Motivating Operations

advertisement

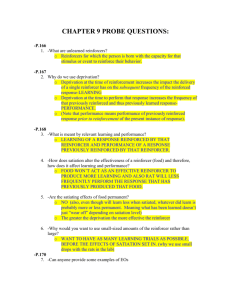

Motivating Operations Florida Tech, Spring 2005 Psych 5260, Seminar in Conceptual Issues March 2 and 3, 2005 Jack Michael, Ph.D. Psychology Department Western Michigan University jack.michael@wmich.edu phone: (269) 372-3075 fax: (269) 372-3096 Suggestions for the Student All of the information for this course is available (1) on the following slides, (2) in the accompanying lectures, and (3) in these three chapters in Michael, J., (2004). Concepts and Principles of Behavior Analysis, Revised Edition. Kalamazoo, MI: Society for the Advancement of Behavior Analysis. Chapter 1: Basic Principles of Behavior, Parts IVC10 (45-59) and IVC11 (59-64). Chapter 7: Establishing Operations, 135-150. Chapter 8: Implications and Refinements, 151-159. A detailed outline of the slides is included in your study materials, and it would be good to have it available as we go through the different topics. An Errata page is also included in your study materials. It shows errors in the first printing of Concepts and Principles, Revised Edition. You should go through C & P and write in the corrections to avoid some confusions. 2 Timetable 1955 (KU): repertoire based heavily on SHB (re motivation, Chapters 9, 10, 11) and also Wm. James lectures, and to some extent K& S (from Wike). 1957 (U of H): SHB for grad courses, K&S for an undergrad learning course (2 semesters). Thoroughly exposed to estab. oper. in Chapter 9 and 10. 1958 or 59: Holland-Skinner disks from Harvard course. Used them for some instruction. 1960 (ASU) Used H-S program in teaching Psych 112--1961 (?) until Keller took over 112 in 1964-65. Deprivation and aversive stimulation as motivational operations. 1960-1967 Gave many talks on behavior modification, rehabilitation, etc. It is not clear that I made much use of the motivation area, but probably it played a role in some highly general talks. 1967 (WMU) Taught VB (Psych 260), and statistics, JEAB, Indiv. Org. Res. Methodology (IORM), and eventually Psych 151. For 151 I used SHB, H-S, various sources. I could not determine by looking at old course materials when I started using the EO concept in the undergrad course, or in the VB course when the mand was covered. By 1980 I am pretty sure it was well developed. Critical was a grad seminar on Skinner where a group of very effective grad students and I discussed the SE (transitive CEO) at great length. I started using EO as a general term, including both deprivation and aversive stim (salt ingestion issue), and most importantly, from my perspective, with respect to learned EOs (sketch of a cat, slotted screw). Michael, J. (1982). Distinguishing between discriminative and motivational functions of stimuli. JEAB, 37, 149-155. Michael, J. (1988). Establishing operations and the mand. TAVB, 6, 3-9. Michael, J. (1993). Establishing operations. TBA, 16, 191-206. Michael, J. (2000). Implications and refinements of the EO concept. JABA, 33, 401-410. Laraway, S., Snycerski, S., Michael, J., & Poling, A. (2003). Motivating operations and terms to 3 describe them: Some further refinements. JABA, 36, 407-413. First a personal historical perspective1 UCLA, 1943, 1946-1955 B.A., M.A., Ph.D. in psychology. Main interests: Physiological psych, learning theory (Hull2, Tolman -- not much Skinner), statistics, philosophy of science. 1st academic position, 1955-57, Psych Dept at Kansas Univ. Intro psych for non majors as a teaching responsibility but not a major one: Traditional eclectic intro text; typical course format-- 3 lectures per week, exams every 5 weeks or so. My approach to lecturing: Keep a little ahead of the class in the text, supplement text with information from other sources, mainly from my own library. Studied Skinner's Science and Human Behavior to provide lecture material for the upcoming section on learning, and it was perfect for my lectures in the intro course.3 Section II is the comprehensive basic behavior analysis approach that I soon adopted and used all my life.4 4 Phase 1: Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. New York: Macmillan. Chapters 4 to 12, Section II, The Analysis of Behavior1 4. Reflexes and conditioned reflexes (respondent relations) 5. Operant behavior (rfmt, extinction conditioned rfers) 6. Shaping and maintaining operant behavior (differential rfmt, intermittent rfmt--interval, ratio) 7. Operant discrimination (discriminative stimuli--SDs, discriminative repertoires, attention) 8. The controlling environment (generalization, discrimination) 9. Deprivation and satiation (needs and drives)2 10. Emotion (as a predisposition3, responses that vary together in emotion, emotional operations) 11. Aversion, avoidance, anxiety (aversive stimuli, conditioned aversive stimuli, escape, avoidance) 12. Punishment (does it work? how? by-products, alternatives) 5 My slight modifications of the SHB arrangement 1. Unlearned environment-behavior relations 2. Respondent relations (conditioning, extinction1, S-change decrement, discrimination, and others2) [Aside on behavior-altering vs function-altering relations, considered in detail later] 3. Reinforcement: basic relation and three qualifications (RSR delay, stimulus conditions, motivating operations3) 4. Extinction4 5. Punishment: basic relation and three qualifications 6. Schedules of reinforcement 7. Motivating operations (2 defining effects, human UMOs, multiple effects, CMOs, others5) 8. Discriminative stimulus control (stimulus change decrement, SD and S∆) 9. Conditioned reinforcement and punishment 10. Escape and avoidance6 6 Phase 1: Science and Human Behavior (cont'd.) So, motivation is concerned with the operations of deprivation and satiation; and aversive stimulation. Deprivation increases and satiation decreases the probability of behavior that has been reinforced with the relevant reinforcer.1 An increase or decrease in aversive stimulation increases or decreases the probability of behavior that has terminated that type of aversive stimulation. What about the term drive?2 Skinner used it extensively in Beh. of Organisms (Chapters 9 and 10), and also in the William James Lectures (1947)3, but by SHB (1953) the chapter title was not "Drive", but rather "Deprivation and Satiation". Drive occurred frequently, but it was accompanied by much cautionary language. I avoided the term (without thinking about it), because of its internal implications. Also I was now uncomfortable with Hull's theoretical4 approach (despite my dissertation). 7 Excerpt from Skinner's 1947 William James Lectures, from page 31 of Chapter 2, "Verbal behavior as a scientific subject matter." His use of the drive concept. . . . "We may begin with the type of vb which involves the fewest variables. In any verbal community we observe that certain responses are characteristically followed by certain consequences. Wait is followed by someone's waiting, Shh by silence, and so on. . . .The case is defined by the fact that the form of the response is related to a particular consequence. There is a simple non-verbal parallel. Out! has the same ultimate effect as turning the knob and pushing against the door. The explanation of both behaviors is the same. They are examples of law-of-effect, or what I should like to call operant conditioning. Each response is acquired and continues to be maintained in strength because it is frequently followed by an appropriate consequence. The verbal response may have a slightly different "feel," but this is due to the special dynamic properties which arise from the mediation of the reinforcing organism. The basic relation is the same. The particular consequence which is used to account for the appearance of behavior of this sort - to use a technical term, the reinforcement for the response - is not the controlling variable. Reinforcement is merely the operation which establishes control. In changing the strength of such a response we manipulate any condition which alters what we call the drive. This is true whether the door is opened with a "twist and push" or with an "out!" We can make either response more likely to appear by increasing the drive to get outside - as by putting an attractive object beyond the door. We can reduce the strength of either by reducing the drive - as by introducing some object which strengthens staying in. Our control over the verbal response Out!, as in the case of any response showing a similar relations to a subsequent reinforcement, is thus reduced to our control of the underlying drive. 