Assessment Across A Culture of Inquiry

Assessment across

A Culture of Inquiry

Peggy Maki, Ph.D.

Education Consultant Specializing in

Assessment

Presented at Farmingdale State College

September 27, 2013 pmaki86@gmail.com

Foci

I.

A Problem-based Framework for

RFPs

II.

The Principles and Processes of

Assessing The Efficacy of Your

Educational Practices

III.

Elements of An RFP

2

What Is the Problem for First-Year

Physics Students?

3

How to restructure incorrect understanding of physics concepts became the work of physics faculty at the University of Colorado (PhET project).

That is, physics faculty became intellectually curious about how they could answer this question to improve students’ performance over the chronology of their learning.

4

A. What Research Tells Us about Learners

5

Learners Create Meaning

Egocentricity

Sociocentricity

Narrow-mindedness

Routinized habits

Meta-cognitive processes are a significant means of reinforcing learning (thinking about one’s thinking)

Learning involves creating relationships between short-term and long-term memory

6

Practice in various contexts creates deep or enduring learning

Inert learning; Activated learning

7

Transfer of new knowledge into different contexts is important to deepen understanding

Threshold Concepts

• pathways central to the mastery of a subject or discipline that change the way students view a subject or discipline, prompting students to bring together various aspects of a subject that they heretofore did not view as related (Land,

Meyer, & Smith).

8

• People learn differently and may hold onto folk or naive knowledge, incorrect concepts, misunderstandings, false information

• Deep learning occurs over time transference

9

Learning Progressions

• knowledge-based, web-like interrelated actions or behaviors or ways of thinking, transitioning, self-monitoring. May not be developed successfully in linear progression--thus necessitating formative assessment along the trajectory of learning. Movements towards increased understanding (Hess).

10

Deep Learning Occurs

When Students Are

Engaged in Their

Learning

11

Learning Strategies of Successful

Students

12

• Writing beyond what is visually presented during a lecture

• Identifying clues to help organize information during a lecture

• Evaluating notes after class

• Reorganizing notes after class

• Comparing note-taking methods with peers

• Using one’s own words while reading to make notes

• Evaluating one’s understanding while reading

• Consolidating reading and lecture notes

13

Source: Calvin Y. Yu: Director of Cook/Douglass

Learning Center, Rutgers University

How well do your students

…

Integrate Transfer Analyze

(Re)Apply Re-use Synthesize

Restructure previous incorrect learning…

14

• Within a course or module or learning experience?

• Along the chronology of their studies and educational experiences?

• From one subject or topic or focus or context to another one such as from an exercise to a case study or internship?

15

Integrated Learning….

Cognitive

Psychomotor Affective

Forms of Representation within

Contexts

16

A Problem-based Assessment Framework

17

1. Identify The Outcome or

Outcomes You Will Assess

8. Share Developments

Within and Outside The

Institution to Build

Knowledge about

Educational Practices

2. State the Research or

Study Question You Wish to Answer

7. Implement Agreed-upon

Changes and Reassess

3. Conduct a Literature

Review about That

Question

6. Collaboratively Discuss

Ways to Innovate

Pedagogy or Educational

Practices

5. Analyze and Interpret

Students ’ Work and

Students’ Responses

4. Develop a Plan to

Collect Direct and Indirect

Assessment Results that

Will Answer Your Question

II.

The Principles and Processes of

Assessing The Efficacy of Your Educational

Practices

18

• What do you expect your students to demonstrate, represent, or produce by the end of your course or educational experience, by the your program of study, or by the end of students’ undergraduate or graduate studies?

• What chronological barriers or difficulties do students encounter as they learn--from the moment they matriculate?

• How well do you identify and discuss those barrier s with students and colleagues and then track students’ abilities to overcome them so that increasingly “more” students achieve at higher levels of performance?

