Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13

advertisement

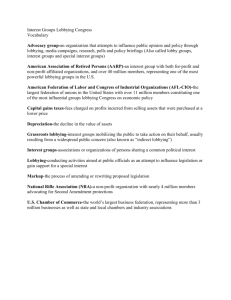

Anticorruption and the Design of Institutions 2012/13 Lecture 5 Competition and Lobbying Prof. Dr. Johann Graf Lambsdorff Literature ADI 2012/13 Lambsdorff, J. Graf (2007), The New Institutional Economics of Corruption and Reform: Theory, Evidence and Policy. Cambridge University Press: 109-135. Rose-Ackerman, S. (1999), Corruption and Government. Causes, Consequences and Reform, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press): 926. Shleifer, A. and R.W. Vishny (1993), ”Corruption.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 108: 599–617. 105 Bureaucratic Competition ADI 2012/13 One of the inspiring economic principles is that of competition. Competition is assumed to act like an invisible hand, allowing for public welfare to prosper in the absence of individuals’ social mindedness. Can competition also help fighting corruption and limiting the resulting welfare losses? Unfortunately, the answer is less straightforward. We will consecutively investigate competition among bureaucrats, politicians and private firms. 106 Bureaucratic Competition ADI 2012/13 Misusing ones office as a maximizing unit is particularly troublesome when bureaucrats are in a monopoly position. Competition between bureaucrats might drive down bribes and bring the outcome closer to the initial equilibrium. Departments could be given the right to issue licenses and permits also in areas that belong (geographically or functionally) to other departments. Their jurisdiction would overlap. This suggestion has been first proposed by Rose-Ackerman (1978: 137-166) and later labeled “overlapping jurisdiction”. This solution appears attractive when bureaucrats extort payments in exchange for licenses and permits. Payments for extortion would be reduced to zero. 107 Bureaucratic Competition ADI 2012/13 In Germany competition exists between TÜV and DEKRA on certifying car safety. Similarly between private auditors on certifying bookkeeping. Such competition can work properly if inspectors are controlled and run financial risks if misbehavior is detected. But the suggestion fails in other areas of the public sector: If misbehaving inspectors cannot be sanctioned competition would ensure that the most fraudulent bureaucrats are preferred by customers. For example, when tax collectors underreport due taxes in exchange for a bribe there might not be an independent authority that might detect the malfeasance. In public procurement contracts can be awarded only once. There is a natural monopoly in the awarding of a contract and “overlapping jurisdiction” is not applicable. 108 Political Competition ADI 2012/13 Some economic models assume benevolence among policymakers. This assumption is sometimes overemphasized. Politicians may not be primarily motivated by productive efficiency or the public interest. How does competition affect the goals pursued by politicians? Competition for votes is commonly seen to reduce corruption. This effect is parallel to that of the invisible hand in private markets: even self-seeking politicians must convince voters by effectively containing corruption among bureaucrats and among their own ranks. 109 Political Competition ADI 2012/13 Competition among politicians thus enables society to get rid of those performing poorly. Competition acts as a disciplining device. Politicians fear for their office when losing votes. This effect becomes stronger if votes are pivotal for staying in office. vote A politician‘s indifference curve 50% A political leader who loses or wins anyways is little disciplined by elections. income 110 Political Competition ADI 2012/13 However, this effect can be undermined by various forces: 1. Promises to reduce corruption may not be credible. Crucial for sound competition is not the amount of political parties, because these might be founded ad hoc and may be unable to make credible commitments. Crucial is also whether political parties have a long-standing tradition that keeps them from disappointing their voters. 2. A politician can share his corrupt income with influential actors (media, trade union leaders, senior bureaucrats) whose recommendation is estimated by voters. Honest politicians have fewer such resources at their disposal and fail to obtain the respective support. This represents another type of “political corruption”, not aimed at generating income for politicians but subverting the electoral process. 111 Political Competition ADI 2012/13 3. Another downside effect of competition relates to the subordinates (agents) of politicians (the principal). Agents may obtain bargaining power when they can choose between different principals, politicians who are standing for election. Competition may weaken politician’s control over agents (e.g. departments, regulation authorities). In return for political support politicians may turn a blind eye to bribetaking among lower levels in the public service. 112 Political Competition ADI 2012/13 Parker and Hart, December 8, 2001 113 Political Competition ADI 2012/13 Empirical results from a cross-section of countries reveal that democracy and levels of corruption do not correlate well, once regressions are controlled for income. Only those democracies that are in place for decades exhibit systematically lower levels of corruption. Investigating non-linear influences is revealing. An ambiguous impact is obtained for countries scoring between 7 and 2 in the Freedom House index. Only the good score of 1 brings about decreased corruption. Higher participation in general election is important for containing corruption. Fighting corruption by introducing political freedom is possible, but it is a thorny road where in transition corruption may even increase. 