8 Phase 2: Keller, F. S., & Schoenfeld, W. N. (1950). Principles of psychology: Chapter 9, Motivation First read it at in 1955 or 561. K & S2 was written in 1950, but I read it after I was very familiar with Skinner's 1953 Science and Human Behavior, and made little use of it at that time. 2nd academic position, 1957-60, University of Houston. Here I used SHB and Verbal Behavior (available in 1957) for graduate seminars and informal discussion sessions.3 Also used K & S for two terms as text for an undergrad learning course. I don't remember much about my dealing with the motivation chapter; it was certainly assigned and I lectured and examined over it. I think I simply adopted the expression "establishing operation" meaning "establishes something as a reinforcer."4 9 Phase 3: Holland, J. G., & Skinner, B. F. (1961). The analysis of behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill. 1957-58, while at Houston I obtained the circular disks used at Harvard in the programmed course. Very interesting! The format1 not convenient for use in a course without the teaching machines, but the content covered the essential2 aspects of Section 2 of SHB, and programmed instruction was a very exciting new behavioral development 3rd academic position, 1960-67, Arizona State University Taught undergrad statistics, several grad courses, and by 1962 I was teaching an intro course for majors, using the HollandSkinner programmed textbook3 (and my own lab manual4). Fred Keller started teaching that intro course using his PSI5 approach in late 64-early 65, and using K&S as his text, but I made little or no use of the book once the H-S program came out. 10 Phase 4: Motivation in decline Although quite important to Skinner (1938, 1953) and to Keller and Schoenfeld (1950),1 motivation during the 60s and 70s was hardly mentioned as a significant behavioral concept. Deprivation was mentioned but played only a small role. Why? (1) Knowledge of intermittent rfmt schedules2 showed that behavior is much more sensitive to rfmt frequency and rfmt schedule than to deprivation. (2) Wants, needs, drives, etc. were usually explanatory fictions referring to inner entities inferred from the behavior they were supposed to explain. (3) Also with increasing applied work, generalized conditioned rfmt (praise, points, money) was usually the immediate consequence for much human behavior, which made deprivation and aversive stimulation less necessary3. But ultimately motivational variables could not be ignored 11 without leaving the system incomplete. 4th (and last) academic position: 1967-2003, WMU Taught undergrad VB course (called "Social Psych"), statistics, JEAB, Indiv. Org. Res. Methodology, and eventually (~1970) an intro course for majors, for which I used SHB, H-S, and various sources. For my teaching I had to have consistent, coherent, concepts and principles1. So deprivation/satiation and aversive stimulation must be dealt with, even though such effects seem less important than reinforcement frequency. Deprivation increases and satiation decreases the frequency2 of behavior that has been reinforced with the relevant reinforcer. An increase or decrease in aversive stimulation increases or decreases the (current) frequency of behavior that has terminated that type of aversive stimulation. 12 Phase 5: Necessity for a general concept But this was somewhat unsatisfactory. (1) There are a few operations with similar effects but which are neither deprivation or aversive stim. (salt ingestion, blood loss, perspiration; temperature too high/low)?1 (2) Also, I needed a technical term for this area that would refer to deprivation, aversive stimulation, and any other variables that have similar effects. Motivation is too broad in its ordinary usage (including reinforcement). Drive lends itself too easily to an internal interpretation. The solution: Sometime during the early or mid 70s it occurred to me that what these operations did was establish something as a reinforcer. Let's call them establishing operations.2a, 2b An unanticipated result of this usage was to emphasize the reinforcer-establishing (later "value-altering") effect as separate from the evocative (later "behavior-altering" effect 13 much more than with K & S (1950) or SHB (1953).3 Learned motivation:1 The sketch of a cat Skinner's example of how to get someone to mand a pencil was the initial stimulus for the learned EO analysis. The sketch of a cat: In Verbal Behavior (p. 253) Skinner explained how one could use basic verbal relations to get a person to say pencil. To evoke a mand of that form, "we could make sure that no pencil or writing instrument is available, then hand our subject a pad of paper appropriate to pencil sketching, and offer him a handsome reward for a recognizable picture of a cat."2 How should we classify the offer of money for the sketch in its evocation of the response pencil?3 An SD? Why not? The main purpose of the 1982 paper was to provide an analysis of what I first called an establishing stimulus (SE), and later a transitive conditioned establishing operation (CEO-T).4 Michael, J. (1982). Distinguishing between discriminative5 and 14 motivational functions of stimuli. JEAB, 37, 149-155. 1982-1993: EO terminology was adopted to some extent in the applied field from the 1982 paper.1 So, a new paper: Michael, J. (1993) Establishing operations. TBA, 16, 191-206. (somewhat clearer language, more details re pain as an EO, two new learned EOs2) McGill, P.(1999). Establishing operations: Implications for the assessment, treatment, and prevention of problem behavior. JABA, 32, 393-418.2 Michael, J. (2000). Implications and refinements of the EO concept. JABA, 33, 401-410. Iwata, B. A., Smith, R. G., & Michael, J. (2000). Current research on the influence of EOs on behavior in applied settings. JABA, 33, 411-428. Laraway, S., Snycerski, S., Michael, J., & Poling, A. (2003). Motivating operations and terms to describe them: Some further refinements. JABA, 36, 407-413. 15 QuickTime™ and a TIFF (LZW) decompressor are needed to see this picture. 16 This ends the historical introduction to the topic, which consisted of 14 slides. Now back to a logical and conceptual rather than a historical development of motivation. 17 Motivating Operations1 I. Definition and Characteristics next A. Basic features B. Important details II. Distinguishing Motivative from Discriminative Relations III. Unconditioned Motivating Operations A. UMOs vs CMOs B. Nine main UMOs for humans C. Weakening the effects of UMOs D. UMOs for punishment E. A complication: Multiple effects IV. Conditioned Motivating Operations A. Surrogate CMO (CMO-S) B. Reflexive CMO (CMO-R) C. Transitive CMO (CMO-T) V. General Implications of MOs for Behavior Analysis 18 I. Definition and Characteristics A. Basic features Brief history a. Skinner, 1938 & 1953 b. K & S, 1950 c. Michael's extension Figure 1. EO defining effects named, with food and pain examples Figure 2. MO defining effects Figure 3. EO and MO effects compared B. Important details 1. What about punishment? 2. Direct & Indirect Effects. 3. Not Just Frequency. 4. Misunderstandings. 5. Current vs. Future Effects a. Evocative/Abative vs. Function-Altering b. Antecedent vs. Consequence 19 A. Basic features: Brief history a. Skinner, 1938 & 1953: Motivation concerned with deprivation/satiation and aversive stimulation. Deprivation/satiation alter the probability of behavior that has been reinforced with the relevant reinforcer. Alteration in aversive stimulation alters the probability of behavior that has reduced such aversive stimulation. But unsatisfactory: a general term needed for both (drive no good). Also salt ingestion, blood loss, etc. b. Keller & Schoenfeld, 1950. Both deprivation and aversive stimulation are operations that establish a drive. Food deprivation, for example, establishes food as a reinforcer. Aversive stimulation establishes its reduction as a reinforcer. Establishing operation is thus a good general term--implies the environment rather than an internal state. 20 A. Basic features: Brief history (cont'd.) c. Michael, 1982. Let us use establishing operation (EO) for any environmental variable (deprivation, aversive stimulation, salt ingestion, becoming too warm or too cold, and also a learned variable) that does these two things: i. Increases the current reinforcing effectiveness of some stimulus, object, or event. ii. Increases the current frequency of (evokes) all behavior that has obtained that stimulus, object, or event in the past. Furthermore let us give each of these effects a name: 21 Fig. 1 Establishing Operations (EOs): 2 Defining Effects Rfer Establishing or Abolishing Effect EOs establish the current reinforcing effectiveness of some stimulus, object, or event. (And establish includes the effect in the opposite direction, abolish.) Evocative or Abative Effect EOs evoke any behavior that has been reinforced by the same stimulus that is altered in rfing effectiveness by the same EO. (And evoke includes an effect in the opposite direction, abate.) Food deprivation increases and food ingestion decreases the reinforcing effectiveness of food. current frequency of any behavior that has been reinforced1 by food. An increase in pain causes an increase, and a decrease in pain causes a decrease in the reinforcing effectiveness of pain reduction. current frequency of any behavior that has been rfed by pain reduction. 