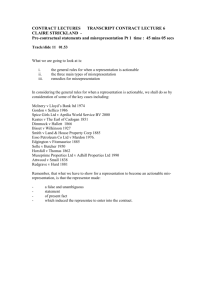

Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu

advertisement