3 sources

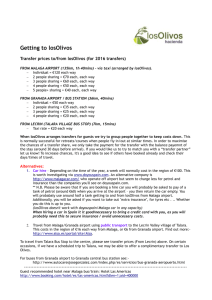

advertisement

Self-Governing Muslims of Medieval Spain 1240 to 1327Conquered Moors of Al-Andalus had special status and were permitted to have their own communities and courts. According to a treaty in 1492, the Moors were to be allowed to preserve their mosques and religious institutions, to retain their language and to continue to abide by their own laws and customs. Within seven years these terms were broken. Cardinal Cisneros When the moderate archbishop of Granada, Hernando de Talavera was replaced by the fanatical Cardinal Cisneros (c.1436-1518) mass conversions and the burning of all religious texts in Arabic were organised. In 1582 expulsion of the Moors (Moriscos) as well as Jews from Spain was proposed but no action was taken until 1609-10 when edicts of expulsion dictated at every stage by the Church were decreed. An estimated 600,000 Moriscos were deported. The decision to proceed was approved unanimously by the Council of State in 1608 and the Spanish fleet was secretly prepared later to be joined by many foreign merchant ships, including several from England. An estimated 600,000 Moriscos from Aragon, Castile, Andalusia were forcibly evicted from Spain and went to Oran, Tunis, Tlemcen, Tetuán, Rabat and Salé, Italy, Sicily or Constantinople The decision to proceed was approved unanimously by the Council of State in 1608 and the Spanish fleet was secretly prepared later to be joined by many foreign merchant ships, including several from England. An estimated 600,000 Moriscos from Aragon, Castile, Andalusia were forcibly evicted from Spain and went to Oran, Tunis, Tlemcen, Tetuán, Rabat and Salé, Italy, Sicily or Constantinople The French demographer Henri Lapeyre estimated from census reports and embarkation lists that approximately 275,000 Spanish Moriscos emigrated in the years 1609-14, out of a total of 300,000. This conservative estimate is not consistent with many of the contemporary accounts that give a figure of 600,000. Bearing in mind that the total population of Spain at that time was only about seven and a half million, this must have constituted a serious deficit in terms of productive manpower and tax revenue. In the Kingdom of Valencia, which lost a third of its population, nearly half the villages were deserted in 1638. When the moderate missionary approach of the archbishop of Granada, Hernando de Talavera (14281507), was replaced by the fanaticism of Cardinal Cisneros (c.1436-1518), who organised mass conversions and the burning of all religious texts in Arabic, these events resulted in the First Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1499-1500) and the assassination of one of the Cardinal’s agents. This in turn gave the Catholic monarchs an excuse to revoke their promises. Iberia and Al-Andalus in the late 15th century See also: Reconquista The five kingdoms of Iberia in 1360. The territory of the Emirate of Granada was reduced by 1482, as it lost its grasp on Gibraltar and other western territories. The Emirate of Granada had been the sole Muslim state in Al-Andalus - Iberia - for more than a century by the time of the Granada War. The other remnant states of the Caliphate of Córdoba (taifa) had already been conquered by the Reconquista. Pessimism for Granada's future existed even then; in 1400, Ibn Hudayl wrote "Is Granada not enclosed between a violent sea and an enemy terrible in arms, both of which press on its people day and night?"[1] Still, Granada was wealthy and powerful, and the Christian kingdoms were divided and fought amongst themselves. Granada's problems began to worsen after Emir Yusuf III's death in 1417. Succession struggles made it such that Granada was in an almost constant low-level civil war. Loyalty to clan was stronger than that to the Emir, making consolidation of power difficult. Often, the only territory the Emir really controlled was the city of Granada itself. At times, the emir did not even control all the city, but rather one emir would control the Alhambra, and another the Albaicín, the most important district of Granada.[2] This internal fighting greatly weakened the state. The economy declined, with Granada's once world-famous porcelain now disrupted and challenged by Manises near Valencia. Taxes were still imposed at their earlier high rates to support Granada's extensive defenses and large army, despite the weakening economy. Ordinary Granadans paid triple the taxes of (non-tax-exempt) Castilians.[2] The heavy taxes that Emir Abu-l-Hasan Ali (1464–85) imposed contributed greatly to his unpopularity. These taxes did at least support a respected army; Hasan was successful in putting down Christian revolts in his lands, and some observers estimated he could muster as many as 7,000 horsemen. [3] The frontier between Granada and Andalusia was in a constant state of flux, "neither in peace nor in war."[3] Raids across the border were common, as were intermixing alliances between local nobles on both sides of the frontier. Relations were governed by occasional truces and demands for tribute should one side have been seen to overstep their bounds. Neither country's central government intervened or controlled the warfare much.