22 Fig. 2 Motivating Operations (MOs): 2 Defining Effects Value-Altering Effect MOs alter the current reinforcing effectiveness of some stimulus, object, event. Reinforcer Establishing Abolishing Effect Effect Behavior-Altering Effect MOs alter any behavior that has been reinforced by the same stimulus, object, or event that is altered in value by the same MO. Evocative Effect Abative Effect Food deprivation increases and food ingestion decreases the reinforcing effectiveness of food. current frequency of any behavior that has been rfed by food. An increase in pain causes an increase, and a decrease in pain causes a decrease in the reinforcing effectiveness of pain reduction. current frequency of any behavior that has been rfed by pain reduction. 23 Figure 3: EO and MO comparison Establishing Operations (EOs): 2 Defining Effects Rfer Establishing or Abolishing Effect EOs establish the current reinforcing effectiveness of some stimulus, object, or event. (And establish includes the effect in the opposite direction, abolish.) Evocative or Abative Effect EOs evoke any behavior that has been reinforced by the same stimulus that is altered in rfing effectiveness by the same EO. (And evoke includes an effect in the opposite direction, abate.) Motivating Operations (MOs): 2 Defining Effects Value-Altering Effect MOs alter the current reinforcing effectiveness of some stimulus, object, event. Reinforcer Establishing Abolishing Effect Effect Behavior-Altering Effect MOs alter any behavior that has been reinforced by the same stimulus, object, or event that is altered in value by the same MO. Evocative Effect Abative Effect 24 Motivating Operations Where are we? I. Definition and Characteristics A. Basic features next B. Important details II. Distinguishing Motivative from Discriminative Relations III. Unconditioned Motivating Operations A. UMOs vs CMOs B. Nine main UMOs for humans C. Weakening the effects of UMOs D. UMOs for punishment E. A complication: Multiple effects IV. Conditioned Motivating Operations A. Surrogate CMO (CMO-S) B. Reflexive CMO (CMO-R) C. Transitive CMO (CMO-T) V. General Implications of MOs for Behavior Analysis 25 IB. Important details 1. What about MOs and punishment? 2. Direct and Indirect Effects. 3. Not Just Frequency. 4. Common Misunderstandings. 5. Current vs. Future Effects; Evocative/Abative vs. Function-Altering Effects; Antecedent vs. Consequence Effects 6. Generality depends on MO as well as stimulus conditions 26 IB. Important Details 1. What about MOs and punishment? Only recently considered–most of MO theory and knowledge relates to MOs for rfmt. Some in a later section. 2. Direct and indirect effects1 a. MO alters response frequency directly. b. MO alters evocative strength of relevant SDs. c. Also establishing/abolishing effects, and evocative and abative effects re relevant conditioned reinforcers (but not for the same response) 3. Not just frequency: magnitude (more or less forceful R), latency (shorter or longer time from MO or SD to R), relative frequency (response occurrences per response opportunities), & others. 27 IB. More Details1 4. Misunderstanding #1: Evocative/abative effect is secondary to the value-altering effect. This is the interpretation of altered response frequency as solely the result of contact with the reinforcer of altered effectiveness, i.e. follows that contact and behavior is increased or decreased because of the smaller or greater strengthening effect of the reinforcer on subsequent responses. But not true. Evocative/abative effects can be seen in extinction responding--that is, without contacting the reinforcer. Best thought of as Two Separate Effects. 28 IB. More Details (cont'd.) But the two effects do often work together. Reinforcing effectiveness will only be seen in the future, after some behavior has been reinforced, but this can be immediately after the MO alteration. Thus ongoing increased reinforcer effectiveness will combine with an evocative effect. If behavior is occurring too infrequently: Strengthening the MO will result in responses being followed by more effective rfer (rfer estab. effect); and all behavior that has been so rfed will be occurring at a higher frequency (evocative effect). The increase cannot be unambiguously interpreted, but in practice it may make no difference. If behavior is occurring too frequently: Weakening MO will result in a weaker evocative effect, and a weaker reinforcer. 29 IB. More Details (still cont'd.) 4. Misunderstanding #2: The cognitive interpretation This is belief that evocative and abative effects only work because the individual understands (is able to verbally describe) the situation and behaves appropriately as a result of understanding. Not true. Reinforcement automatically adds the reinforced behavior to the repertoire that will be evoked or abated by the relevant MO. The individual does not have to understand anything in the sense of verbal description. (*Consider rats.) There are 2 harmful effects of this belief. Little effort may made to alter the behavior of non-verbal persons who seem incapable of such understanding. Teachers are not prepared for disruptive behavior acquired by non-verbal persons who have been so reinforced. 30 IB. More Details (finished at last) 5. Current vs Future Effects; Evocative/Abative vs Function-Altering Effects; Antecedents vs Consequents Evocative/abative (antecedent) variables with current effects: Operant repertoire: (MO + SD)----->R relations Respondent repertoire: US or CS----->UR or CR Function-altering variables (consequences) with future effects: Operant consequences: R followed by SR, SP, Sr, Sp; and R occurs w/o consequence (extinction) (Respondent pairing/unpairing: CS paired w/ US; CS occurs w/o US (extinction) 6. Generality depends on MO as well as stim conditions 31 1st. Review: Basic features, important details. IA. Basic Features. Brief history (Skinner, K & S, Michael) EO defining effects with examples MO defining effects with examples EO and MO effects compared IB. Important details. 1. What about punishment? 2. Direct and indirect effects 3. Not just frequency 4. Two misunderstandings 5. Current vs future; evocative/abative vs function-altering; antecedents vs consequents 6. Generality depends on MO as well as stim conditions 32 Motivating Operations Where are we? I. Definition and Characteristics A. Basic features B. Important details II. Distinguishing Motivative from Discriminative Relations III. Unconditioned Motivating Operations A. UMOs vs CMOs B. Nine main UMOs for humans C. Weakening the effects of UMOs D. UMOs for punishment E. A complication: Multiple effects IV. Conditioned Motivating Operations A. Surrogate CMO (CMO-S) B. Reflexive CMO (CMO-R) C. Transitive CMO (CMO-T) V. General Implications of MOs for Behavior Analysis next 33 II. A Critical Distinction: Motivative vs. Discriminative Relations; MO vs. SD A. The General Contrast Both MOs and SDs are learned, operant, antecedent, evocative/abative, not function-altering relations. SDs evoke (S∆s abate) because of differential past availability of a reinforcer. MOs evoke or abate because of the differential current effectiveness of a reinforcer But more is needed on differential availability. 34 B. Differential Availability Refined An SD (discriminative stimulus) is a type of stimulus that evokes a type of response. But so does the respondent CS (conditioned stimulus). An SD is a type of S that evokes a type of R because that R has been reinforced in that S. But it will not have strong control unless it occurs without rfmt. in the absence of the S (in the S∆ condition).1 An SD evokes its R because it has been reinforced in the SD and has occurred w/o rfmt. in S∆. But now another assumption must be made explicit. 