Handout 20: Hume III

advertisement

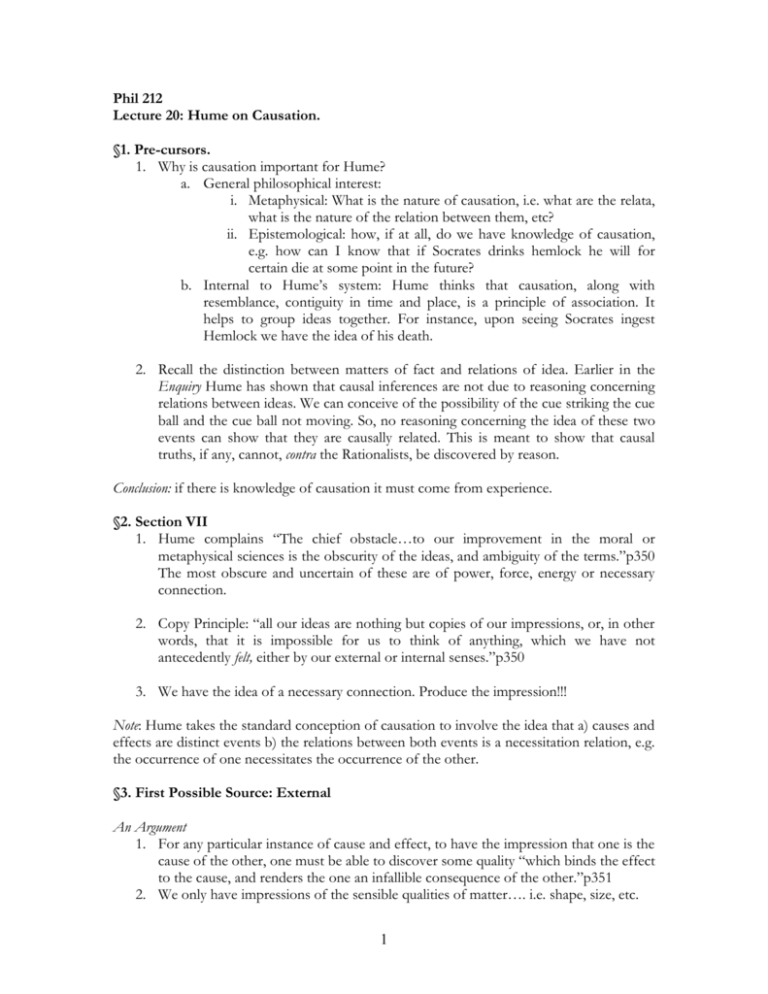

Phil 212 Lecture 20: Hume on Causation. §1. Pre-cursors. 1. Why is causation important for Hume? a. General philosophical interest: i. Metaphysical: What is the nature of causation, i.e. what are the relata, what is the nature of the relation between them, etc? ii. Epistemological: how, if at all, do we have knowledge of causation, e.g. how can I know that if Socrates drinks hemlock he will for certain die at some point in the future? b. Internal to Hume’s system: Hume thinks that causation, along with resemblance, contiguity in time and place, is a principle of association. It helps to group ideas together. For instance, upon seeing Socrates ingest Hemlock we have the idea of his death. 2. Recall the distinction between matters of fact and relations of idea. Earlier in the Enquiry Hume has shown that causal inferences are not due to reasoning concerning relations between ideas. We can conceive of the possibility of the cue striking the cue ball and the cue ball not moving. So, no reasoning concerning the idea of these two events can show that they are causally related. This is meant to show that causal truths, if any, cannot, contra the Rationalists, be discovered by reason. Conclusion: if there is knowledge of causation it must come from experience. §2. Section VII 1. Hume complains “The chief obstacle…to our improvement in the moral or metaphysical sciences is the obscurity of the ideas, and ambiguity of the terms.”p350 The most obscure and uncertain of these are of power, force, energy or necessary connection. 2. Copy Principle: “all our ideas are nothing but copies of our impressions, or, in other words, that it is impossible for us to think of anything, which we have not antecedently felt, either by our external or internal senses.”p350 3. We have the idea of a necessary connection. Produce the impression!!! Note: Hume takes the standard conception of causation to involve the idea that a) causes and effects are distinct events b) the relations between both events is a necessitation relation, e.g. the occurrence of one necessitates the occurrence of the other. §3. First Possible Source: External An Argument 1. For any particular instance of cause and effect, to have the impression that one is the cause of the other, one must be able to discover some quality “which binds the effect to the cause, and renders the one an infallible consequence of the other.”p351 2. We only have impressions of the sensible qualities of matter…. i.e. shape, size, etc. 1 3. The sensible qualities of matter are not evidence of power or energy or cause. 4. Hence, there is no impression of causal power or necessary connection in any single particular instance of cause and effect. 5. Hence, the idea of a necessary connection cannot come from an impression of a single particular instance of cause and effect. Note: Hume assumes there is an intimate relationship between causal power and necessary connections. Recall our discussion of a virtus dormitiva explanation and Boyle’s/Galileo’s worries. Observation: All we discover when we examine our impressions is that one event does follow from another. We do not discover the quality that ‘binds’ events together. “The scenes of the universe are continually shifting, and one object follows another in an uninterrupted succession; but the power or force, which actuates the whole machine, is entirely concealed from us, and never discovers itself in any of the sensible qualities of body.”p352 §4. Second Possible Source: Internal Hume considers the possibility that the idea is derived from reflection on the operations of our own mind, i.e. copied from an internal impression. He considers both the case of volition and contemplation. A. We derive the idea from being aware of internal events causing external events. e.g. I will to move my arm and my arm moves. a. Hume worries that we do not experience the power or mean by which the will moves the body. i. We do not know by what power the soul moves the body. ii. We cannot move all organs by the will, e.g. the liver. iii. We do not move our limbs directly. We move our muscles, nerves, etc. This produces movement in our limbs. We are not at all aware how they produce movement. Observation: All reflection of the will shows is that one event, an act of will, is followed by another, a particular act. For example, we experience the will willing to move the arm. We then see the arm being moved. We do not experience the relationship between these two events. B. We derive the idea from being aware of internal events causing internal events. I summon up the idea of a donkey. a. Again Hume worries that we do not experience the power by which the cause produces the effect. i. We do not know the power by which the soul could produce an idea. ii. We do not know why we have power over ideas but not other ‘internal events’ such as our passions. 