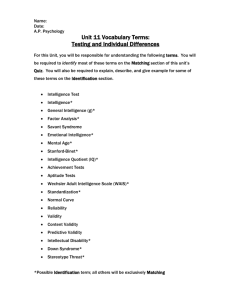

Powerpoint slides for Chapter 8

advertisement

5th Edition Psychology Stephen F. Davis Emporia State University Joseph J. Palladino University of Southern Indiana PowerPoint Presentation by Cynthia K. Shinabarger Reed Tarrant County College This multimedia product and its contents are protected under copyright law. The following are prohibited by law: any public performance or display, including transmission of any image over a network; preparation of any derivative work, including the extraction, in whole or in part, of any images; any rental, lease, or lending of the program. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-1 Chapter 8 5th Edition Thinking, Language, and Intelligence Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-2 Thinking • Cognitive psychology is a branch of psychology that examines thinking: how we know and understand the world, solve problems, make decisions, combine information from memory and current experience, use language, and communicate our thoughts to others. • Thinking is a mental process involving the manipulation of information in the form of images or concepts that is inferred from our behavior. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-3 Thinking • Many people report that they visualize events and objects to answer some types of questions. • Visual imagery, the experience of seeing even though the event or object is not actually viewed, can activate brain areas responsible for visual perception, such as the occipital lobes. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-4 Thinking • Concepts are mental categories that share common characteristics. • We usually identify specific examples as members of a concept by judging their degree of similarity to a prototype, or best example, of the concept. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-5 Thinking • Every day we encounter a variety of minor problems; occasionally we face major ones. • Problems can differ along several dimensions; for example, some are well defined or structured, and others are ill defined or unstructured. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-6 Thinking • Well-defined problems have three specified characteristics: – a clearly specified beginning state (the starting point), – a set of clearly specified tools or techniques for finding the solution (the needed operations), and – a clearly specified solution state (the final product). Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-7 Thinking • Ill-defined problems have a degree of uncertainty or “messiness” about the starting point, needed operations, and final product. • Such problems can have numerous acceptable responses, and the criteria for judging the responses are not necessarily simple and straightforward. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-8 Thinking • One strategy you could use to solve some problems guarantees a correct solution in time (provided that a solution exists). • An algorithm is a systematic procedure or specified set of steps for solving a problem, which may involve evaluating all possible solutions. • Algorithms can be time-consuming and do not work for problems that are not clearly defined. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-9 Thinking • Heuristics are educated guesses or rules of thumb that are used to solve problems. • Although the use of heuristics does not guarantee a solution, it is more timeefficient than using algorithms. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-10 Thinking • Researchers have compared the problem solving of experts and nonexperts and have found that experts know more information to use in solving problems. • More important, experts know how to collect and organize information and are better at recognizing patterns in the information they gather. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-11 Thinking • Psychologists have found that expert problem solvers are adept at breaking problems down into subgoals, which can be attacked and solved one at a time. • These intermediate subgoals can make problems more manageable and increase the chance of reaching a solution. • Information that is not organized effectively can hinder problem solving. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-12 Thinking • Rigidity is the tendency to rely on past experiences to solve problems. • One form of rigidity, functional fixedness, is the inability to use familiar objects in new ways. • Set effect is a bias toward the use of certain problem-solving approaches because of past experience. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-13 Thinking • A common mistake in testing hypotheses is to commit to one hypothesis without adequately testing other possibilities; this is known as confirmation bias. • When we use the representativeness heuristic, we determine whether an event, an object, or a person resembles (or represents) a prototype. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-14 Thinking • The availability heuristic involves judging the probability of events by the readiness with which they come to mind. • We often make decisions by comparing the information we have obtained to some standard. • Your standards are constantly changing, and these changes can affect your judgments. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-15 Thinking • When we make decisions, we are also influenced by whether our attention is drawn to positive or negative outcomes; psychologists refer to this presentation of an issue as framing. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-16 Thinking • Creativity is the ability to produce work that is both novel and appropriate. • There is no absolute standard for creativity. • Intelligence tests were not designed to measure creativity, so it is not surprising that the correlation between measures of creativity and intelligence is weak to moderate. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-17 Thinking • Creativity depends on divergent thinking, rather than the convergent thinking assessed in tests of intelligence. • When all lines of thought converge on one correct answer, we have an example of convergent thinking. • By contrast, divergent thinking takes our thinking in different directions in search of multiple answers to a question. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-18 Thinking • Creativity typically involves seeing nontypical, yet plausible, ways of associating items or seeing aspects of an item that are real and useful, but not usually the primary focus of our attention. • Creative people are not afraid of hard work; they give it their undivided attention and persevere in the face of obstacles. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-19 Thinking • Another mark of a creative person is a willingness to take risks and expose oneself to the potential for failure. • What’s more, creative people tolerate ambiguity, complexity, or a lack of symmetry. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-20 Thinking • Creativity often emerges when we rearrange what is known in new and unusual ways that can yield creative ideas, goods, and services. • A task-focusing motivator energizes a person to work and keeps the person’s attention on the task. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-21 Thinking • By contrast, a goal-focusing motivator leads a person to focus attention on rewards such as money to the detriment of the task. • Creativity often flourishes with the right mix of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-22 Thinking • The business community is interested in enhancing creativity to develop and market products and services. • There is no magic in enhancing creativity; it takes the right attitude and technology in a work climate that is receptive to creative thinking and new ideas. • Among the other important organizational influences on creativity is encouragement of risk taking, generating ideas, and sharing ideas. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-23 Thinking • Adults are expected to be serious, yet playfulness and humor can help develop flexible thinking. • Injecting humor and playfulness into the work situation can stimulate a creative mind set, including the use of games and puzzles designed to enhance creativity. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-24 Thinking • Quite often people fail to develop creative ideas because they do not believe they can be creative. • The first step in developing one’s creativity is to acknowledge and confront these negative thoughts and replace them with positive thoughts. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-25 Thinking • Creativity consultants aim to inject change into the lives of employees. • They encourage employees to break habits by taking a different route to work, listening to a different radio station, or reading different magazines. • These minor changes help employees break out of a rut, expose them to new ideas, and get them thinking rather than operating on automatic pilot. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-26 Language • Between birth and the beginning of formal schooling, children learn to speak and understand language. • Speech is what people actually say; language is the understanding of the rules of what they say. • Acquiring any of the approximately 4,000 languages is a remarkable accomplishment because there is so much to learn. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-27 Language • Phonemes are unique sounds that can be joined to create words. • Phonemes are the building blocks of language. • A morpheme is the smallest unit of language that has meaning. • When we learn to organize words into phrases and sentences, we are acquiring what is called syntax. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-28 Language • No matter what language their parents speak (and even if the parents are deaf), babies make the same sounds at about the same time. • At about 2 months of age, an infant begins cooing. • At about 6 months of age, infants begin babbling, making one-syllable speech-like sounds that usually contain both vowels and consonants but have no meaning. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-29 Language • Toddlers who hear English at home will utter their first word that conveys meaning at about 1 year. • Vocabulary development continues at a rapid pace during the preschool years. • Psychologists are especially interested in three characteristics of the infant’s language. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-30 Language • First, young children often use telegraphic speech—they leave words out of sentences, as in a telegraph message. • Second, children seem to know how to string words together to convey the intended meaning in the correct sequence for their language. • Third, children often overgeneralize grammatical rules, so the plural of mouse should be mouses! Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-31 Language • According to behaviorists, language is learned like other behaviors: through imitation, association, and reinforcement. • According to the nativist theory of language, children are innately predisposed to acquire language. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-32 Language • The major advocate of this position, Noam Chomsky, has called this innate ability our language acquisition device (LAD). • Most psychologists favor a combination of learning and nativist theories. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-33 Language • When we think of a language, we often think of an oral-auditory one—that is, one that is heavily dependent on audition. • Not all languages fit this category, however. • A prominent example is American Sign Language (ASL) or Ameslan, a manual-visual language developed within the American deaf community that is distinct from oral-auditory languages. • ASL is not a signed version of English; it is unique, separate, and distinct from English, with its own grammar and syntax. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-34 Language • People who use ASL communicate rapidly via thousands of manual signs and gestures. • Words are assembled from hand shapes, hand motions, and the positions of the hands in front of the body. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-35 Language • The linguistic relativity hypothesis suggests that syntax (word order) and vocabulary can mold thinking. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-36 Language • There are many current examples of the use of language to influence and control thinking. • The use of language by business, educational, and governmental organizations can mislead or control perception and thinking. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-37 Language • The term doublespeak describes language that is purposely designed to make the bad seem good, to turn a negative into a positive, or to avoid or shift responsibility. • One form of doublespeak is the euphemism, an acceptable or inoffensive word or phrase used in place of an unacceptable or offensive one. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-38 Language • The word he may not be intended to convey whether the person is a man or a woman, but most people assume the speaker meant that the person was a man. • The words he, his, and man refer to men, but they are often also used to encompass both men and women. • These examples demonstrate how the words we use can guide our thinking, perhaps in ways we had not intended or recognized. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-39 Intelligence • A psychological test is an objective measure of a sample of behavior that is collected according to well-established procedures. • They are composed of observations made on a small, but carefully chosen sample of a person’s behavior. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-40 Intelligence • Such tests are used for a range of purposes, including measuring differences among people in characteristics such as intelligence and personality. • The primary purpose of one of the first psychological tests was to identify children with below-average intellectual ability so that they could be given schooling designed to improve that ability. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-41 Intelligence • How a person defines intelligence depends on whom we ask, and the answers differ across time and place. • Thus, what behaviors are perceived as examples of intelligent behavior is influenced in part by culture. • The Japanese place greater emphasis on the process of thinking than people in the United States. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-42 Intelligence • In Africa, conceptions of intelligence focus on skills that facilitate and maintain harmonious group relations. • The definition of intelligence used in Western cultures, especially the United States, does not necessarily match definitions used in other parts of the world. • We can define intelligence as the overall ability to excel at a variety of tasks, especially those related to success in schoolwork. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-43 Intelligence • We can trace the study of differences in intelligence to an Englishman, Sir Francis Galton. • Galton believed that heredity was responsible for human differences in intelligence and ability. • Galton contended that eminence and creativity run in families because they are inherited characteristics; he dismissed the potential influence of environmental factors. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-44 Intelligence • Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon developed an intelligence test to evaluate French schoolchildren. • They proposed the concept of mental age which compared a child's performance with the average performance of children at a particular age. • The intelligence quotient (IQ) is the ratio of mental age divided by chronological age and multiplied by 100. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-45 Intelligence • David Wechsler developed an intelligence test for adults. • Scores on this test are calculated by comparing a person’s score with scores obtained by people of a range of ages rather than a single age. • The current version of this test, known as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III), is used to assess people between the ages of 16 and 74. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-46 Intelligence • Wechsler’s scales have also been adapted to assess intelligence at earlier ages. • The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale and the Wechsler intelligence tests are individual tests (one person is tested at a time) that must be administered by a qualified examiner. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-47 Intelligence • The three characteristics of a good psychological test are reliability, validity, and standardization. • Reliability is the degree to which repeated administrations of a psychological test yield consistent scores. • Validity refers to a test's ability to measure what it was designed to measure. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-48 Intelligence • Standardization refers to the development of procedures for administering psychological tests and the collection of norms that provide a frame of reference for interpreting test scores. • Norms are the distribution of scores of a large sample of people who have previously taken a test. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-49 Intelligence • Intelligence test scores are distributed in the shape of a bell curve. • The majority of the scores are clustered around the middle, with fewer scores found at either extreme. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-50 Intelligence • Intelligence test scores below 70 or above 130 occur in less than 5% of the population; people with such statistically rare scores are designated as exceptional. • Those with scores below 70 may be diagnosed as mentally retarded if they also exhibit significant deficits in everyday adaptive behaviors, such as self-care, social skills, or communication. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-51 Intelligence • Public Law 94-142 (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, IDEA), includes provisions for educating all children with handicaps. • Standard intelligence tests such as the WISC-III are frequently used in the evaluation of children who are perceived as exceptional. • Exceptional children often require special attention and services, but there is no standard approach to dealing with their needs. • People with IQ scores of about 140 and above may be identified as gifted. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-52 Intelligence • Savant syndrome occurs in people who are severely handicapped in overall intelligence yet demonstrate exceptional ability in a specific area such as art, calculation, memory, or music. • Most savants are male; the syndrome occurs in approximately one in 2,000 people with brain damage or mental retardation and about 1 in 10 people with autism. • Accumulating evidence suggests that people with savant syndrome have suffered damage to the left hemisphere, which apparently results in some form of compensation by the right hemisphere. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-53 Intelligence • Charles Spearman believed that there are two types of intelligence, one called g for general intelligence and the other, representing a number of specific abilities, called s. • Robert Sternberg proposed the triarchic theory of intelligence. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-54 Intelligence • This model is comprised of: a) analytical intelligence, or the ability to break down a problem or situation into its components (the type of intelligence assessed by most current intelligence tests); b) creative intelligence, or the ability to cope with novelty and to solve problems in new and unusual ways; and c) practical intelligence, which is also known as common sense or “street smarts.” Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-55 Intelligence • The third type of intelligence is one that the public understands and values, yet it is missing in standard intelligence tests. • The triarchic theory on intelligence emphasizes the processes of intelligence. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-56 Intelligence • To account for the broad range of achievements in modern society, Howard Gardner proposes the existence of “a number of relatively autonomous intellectual capacities or potentials” he calls multiple intelligences. • According to Gardner, there is more to intelligence than the verbal and mathematical abilities measured by current intelligence tests. • Each person may have different strengths and weaknesses and thus may manifest intelligence in various ways. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-57 Intelligence • The high reliability coefficients that characterize most intelligence tests should not lead to the incorrect conclusion that assessments based on such tests are always accurate (valid). • The eugenics movement proposed that the intelligence of an entire nation could be increased if only the more intelligent citizens had children. • Intelligence test scores have been used to prevent some European immigrants from entering the United States. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-58 Intelligence • The heritability of intelligence is an estimate of the influence of heredity in accounting for differences among people. • The heritability of intelligence tends to increase with age. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-59 Intelligence • Yet, even clearly inherited conditions, such as PKU, can be modified by altering a person's environment. • Although PKU has a heritability of 100%, it can be modified by changing the environment (in this case, diet). • In short, heredity is not necessarily destiny. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-60 Intelligence • Correlations between the IQ scores of identical twins suggest that intelligence is strongly influenced by heredity. • When twins are raised in separate environments, the correlation between their intelligence scores is still high. • The intelligence scores of adopted children tend to correlate more highly with those of their biological parents than with those of their adoptive parents. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-61 Intelligence • The closer the family relationship, the higher the correlation between the intelligence scores of family members. • Studies of adopted children suggest that environmental factors also have an effect on intelligence. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-62 Intelligence • In the 1930s, Howard Skeels decided that tender, loving care, and stimulation could be beneficial for two children in an Iowa orphanage. • Skeels placed these quiet, slow, unresponsive sisters in a home for mentally retarded adolescents. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-63 Intelligence • On his return several months later, he was surprised to find that the sisters’ intelligence test scores had increased and that they appeared alert and active. • The attention and stimulation provided by the mentally retarded adolescents and the staff of the institution had made a difference. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-64 Intelligence • One purpose of preschool programs such as Head Start is to provide children with educational skills, social skills, and health care before they begin their formal schooling. • Head Start is aimed at children around 4 years of age, especially those in lowincome and minority populations. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-65 Intelligence • Early evaluations of Head Start were not encouraging. • Efforts to influence intellectual ability cannot overcome all other environmental influences. • Despite its shortcomings, Head Start has widespread public and political support. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-66 Intelligence • Although individual differences in intelligence are due in part to heredity, the existence of group differences in IQ scores does not necessarily suggest that there are innate differences in intelligence among groups. • Critics of intelligence tests argue that we must take a closer look at the tests themselves. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-67 Intelligence • Group differences in test scores might reflect certain characteristics of the tests themselves. • Intelligence tests reflect white, middleclass values and therefore are innately biased against members of other cultural groups. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-68 Intelligence • Claude Steele of Stanford University has proposed that students’ attitudes and approach to standardized tests can also affect their performance. • The debate over differences in test scores is not merely an intellectual exercise; it has scientific, political, and social implications. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 8-69