35 C. MO in S∆ condition An SD evokes its R because it has been reinforced in the SD and has occurred w/o rfmt. in S∆. But, occurring w/o rfmt in S∆ would be behaviorally irrelevant unless the unavailable reinforcement would have been effective as reinforcement if it been obtained. This means that the relevant MO for the rfmt in SD must also be in effect during S∆.1 In everyday* language: For development of an SD---R relation, an organism must have wanted something in the SD, R occurred, and it was reinforced; and also must have wanted it in the S∆, R occurred, and was not reinforced. (*I'll admit that this is not exactly everyday language.) 36 D. Food example: Could food deprivation (or relevant internal stimuli1) qualify as an SD, and absence of deprivation as an S∆, for a food reinforced response? Two SD requirements: (1) R must have been rfed with food in SD and (2) occurred w/o food rfmt in S∆, and the relevant MO (food deprivation) must have been in effect during S∆. (1) Food deprivation sort of 2 meets the requirement: Food available and R rfed w/ food in the presence of deprivation. (2) R may have occurred w/o food rfmt in S∆, but S∆ is specified as the absence of food deprivation (or of related internal stimuli), so MO is clearly absent. Doesn't qualify! The absence of food deprivation does not qualify as an S∆ but food deprivation clearly qualifies as an MO. Everyday language: (1) Food may have been wanted in the SD condition, and obtained. (2) But what was wanted in the S∆ 37 condition that was not obtained? Nothing. E. Pain example: Could pain qualify as SD, and pain absence as S∆, for an R rfed by pain reduction? Two SD requirements: (1) R was rfed with pain reduction in SD (painful S present) and (2) occurred w/o pain reduction rfmt. in S∆ (when painful S was absent), and the relevant MO (painful S) must have been in effect during S∆. (1) Pain sort of meets the first requirement.1 Pain reduction may have been available and may have typically followed R in the presence of pain. (2) R may have occurred w/o being followed by pain reduction in S∆ (when pain was not present), but the relevant MO (painful S) was specified as not present. Pain absence clearly fails to qualify as an S∆, so pain no good as SD. Pain does not qualify as an SD, but clearly qualifies as an MO. Everyday language: (1) Pain reduction was wanted in SD and obtained. (2) What was wanted in S∆ condition.2 Nothing. 38 2nd. Review II. Motivative vs. discriminative relations: MO vs. SD A. The general contrast. B. Differential availability refined. C. Another assumption: MO in S∆. D. Example: Food deprivation as SD? Why not? E. Example: Pain as SD? Why not? 39 Motivating Operations Where are we? I. Definition and characteristics A. Basic features B. Important details II. Distinguishing motivative from discriminative relations III. Unconditioned Motivating Operations next A. UMOs vs. CMOs B. Nine main UMOs for humans C. Weakening the effects of UMOs D. UMOs for punishment E. A complication: Multiple effects IV. Conditioned Motivating Operations A. Surrogate CMO (CMO-S) B. Reflexive CMO (CMO-R) C. Transitive CMO (CMO-T) V. General Implications of MOs for Behavior Analysis 40 IIIA. UMOs vs. CMOs UMOs are events, operations, or stimulus conditions with unlearned value-altering effects. Conditioned motivating operations (CMOs) are MOs with learned value-altering effects. The distinction depends solely on the value-altering effect; an MO's behavior-altering (evocative/abative) effect is always learned. UMO: Humans are born with the capacity to be reinforced by food when food deprived (reinforcer-establishing effect), but the behavior that gets food has to be learned. CMO: The capacity to be reinforced by having a key, when we have to open a locked door (reinforcer-establishing effect) depends on our history with doors and keys. And we also have to learn behavior that obtains keys (evocative effect). 41 IIIB. Nine main human UMOs1 1. Five deprivation and satiation UMOs: food, water, sleep, activity, and oxygen2. 2. UMOs related to sex. 3. Two UMOs related to uncomfortable temperatures: being too cold or too warm. 4. A UMO consisting of painful stimulation increase.3 42 IIIB1. Five Deprivation/Satiation UMOs: food, water, sleep, activity, and oxygen. Reinforcer establishing effect: X deprivation increases the effectiveness of X as a reinforcer. Evocative effect: X deprivation increases the current frequency of all behavior that has been reinforced with X. Reinforcer abolishing effect: X consumption decreases the effectiveness of X as a reinforcer. Abative effect: X consumption decreases the current frequency of all behavior that has been reinforced with X. 43 IIIB2a. UMOs related to sex For many mammals, time passage and environmental conditions related to successful reproduction (e.g. ambient light conditions, average daily temperature) produce hormonal changes in the female that as UMOs cause contact with a male to be an effective reinforcer for the female. These changes produce visual changes in some aspect of the female's body and elicit chemical attractants that function as UMOs making contact with a female a rfer for the male and evoking behavior that has produced such contact. These changes may also evoke behaviors by the female (a sexually receptive posture) that function as UMOs for sexual behavior by the male. There is also often a deprivation effect that may also function as a UMO for both genders. 44 IIIB2b. The sex UMO in humans In the human, learning plays such a strong role in the determination of sexual behavior that the role of unlearned environment-behavior relations has been difficult to determine. The effect of hormonal changes in the female on the female's behavior is unclear; and similarly for the role of chemical attractants in changing the male's behavior. Other things being equal, both male and female seem to be affected by the passage of time since last sexual activity (deprivation) functioning as a UMO with establishing and evocative effects, and sexual orgasm functioning as a UMO with abolishing and abative effects. In addition, tactile stimulation of erogenous regions of the body seems to function as a UMO making further similar stimulation even more effective as rfmt and evoking any behavior that has achieved such further stimulation. 45 IIIB3a. Temperature UMOs, Too Cold Becoming too cold, reinforcer establishing effect: Increases effectiveness of an increase in temperature as a reinforcer. Evocative effect: Increases the current frequency of all behavior that has increased warmth. Return to normal temperature1, reinforcer abolishing effect: Decreases2 effectiveness of becoming warmer as a reinforcer. Abative effect: Decreases2 current frequency of all behavior that has increased warmth. 46 IIIB3b. Temperature UMOs, Too Warm Becoming too warm, reinforcer establishing effect: Increases effectiveness of a decrease in temperature as a reinforcer. Evocative effect: Increases the current frequency of all behavior that has decreased warmth. Return to normal temperature1, reinforcer abolishing effect: Decreases effectiveness of becoming cooler as a reinforcer. Abative effect: Decreases current frequency of all behavior that has decreased warmth. 47 IIIB4a. Painful Stimulation UMO Reinforcer Establishing Effect: An increase in pain increases the current reinforcing effectiveness of pain reduction.1 Evocative Effect: An increase in pain increases current frequency of all types of behavior that have been reinforced by pain reduction.1 Reinforcer Abolishing Effect: A decrease in pain decreases the current reinforcing effectiveness of pain reduction. Abative Effect: A decrease in pain decreases the current frequency of all types of behavior that have been reinforced with pain reduction. The pain MO is an appropriate conceptual model for motivation by any form of worsening.2 48 IIIB4b. More on pain as a UMO Skinner’s emotional predisposition refers to an operant1 aspect of emotion, as a form of MO.2 For anger, the cause is any worsening in the presence of another organism—pain, interference with rfed behavior, etc. For some organisms, this seems to function as a UMO making signs of damage or discomfort3 by the other organism function as rfmt, and evoking behavior that has been so rfed. Whether such effects are related to UMOs in humans is presently unclear. The similarity of emotional and motivational functional relations was well developed by Skinner in his 1938 book, The Behavior of Organisms. The concept of an emotional predisposition (and a more extensive analysis of emotion) is in Science and Human Behavior, 1953, pp. 162--170. 49 IIIB. Practice Exercise #1: UMO Effects Provide each of the following: 1. Evocative effect of sleep deprivation. 2. Reinforcer-abolishing effect of water ingestion. 3. Abative effect of pain decrease. (Be careful.) 