3. Early China, Nubia & the Americas

advertisement

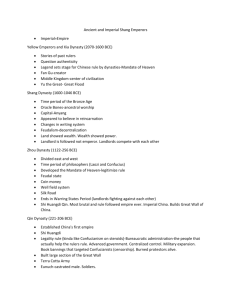

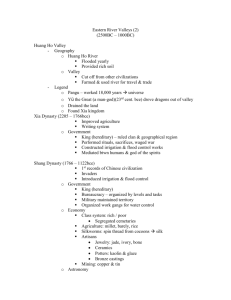

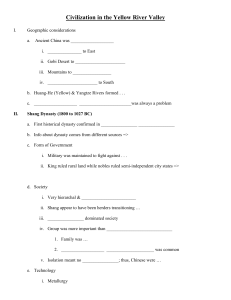

New Civilizations in the Eastern & Western Hemispheres, 2200-250 BCE Tracy Rosselle, M.A.T. Newsome High School, Lithia, FL Early China, 2000-221 BCE Nubia, 3100 BCE to 350 CE The Americas: Olmec & Chavin, 1200-250 BCE The loess life is more Civilization emerged in China somewhat later than in the Middle East and India, and centered around the northern Huang He River (Yellow River, so named because of its yellowish-brown dust called loess that’s suspended in its waters). Yellow River known as “China’s Sorrow” because it altered course many times, bringing tremendous destruction. Geography and early China China is isolated from the rest of Eastern Hemisphere: natural boundaries include Himalayas to the southwest, Pamir and Tian mountains and Takla Makan Desert to the west, Gobi Desert and Mongolian steppe to the northwest … and the Pacific Ocean to the east. Neolithic cultural complexes have been identified but not understood, and stories of ancient dynasties including the Xia are hard to assess, so Chinese history proper begins with the Shang dynasty around 1750 BCE. Shang rulers dominated central and northern China for more than six centuries and were the first to leave written records. A warrior aristocracy The Shang fought its northern and western neighbors (considered barbarians) with the help of its bronze weapons and horse-drawn chariots. A longstanding Chinese tradition of ethnocentrism arose: The Shang viewed themselves as superior, as being at the center of the universe – and China was seen as the “Middle Kingdom.” Trade from the outset The Shang traded fairly extensively – perhaps even with peoples as far away as Mesopotamia – and early on became experts in the production of pottery and silk. Shang pottery has been found in India. Chinese system of writing with pictograms started with the Shang and fundamentally endures to this day. (The Chinese written language can be read everywhere in China, regardless of regionally spoken variants such as Mandarin and Cantonese. It now contains more than 50,000 characters.) Oracle bones Earliest evidence of Chinese writing Animal bones and tortoise shells on which priests would scratch questions for the gods Answers interpreted depending on how the bones cracked when touched with a hot poker Shang kingship – tied to the heavens The Shang ideology of kingship glorified the king as the indispensable intermediary between the people and the gods. Royal family and aristocracy worshipped the spirits of their male ancestors, believing they had an “in” with the gods – to whom they practiced animal and even human sacrifice! Using oracle bones was part of divination, determining the future through the will of the gods. Shang sets the tone The family has been one of civilization’s most important institutions, and nowhere was that more true than in Shang China. This first dynasty set the tone for China’s patriarchal society, in which the husband and father dominated and multiple generations of the same family lived under the same roof. Began practice called well field system: peasants worked on lands owned by their lord but also had land of their own they cultivated for their own use. Shang bronze The Shang are perhaps best known for their mastery of the art of bronze casting. Utensils, weapons and ritual objects made of bronze have been found in royal tombs in urban centers throughout their sphere of influence. Shang dynasty bronze pot with lid and handle The Zhou dynasty The Zhou (joe) line of kings (c. 1027-221 BCE) was the longest lasting and most revered in China’s dynastic history. The last Shang king was defeated by Wu, the ruler of Zhou, which was a dependent state in the Wei (way) River Valley. It might be said of the Zhou that they were some of the first to use propaganda to legitimize their rule new theory: “Mandate of Heaven.” “Mandate of Heaven” The ruler (“Son of Heaven”) had been chosen by the supreme deity (“Heaven”) and would remain in his good graces so long as the ruler was a wise and just guardian of his people. Proof of this divine favor was in the pudding: prosperity and stability continuation of the dynasty … but corruption, violence, arrogance, natural calamities, insurrection meant divine displeasure (the mandate was lost) and a new dynasty. Strictly speaking, this is a tautological (or circular) argument, one that begins by assuming its own proof … but it became central to the Chinese view of government. Bureaucratic decentralization The Zhou kings continued many of the Shang traditions but separated religion (and divination) from government. Like the Shang, their rule was decentralized: nobles were given protection and power over smaller regions in return for loyalty to the king very much like feudalism, which would later emerge in Japan and Europe. More than a hundred of these largely autonomous territories, where bureaucracies grew to administer government efficiently. (Ruling through bureaucracy would prove to be a Chinese tradition for thousands of years.) Zhou innovations in trade and technology Roads and canals were built to stimulate trade and agriculture. Coined money further improved trade (though most people continued to barter and taxes were often paid with grain). Blast furnaces produced cast iron that wouldn’t be matched in Europe until the Middle Ages. Zhou-era bronze coins Zhou trade While the well field system carried on (and later was