[3] King Henry IV of Castile died in December 1474, setting off the War of the Castilian Succession between Henry's daughter Juana la Beltraneja and Henry's half-sister Isabella. The war raged from 1475–1479, setting Isabella's supporters and the Crown of Aragon against Juana's supporters, Portugal, and France. During this time, the frontier with Granada was practically ignored; the Castilians did not even bother to ask for or obtain reparation for a raid in 1477. Truces between the sides were agreed upon in 1475, 76, and 78. In 1479, the Succession War concluded with Isabella victorious. As Isabella had married Ferdinand of Aragon in 1469, this meant that the two powerful kingdoms of Castile and Aragon would now stand united, free from inter-Christian war which had helped Granada survive.[4] Ar-Rundi might well have been responding to the plight of his co-religionists after the fall of Granada or at the time of the expulsion when many similar atrocities were committed: homes were destroyed and abandoned, mosques were converted into churches, mothers were separated from their children, people were stripped of their wealth and humiliated, armed rebels were reduced to slavery. But by the seventeenth century the Moors had become Spanish citizens; some were genuine Christian converts; indeed many, like Sancho Panza’s neighbour Ricote in Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote (1605-15), were deeply patriotic and considered themselves to be ‘más cristiano que moro’. Yet all were the victims of a state policy, based on racist theological arguments, which had the backing of both the Royal Council and the Church, for which the expulsion of the Jews in 1492 provided an immediate legal precedent. According to the terms of the treaty drawn up in 1492, the new subjects of the Crown were to be allowed to preserve their mosques and religious institutions, to retain the use of their language and to continue to abide by their own laws and customs. But within seven years these terms had been broken. When the moderate missionary approach of the archbishop of Granada, Hernando de Talavera (14281507), was replaced by the fanaticism of Cardinal Cisneros (c.1436-1518), who organised mass conversions and the burning of all religious texts in Arabic, these events resulted in the First Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1499-1500) and the assassination of one of the Cardinal’s agents. This in turn gave the Catholic monarchs an excuse to revoke their promises. In 1499 the Muslim religious leaders of Granada were persuaded to hand over more than 5,000 priceless books with ornamental bindings, which were then consigned to the flames; only some books on medicine were spared. In Andalusia after 1502, and in Valencia, Catalonia and Aragon after 1526, the Moors were given a choice between baptism and exile. For the majority, baptism was the only practical option. Henceforward the Spanish Moors became theoretically New Christians and, as such, subject to the jurisdiction of the Inquisition, which had been authorised by Pope Sixtus IV in 1478. For the most part, conversion was nominal: the Moors paid lip-service to Christianity, but continued to practise Islam in secret. For example, after a child was baptised, he might be taken home and washed with hot water to annul the sacrament of baptism. The former Muslims were able to lead a double life with a clear conscience because certain Islamic religious authorities ruled that, under duress or threat to life, Muslims might apply the principle of taqiyyah or precaution that made dissimulation and hypocrisy permissible. In response to a plea from the Spanish Muslims, the Grand Mufti of Oran, Ahmad ibn Abu Juma’a, issued a decree in 1504, in which he stated that Muslims may drink wine, eat pork or do any other forbidden thing if they are compelled to do so and if they do not have the intention to sin. They may even, he said, deny the Prophet Muhammad with their tongues provided, at the same time, they love him in their hearts – though not all Muslim scholars agreed with this advice. Thus the fall of Granada marked a new phase in MuslimChristian relations. In medieval times the status of Muslims under Christian rule was similar to that of Christians under Muslim rule: they belonged to a protected minority which preserved its own laws and customs in return for tribute. But there was no Scriptural basis for the legal status of Jews and Muslims under Christian rule; they were subject to the whims of rulers, the prejudices of the populace and the objections of the clergy. Before the completion of the Reconquest it was in the interests of the kings of Aragon and Castile to respect such laws and contracts. Now, however, Spain not only became, at least in theory, an entirely Christian nation but purity of faith came to be identified with purity of blood so that all New Christians or conversos, whether of Jewish or Muslim origin, were branded