Unit 7 Slides

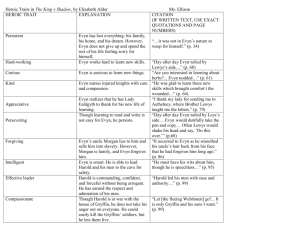

advertisement

UNIT SEVEN: THE AGE OF CHARLEMAGNE Islamic Art and Architecture Calligraphy Illuminated Qur'an made for Ilkhanid ruler Uljaytu Hamadan, 1313 "Mohammed is the messenger of Allah" (From the Holy Qur'an: Surah: 48, Al-Fat'h, verse: 29) Those who teach me have my everlasting respect (A common saying) There is no God who truly deserves to be worshipped but Allah alone and Mohammed (peace and blessings be upon him) is the messenger of Allah He Who taught (the writing) by the Pen (From the Holy Qur'an, Surah: 96, Al- 'Alaq, Verse: 4) Praise be to Allah; the Cherisher and Sustainer of the Worlds (From the Holy Qur'an, Surah 1, Al-Fatiha (The Opening)) Shrines and Palaces Ka'ba Mosque of the Prophet Mohammed (peace be upon him) in Madina Panoramic view of the Dome of the Rock An inner view of the dome of the Dome of the Rock Tunisia's Great Mosque of Qairawwan The Great Mosque of al-Mutawakkil which is also know as The Spiral (al-Malwieyya) Located in Samarra, Iraq, the Great Mosque of al-Mutawakkil (reign 847 - 861) is also know as The Spiral (al-Malweyya). Shown here is the mosque's 165-foot high minaret that is located about 90 feet from the mosque's north side. The base of the minaret originally was connected to the mosque with a viaduct. The Taj Mahal (Crown of the Palace) The Great Mosque of Cordoba Alhambra Palace in Granada The Alhambra courtyard facade overview and reflection The Alhambra through archway across garden and fountain The Alhambra close-up of ornamental mosaic Symmetric Patterns at the Alhambra This wallpaper pattern has rotational symmetry (by what angles?) Can you find the centers of rotation? Try drawing the pattern on square graph paper. The name 'Oriental carpets' is usually referred to all hand-knotted carpets; since this denomination is not inexact in view of their common Asiatic origin. However, the immensity of the producing areas, and the variety of techniques, styles, and materials used necessitate a detailed classification. As a rule, Oriental carpets are divided into four main groups: Caucasian; Central Asia or Turkestan; Persian; and Turkish or Anatolian. Caucasian rugs Baku Talish Persian Central (Kashan) Southwestern (Bakhtiari) Turkish Central Anatolia (Konya) Western Anatolia (Bergama) Early Medieval, Celtic Timeline view of Celtic Art and Culture Castledermot, South Cross Type of object: Sculpture Material: stone Period: Early Medieval, Celtic Find spot: Co. Kildare Country: Ireland Date: 9th c. CE North Cross West face Type of object: Sculpture Material: stone Period: Early Medieval, Celtic Find spot: Ahenny, Co. Clare Country: Ireland Date: 9th c. CE St. Columba's House Type of object: Architecture Period: Early Medieval, Celtic Find spot: Iona Country: Scotland Date: c. 800 Muiredach's Cross West face Type of object: Sculpture Material: stone, quartzy sandstone Period: Early Medieval, Celtic Find spot: Monasterboice, Co. Leath Country: Ireland Date: c. 900-920 CE Tall Cross Detail, Flight into Egypt Type of object: Sculpture Material: stone, granite Period: Early Medieval, Celtic Find spot: Moone, Co. Kildare Country: Ireland Date: 9th c. CE Brooch-pin Leng., 6.25 cm. Type of object: Jewelry Material: silver-gilt Period: Early Medieval, Celtic Find spot: Westness Country: Scotland Date: 8th c. CE Collection: Edinburgh, National Museum of Scotland Large Pottery Beaker Type of object: Vessels (ceramic) Material: clay Period: La Tène Find spot: La Cheppe Country: France Date: 5th c. BC Collection: Paris, St-Germain-en-Laye, Musée des Antiquités Mould for Applique Figure of Wheel-God (Ht.,5 3/4) fr. Corbridge, Northumberland Type of object: Vessels (ceramic) Material: clay Period: Romano-Celtic Find spot: Corbridge, Northumberland Country: England Date: 3rd c. CE Collection: Corbridge Museum Ceremonial Axe and Spear Type of object: Armor and Weapons Material: bronze Period: Hallstatt Find spot: Krottenthal Country: Germany Date: 9th c. BCE Collection: Munich, Prähistorische Staatssammlung, Museum für Vör-und Frühgeschichte Helmet Type of object: Armor and Weapons Material: bronze Period: La Tène Find spot: Marne Country: France Date: 400-200 BCE Collection: Paris, St-Germain-enLaye, Musée des Antiquités Sword Scabbard Detail Type of object: Armor and Weapons Material: bronze Period: Insular La Tène Find spot: Lisanacrogher, Co. Antrim Country: Ireland Date: 2nd c. BCE Collection: Dublin, National Museum of Ireland Sword Type of object: Armor and Weapons Material: bronze Period: Hallstatt Find spot: Schippach Country: Germany Date: 6th c. BCE Collection: Munich, Prähistorische Staatssammlung, Museum für Vörund Frühgeschichte GERMANIC (TEUTONIC) EUROPE The Burgundian Kingdom (5-7th c. A.D.) Ivory buckle from the tomb of St. Caesarius of Arles, Notre Dame la Major. 6th c. Perhaps showing two soldiers attending Christ's tomb. Reflects 6th-century fusion of Roman and Germanic culture. The Burgundian Kingdom (5-7th c. A.D.) Tin-plated bronze buckle showing Daniel in the lions' den. Burgundian 7th c. The Alemanni (4th to 8th c. A.D.) Ceramics from the grave of an Alemannic aristocratic youth, 4th c., which are close to Roman models. Because Alemann ethnogenesis occurred within the Roman cultural sphere, the Alemanni were highly Romanized. The Alemanni (4th to 8th c. A.D.) Helmet from a Alemann aristocratic grave, beg. 6th c. In the 4th and 5th c., the Alemanni were often at war with the Franks, and at the time of Clovis (c. 506) were beaten. While some chiefs fled to Theodoric, most Alemmann dukes were thereafter left to govern Alamania under the authority of the Frankish kings. The Alemanni (4th to 8th c. A.D.) Alamann pressed lead repoussé sword hilt. 7th c. From Guttenstein, Baden. PreChristian theme, perhaps a human figure wearing an animal mask at a sacred tree. The Alemanni (4th to 8th c. A.D.) "Casket of Teudericus" reliquary from the second half of the 7th c. (?) (Canton Valais: Saint Maurice Abbey treasury). This reliquary is a product of the monastic workshop of St. Maurice d'Agaune. Signed by the artist and dedicated by the Priest Teudericus to the monastery. Gold cloisonné, gemstones, and cameo on wood. 5.25" The Franks (4th to 7th century A.D.) Frankish sword hilt from the grave of Childeric at the royal villa at Tournai, late 5th century A.D. (Paris: Bib. Nat. Cab. des Méd.). The Merovingian dynasty had a legitimate function within imperial government as the army and administration of much of Gaul. While the Franks to interacted with the GalloRoman population rather more than some other sub-Roman regional monarchies, social and cultural synthesis occurred only slowly. Therefore Merovingian art tends, like this example, to manifest both Roman and Frankish traditions. The Franks (4th to 7th century A.D.) Tankard. Bronze repoussé on wood. Lavoye gravegood. 7" tall. Frankish, ca. 500 A.D. (S. Germain en Laye, Mus. d'Art). Christian-Classical motifs with Frankish stylization. The Franks (4th to 7th century A.D.) Helmet from Frankish aristocratic grave at Krefeld, Gellep, ca. 525 A.D. Helmet style is Sassanian type introduced by the Romans, with Persian, Germanic and Christian motifs. Possibly a Mediterranean import or possibly of Frankish manufacture. The Franks (4th to 7th century A.D.) Casket of Mumma. Gilt copper repoussé on wood reliquary. Mid 7th c. A.D. (St. Benoit sur Loire: Abbey Church). 5 in. Shows Twelve Apostles (?) and decorative ornament. The Franks (4th to 7th century A.D.) A 7th c. Frankish grave stele from Niederdollendorf am Rhine (nr. Bad Godesberg). Late 7th c. A.D. The model is the traditional Frankish wooden grave pillar. 17 in. The long-haired owner is in the field with his flask and sword. A snake represents his soul. On verso is the earliest Germanic image of Christ. He is here represented as a king standing above an abstract decorative pattern consisting of the traditional interlace and broken stick. The Lombard Renaissance (6th century to 774 A.D.) Lombard fibula from Cividale di Friuli, second half 6th c. A.D. The Lombard Renaissance (6th century to 774 A.D.) Altar of Ratchis. Relief detail. Visitation of Mary. Ca. 740 A.D. (Cividale: St. Martin church museum). The Goths Pre-incorporation (4th - 5th c. A.D.) Ostrogothic fibula. Gold plates attached to a silver core and inlaid with garnets. 