4. Reinforcer-establishing effect of becoming too cold. 5. Abative effect of pain increase. (trick question) 6. Rfer-abolishing effect of engaging in much activity. 7. Evocative effect of sex deprivation. 8. Rfer-abolishing effect of a return to normal temperature after having been too warm. (What has been rfing?) 9. Evocative effect of pain increase. (Be careful.) 10. Rfer-establishing effect of pain increase. (Be careful.) 50 IIIB. Answers for Exercise #1: UMO Effects 1. Increased current frequency of all behavior that has facilitated going to sleep. 2. Decreased reinforcing effectiveness of water. 3. Decreased current frequency of all behavior that has been rfed by pain decrease (not "by pain"). 4. Increased reinforcing effectiveness of temperature increase. 5. Pain increase does not have an abative effect. 6. Decreased reinforcing effectiveness of activity. 7. Increased current frequency of all behavior that has led to sexual stimulation. 8. Decreased reinforcing effectiveness of becoming cooler. 9. Increased current freq of all behavior that has reduced pain. 10. Increased reinforcing effectiveness of pain reduction. 51 Motivating Operations Where are we now? I. Definition and characteristics A. Basic features B. Important details II. Distinguishing motivative from discriminative relations III. Unconditioned Motivating Operations A. UMOs vs. CMOs B. Nine main UMOs for humans C. Weakening the effects of UMOs next D. UMOs for punishment E. A complication: Multiple effects IV. Conditioned Motivating Operations A. Surrogate CMO (CMO-S) B. Reflexive CMO (CMO-R) C. Transitive CMO (CMO-T) V. General Implications of MOs for Behavior Analysis 52 IIIC. Weakening the Effects of UMOs For practical reasons it may be necessary to weaken some UMO effects. Permanent weakening of UMO's unlearned rferestablishing effect is not possible. Pain increase will always make pain reduction more effective as rfmt. Temporary weakening by rfer-abolishing and abative variables is possible. Food stealing can be temporarily abated by inducing food ingestion, but when deprivation recurs, the behavior will come back. Evocative effects depend on a history of rfmt, and can be reversed by extinction procedure–let the evoked R occur without rfmt (not possible in practice if control of rfer is not possible), and abative effects of punishment history can be reversed by recovery from pmt procedure–R occurs without the punishment. 53 IIID. UMOs for Punishment An environmental variable that (1) alters the punishing effectiveness (up or down) of a stimulus, object, or event, and (2) alters the current frequency (up or down) of all behavior that has been so punished is an MO for punishment; and if the first effect does not depend on a learning history, then it is a UMO. 1. Reinforcer-establishing effects UMOs: Pain increase/decrease will always increase/decrease the effectiveness of pain reduction as a rfer. Also true for other uncond. pners (some sounds, odors, tastes, etc). MOs for conditioned punishers. Most punishers for humans are conditioned, not unconditioned punishers. Two kinds: a. S paired with an unconditioned pner (SP), then the UMO is the UMO for that unconditioned pner. b. Historical relation to reduced availability of rfers, then UMO is the UMO for those rfers. (cont'd on next slide) 54 1. Reinforcer-establishing effects (cont'd.) Examples: Removing food as pmt (or changing to an S related to less food) will only punish if food is a reinforcer, so the MO for food removal as pmt is food deprivation.1 Social disapproval as a punisher (frown, head shake, "bad!") may work because of being paired with SP like painful stimulation, so MO would be the MO for the relevant SP. More often social disapproval works because some of the rfers provided by the disapprover have been withheld when disapproval stimuli have occurred. MO would be the MOs for those reinforcers. Time-out as punishment is similar. The MOs are the MOs for reinforcers that have been unavailable during time-out. Response cost (taking away tokens, money, or reducing the score in a point bank) only works if the things that can be obtained with the tokens, etc. are effective as reinforcers at the time response cost procedure occurs. (continued on next slide) 55 2. Abative effects of MO for pmt: Quite complex. An increase in an MO for pmt would abate (decrease the current frequency of) all behavior that had been punished with that type of punisher. To observe this effect, however, the punished behavior must be occurring so that a decrease can be observed. This depends on the current strength of the MO for the reinforcers for the punished behavior. This means that the observation of an MO abative effect for punishment requires the MO evocative effect of the rfmt for the behavior that was punished, otherwise there would be no behavior to punish. Example for time-out punishment: Assume a time-out procedure was used to punish behavior that was disruptive to a therapy situation. Problems: Only if MOs for the rfers available in the situation had been in effect would the time-out have functioned as punishment. Then, only if those MOs were in effect would one expect to see the abative effect of the previous punishment procedure on the disruptive behavior. But only if the MO for the disruptive behavior were in effect would there be any disruptive behavior to be abated. These issues have not been much considered in behavior analysis up to now. But you should be aware of the complications. They will be there. 56 3rd. Review C. Weakening the effects of UMOs. 1. Weakening reinforcer establishing effects. Permanent (not possible). Temporary (evocative weakening). 2. Weakening evocative effects. D. MOs for punishment. Definition. 1. Rfer establishing effects. Pain and other UMOs. MOs for conditioned reinforcers. Examples (social disapproval, time out, response cost). 2. Abative effects (considerable complexity). 57 Motivating Operations Where are we now? I. Definition and characteristics A. Basic features B. Important details II. Distinguishing motivative from discriminative relations III. Unconditioned Motivating Operations A. UMOs vs. CMOs B. Nine main UMOs for humans C. Weakening the effects of UMOs D. UMOs for punishment next E. A complication: Multiple effects IV. Conditioned Motivating Operations A. Surrogate CMO (CMO-S) B. Reflexive CMO (CMO-R) C. Transitive CMO (CMO-T) V. General Implications of MOs for Behavior Analysis 58 E. Multiple effects: Many environmental events have more than one behavioral effect. 1. SD and Sr in a simple operant chain 2. MO evocative/abative effects vs SR/SP function-altering effects 3. Practical implications 4. Terminological note: Aversive stimuli 59 1. SD and Sr in a simple operant chain Food-deprived pigeon presses a treadle (R1) protruding from the chamber wall, which turns on an auditory tone stimulus. With the tone on, the pigeon pecks a disk on the wall (R2), which delivers 3 sec exposure to a grain hopper where the pigeon can eat the grain. tone off rfmt off R1 tone ON rfmt off R2 tone ON rfmt ON 3 sec R1 = treadle press, R2 = key peck, rfmt = 3" grain available Tone onset is SD for key peck, and Sr for treadle push. 60 pecking key Pigeon Operant Chamber key lights aperture light food aperture key lights grain hopper down treadle food aperture Rfmt = aperture light on, grain hopper up to the bottom of the food aperture. (Pigeon sticks its head into the aperture and pecks at the grain.) After 3 sec, light goes off and hopper goes back down (where grain can't 61 be reached). pecking key Pigeon Operant Chamber key lights aperture light food aperture key lights grain hopper up treadle food aperture Rfmt = aperture light on, grain hopper up to the bottom of the food aperture. (Pigeon sticks its head into the aperture and pecks at the grain.) After 3 sec, light goes off and hopper goes back down (where grain can't be reached). 62 pecking key Pigeon Operant Chamber key lights aperture light food aperture key lights grain hopper down treadle food aperture Rfmt = aperture light on, grain hopper up to the bottom of the food aperture. (Pigeon sticks its head into the aperture and pecks at the grain.) After 3 sec, light goes off and hopper goes back down (where grain can't 63 be reached). 1. SD and Sr in a simple operant chain a) Evocative/abative (antecedent) variables with current effects: I. Operant repertoire: (MO + SD)----->R relations II. Respondent repertoire: CS----->CR b) Function-altering (consequence) variables with future effects: I. Operant consequences: R followed by SR, SP, Sr, Sp; R occurs without consequence II. (Respondent pairing/unpairing: CS paired w/ US; CS without US) (Above is from the earlier section IB5, slide 31.) 