characterized as the ideal by Confucian scholars), trade and manufacturing was done by merchants and artisans living in walled towns under the direct control of the local lord. Merchants were not independent; instead, considered property of the lord and sometimes were even bought and sold. Although slavery was probably not extensive, a class of slaves performed menial tasks and perhaps worked on irrigation projects. Nomads to the north and west The Zhou had seized power in part because of military prowess honed against pastoral nomads to the west. For millennia the Chinese had a unique relationship with these nomadic peoples from the arid, grassy steppes of central Asia: quarreling but also trading (e.g., goods for horses) as the nomads served as intermediaries in the central Asian trade network. Zhou in decline Power already started to wane as early as 800 BCE as the Zhou a) fought increasingly with nomads to the northwest, and b) had to deal with local rulers hording power, becoming more independent within their own kingdoms and fighting neighboring rulers. The following 500 years: Eastern Zhou era capital moved to more secure location in the east. Fragmentation leads to war Fierce competition and eventually warfare among small, independent kingdoms within China (Zhou rulers couldn’t keep a lid on it all) “Warring States Period” 480-221 BCE * When China finally unifies in 221 BCE under Qin Shi Huangdi, the First Emperor, he orders the destruction of all books that don’t carry utilitarian value. He feared poetry, history, philosophy might undermine his government … so much of China’s early literary tradition – which reflects society’s social and cultural legacy – is lost. China’s Axial Age Axial Age – term coined by German philosopher Karl Jaspers, referring to a 600-year period during the first millennium BCE when profoundly influential ideas about religion and philosophy sprang forth: monotheism, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, Greek philosophical rationalism. In China, amid the troubled times of the declining Zhou dynasty, three social or ethical belief systems arose: Legalism, Confucianism, Daoism. Legalism Authoritarian political philosophy Human nature is essentially wicked. People keep in line only if compelled by prospect of severe punishment, instituted by a strong central government run by an absolute ruler. Practical matters sustained society: farmers and fighters the ideal professions. Basis of the unified Qin dynasty (which we’ll discuss later on), but resentment of its harshness led to wider acceptance of Confucianism and Daoism. Confucianism Confucius considered himself a failure, but his disciple Mencius spread his ideas and influence later on. Confucius (551-479 BCE) was a scholar who wanted to restore the order and moral living of earlier times. Disciples collected his words in the Analects. His doctrine of duty and public service became central to Chinese society and politics, and it also influenced Korea and Japan. Confucianism Relationships rule Most important concepts: Ren – appropriate feelings (sense of humanity, kindness, benevolence) Li – correct actions (sense of propriety, courtesy, respect, deference to elders) Xiao – filial piety, or respect for family obligation Confucius believed that administrators could rule through enlightened leadership, modeling these traits for the larger society. Confucianism Five key relationships Order is achieved when people know their proper role and relationship to others: 1. Ruler to subject 2. Father to son 3. Husband to wife 4. Older brother to younger brother 5. Friend to friend Confucianism Family and state Confucius drew a parallel between the family and the state: family hierarchy – father at the top, sons next, then wives and daughters in order of age state hierarchy – ruler at the top, public officials as the sons, common people as the women Confucianism Not a religion Confucianism is an ethical belief system – a political and social philosophy – not a religion. It arose within the unique culture of China, so its influence remained there (and in surrounding regions in East Asia). Its flexibility was key (i.e., Buddhists could accept Confucianism, too). Daoism Laozi (low-dzuh) may have founded this philosophy in the sixth century BCE. Literal translation of the Dao: the way, the way of nature, or the way of the cosmos. Humans should exist in harmony. Daoism Relax … don’t worry Daoism advised people to relax and get in harmony with the Dao. Don’t worry about the troubled times … you can’t do anything about it anyway. Wuwei – concept meaning act by not acting: – – do nothing and problems will solve themselves, like nature. be like water, soft and yielding yet naturally powerful. Daoism The less government the better Daoists believed institutions were unnatural and dangerous. The ideal state: a small, self-sufficient town. Daoism added to the complexity of Chinese culture and provided an alternative to the proper (and hierarchical) behavior of Confucianism, but these two philosophies were not mutually exclusive in practice: people could be Confucian at work and Daoist at home. Nubia Nubia is the name for the thousand-mile stretch of the Nile Valley covering land in modernday Egypt and Sudan. Nubia enters the historical record around 2300 BCE. Linking north and south Nubia is the only continuously inhabited stretch of territory connecting sub-Saharan Africa (the lands south of the vast Sahara Desert) with North Africa. For thousands of years it has served as a corridor for trade between tropical Africa and