4th c. A.D. (New York: Metropolitan Museum). 6.25" The Gothic interest in fibula is adopted from Late Roman imperial emblems of rank at the imperial court. The Goths (4th to 7th century A.D.) Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy Ostrogothic looped eagle head fibula from a female grave at Desana, Italy. Ca. 500 A.D. (Turin: Mus. Vic.). Gold with enamel, garnet and emerald inlays. By wearing rich fibula, the top Ostrogothic aristocracy could gave tangible expression to its imperial service as the Roman court aristocracy had previously done. The Goths (4th to 7th century A.D.) Visigothic Kingdom of Toulouse and Toledo Map of the Kingdoms of Toulouse and Toledo The Goths (4th to 7th century A.D.) Visigothic Kingdom of Toulouse and Toledo Visigothic polychrome votive crown of Recceswinth, King of Toledo. Found in a votive crown hoard of c. 670 at Fuente de Guarrazar, near Toledo (Madrid: Mus. Argu). 7.8" Typical of Visigothic taste. The Anglo-Saxons (4th to 9th c. A.D.) Anglo-Saxon round fibula from the Kingtson Find. 7th c. A.D. (Liverpool Mus.) 3.25 in. Gold cloisonné with garnet and gemstone inlays. The round fibula is a late Roman motif. The Vendel Renaissance (Scandinavia, 4th to 8th c. A.D.) Vendel sword hilt from Grave V, Snartemo Hägebostad, Vest Agder, Norway. Hilt is repoussé Early 6th c. A.D. The Vendel Renaissance (Scandinavia, 4th to 8th c. A.D.) Vendel runestone with interlace and cross within a runic border, 5-6th c. A.D Germanic Cosmography Yggdrasil is the world tree in Germanic mythology. There is no explanation or tale explaining its creation. The Nordic cosmographical world is divided into three trisentric levels with a space separating each plate. The roots of this sacred Ash tie together the three levels of the world, and its branches the very heavens. In the first level of the world there is Asgard, Vanaheim, and Alfheim . The second level contains Midgard, Jotunheim, Nidavellir, and Svartalfheim. The third houses Hel and Nifelheim. The world tree is rooted in the realm of the Aesir, the realm of the frost giants, and the realm of the dead. The tree is subject to constant death and renewal. A dragon named Nidhogg gnaws at the roots and a squirrel called Ratatosk on the branches. Deer graze off the tree and leap on it. An eagle sits on top of the world tree stirring up the winds of the world with its wings. The squirrel runs up and down the tree delivering vindictive messages between the eagle and Nidhogg. The tree stays green and rejuvenated with the aid of the Norns . They sprinkle the tree with clay and water from the Spring of Urd to prevent Yggdrasil from rotting away. The spring of Urd, lies in Asgard and has very strong properties. Everything that touches these waters turns white. This well is also known as the well of destiny. The gods hold council by it. Carolingian Era: Iro-Frankish and Anglo-Frankish art Victor Codex. Tatian ms: 547. (Fulda: Lib. Codex Bonifacius 1). Irish hand, 8th c. A.D. The Codex was originally owned by Boniface. Miniature and incipit from Cadmug Evangelary, 800-833 A.D. Iro-Fulda school. (Fulda Lib. Codex Bonif. 3). Incipit of the Gospel according to Saint Mark from the Halberstadt Gospel. Anglo-Frankish school, 9th c. A.D. Metalwork Front binding from the Four Gospels, St. Gall. 9th c. A.D.. Back cover of the Four Gospels, from Saint Gall. 9th c. A.D. Except the four evangelists in the corners, reflects the Irish aesthetic. Carolingian Synthesis Miniatures Miniature from the Gospel of Ebbo: Saint Mathew. Before 823 A.D. (Epernay: Bib. Munic.) 17x14 cm. Miniature from the Four Gospels, showing Saint Mark. Reims school, 845-882. (New York: Morgan Library). Miniature from Hrabanus' De Laud showing Louis the Pious as defender of the Cross. (Wien: Aust. Nat. Lib. Cod. 652). Fulda School, circa 840 A.D. Carolingian frescos (8-10th c.) Fresco in north niche of the Crypt of Rabanus, Petersburg. Christ and some others. Fresco probably done by the monk Candidus in 822-842 A.D. Another fresco in Crypt of Rabanus, Petersburg, probably by Candidus. Carolingian metalwork (8-10th c.) Reliquary. Repoussé gilt bronze on wood. Frankish, 8th c. A.D. (Paris: Cluny) 3.75". Mary holding Christ child flanked by Peter and Paul. So-called sword of Charlemagne. 