64 2. MO evocative/abative & SR/SP function-altering effects. Pain increase has an MO evocative effect (increase in the current frequency of (evokes) all behavior reinforced by pain reduction). Pain increase also functions as SP to cause a decrease in the future frequency of the particular type of behavior that immediately preceded that instance of pain increase. Food ingestion has an MO abative effect (decrease in the current frequency of (abates) all food rfed behavior). Food ingestion also functions as SR to cause an increase in the future frequency of the particular type of behavior that immediately preceded that instance of food ingestion, operant conditioning. 65 2. MO evocative/abative & SR/SP function-altering effects: Direction of the effects Becoming too cold or too warm is similar to pain increase in producing increases in current frequency and decreases in future frequency. However the evocative effects of most of the deprivation MOs are too slow acting to function as effective consequences. Abative effects are all quick acting and the relevant variables will also function as reinforcers. Note that SD and Sr effects are in the same direction–both are increases (not the same behavior). MO and related SR/SP effects are typically in opposite directions, thus the MO decreased the current frequency of all food rfed behavior (abated it); the SR caused an increase in future frequency (but not in the same behaviors). 66 3. Practice Exercise For each of the following, name the effect (evocative, abative, reinforcer, punisher) and describe it using the language of the preceding slide. I will give the first two. 1. The function-altering effect of pain decrease. (Answer: Reinforcer: Increases the future frequency of what ever behavior preceded that instance of pain reduction.) 2. The MO effect of returning to a comfortable temperature after having been too warm. (Answer: Abative: Decrease in all the behavior that has caused a decrease in temperature.) 3. MO effect of becoming too cold. 4. Function-altering effect of becoming too cold. 5. MO effect of water ingestion. 6. Function-altering effect of being able to sleep after sleep deprivation. (More on the next slide.) 67 3. More Practice 7. MO effect of sexual orgasm. 8. Function-altering effect of suddenly not being able to breathe. 9. Function-altering effect of return to a comfortable temperature after having been too cold. 10. Function altering effect of sexual orgasm. 11. MO effect of pain decrease. 12. MO effect of activity deprivation. 13. Function-altering effect of engaging in activity after activity deprivation. 14. MO effect of becoming too cold. 15. MO effect of oxygen deprivation. 68 4. Practical Implications. Many behavioral interventions are chosen because of their MO evocative or abative effects, or because of their reinforcement or punishment effects. Any of these operations will have related operations in the opposite direction. These effects could be counter-productive and should be understood and prepared for. MO weakening = reinforcement: MO weakened to decrease some undesirable behavior, (weaker SR for ongoing behavior and weaker evocative effect): food satiation to reduce food stealing, attention satiation to reduce disruptive behavior relevant to attention as a reinforcer. But some behavior will be reinforced by the satiation operation. Maybe not a problem, but could be. (continued on next slide) 69 4. Practical Implications (cont'd.) MO strengthening = punishment: MO strengthened to increase some desirable behavior (stronger SR for ongoing behavior plus stronger evocative effect): food deprivation to enhance effectiveness of food as reinforcer; attention deprivation, music deprivation, toy deprivation, etc. to increase effectiveness of those items as reinforcers. But, some behavior will be punished by the operation unless deprivation onset is very slow. And even with slow build-up deprivation effects, if they have been systematically related to a stimulus condition, then the presentation of that stimulus condition will function as punishment. 70 4. Practical Implications (cont'd.) c) Reinforcement = MO weakening: Food, attention, toys, etc. used a reinforcers to develop new behavior. But providing these reinforcers will weaken the MO, thus ongoing rfers will be less effective and evocative effect will be weakened. If reinforcers are small the effect may not be counter productive, as with pigeons on 24-hour food deprivation being reinforced with 3 seconds exposure to grain. However it is not clear what "small" means in terms of the kinds of reinforcers mentioned above. 71 4. Practical Implications (cont'd.) d) Punishment = MO strengthening: Considering that most punishers used deliberately to weaken human behavior are stimulus conditions that have been related to a lower availability of various kinds of reinforcement, such a punishment operation will be like deprivation. It will result in a stronger Sr for ongoing behavior plus a stronger current frequency (stronger evocation). With a time-out procedure, the reinforcing effects of obtaining a reinforcer will be greater when one is obtained (perhaps by stealing) and the behavior that has gotten such reinforcers will be stronger. 72 5. Terminological Note: Aversive and appetitive stimuli. Some environmental events have all three of the following effects: a) MO evocative effects. b) Punishment function-altering effects. c) Certain respondent evocative effects: heart rate increase, adrenal secretion, peripheral vasodilation, galvanic skin response, and so on, often called the activation syndrome). (Continued on the next slide.) 73 5. Aversive and appetitive stimuli (cont'd.) Such events are often referred to as aversive stimuli, where the specific behavioral function [MO, SP or Sp, and US (unconditioned stimulus)] is not specified. This type of omnibus term is of problematic value. In many cases it seems to be little more than a technical translation of mentalisms like "an unpleasant stimulus", or "I don't like it." It can be avoided in favor of the more specific terms (MO, SP or Sp or US) if possible. Appetitive stimuli has sometimes been used for events with (a) MO abative effects,(b) reinforcing function-altering effects, and (c) respondent evocative effects characteristic of happiness, affection etc. But like aversive stimulus it is too unspecific, and happily is not much used in behavior analysis. 74 4th. Review E. Multiple effects 1. SD and S∆ in a simple operant chain evocative/abative effects function-altering effects 2. MO evocative/abative effects & SR/SP functionaltering effects. 3. Practice exercises 4. Practical implications a. MO weakening = reinforcement b. MO strengthening = punishment c. Reinforcement = MO weakening d. Punishment = MO strengthening 5. Terminological Note: Aversive stimuli 75 Motivating Operations Where are we now? I. Definition and characteristics A. Basic features B. Important details II. Distinguishing motivative from discriminative relations III. Unconditioned Motivating Operations A. UMOs vs. CMOs B. Nine main UMOs for humans C. Weakening the effects of UMOs D. UMOs for punishment E. A complication: Multiple effects IV. Conditioned Motivating Operations (Review of the UMO-CMO distinction) A. Surrogate CMO (CMO-S) B. Reflexive CMO (CMO-R) C. Transitive CMO (CMO-T) V. General Implications of MOs for Behavior Analysis next 76 Unconditioned vs. Conditioned MOs UMOs are events, operations, or stimulus conditions with unlearned reinforcer-establishing effects. Conditioned motivating operations (CMOs) are MOs with learned reinforcer-motivating effects. The distinction depends solely upon reinforcer-establishing effect; an MO's evocative/abative effect is always learned. Humans are born with the capacity to be reinforced by food when food deprived (reinforcer-estab. effect), but the behavior that gets food has to be learned. The capacity to be reinforced by having a key, when we have to open a locked door (reinforcer-estab. effect) depends on our history with doors and keys. And we also have to learn how to obtain the key (evocative effect). (Same as slide 41.) 