19

A student learning outcome statement is a complete sentence that describes what you expect students to demonstrate, represent, produce or do as a result of your teaching and learning practices. It relies on active verbs that describe what you expect students to demonstrate, and it becomes the basis of determining how you actually will assess that expectation.

20

Purposes of Student Learning Outcome Statements

Orient Students to the College’s and Each Program’s

Expectations upon Their Entry into The College or into Their

Major Program of Study (FYE?)

Enable Students to Identify Where and How They Have

Learned or Are Learning across The Institution

Position Students to Make Connections Between and

Among Their Learning Experiences along Their Educational

Journey

Lead to Collaborative Agreement about Direct and Indirect

Methods to Assess Students’ Achievement of Outcomes

Cognitive Levels of Learning: Revised

Bloom ’s Taxonomy (Handout 1)

21

Create

Evaluate

Analyze

Apply

Understand

Know

(remember)

(Lorin et. als.)

Student Learning Outcome Statements

22

Institution-level Outcomes (GE)

Program- or Department-level Outcomes (including GE)

Course Outcomes/ Service Outcomes/Educational Opportunities Outcomes

(including GE)

InstitutionLevel ( for example, FSC’s GE)

CRITICAL THINKING (REASONING)

Students will:

(1) identify, analyze, and evaluate arguments as they occur in their own or others' work; and

(2) develop well-reasoned arguments.

Department- or Programlevel (FSC’s Nursing)

Integrate evidence-based findings, research, and nursing theory in decision making in nursing practice.

23

Course- or Educational Experience-level

Integrate concepts into systems (BCS 101:

Pullan)

Analyze human agency (Reacting to the Past:

Menna)

Think critically (EGL 101 and BUS 109:

Shapiro and Singh)

24

B. Develop Curricular and Co-curricular Maps

• Help us determine coherence among our educational practices that enables us, in turn, to design appropriate assessment methods (See Handouts 2-3)

• Identify gaps in learning opportunities that may account for students ‘ achievement levels

• Provide a visual representation of students’ learning journey

25

• Help students make meaning of the journey and hold them accountable for their learning over time

26

• Help students develop their own learning map —especially if they chronologically document learning through eportfolios (See Handouts 2-

3)

C. Focus on the challenges, obstacles, or

“tough spots” that students encounter –

Research or Study Questions in Your RFPs

• Often Collaboratively developed

• Open-ended

• Coupled with learning outcome statements (Reference RFPs)

• Developed at the beginning of the assessment process

27

The Seeds of Research or

Study Questions

Informal observations around the water cooler

Results of previous assessment along the chronology of learning or at the end of students’ studies

Use of a Taxonomy of Weaknesses, Errors, or Fuzzy Thinking (see Handout 4)

28

Some Examples of

Research/Study Questions

What kinds of erroneous ideas, concepts, or misunderstandings predictably interfere with students’ abilities to learn or may account for difficulties they encounter later on?

What unsuccessful approaches do students take to solve representative disciplinary, interdisciplinary, or professional problems?

Counter that with learning about how successful students solve problems.

29

What conceptual or computational obstacles inhibit students from shifting from one form of reasoning to another form, such as from arithmetic reasoning to algebraic reasoning?

What kinds of cognitive difficulties do students experience across the curriculum as they are increasingly asked to build layers of complexity?

See Handout 5. What is your research/study question? Reference Annotated RFPs

30

D. Review your Course or Sequence of

Courses in a Program or Department for

Alignment (See Handouts 6, 7-10, 11)

31

Program outcomes

Course or experience outcomes

Criteria / standards to assess outcome

(see )

Course design: pedagogy learning context

Assignments

(see syllabus example, )

Student feedback

E. Identify or Design Assessment Methods that Provide Evidence of Product and Process

32

Direct Methods, including some that provide descriptive data about students’ meaning-making processes, such as

“Think Alouds”

Indirect Methods, including some that provide descriptive data, such as Small Group Instructional Design or salgsite.org Survey