9th c. A.D. Bronze doors. The Wolfstür, Aachen Cathedral. These are the first medieval doors in bronze. Gold coin with head of Charlemagne. Carolingian architecture (8-9th c. A.D.) Aachen cathedral and Charlemagne's octagonal church, viewed from the Rathaus. Interior, PALATINE CHAPEL Aachen Germany 792-805 Book of Kells Book of Kells The Four Apostles The Lindisfarne Gospels The Lindisfarne Gospels is one of the most important inheritances from early Northumbria. Written and illuminated about 698 in honour of St Cuthbert, the famous Bishop of Lindisfarne, who died in 687, it is a masterpiece of book production and a historic and artistic document of the first rank. Monasticicism Monastery of Great Lavra THE ABBEY OF MONTECASSINO THE ABBEY OF MONTECASSINO THE ABBEY OF MONTECASSINO Anti-portico of the upper Cloister Bayeux Tapestry Edward the Confessor in 1064, informing Earl Harold that he must leave for Normandy to pay homage to Duke William and to confirm the agreement made between Edward and William in 1051 that William shall be king of England on Edward's death. Although a humiliating exercise for Harold, he would use the opportunity to try and arrange the release of Wulfnot and Harkon. Conforming to Edward's wishes, Harold departs to the coast with entourage where he will board a boat that will ferry him to William in Normandy. Unfortunately, the voyage was not straight forward. He was blown ashore prematurely in a storm and is captured by Guy of Ponthieu. Note the popularity of moustaches around this time. Guy of Ponthieu being in possession of Harold, sent word to William that he had captured the Earl. There is dispute today concerning the payment of a ransom. It is said that one was paid by William for this eminent visitor. Other accounts differ in that he refused. By using disguised threats, managed to persuade Guy of the error of his ways. This plate shows the handing over of Earl Harold to William. On the left we assume is Guy pointing to Harold whilst addressing William on the right. William and Harold discussing matters of relevance. Many meetings like this must have occurred. These men were a match for each other mentally and the exchanges must have been quite interesting to listen to. William would have tried to persuade Harold of his rightful claim to the English throne whilst Harold using all his political astuteness and guile would attempt to avoid this ultimate admission. William knew he had Wulfnot and Harkon as hostages and was in a strong position to force an oath of homage from Harold. The Godwins had always been anti Norman and must have realised that any submission or declaration of homage would ultimately harm Harold's chances of becoming the King of England on the death of Edward. Harold knew that he was a hostage in all but name, so he had to tread carefully at these meetings. Harold and William, it is said, became quite good friends and actually fought together. If Harold was ever to return to England, he would eventually have to make some oath of allegiance to William. Harold realised that he had no choice but to pay homage to William if he was ever to be allowed home and secure the release of Wulfnot and Harkon. This plate depicts the act of homage over holy relics. This must have affected Harold. This was the last thing he had ever wanted to do. What gave him comfort and which was confirmed to him on his return was that it was made under duress and hence, not valid. Only Harkon, his nephew, was allowed to return home with him. His brother Wulfnot remained a hostage for obvious reasons. The death of Edward the Confessor on the 6th January 1066." One of the characters in this plate must be Harold because Edward's last words were "I commend my wife to your care and with her my whole kingdom ". If these words were ever said by Edward are open to question. If they were, they could have been interpreted in a number of ways. Harold had no doubt.