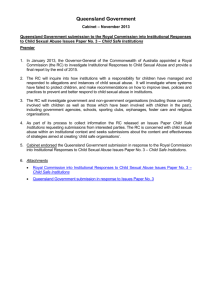

towards a safer and more consistent approach to allegations of child

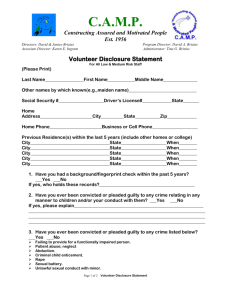

advertisement