2 iii. We do not know why there is such variation between say a sick person and a healthy person. Conclusion: mankind “supposes that, in all these cases, they perceive the very force or energy of the cause, by which it is connected with its effect, and is forever infallible in its operation…. [but] we only learn by experience the frequent conjunction of objects, without being ever able to comprehend anything like connection between them.” p356-357 §5. God. 1. Hume considers occasionalism, i.e. it is not a power in nature that binds causes to effect. Rather, it is the volition of a Supreme Being “who wills that such particular objects should forever be conjoined with each other.”p357 But: a. We could never know the existence of such a divine power by experience. b. We are ignorant of how God would operate on itself or on a body. §6. Hume’s Positive Proposal 1. Are our ideas of cause and effect, causal power and necessary connection all meaningless, because there are no impressions from which they can be derived? 2. NO. When we have experienced two events conjoined numerous times, there is some new impression that is developed. It is in this impression that we can derive some idea of causal power and necessary connection. What is this new impression? 3. After we experience many similar instances of similar events conjoined over and over again, when we experience a similar first event, by habit, we feel that a certain second event will follow it—the mind anticipates and forms the idea of the second event, before it occurs. This feeling is the impression from which we derive the idea of a necessary connection. “This connection, therefore, which we feel in the mind, this customary transition of the imagination from one object to its usual attendant is the sentiment or impression from which we form the idea of power or necessary connection.”p361 Hume offers two definitions of cause: 1) “we may define a cause to be an object, followed by another, and where all the objects similar to the first are followed by objects similar to the second.”p362 2) “an object followed by another, and whose appearance always conveys the thought to that other.”p362 Conclusion: causation is taken to reduce to the non-causal relations of spatiotemporal contiguity, succession and regularity between cause and effect. c causes e iff 1) c is spatiotemporally contiguous to e 2) e succeeds c in time 3 3) All events of type C (i.e. events that are like c) are regularly followed by (or are constantly conjoined with events of type E (i.e. events like e) §7. Consequences Recall the two general philosophical questions about causation above. Metaphysics: On the standard interpretation of Hume, Hume is denying that there are any necessary connections in reality. That is, he is denying that there are real causes, as traditionally construed, in reality. Epistemology: Hume is denying that we can know the causes, as traditionally construed, in reality. All I can know is that events of certain types regularly follow events of other types. §8. Aristotle’s Last Word. 1. Aristotle’s theory of causality is very different. He distinguishes four different types of causes, formal, final, efficient, material. 2. Hume claims that the two sides of the ‘causal’ relation are logically distinct events separated by temporal succession. Not so for Aristotle. For instance, the formal cause and what it is cause of are not two logically distinct events. The form of Socrates and Socrates are not obviously logically distinct. 3. Even for efficient causation, causation does not relate two logically distinct events. Rather there is one event, a change, which we experience in its totality. The sculptor sculpting is just one event. 4. It is part of Hume’s general project to show that truths about causality (if there are any) are not derived from reason, i.e. they are not known a-priori. But it is a general feature of Aristotelian science that the definition (or analysis) of P must also cite the explanation of why P occurs, e.g. a lunar eclipse. So there is no possibility of grasping the idea of P without knowing what causes it. S.O’C 4