114 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 Politicians have ample opportunities to sell preferential treatment to private parties. They can protect markets by hindering competition, impose import quotas or tariffs, grant tax privileges, give subsidies, award profitable contracts, privatize industries. These activities are valuable to private parties. We call the associated value “rent”: a surplus that accrues to a firm beyond what would be needed to maintain a resource’s current service flow. Once rents are created private firms attempt to get hold of them. They compete with the help of lobbying and corruption. This type of “rent-seeking” differs from (normal microeconomic) “profitseeking” where investments into production bring about profit only if someone else is better off buying a superior product. 115 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 Wizard of ID, Parker and Hart, March 9, 2000 116 Competitive Lobbying Price ADI 2012/13 Consumer surplus with maximum price Rent Supply= Marginal Costs Dead Weight Loss Marginal Revenue 0 Q1S Demand Quantity 117 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 Only one out of n firms can win the competition for a monopolistic position created by the state, worth an exogenously given value R. The probability for winning the competition (pi) is proportional to a firm's investments into rent-seeking (xi). A single firms' probability decreases with the investments undertaken by its competitors (xj). Expenses for rent-seeking have no value to any of the firms or the state. xi pi xj , i, j = 1, ..., n j Firms are risk-neutral, face identical (profit and probability) functions and are unable to influence their competitors' level of rent-seeking xj. They maximize the expected profit, E(piR-xi). 118 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 The first order condition is: Rx i d xi x d ( pi R xi ) j dxi dxi Rx i R 1 0 2 x j x j Introducing symmetry, xi=xj=x. This brings about the Cournot-Nashequilibrium: R Rx n 1 2 2 2 1 nR R n x x 2 R nx n x n 119 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 In the case of two players, the first order condition simplifies and the following reaction function is obtained: Rx i R 2 1 0 ( x x ) R Rx ( x x ) i j i i j xi x j xi x j 2 xi x j R x j . Symmetry (xi=xj=x) brings about: R x xR x 4 x xR x x 0. 4 2 120 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 Figure 1: Rent-seeking with two players xj xi=xi(xj) R/4 xj=xj(xi) xi 0 R/4 R 121 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 x R/4 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 n n 1 S nx R n Total expenses (S) for rent-seeking then sum up to: S R 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 n 122 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 What are the consequences for welfare? The creation of rents not only distorts private markets, leading to inefficient outcomes (for example due to monopolistic dominance). There are additional costs because firms pay for bribes and lobbying. They devote resources without creating a social surplus. Devoting resources that fail to create social surplus immediately produce welfare losses – let us call them “waste”. Waste only arises in case of competition. Waste increases with the number of competitors. In case of lacking competition the monopolist can be sure to obtain the rent and will not expend these resources. 123 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 If you two behave like this while sharing every item, I'm going to unilaterally decide which state should have what! Laxman, Times of India, December 7, 2000 124 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 Corruption versus lobbying – what is the difference? Public decisions are for sale in both cases, but: As opposed to lobbying, corruption is intransparent and entails little competition. Politicians profit from corrupt payments (bribes) but not from lobbying, which may entail harassment instead. Bribes are thus a mere transfer. Only lobbying is wasteful. The conclusion by rent-seeking theory is most unusual: Corruption is better than lobbying because it entails little competition and resources are not wasted but merely transferred to politicians. 125 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 One key shortcoming of the model: Rent-seeking theory provides no adequate description for the causes of policy distortions and the creation of rents. Rent-seeking theory fails to observe that corruption can cause the creation of rents. Politicians will weight the welfare losses of the rent R against political benefits from imposing the relevant market restrictions. Thus, is competition really bad? Not necessarily when the size of rents is itself a function of rent-seeking expenses. Public servants’ will create rents (R) when they are induced to do so — primarily by bribes. 126 The Request for Bad Regulation ADI 2012/13 Office holders have an incentive to maintain the existence of rents and will oppose attempts to get rid of them. Market distortions that give rise to rents may even be initiated with the purpose of creating corrupt income. Corruption and market distortions can be two sides of the same coin. In this case the causality is reversed: Prospects of corrupt income can be responsible for the creation of market distortions and rents. An office holder then regards his office as a business, the income of which he will seek to maximize. 127 The Request for Bad Regulation ADI 2012/13 In return for the exclusive right to import gold, a private businessperson offered bribes to the Pakistani government. In 1994 the payment of US $ 10 million on behalf of Ms Bhutto's husband was arranged and a license to be the country's sole authorized gold importer was granted. The Abacha family was behind the operations of the firm of Delta Prospectors Ltd., which mines barite, an essential material for oil production. Shortly after Delta's operations had reached full production, General Abacha banned the import of barite, turning the company into a monopoly provider. 128 The Request for Bad Regulation ADI 2012/13 Allegations concerning a son of the minister of the interior in Saudi Arabia: he established a chain of body shops for car repairs. Afterwards he engaged his father to obtain a decree by the king, imposing a requirement for the annual inspection of all 5 million cars registered in Saudi Arabia. Twin currency system in South Africa was officially aimed at providing foreign currency to investors. But the parliamentary commission entitled to distribute the cheaper currencies was said to request favors in exchange. Abolishing this system was long impeded by the commission's influence on parliament. 