77 IV. Conditioned Motivating Operations: Three kinds. Variables that alter the reinforcing effectiveness (value) of other stimuli, objects, and events but only as a result of a learning history can be called Conditioned Motivating Operations, CMOs. There seem to be three kinds of CMOs: A. Surrogate: CMO-S B. Reflexive: CMO-R C. Transitive: CMO-T 78 IVA. Surrogate CMO (CMO-S) 1. Description a. Pairing: The pairing of stimuli develops the respondent CS, and the operant Sr, and Sp, and possibly the SD. Maybe also an MO, by pairing with another MO. Such a CMO will be called a surrogate CMO, a CMO-S. It would have the same reinforcer-establishing effect and the same evocative effect as that of the MO it had been paired with. Example: A stimulus paired with the UMO of being too cold might 1) increase the effectiveness of warmth as a reinforcer, and 2) evoke behavior that had been so reinforced more than needed for the actual temperature. b. Evidence for such a CMO is not strong. Also it would not have good survival value, still evolution does not always work perfectly. 79 IVA1. CMO-S (cont'd.) c. Emotional MOs: With sexual motivation, MOs for aggressive behavior, and the other emotional MOs, the issue has not been addressed in terms specific to the CMO, because its distinction from CS, Sr, and Sp has not been previously emphasized. The surrogate CMO is only just beginning to be considered within applied behavior analysis (see McGill, 1999, p.396), but its effects could be quite prevalent. d. Practical importance: From a practical perspective, it may be helpful to consider the possibility of this type of CMO when trying to understand the origin of some puzzling or especially irrational behavior. 2. Weakening the effects of the CMO-S: Any relation developed by pairing can be weakened by the two forms of unpairing1. The stimulus that had been paired with being too cold would weaken if it occurred repeatedly in normal temperature, or if one was too cold as often in the absence as in the presence of 80 the stimulus. Motivating Operations Where are we now? I. Definition and characteristics A. Basic features B. Important details II. Distinguishing motivative from discriminative relations III. Unconditioned Motivating Operations A. UMOs vs. CMOs B. Nine main UMOs for humans C. Weakening the effects of UMOs D. UMOs for punishment E. A complication: Multiple effects IV. Conditioned Motivating Operations (Review of the UMO-CMO distinction) A. Surrogate CMO (CMO-S) next B. Reflexive CMO (CMO-R) C. Transitive CMO (CMO-T) 81 V. General Implications of MOs for Behavior Analysis IVB. Reflexive CMO 1. Description a) b) c) d) e) Escape and avoidance Escape extinction Avoidance: CMO-R defined Avoidance extinction Avoidance misconceptions 2. Human Examples: a) Ordinary social interactions b) Academic demand situation 82 IVB1. CMO-R Description: a. Escape-Avoidance The warning stimulus in an avoidance procedure. Animal lab escape-avoidance as a box diagram. tone off shock off 30" R1 tone on shock off tone on shock on 5" R2 R1 = lever press, the avoidance rsp. R2 = chain pull, the escape rsp. Escape: What evokes R2? The shock onset. What is rfer for R2? Shock termination. How should the evocative relation be named? Is shock onset an SD for R2? No, because S∆ condition is defective–no MO for rfmt consisting of shock termination when shock is not on. (What is wanted? Nothing.) Shock is a UMO (recall earlier section on MO vs. SD, and pain as UMO. 83 IVB1. CMO-R b. Escape Extinction Animal lab escape-avoidance procedure as a diagram. tone off shock off 30" R1 tone on shock off tone on shock on 5" R2 R1 = lever press, the avoidance rsp. R2 = chain pull, the escape rsp. How can R2 be reduced or prevented? What would extinction of R2 consist of? Extinction = R occurs w/o SR. Remove R2 contingency (shown dimmed) from the diagram–not an actual lab procedure. In general, to extinguish escape behavior the rsp must not escape the later worsening. How else to prevent R2? Omit shock, but this is only 84 temporary–evocative, not function-altering. IVB1. CMO-R c. Avoidance & Definition tone off shock off 30" R1 tone on shock off tone on shock on 5" R2 R1 = lever press, the avoidance rsp. R2 = chain pull, the escape rsp. What evokes R1? Onset of the warning stimulus (tone). What reinforces R1? Avoiding the shock? No, terminating the tone. How should the evocative relation be named? Is tone onset an SD for R1? No, because the S∆ condition is defective–no MO for rfmt consisting of tone termination when tone is not on. (What is wanted? Nothing.) Tone is a CMO-R. (Why not a UMO?) CMO-R: Any stimulus that has systematically preceded the 85 onset of any avoidable worsening. IVB1. CMO-R d. Avoidance Extinction tone off shock off 30" R1 tone on shock off R1 = lever press, the avoidance rsp. 5" tone on shock on R2 R2 = chain pull, the escape rsp. How can R1 be weakened or prevented? Evocative weakening: Leave tone off. But only temporary. When tone next comes on R will occur. Function-altering weakening: True Extinction: R1: Remove R1 contingency (dimmed out). R1 occurs, tone stays on and shock occurs when it would have if R1 had not occurred. Result: Reduction in R frequency will take place at a usual rate for extinction. 86 IVB1. CMO-R e. Avoidance Misconceptions tone off shock off 30" R1 tone on shock off 5" omitting shock R1 = lever press, the avoidance rsp. Widespread misconceptions about avoidance: 1st. Misconception: Rfmt for R1 is not getting the shock. Wrong: Too long-range and a nonevent. Rfmt for R is termination of the warning S. 2nd. Misconception: To extinguish R1, when R fails to occur omit shock and return to the beginning. Wrong: Leave warning S on when R occurs and give shock when it is due. This error is based on the previous one. Omitting shock will lead to reduction of R1 frequency, but should not be called 87 extinction. This procedure is shown on the next slide. IVB1. CMO-R e. Misconceptions (cont'd.) tone off shock off 30" R1 tone on shock off 5" omitting shock R1 = lever press, the avoidance rsp. Widespread misconceptions about avoidance: 3rd. Misconception: Avoidance behavior extinguishes very slowly. Based on erroneous definition of extinction; also on the notion that organism has to find out that the shock is gone and the avoidance R prevents this discovery; also on research results where the shock was omitted, and the behavior decreased very slowly. Why does this work? Tone-off is better than tone-on, but only because shock is closer once tone comes on. When shock is omitted tone-on loses is aversiveness, so (tone-on--->tone-off) loses its reinforcing value–but only very gradually. 88 IVB2. CMO-R Human examples a. Everyday social interactions. The CMO-R is important in identifying a negative aspect of many everyday interactions that might seem free of deliberate aversiveness. The interactions are usually interpreted as a sequence of SD--->R interactions, with each one being an opportunity for one person to provide some form of rfmt to the other person. But there is a slightly darker side to everyday life. i. Response to a request for information: You are on campus and stranger asks you where the library is. The appropriate R is give the information or say that you don't know. What evokes your answer? The request. What reinforces your response? The person asking will smile and thank you. Also you will be rfed by the knowledge that you have helped another person. 89 IVB2. CMO-R Human examples a. Everyday social interactions (cont'd.) So the request is an SD. But, it also begins a brief period that can be considered a warning stimulus, and if a rsp is not made soon, some form of mild social worsening will occur. The asker may repeat the question, more clearly or loudly, and will think you are strange if you do not respond. You, yourself, would consider your behavior socially inappropriate if you did not respond quickly. Even with no clear threat implied for non-responding, our social history implies some form of worsening for continued inappropriate behavior. So, the request plus the brief following period is in part a CMO-R in evoking the response. It is best considered a mixture of positive and negative parts. But when the question is an inconvenience (e.g. when you are in a rush to get somewhere) the CMO-R is probably the main component. 90 IVB2. Human examples a. Everyday social interactions (cont'd.) ii."Thanks" When a person does something for another that is a kindness of some sort, it is customary for the recipient of the kindness to thank the person performing the kindness, who then typically says "You're welcome." What evokes the thanking rsp, and what is its rfmt? Clearly it is evoked by the person's performing the kindness. And the "You're welcome" acknowledgment is the obvious rfmt. So the kindness is an SD in the presence of which a "Thanks" response can receive a "You're welcome." But what if the recipient fails to thank the donor? The performance of the kindness is also a CMO-R that begins a period that functions like a warning stimulus. Failure to thank is inappropriate. 