Sumerian Art

advertisement

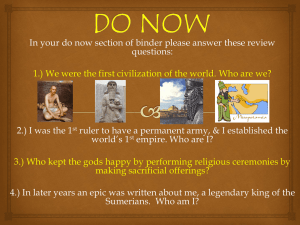

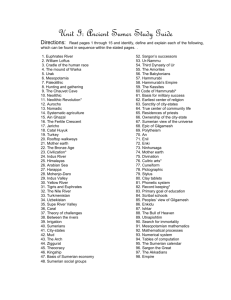

Sumerian Art Mesopotamia Paleolithic (old stone age) 2.6 million years ago to 10,000 BP from Australopithecus to Modern Man. This time period covers 99% of human technological prehistory. Mesolithic (middle stone age) 20,000 to 9,500 BP. Some overlap with the Paleolithic. Neolithic (new stone age) 10,200 to 2,000 BP Bronze age 3,300 to 1,300 BP. The beginning of metal use. Terms and Dates to know Map of Mesopotamia The art of Mesopotamia has survived in the archaeological record from early hunter-gatherer societies (10th millennium BC) on to the Bronze Age cultures of the Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian empires. These empires were later replaced in the Iron Age by the NeoAssyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires. Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Mesopotamia brought significant cultural developments, including the oldest examples of writing. The art of Mesopotamia rivalled that of Ancient Egypt as the most grand, sophisticated and elaborate in western Eurasia from the 4th millennium BC until the Persian Achaemenid Empire conquered the region in the 6th century BC. The main emphasis was on various, very durable, forms of sculpture in stone and clay; little painting has survived, but what has suggests that painting was mainly used for geometrical and plant-based decorative schemes, though most sculptures were also painted. Art of mesopotamia The art of the Sumerian civilization, as revealed by excavations at Ur, Babylon, Uruk (Erech), Mari, Kish, and Lagash, among other cities, was one of enormous power and originality that influenced all of the major cultures of ancient western Asia. Their techniques and motifs were made widely available by means of cuneiform writing, which they invented before 3000 B.C. Poor in the raw materials of art, the Sumerians traded crops from their fertile soil for the metal, stone, and wood that they required. Clay was their most abundant native material, and its qualities determined their style of baked-mud building and the nature of their fine-textured pottery. Sumerian art Sumerian art Sumerian craftsmanship was of marked excellence from very early times. A vase in alabaster from Erech (c.3500 B.C.; Iraq Mus., Baghdad) shows a detailed ceremonial procession of men and animals to the fertility goddess Inanna, carved in four bands on an elegant vase shape. A major peak of artistic achievement is represented by a female head, called Lady of Warka (Erech) from about 3200 B.C. (Iraq Mus.). It is carved in white marble with simplicity and subtlety. The vast royal cemetery at Ur has yielded many masterpieces of Sumerian work. Outstanding among these are a wooden harp detailed with gold and mosaic inlay picturing mythological scenes on the soundbox, surmounted by a black-bearded golden head of a bull (c.2650 B.C.; Univ. of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia); a gaming board of wood inlaid with bone, lapis lazuli, shell, and stone, mounted in bitumen (c.2700 B.C.; British Mus.); a ritual offering stand in the shape of a ram, made of silver, lapis lazuli, and mussel shells, rearing on his hind legs to eat from a tree of gold; and a splendid gold helmet fashioned from a single sheet of metal and beaten into the form of a head of wavy hair with a chignon at the back (c.2500 B.C.; Baghdad). Sumerian Art Warka Vase, carved stone, oldest ritual vase found in Sumer Sumerian Art Sumerian art Inanna - Female Head from Uruk, c. 3500 - 3000 B.C., Iraq Museum, Baghdad. Sumerian Art Sumerian Statuettes, from the Temple of Abu, Tel Asmar, c. 2700 - 2600 B.C., Iraq Museum, Baghdad and Oriental Institute, University of Chicago. Sumerian Art Sumerian Bull's Head, Lyre from Tomb of Paubi, c. 2600 B.C. Sumerian Art Ram (Billy Goat) and Tree, Offering Stand from Ur (to male fertility god, Tammuz), 2600 B.C. Sumerian Art Votive Statues, from the Temple of Abu, Tell Asmara c.2500 BC, limestone, shell, and gypsum Sumerian Art The Sumerian temple was a small brick house that the god was supposed to visit periodically. It was ornamented so as to recall the reed houses built by the earliest Sumerians in the valley. This house, however, was set on a brick platform, which became larger and taller as time progressed until the platform at Ur (built around 2100 BC) was 150 by 200 feet (45 by 60 meters) and 75 feet (23 meters) high. These Mesopotamian temple platforms are called ziggurats, a word derived from the Assyrian ziqquratu, meaning "high." They were symbols in themselves; the ziggurat at Ur was planted with trees to make it represent a mountain. There the god visited Earth, and the priests climbed to its top to worship. Most cities were simple in structure, the ziggurat was one of the world's first great architectural structures. Sumerian architecture Sumerian architecture White Temple and Ziggurat, Uruk (Warka), 3200 -3000 B.C. . Sumerian architecture Sumerian artifacts Sumerian artifacts Sumerian artifacts Sumerian artifacts Sumerian Artifacts Sumerian artifacts Sumerian artifacts Sumerian artifacts Sumerian artifacts Sumerian artifacts Sumerian artifacts Sumerian artifacts Sumerian rulers were to represent their people to the gods. Unlike in Egypt, the Sumerian kings were not considered divine. For this reason, the king was responsible for building and improving temples, holy places, and canals. The most famous of all Sumerian rulers was Gilgamesh of Uruk, around 2700 BC. Around his name grew up one of the first great masterpieces of poetic expression, The Epic of Gilgamesh. The Gilgamesh epic struggles with three things: 1) The power of the gods and goddesses. 2) The inevitability of death 3) The purpose of human life (Compare to the book of Job) Sumerian rulers Near the end of the epic (tablet 11), Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh the story of the flood. This story bears a striking resemblance to that of the biblical story found in Genesis. Both accounts have parallel stories of the building of boats, the coming of the torrential rain, and the sending out of birds. However, the tone is very different. The God of the Hebrews acts out of moral disapproval, while the divinities in the epic, were disturbed in their sleep by noisy mortals. Mesopotamians saw life as a continual struggle whose only alternative was the bleak darkness of death. Sumerian Rulers The epic touches on universal questions: Is all human achievement futile in the face of death? Is there a purpose to human existence? If so, how can it be discovered? Sumerian rulers