the Mediterranean. Its land is a treasure-trove of natural wealth, with rich deposits of gold, copper and semiprecious stones. Trade with Egypt Egyptian craftsmen more than 4,000 years ago were already working with ivory and ebony wood – products of tropical Africa that must have come through Nubia. Noblemen stationed along the southernmost region of ancient Egypt led donkey caravans south in search of gold, incense, ebony, ivory, slaves, exotic animals dangerous missions, which must have entailed delicate negotiations with Nubian chiefs. New ideas on Nubia Nubia was traditionally seen as a derivative culture lying on the outskirts of Egypt, but scholars now emphasize its interactions with Egypt. There’s growing evidence that Nubian culture synthesized influences not just from Egypt but also from sub-Saharan peoples. Egyptians penetrate south During the New Kingdom era (1532-1070 BCE) the Egyptians expanded deeply into Nubia, crushing a kingdom they called Kush, the capital of which was located at Kerna, just below the Nile’s 3rd cataract and one of the earliest urbanized centers in tropical Africa. Nubians absorbed Egyptian culture, as children of Nubian elite were brought to the Egyptian royal court (to ensure good behavior of their relatives down south) and then returned home later on. Domination and decline Egypt dominated Nubia for 500 years before its own weakness eroded its authority there. Kings of Nubia ruled Egypt (c. 712-660 BCE) as the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. Nubian civilization’s epicenter shifted south to Meroe (below the 5th cataract) after the fourth century BCE. Sub-Saharan cultural patterns gradually replaced Egyptian ones. Meroe was a huge city for its time, and much of it is still buried under sand. The Americas: Olmec up first This map shows the location of the Olmec civilization, in relation to the much later Mayans and Aztecs. Olmec (c. 1200-400 BCE) Mesoamerica is the name for a region that stretches from central Mexico to northern Honduras, and a complex civilization arose there around 1200 BCE, independent of outside influences. Olmec – the “mother civilization” of Central America Like, but unlike, Eurasia Agricultural surpluses included corn, beans and squash – foods unknown in the “Old World” – and historians now believe an extensive trading network thrived from what is now Mexico City to Honduras. The Olmec homeland featured numerous streams and small rivers (which periodically flooded and provided fertile soil for farming), but the region’s lush jungle environment and heavy rainfall is a stark contrast to the major river valleys where civilizations first emerged in Eurasia and Africa. The same basic patterns of civilization transpired in Mesoamerica, though. Authoritarian Olmecs The Olmecs were polytheistic, carved out Colossal Heads (up to 9 feet tall and weighing 20 tons each – no small feat considering they had no large draft animals) presumably in homage to their authoritarian leaders, and apparently had a social structure indicated by clothing and ornaments (i.e., the more elaborate the dress and decoration, the higher the social class). Influential Olmecs The Olmecs influenced later Mesoamerican civilizations, such as the Maya (we’ll discuss them in the next period – 600 to 1450 CE). They worshipped a variety of nature gods; Olmec sculptures prominently depict a half-human, halfjaguar spirit, which may have been a powerful rain god. They also developed a writing system and calendar, but in the absence of metal technology, fashioned knives and such from obsidian. Mysterious end The civilization died out around 400 BCE for mysterious reasons. Historians speculate these people fell to invaders … or possibly just destroyed their own monuments upon the death of their rulers. Like the humid climate of China, this region’s early history hasn’t stood up well to time. Houses and temples were built of wood and thatch (which decompose over time), so Olmec sites today consist mainly of earthen mounds and stone monuments. Meanwhile in South America … In South America, urban centers developed around the same time but in isolation from those in Mesoamerica. Eventually, however, the two regions interacted: the later introduction of metallurgy in Mesoamerica and, likewise, the later appearance of maize (corn) agriculture in the Andes, suggest sustained trade and cultural contact. Important crops here were beans, peanuts and sweet potatoes. Chavin (c. 900-250 BCE) The first civilization arose in the harsh, dry and mountainous Andes in Peru. The Chavin (cha-VEEN or –BEAN) apparently developed no discernable political or economic institutions, so archaeologists named the culture after a major ruin of pyramids, plazas and massive earthen mounds. Polytheism continues to proliferate The Chavin are thought to have been essentially a polytheistic religious cult. They made small tools out of copper and are thought to have developed bronze technology. They were unique in that they domesticated llamas as their “beasts of burden.” Artisans worked with ceramics, textiles and gold. Both Olmec and Chavin arose outside the context of a major river valley, but both would leave a legacy to be built upon by later civilizations. Sources The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History (Bulliet et al.) Traditions & Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past (Bentley & Ziegler) World History (Duiker & Spielvogel) Patterns of Interaction (McDougal Littell, publisher) AP World History review guides: The Princeton Review, Kaplan and Barron’s