Hume's Epistemology

advertisement

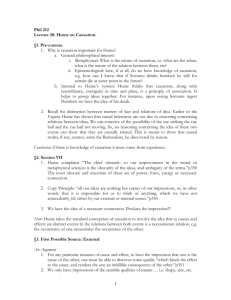

David Hume’s Epistemology • Scottish Philosopher • 1711 – 1776 • Strict Empiricist – Human knowledge extends only as far as actual human sense experience does. • Agrees, therefore, with Berkeley about sensible objects. – All that humans actually experience when they perceive sensible objects are bundles of sensible qualities. – Therefore, humans can take sensible objects to be only that, bundles of sensible qualities. – Humans have no rational basis for saying there are material objects in which sensible qualities inhere. • Critique of Mind – Hume applies the same reasoning he applied to sensible objects to the concept of mind (consciousness) or self. – All that humans actually experience is a passing parade of experiences. – Humans never actually experience a mind or self that has the experiences and binds them together into a unified consciousness. – Thus, there is no basis for calling the mind or self anything more than a bundle of experiences. – “For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe anything but the perception.” A Treatise of Human Nature (1739) – “The mind is a kind of theatre, where several perceptions make their appearance; pass, re-pass, glide away, and mingle in an infinite variety of postures and situations. There is properly no simplicity in it at one time, nor identity in different; whatever natural propension we may have to imagine that simplicity and identity.” A Treatise of Human Nature – Had he lived at a later time, Hume might have compared the mind to a never ending movie in which disconnected scene after disconnected scene passes one after another. – Humans only experience the never ending movie. – Humans never experience a mind or consciousness that unites the separate scenes to one another. • Critique of the Principle of Universal Causation – Everyone assumes, if only unconsciously, the Principle of Universal Causation. – Principle of Universal Causation: All events have a cause. – Hume claims humans have no rational basis for believing in the Principle of Universal Causation. – Two types of Truths • Relations of Ideas: Truths that are true because of the meanings of and the logical relationships between the ideas involved. – All bachelors are unmarried. • Matters of Fact: Truths that are true because they correspond to a direct sense experience. – The walls of Blinn classroom G241 are white. – The claim ‘All events have a cause’ is not a Relation of Ideas. • In the case of ‘All bachelors are unmarried’ unmarriedness is built into the definition of ‘bachelor,’ i. e. a bachelor is an unmarried man. • The definition of ‘event’ is ‘something that happens.’ • The definition of ‘cause’ is ‘to bring about.’ • Since ‘being brought about’ is not built into the definition of ‘event,’ the Principle of Universal Causation is not a Relation of Ideas. – The Principle of Universal Causation is not a Matter of Fact. • One never actually experiences one event’s causing another. • One experiences an event always immediately followed by another, i. e. a constant conjunction of events. • One, however, never actually experiences the first event’s bringing about the second. • One merely assumes that the first event brought about the second. • There is, however, no logically necessary connection between the first event’s happening and the second’s happening because one can imagine the first event’s happening without the second’s happening. • For example: – One can imagine placing a lighted match to a candle’s dry wick and the candle’s not lighting. – One can imagine that the candle, instead of lighting, shrieks in pain, sprouts legs, and runs away. – The point is that, unlike the connection between bachelorhood and unmarriedness, there is no logically necessary connection between placing a lighted match to a candle’s dry wick and the candle’s lighting. • Since humans never actually experience one event’s causing another, the Principle of Universal Causation is not a Matter of Fact. – Since it is neither a Relation of Ideas nor a Matter of Fact, the Principle of Universal Causation is not a genuine truth. – The Principle of Universal Causation, like the concepts of material objects and of the mind, is, philosophically speaking, a bogus concept. • Since humans can know only boring Relations of Ideas and very limited Matters of Fact, human knowledge is very limited. • Humans must take a skeptical attitude toward all other sorts of truth claims, e. g. the Principle of Universal Causation. • “When we run over libraries, persuaded of these principles, what havoc must we make? If we take in our hand any volume, of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, • “‘Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number?’ No. ‘Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matters of fact and existence?’ No. Commit it, then, to the flames. For, it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.” An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748) • Does all this mean that humans should no longer believe in, material objects, the mind (as a unified consciousness) or in the Principle of Universal Causation? – NO! • What it means is that humans should realize they believe in these things, NOT because they have a rational basis for their beliefs, but because they have an emotional need to believe in these things. • Following in the footsteps of the 17th Century English philosopher, Thomas Hobbes, Hume maintains humans find fulfillment, not by seeking and attaining truth, but by seeking and attaining pleasure. • As Hume himself says in the famous conclusion of his Treatise of Human Nature: “Most fortunately it happens that since reason is incapable of dispelling these clouds, nature herself suffices to that purpose, and cures me • “of this philosophical melancholy and delirium, either by relaxing this bent of mind, or by some avocation and lively impression of my senses, which obliterate all these chimeras. I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends; and, when after three or four hours’ amusement, I wou’d return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strain’d, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any farther.” • All this might be fine and well, perhaps, if everyone else were just like Hume, getting their pleasure from dining and conversing with friends and playing backgammon, but what if someone gets his pleasure from crashing jumbo jet liners into skyscrapers? • In that case, would you still feel as sanguine about Hume’s contention that humans are fundamentally emotional, not rational, beings? • Our next epistemologist, Immanuel Kant, could not accept that humans were essentially emotional, not rational, beings. • Nor could Kant accept Hume’s dismissal of philosophy (and science, too, for that matter) as mere “melancholy and delirium.” • Kant set about to rescue both philosophy and science from the quagmire into which Hume had hurled them.