Institutional data (course taking patterns, percentages or usage rates accompanied with observation or documentation of impact)

Some Direct Methods to Assess

Students’ Learning Processes

• Think Alouds: Pasadena City College, “How Jay

Got His Groove Back and Made Math

Meaningful” (Cho & Davis)

• Word edit bubbles

• Observations in flipped classrooms

• Students’ deconstruction of a problem or issue

(PLEs in eportfolios can reveal this - tagging, for example)

33

• Student recorder’s list of trouble spots in small group work or students’ identification of trouble spots they encountered in an assignment

• Results of conferencing with students

• Results of asking open-ended questions about how students approach a problem or address challenges

• Use of reported results from adaptive or intelligent technology

• Observations based on 360-degree classroom design (students show work as they solve problems)

34

• Use of reported results from adaptive or intelligent technology

• Focus on hearing about or seeing the processes and approaches of successful and not so successful students

• Analysis of “chunks of work” as part of an assignment because you know what will challenge or stump students in those chunks

35

Some Direct Assessment Methods to Assess Students’ Products

36

• Scenarios —such as online simulations

• Critical incidents

• Mind mapping

• Questions, problems, prompts

• Problem with solution: Any other solutions?

37

• Chronological use of case studies

• Chronological use of muddy problems

• Analysis of video

• Debates

• Data analysis or data conversion

Visual documentation: videotape, photograph, media presentation

Observation of students or other users in representative new or revised practices —what kinds of difficulties or challenges do they continue to face?

38

Assessment of the quality of X, such as proposals, based on criteria and standards of judgment

Comparison of “before” and “after” results against criteria and standards of judgment

Documentation of areas of improved or advanced ability, behavior, or results using a scoring rubric that identifies traits or characteristics at different levels of performance (Refer to Handouts 7-10)

Asking students to respond to a scenario to determine changed behavior (such as in judicial decisions or in decision making about behaviors or choices)

39

Sentence or story completion scenarios (consider

40 the validity of responses in relation to actual behavior) http://www.ryerson.ca/~mjoppe/Research

Process/841process6bl1c4bf.htm

Other for FSC?

Learning Experiences and Processes

• SALG (salgsite.org): Student Assessment of Their

Learning Gains

• Small Group Instructional Design

• Interviews with students about their learning experiences--about how those experiences did or did not foster desired learning, about the challenges they faced and continue to face.

(Refer to Handout 12 for a list of direct and indirect methods of assessment you might use to assess your students’ learning/development)

F. Chronologically Collect and Assess

Evidence of Student Learning

Baseline —at the beginning--to learn about what students know or how they reason when they enter a program

42

Formative —along the way--to ascertain students’ progress or development against agreed upon expectations.

Summative —at the end--to ascertain students’ levels of achievement against agreed upon expectations.

43

Referring to pages 34-42 or to Handout 12 ,identify both direct and indirect methods you might use to gauge evidence of the efficacy of your educational practice(s) based on baseline evidence:

Professional or legal standards/expectations for performance such as those established by the Council for the Advancement of Standards, the Association of Governing Boards, The New

Leadership Alliance for Student Learning and

Accountability , or AAC&U’s VALUE rubrics

Determine the kinds of inferences you will be able to make based on each method and the problem you are trying to solve

Identify other institutional data that might be useful when you interpret results, such as judiciary board sanctions or other records.

44

Your Method of Sampling

Ask yourself what you want to learn about your students and when you want to learn:

• All students

• Random sampling of students

• Stratified random sampling based on your demographics —informative about patterns of performance that can be addressed for specific populations, such as non-native speakers

45

Scoring

Faculty:

• Determine when work will be sampled.

• Identify who will score student work (faculty, emeritus faculty, advisory board members, others?).