129 The Request for Bad Regulation ADI 2012/13 Look, I want to announce some rigid rules and regulations — so that I may liberalise them to give relief to the people! Laxman, Times of India 130 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 The positive impact of rent-seeking expenses (S) on the rent (R) will be felt more when few competitors exist. For competing firms the overall size of the rent is a public good which they will hardly lobby for. For a monopolist the total rent is not a public good but his own private good. A monopolist may thus be willing to devote resources to rentseeking activities. As opposed to lobbying, corruption is more forceful in motivating distorting rents. 131 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 Finally, lobbies represent “broader” interests while corruptors represent only their own interest. A rent created for broad interests will have more difficulties organizing a joint willingness to pay. Such rents are thus less likely to be generated with a corrupt intention. Overall, lobbying is more transparent and includes broader segments of society. It can represent a form of participation where not narrow defined interests are exchanged but responsibility for broader interests emerges. The idea that corruption is better than lobbying can be misleading. o Lobbies have an interest in reducing the disorganized bribery by their members. o Lobbies can help in ordering communication between business and politics. o The behavior of all lobbies might be further improved by registration, accountability and codes of conduct for lobbies and their representatives. 132 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 Lobbies face organizational difficulties: they strive to obtain a rent for a whole sector, even if the individual firms do not contribute to the functioning of the lobby. Members face a prisoner’s dilemma, which may hinder the foundation and functioning of a lobby. Is this good or bad? Some researchers argue that this is good, because lobbies intervene in otherwise undistorted decisions. I would argue that it is bad, because lobbies balance the various interests of their members to form broader interest that are pursued transparently; only those striving for narrow interests will survive if lobbies are hindered. 133 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 Independent courts and Presidents with veto power restrict the parliament’s capacity to “sell” laws. Courts have discretionary power in interpreting law; courts check the consistency of laws against older legislation and the constitution, setting preferences in case of conflict; courts have the power to reject the enforcement of new laws. In case of a veto power, two parties must be paid for passing favorable laws. Both institutions introduce continuity in the otherwise unbound and potentially arbitrary laws enacted by parliament. Are veto powers helpful in containing corruption? 134 Competitive Lobbying ADI 2012/13 Some would argue that this is bad, because the value of rents increases. Laws, once passed, assign long-term income streams to those who were able to influence legislation in their favor. The judiciary helps to enforce the 'deals' made by effective interest groups with earlier legislatures. I would argue, instead, that this is good. Laws that are valid over a longer period will be fought for by larger lobbies which promote broader interests. Quickly changing laws and ad hoc decisions are lobbied for by those striving for narrow interests. Still, the overall judgment on the usefulness of veto powers is more complex, in particular, because there might be intransparent collusion among veto powers. 135 Appendix ADI 2012/13 Discussions 1) What is the concept of “overlapping jurisdictions”? Where may it help in reducing corruption, where not? 2) Does competition for political positions increase or decrease corruption? Explain the diverging positions! 3) What is rent-seeking as opposed to profit-seeking? 4) What determines the extent of “waste”? 5) Why is competition regarded to be harmful by rent-seeking theory? 6) Why is competition for rents not as bad as suggested by rent-seeking theory? 7) What are the pros and cons of independent courts and political veto powers? 136 Appendix ADI 2012/13 8) On June 20, 2001, Reuters ran the following news: …Argentina now has two exchange rates -- one for domestic transactions that Argentines will use when they buy groceries or pay rent where one peso equals one dollar, and another for trade that applies only to exporters and importers. Under this new system, for instance, a grain exporter would receive 1.0748 pesos for every dollar sold abroad, raising the grain exporter's revenues and making his goods more competitive in markets like Brazil and Europe. But experts say the measure -- which amounts to a 7 percent subsidy for exports and a tax on imports -- is a form of capital control that creates massive opportunities for corruption. Discuss how this system may have developed if a) the government is benevolent, b) the government is naïve and driven by interests of lobbies, c) if the government is maximizing! 137 Appendix ADI 2012/13 Exercise Three firms compete for a monopoly license for gambling. The total rent is US$ 180 Mio. a) One firm assumes that each of its competitors will spend US $ 10 Mio. for bribes and lobbying. Determine its optimum probability to win the contest, assuming that its probability to win the contest is proportional to its own rentseeking expenses, divided by all firms’ expenses! b) If all firms expect their competitors to optimize their rent-seeking expenses (Cournot-Nash solution), how much will each spend for this purpose? c) Rent-Seeking theory concludes total rent-seeking expenses increase with the number of firms. What is the economic reason for this conclusion? d) Why may this relationship not arise in reality? 138