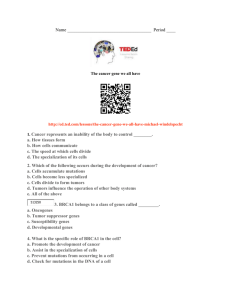

oncogene

advertisement

Cancer Tumor Cells and the Onset of Cancer Metastatic Tumor Cells Are Invasive and Can Spread Benign; Malignant; Metastasis Malignant tumors are classified as carcinomas if they derive from endoderm or ectoderm and sarcomas if they derive from mesoderm. Alterations in Cell-to-Cell Interactions Are Associated with Malignancy Tumor Growth Requires Formation of New Blood Vessels DNA from Tumor Cells Can Transform Normal Cultured Cells When DNA from a human bladder carcinoma, mouse sarcoma, or other tumor is added to a culture of 3T3 cells, about one cell in a million incorporates a particular segment of bladder carcinoma DNA that causes a distinctive phenotype. Such cells, which continue to grow when the normal cells have become quiescent, have undergone transformation and are said to be transformed. Ras protein, which participates in intracellular signal transduction pathways activated by growth factors, cycles between an inactive. Because the mutated RasD protein hydrolyzes bound GTP very slowly, it accumulates in the active state, sending a growth-promoting signal to the nucleus . Any gene, such as rasD or v-src, that encodes a protein capable of transforming cells in culture or inducing cancer in animals is referred to as an oncogene. The normal cellular gene from which it arises is called a proto-oncogene. Development of a Cancer Requires Several Mutations Epidemiology According to this "multi-hit" model, cancers arise by a process of clonal selection not unlike the selection of individual animals in a large population. A mutation in one cell would give it a slight growth advantage. Somatic Mutations in Human Tumors tumor-suppressor genes, DNA from different human colon carcinomas generally contains mutations in all these genes APC, p53, K-ras, and DCC establishing that multiple mutations in the same cell are needed for the cancer to form. Inherited Mutations That Increase Cancer Risk Overexpression of Oncogenes Overexpression of Myc protein is associated with many types of cancers, a not unexpected finding, since this transcription factor stimulates expression of many genes required for cell-cycle progression. Cancers Originate in Proliferating Cells SUMMARY Cancer is a fundamental aberration in cellular behavior, touching on many aspects of molecular cell biology. Cancer cells can multiply in the absence of growthpromoting factors required for proliferation of normal cells and are resistant to signals that normally program cell death (apoptosis). Cancer cells invade surrounding tissues. Both primary and secondary tumors require angiogenesis. Certain cultured cells transfected with tumor-cell DNA undergo transformation. Colon cancer develops through distinct morphological stages that commonly are associated with mutations in specific tumorsuppressor genes and oncogenes. Cancer cells, which are closer in their properties to stem cells than to more mature differentiated cell types, usually arise from stem cells and other proliferating cells. Proto-Oncogenes and Tumor-Suppressor Genes two broad classes of genes proto-oncogenes (e.g., ras) and tumor-suppressor genes (e.g., APC) play a key role in cancer induction. These genes encode many kinds of proteins that help control cell growth and proliferation; mutations in these genes can contribute to the development of cancer. Most cancers have inactivating mutations in one or more proteins that normally function to restrict progression through the G1 stage of the cell cycle (e.g., Rb and p16). Gain-of-Function Mutations Oncogenes into Oncogenes Convert Proto- An oncogene is any gene that encodes a protein able to transform cells in culture or to induce cancer in animals. Of the many oncogenes, all but a few are derived from normal cellular genes (i.e., protooncogenes) whose products participate in cellular growth-controlling pathways. Point mutations in a proto-oncogene gene amplification of a proto-oncogene Chromosomal translocation Oncogenes Were First Identified in CancerCausing Retroviruses The v-src gene thus was identified as an oncogene. A gene that is closely related to the RSV v-src gene, normal cellular gene, a proto-oncogene, commonly is distinguished from the viral gene by the prefix "c" (c-src). Slow-Acting Carcinogenic Retroviruses Can Activate Cellular Proto-Oncogenes Many DNA Viruses Also Contain Oncogenes Loss-of-Function Mutations in Tumor-Suppressor Genes Are Oncogenic Intracellular proteins, such as the p16 cyclin-kinase inhibitor, that regulate or inhibit progression through a specific stage of the cell cycle Receptors for secreted hormones (e.g., tumorderived growth factor b) that function to inhibit cell proliferation Checkpoint-control proteins that arrest the cell cycle Proteins that promote apoptosis Enzymes that participate in DNA repair The First Tumor-Suppressor Gene Was Identified in Patients with Inherited Retinoblastoma Loss of Heterozygosity of Tumor-Suppressor Genes Occurs by