• Establish time and place to norm scorers for inter-rater reliability on agreed upon scoring rubric. (See Handout 13)

46

G. Report on Results of Scoring

Evidence of Student Learning

Office of IR, Director of Assessment, or

“ designated other”:

• Analyzes and represents scoring or testing results that can be aggregated and disaggregated to represent patterns of achievement and to answer the guiding research or study question(s)

• Develops a one-page Assessment Brief

47

The Assessment Brief

Is organized around issues of interest, not the format of the data (narrative or verbal part of the brief).

Reports results using graphics and comparative formats (visual part of the brief, such as trends over time, for example, or achievement based on representative populations).

48

49

50

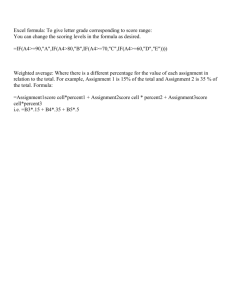

30%

20%

10%

0%

70%

60%

50%

40%

Results based on scoring students’ written work

61%

20%

11%

8%

Emerging Developing Proficient Exemplary

51

H. Establish Soft Times and Neutral Zones for Faculty and Other Professionals to

Interpret Analyzed Results or To Hear About

Your Interpretation of Results

•

Identify patterns against criteria and cohorts (if possible)

•

Tell the story that explains the results — triangulate with other reported data, such as results of student surveys .

52

Determine what you wish to change, revise, or how you want to innovate and develop a timetable to reassess once changes are implemented. (See

Handouts )

53

Collaboratively Agree on and Re-

Assess Changes

Implement agreed upon changes

Re-assess to determine efficacy of changes

Focus on collective effort —what we do and how we do it

54

III. Elements of An RFP

• State Your Outcome or Outcomes for a Time

Period (cycle of inquiry)

55

• Identify the research or study question you will try to answer within the context of current literature

• Identify two methods you will use to assess that outcome or set of outcomes

• Identify your baseline data or initial state

(where you started)

56

• Identify the criteria and standards of judgment you will use to chart progress

(professional or agreed upon performance standards, scoring rubrics)

• Identify when you will collect data

• Calendar when you will analyze and interpret results

• Identify when you will submit a report that briefly describes your interpretation of results, further needed actions, and conclusions. Tell the story that explains the results based on triangulating evidence and data you have collected

• Calendar when further actions will be taken, including plans to reassess to determine the efficacy of those further actions. (See sample plan in Handouts 14-15)

57

What if we….

Collaboratively use what we learn from this approach to assessment to design the next generation of curricula, pedagogy, instructional design, educational practices, and assignments to help increasingly more students successfully pass through trouble spots or overcome learning obstacles;

58

and, thereby, collaboratively commit to fostering students’ enduring learning in contexts other than the ones in which they initially learned.

(See Handout 16 to identify where you see the need to build your department’s or program’s assessment capacity.)

59

Works Cited

• Cho, J. and Davis, A. 2008. Pasadena City College. “How Jay Got His

Groove Back and Made Math Meaningful.” http://www.cfkeep.org/html/stitch.php?s=13143081975303&id=189465

94390037

• Hess, K. 2008. Developing and Using Learning Progressions as a

Schema for Measuring Progress. National Center for Assessment,

2008. http://www.nciea.org/publications/CCSSO2_KH08.pdf

• Land, R., Meyer, J.H.F., and Smith, J. Eds. 2010. Threshold Concepts and Transformational Learning . Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

• Lorin, A.W., Krathwohl,D.R., Airasian, P.W., and Cruikshank, K.A

. Eds.

(2000). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A

Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives : Boston,

MA.: Allyn and Bacon.

60

• Maki, P. 2010. 2nd Ed. Assessing for Learning: Building a Sustainable Commitment Across the Institution . VA:

Stylus Publishing, LLC

• National Research Council. 2002. Knowing What

Students Know: he Science and Design of Educational

Assessment . Washington, D.C.

• Yu, C. Y. “Learning Strategies Characteristic of

Successful Students.” Maki, P. 2010. p. 139.

61