation, both national and international, fit with this interpretation? How did the new gay rights activism fit into this discussion? The new environmental movement? The movement for human rights? 20 (F) April 15 Conservatism Triumphant READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, 829-839 Foner, Voices of Freedom, 321-323, 311-315 o Ronald Reagan, “Inaugural Address” o Jerry Falwell, “Listen America!” PREP: How did Ronald Reagan conceptualize conservatism? How did he understand the role of the federal government? Of state government? What values undergirded his articulated viewpoints? Now, do these seem like a conservative “revolution”? Week #13 (M)April 18 Closing Years of the Twentieth Century: New Challenges? READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, ch. 27 Foner, Voices of Freedom, 324-340 o Pat Buchanan, “Speech to the Republican National Convention o Bill Clinton, “Speech on Signing NAFTA” o Declaration for Global Democracy o The Beijing Declaration on Women o Puwat Charukamnoetkanok, “Triple Identity: My Experience as an Immigrant in America” Course Packet, 115-121 o “Contract with America” You can also read a more comprehensive version at: http://web.archive.org/web/19990427174200/http://www.house.gov/house/Contract/CONTRACT. html PREP: Compare the presidency of Bill Clinton to those of earlier leaders. How would you characterize his political position? That of Pat Buchanan? The authors of the “Contract with America”? What sense do you gain of American culture at the end of the twentieth century from the combination of primary sources in today’s reading? (W) April 20 America and the World: September 11th READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, 874-878 Moodle: o History Channel documentary, 102 Minutes that Changed America https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIWKNNer1Cc o George Bush 9/11 speech http://edition.cnn.com/2001/US/09/11/bush.speech.text/ Visit the website for the 9/11 Memorial in New York City at: http://www.911memorial.org PREP: First, watch the film on 9/11. How does it narrate the tragedy? How, in turn, did George Bush explain the 9/11 attacks? Finally, look at the Ground Zero memorial website. What does it tell you about how Americans are thinking about themselves in the world? 21 (F) April 22 The Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan READING: Foner, Give Me Liberty, 878-909 Foner, Voices of Freedom, 341-351, 357-362 o The National Security Strategy of the United States o Robert Byrd on the War in Iraq o Second Inaugural Address of George W. Bush o Opinion of the Court, Lakhdar Boumediene et al v. George W. Bush o Barack Obama, “Speech on the Middle East” Course Packet, pp. 122-123 o George W. Bush, “Operation Iraqi Freedom” Moodle: View the film Restrepo on the war in Afghanistan PREP: How would you compare President George W. Bush’s speech on “Operation Iraqi Freedom” to other declaration of war speeches we have read this semester? How does he explain the need for this war? What is the Bush Doctrine, and again, how is this like or unlike other foreign policy stances taken by the United States? Finally, what are the competing views about American intervention in Afghanistan and Iraq? How did President Obama attempt to redefine the American relationship to the Middle East in 2011? Has he succeeded? Week #14 (M) April 25 Immigration Debates and the Lives of Undocumented People READING: Peter Orner, ed., Underground America: Narratives of Undocumented Lives, 1-17, 347-361, 385389 o Luis Alberto Urrea, Foreword o Introduction, “Permanent Anxiety” o Editor’s Note and Note for the 2013 Edition o Editor’s Note for the Afterword o Lorena, Afterword o Appendices A-C o Glossary o At least three narratives of your choice Foner, Voices of Freedom, 351-354 o Archbishop Roger Mahoney, “Called by God to Help” Visit the website of at least one Republican and one Democratic presidential candidate to read up on their position on issues around immigration. PREP: Issues around immigration have received significant attention in recent months, particularly in the arguments of candidates for the presidency. Today we will focus, first, on the experiences of those living as undocumented residents of the United States. Why have people come to the United States outside of the established channels for immigration? What risks and costs have these choices involved? What are their experiences of life inside the United States? How are these like or unlike what we know about immigrant experiences a century ago? What similarities and differences do you note among the narratives you have read? Finally, how are different candidates defining national identity as they talk about immigration issues? 22 (W) April 27 Between the World and Me: Black Life in the 21st Century READING: Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me, Part I (to page 71) Course Packet, 124-126 o Jennifer Schuessler, “Drug Policy as Race Policy” PREP: Why do you think Coates wrote this book to his son? Why now? Select one passage from Coates’ work that you would like to discuss in class today. Look for something that seems important, or challenging, or confusing, even troubling. (F) April 29 Final Quiz / Paper Workshop READING: No new reading for today. Catch up and review for your final quiz. PREP: Be ready to ask any questions you have about the Research Project, due on the last day of class. DUE: You will take your FINAL QUIZ in class TODAY!! Week #15 (M) May 2 Black Lives Matter? READING: Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me, complete PREP: As you think about what Coates is sharing about his experiences of living as an African American in the United States, place his narrative in its historical context. What is new, and what seems to resonate with earlier discussions about the racial dynamics of the United States? Peruse the internet to see how the Black Lives Matter movement is being portrayed by a range of American voices. How do different Americans define national identity in these debates? (W) May 4 FINAL PAPERS DUE PREP: Finish your research projects for class today. 23 Have a GREAT SUMMER!! 24 ABOUT CAMPUS EMERGENCIES Classroom Emergency Resonse Guide Please review university emergency preparedness and response procedures posted at www.pugetsound.edu/emergency/. There is a link on the university home page. Familiarize yourself with hall exit doors and the designated gathering area for your class and laboratory buildings. If building evacuation becomes necessary (e.g. earthquake), meet your instructor at the designated gathering area so she/he can account for your presence. Then wait for further instructions. Do not return to the building or classroom until advised by a university emergency response representative. If confronted by an act of violence, be prepared to make quick decisions to protect your safety. Flee the area by running away from the source of danger if you can safely do so. If this is not possible, shelter in place by securing classroom or lab doors and windows, closing blinds, and turning off room lights. Stay low, away from doors and windows, and as close to the interior hallway walls as possible. Wait for further instructions.