Mitotic Recombination or Chromosome Mis-segregation Proteins that promote apoptosis Enzymes that participate in DNA repair SUMMARY Dominant gain-of-function mutations in protooncogenes and recessive loss-of-function mutations in tumorsuppressor genes are oncogenic. Among the proteins encoded by proto-oncogenes are positive-acting growth factors and their receptors, signaltransduction proteins, transcription factors, and cell-cycle control proteins. An activating mutation of one of the two alleles of a proto-oncogene converts it to an oncogene. Activation of a proto-oncogene into an oncogene can occur by point mutation, gene amplification, and gene translocation. The first recognized oncogene, v-src, was identified in Rous sarcoma virus, a cancer-causing retrovirus. Retroviral oncogenes arose by transduction of cellular protooncogenes into the viral genome and subsequent mutation. The first human oncogene to be identified encodes a constitutively active form of Ras, a signal-transduction protein. Slow-acting retroviruses can cause cancer by integrating near a proto-oncogene in such a way that gene transcription is activated continuously and inappropriately. Tumor-suppressor genes encode proteins that slow or inhibit progression through the cell cycle, checkpoint-control proteins that arrest the cell cycle, receptors for secreted hormones that function to inhibit cell proliferation, proteins that promote apoptosis, and DNA repair enzymes. Inherited mutations causing retinoblastoma led to the identification of RB, the first tumor-suppressor gene. Inheritance of a single mutant allele of many tumor-suppressor genes (e.g., RB, APC, and BRCA1) increases to almost 100 percent the probability that a tumor will develop. Loss of heterozygosity of tumor-suppressor genes occurs by mitotic recombination or chromosome missegregation. Oncogenic Proliferation Mutations Affecting Cell Misexpressed Growth-Factor Genes Can Autostimulate Cell Proliferation Virus-Encoded Activators of Growth-Factor Receptors Act as Oncoproteins Activating Mutations or Overexpression of GrowthFactor Receptors Can Transform Cells Constitutively Active Signal-Transduction Proteins Are Encoded by Many Oncogenes Deletion of the PTEN Phosphatase Is a Frequent Occurrence in Human Tumors Cells lacking PTEN have elevated levels of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate and protein kinase B, which acts to prevent apoptosis. Inappropriate Expression of Nuclear Transcription Factors Can Induce Transformation SUMMARY Certain virus-encoded proteins can bind to and activate host-cell receptors for growth factors, thereby stimulating cell proliferation in the absence of normal signals. Mutations or chromosomal translocations that permit growth factor receptor protein-tyrosine kinases to dimerize lead to constitutive receptor activation in the absence of their normal ligands. Such activation ultimately induces changes in gene expression that can transform cells. Overexpression of growth factor receptors can have the same effect and lead to abnormal cell proliferation. Most tumors express constitutively active forms of one or more intracellular signal-transduction proteins, causing growthpromoting signaling in the absence of normal growth factors. A single point mutation in Ras, a key transducing protein in many signaling pathways, reduces its GTPase activity, thereby maintaining it in an activated state. The activity of Src, a cytosolic signal-transducing protein-tyrosine kinase, normally is regulated by reversible phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of a tyrosine residue near the C-terminus. The unregulated activity of Src oncoproteins that lack this tyrosine promotes abnormal proliferation of many cells. Deletion of the PTEN phosphatase promotes the PI-3 kinase pathway and activation of protein kinase B, which inhibits apoptosis. Loss of this tumor suppressor, which is common in many human cancers, reduces apoptosis. Inappropriate expression of nuclear transcription factors, such as Fos, Jun, and Myc can induce transformation. Mutations Causing Loss of Cell-Cycle Control Passage from G1 to S Phase Is Controlled by ProtoOncogenes and Tumor-Suppressor Genes Overexpression of Cyclin D1 Loss of p16 Function Loss of Rb Function Loss of TGFb Signaling Contributes to Abnormal Cell Proliferation and Malignancy SUMMARY Overexpression of the proto-oncogene encoding cyclin D1 or loss of the tumor-suppressor genes encoding p16 and Rb can cause inappropriate, unregulated passage through the restriction point in late G1, a key element in cell-cycle control. Such abnormalities are common in human tumors. TGFb induces expression of p15, leading to arrest in G1, and synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins such as collagens and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Loss of TGFb receptors or Smad 4, a characteristic of many human tumors, abolishes TGFb signaling. This promotes cell proliferation and development of malignancy.