as potential heretics. As a member of a vanquished minority with an alien culture, the moro became a morisco, a ‘little Moor’. Every aspect of his way of life – including his language, dress and social customs – was condemned as uncivilised and pagan. A person who refused to drink wine or eat pork might be denounced as a Muslim to the Inquisition. In the eyes of the Inquisition and popular opinion, even practices such as eating couscous, using henna, throwing sweets at a wedding and dancing to the sound of Berber music, were un-Christian activities for which a person might be obliged to do penance. Moriscos who were sincere Christians were also bound to remain second-class citizens, and might be exposed to criticism from Muslims and Christians alike. Although morisco is a derogatory term, historians find it a useful label for those Arabs or Moors who remained in Spain after the fall of Granada. In 1567 Philip II renewed an edict which had never been strictly enforced, making the use of Arabic illegal and prohibiting Islamic religion, dress and customs. This edict resulted in the Second Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1568-70), which seemed to corroborate evidence of a secret conspiracy with the Turks. The uprising was brutally suppressed by Don John of Austria. One of his worst atrocities was to raze the town of Galera, to the east of Granada, and sprinkle it with salt, having slaughtered 2,500 people including 400 women and children. Some 80,000 Moriscos in Granada were dispersed to other parts of Spain and Old Christians from northern Spain were settled on their lands. By 1582 expulsion was proposed by Philip II’s Council of State as the only solution to the conflict between the communities, despite some concern about the harmful economic repercussions – the loss of Moorish craftsmanship and the shortage of agricultural manpower and expertise. But as there was opposition from some noblemen and the King was preoccupied by international events, no action was taken until 1609-10 when Philip III (r.1598-1621) issued edicts of expulsion. Royal legislation concerning the Moriscos was dictated at every stage by the Church. Juan de Ribera (1542-1611), the aging Archbishop of Valencia, who had initially been a firm believer in the efficacy of missionary work, became in his declining years the chief partisan of expulsion. . In a sermon preached on September 27th, 1609, he said that the land would not become fertile again until these heretics had been expelled. The Duke of Lerma (Philip III’s first minister, 1598-1618) also underwent a change of heart when it was agreed that the lords of Valencia would be given the lands of the expelled Moriscos in compensation for the loss of their vassals. The decision to proceed with the expulsion was approved unanimously by the Council of State on January 30th, 1608, although the actual decree was not signed by the King until April 4th, 1609. Galleons of the Spanish fleet were secretly prepared, and they were later joined by many foreign merchant ships, including several from England. n September 11th, the expulsion order was announced by town criers in the Kingdom of Valencia, and the first convoy departed from Denia at nightfall on October 2nd, and arrived in Oran less than three days later. The Moriscos of Aragon, Castile, Andalusia and Extremadura received expulsion orders during the course of the following year. The majority of the forced emigrants settled in the Maghrib or Barbary Coast, especially in Oran, Tunis, Tlemcen, Tetuán, Rabat and Salé. Many travelled overland to France, but after the assassination of Henry of Navarre by Ravaillac in May 1610, they were forced to emigrate to Italy, Sicily or Constantinople. There is much disagreement about the size of the Morisco population. The French demographer Henri Lapeyre estimated from census reports and embarkation lists that approximately 275,000 Spanish Moriscos emigrated in the years 1609-14, out of a total of 300,000. This conservative estimate is not consistent with many of the contemporary accounts that give a figure of 600,000. Bearing in mind that the total population of Spain at that time was only about seven and a half million, this must have constituted a serious deficit in terms of productive manpower and tax revenue. In the Kingdom of Valencia, which lost a third of its population, nearly half the villages were deserted in 1638. •Home •Create a Timeline myspacediggfacebooktwitter •Hot Topics Show/Hide Sources •Dipity Premium 3 sources - 160 events 15/12/1868 Following a civil war in Japan in which the shogun lost, his supporters fled to the Northernmost island where the proclaimed a republic and held the first modern elections in Japan's history. The government was based on the United States and was established with the help of the French and British. •Chinese People Revolt Again 1867 stumbleupon Global Democracy Resource4715 ViewsShare: Despite being overstretched by the vast number and widely distributed acts of rebellion, the Qing Dynasty Imperial forces manage to suppress the nearly two decade Nien Rebellion. The Ever Victorious Army as they were unfortunately called would be overcome in due time. •Secret Ballot 07/02/1856 Ancient democracies such as Athens had means of secret voting to prevent intimidation and bribery. During the European Middle Ages, the norm became the large meeting at the town hall so democracy became intentionally a public act. The modern nation-state demanded a return to secret voting. The French and Dutch republics were early reformers, but the secret or "Australian ballots" introduced in Tasmania have been used ever since and have been adopted by the rest of the democratic world. •Miners Demand Real Democracy 11/11/1854 Australia was established by a British corporation as prison. This hardly seems to be a recipe for democracy, but the land down under quickly developed strong democratic traditions. Workman rebelled at the Eureka Stockade after the police murdered one of their own. They counted full male suffrage among the main demands. The were violently suppressed but their progressive dreams quickly became the norm in the Western world. •Year of World Revolution 1848 Economic and political disturbances erupt from Texas to Brazil to Sri Lanka and nearly every country of Europe. The seemingly impossible fulfilment of all of the democratic dreams of that time caused French author Proudhon to lament the "year democracy slipped from our hands", but several very substantial democratic reforms where achieved during that time including the elimination of serfdom by the Habsburgian Empire and the establishment of the most democratic nation-state known until that time in Switzerland. •O Progresso 01/01/1848 Inspired by similar efforts throughout the world, the people of in Pernambuco on the fringes of the Brazilian Empire revolt. Their "Manifesto to the World" demands free and universal voting rights, freedom of the press, federalism and the end of the "Poder Moderador” (supremacy of the emperor over the executive, legislative, and judiciary). •Theodemocracy 11/03/1844 American farmboy, Joseph Smith, had a series of visions that led to the establishment of a new religion. The Mormons were both a belief system and a governance system. The leaders wished to combine the best aspects of democracy and moral guidance and established the Council of 50. These believers left in search of a safe home when Joseph smith was assassinated, eventually settling in the Utah Valley. They ran the "far flung commonwealth" on their own until rumors spread in the American East about a religious rebellion. The U.S. Army brought the land of Utah into territorial status. The state today remains a majority of Mormons. •Young Italy 1841 As Europe and the Americas entered the Modern Industrial Age, Italy was still a fractured country. France, the pope, and the Hapsburgian Empire controlled large parts of what is now Italy. This situation plus the revolutions raging throughout the rest of Europe resulted in a secret society called the Carbonari (coal carriers). Because it is secret, it is unknown when and where it was founded, but by the 1820s and 1830s, these carbonari were involved in revolutionary activity in France, Portugal, Sardinia, and elsewhere. They reformed as "Young Italy", which was involved in uprisings throughout Italy all the way up to the formation of the modern state of Italy in 1860. We have chosen the revolt in ancient university town of Bologna as our map-timeline point, but other interesting examples were the temporary reforming of the Roman and Venetian Republics in 1848. •Heavenly Kingdom 1837 While desperately studying for a civil service exam in China with a pass rate of only 1%, Hong Xiuquan of Southern China hears a Christian preaching. He failed the exam and had a series of visions. He considered himself the brother of Christ, and started to convert the poor minorities in the country-side ... as well as the many bandits and pirates. When their numbers swelled to 30000, they revolted and established a 'heavenly kingdom' on Earth based in Nanjing. •Paris Burns Again Jul 1830 The fallout from the Congress of Vienna was quick: The revolted against the reinstated royal house, and replaced it with the constitutional "July Monarchy". The Belgians revolted against the House of Orange the next month. •We Came Here in Search of Freedom 1822 The African state of Liberia is one of the many places that derives its name from freedom. The state was founded by freed slaves repatriated to Africa. In the middle of the 19th Century it started to enjoy some quasi-independence from the U.S., but many problems still existed with tensions with the indigenous Africans. As recently as 2003 there were bloody wars being fought, and the exPresident is on trial for crimes against humanity. This warm and wet land had re-earned its noble name by peacefully and democratically electing a new president in 2007 -- the first female elected African head of state in modern times. •Democracy Returns to Athens 25/05/1821 Source Status Ken Kostyo - 150 UserEv events ents Freedo 2 mwrigh events t story of 8 freedo events m