91 IVB2. CMO-R Human examples b. Academic Demand. In applied behavior analysis the CMO-R may be an unrecognized component of procedures used for training individuals with defective social repertoires. Learners are typically asked questions or given verbal instructions, and appropriate responses are rfed in some way (an edible, praise, a toy, etc.). Should the questions and instructions be considered primarily SDs evoking behavior because of the availability of the rfers? I think not. What happens if an appropriate response does not occur fairly quickly? Usually a more intense social interaction ensues. The question usually has relatively strong CMO-R characteristics. Although it may not be possible to completely eliminate this negative component, it is important to recognize its existence and to understand its nature and origin. 92 IVB3. CMO-R Weakening the CMO-R Evocative and temporary weakening will occur if the warning stimulus does not occur. Function-altering weakening will result from extinction (R does not terminate the warning stimulus) and from unpairing (ultimate worsening does not occur even if the warning stimulus is not terminated, or occurs even when the warning stimulus is terminated). The analysis of weakening the CMO-R involved in everyday social interactions becomes more complex than seems appropriate for this type of presentation. It is possibly useful to suggest that the larger the CMO-R vs. the SD component, the "meaner" the culture. Early phases of an academic demand situation may evoke tantrums, self-injury, aggressive behavior, etc. This behavior may have been rfed by terminating the early phases and not progressing to the more demanding phases. 93 IVB3. CMO-R Weakening the CMO-R (cont'd.) The effects of the CMO-R in evoking the problem behavior can be weakened by extinction or by unpairing. If later phases must occur because of the importance of the repertoire being taught, and assuming they cannot be made less aversive, then extinction of problem behavior is the only practical solution. (Unpairing will lead to no training.) But the demand can often be made less aversive. Better instruction will result in less failure and more frequent positive rfmt. The CMO-R will weaken as the final components become less demanding. The negativity of the training situation would not be expected to vanish completely unless the rfers in the nontraining situation did not compete with what was available in the training situation. However, as the SD component related to the positive reinforcers in the situation becomes more important as compared with the CMO-R component, problem behavior should be less frequent and less intense. 94 5th. Review Review of the UMO - CMO difference. A. Surrogate CMO a) Description in terms of pairing b) Example B. Reflexive CMO 1. Avoidance and escape a) Animal lab procedure b) Evocation and rfmt of the escape and the avoidance Rs c) Extinction of escape and of avoidance Rs d) Misconceptions (rfmt, true extinction vs. unpairing) 2. Human examples a) Everyday social interactions b) Academic demand 3. Weakening the effects of the CMO-R (everyday social 95 interactions, academic demand) Motivating Operations Where are we now? I. Definition and characteristics A. Basic features B. Important details II. Distinguishing motivative from discriminative relations III. Unconditioned Motivating Operations A. UMOs vs. CMOs B. Nine main UMOs for humans C. Weakening the effects of UMOs D. UMOs for punishment E. A complication: Multiple effects IV. Conditioned Motivating Operations (Review of the UMO-CMO distinction) A. Surrogate CMO (CMO-S) B. Reflexive CMO (CMO-R) C. Transitive CMO (CMO-T) V. General Implications of MOs for Behavior Analysis next 96 IVC. Transitive CMO, CMO-T 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Definition and animal examples. Human CMO-T Examples Weakening the Effects of the CMO-T Importance for Language Training Practical implications of CMO-T in general 97 CMO-T: 1. Definition & animal example CMO-T: An environmental variable related to the relation between another stimulus and some form of rfmt, and thus establishes the reinforcing effectiveness of the other stimulus, evokes all behavior that has produced that stimulus. Examples: UMOs function as CMO-Ts for stimuli that are Srs because of their relation to the relevant SR. tone off rfmt off R1 tone ON rfmt off R2 tone ON rfmt ON 3 sec R1 = treadle press, R2 = key peck, rfmt = 3" grain available Food deprivation is CMO-T for rfer effectiveness of tone, and evokes all Rs that have produced tone (in this case, R1). 98 CMO-T: 1. Another animal example tone off rfmt off R1 tone ON rfmt off R2 tone ON rfmt ON 3 sec R1 = treadle press, R2 = key peck, rfmt = 3" grain available Onset of tone makes sight of the key effective as rfmt and evokes observing behavior–visual search behavior. Why is tone onset not an SD for looking for the key? What is the rfmt for looking for key? Seeing key. Is the tone onset related to the availability of this rfmt? Can the key be more easily seen when tone is on than when tone is off? No. Tone makes seeing key more valuable, not more available. As a suppose SD for looking for key, tone is defective in two ways. (1) An SD is a stimulus in the absence of which the relevant rfer is not available, but the key can be successfully looked for when tone is off. (2) When tone is off, there is no MO making 99 sight of key valuable. CMO-T: 1. Avoidance and All 3 CMOs tone off shock off 30" R1 tone on shock off tone on shock on 5" R2 R1 = lever press, the avoidance rsp. R2 = chain pull, the escape rsp. 1. Tone onset is CMO-S in evoking chain pull. 2. Tone onset is CMO-R in evoking lever press. 3. Tone onset is CMO-T in evoking looking for the lever. CMO-T: 2. A complication: SDs may also be involved. Although tone onset is not an SD but rather a CMO-T for looking for the key, it is an SD for pecking the key. What is the rfmt for pecking the key? Food. Is food rfmt more available when tone is on 100 than when it is not on? Yes. 3. Human CMO-T: a. Flashlight example The rfing effectiveness of many human Srs is dependent on other stimulus conditions because of a learning history. Thus conditioned rfing effectiveness depends on a context. When the context is not appropriate the S may be available, but not accessed because it is not effective rfmt in that context. A change to an appropriate context will evoke behavior that has been followed by that S. The occurrence of the behavior is not related to the availability of the S, but to its value. Flashlights are available in most home settings, but are not accessed until existent lighting becomes inadequate, as with a power failure. Sudden darkness, as a CMO-T, evokes getting a flashlight. The motivative nature of this relation is not widely appreciated. The sudden darkness is usually interpreted as an SD for looking for a flashlight. But are flashlights more available in the dark? No. They are more valuable. 101 3. Human CMO-T: b. Slotted screw example Consider a workman disassembling a piece of equipment, with an assistant providing tools as they are requested. The workman sees a slotted screw and requests a screwdriver. The sight of the screw evoked the request, the rfmt for which is receiving the tool. Prior to the CMO-T analysis the sight of the screw would have been considered an SD for requesting the tool. But the sight of such screws have not been differentially related to the availability of screwdrivers. Workmen's assistants have typically provided requested tools irrespective of the stimulus conditions that evoked the request. The sight of the screw does not make screwdrivers more available, but rather more valuable--a CMO-T, not an SD. SDs are involved: The screw is an SD for unscrewing motions; and the request is also dependent upon the presence of the 102 assistant as an SD. But it is a CMO-T for the request. 3. Human CMO-T: The danger stimulus A security guard hears a suspicious sound. He activates his mobile phone which signals another guard, who calls back and asks if help is needed (the Sr for the first guard's response). Is the suspicious sound an SD for contacting the other guard? Only if the rfmt for the rsp is more available in the presence than in the absence of the suspicious sound, which it is not. The sound makes the rsp by the other guard more valuable, not more available, so it is a CMO-T for activating the phone. The CMO-T is not an SD because the absence of the stimulus does not qualify as an S∆. The relevant rfmt is just as available in the supposed S∆ as in the SD; and there is no MO for the rfmt in the S∆ condition--nothing is wanted. The other guard's phone ringing is an SD for his activating his phone and saying "Hello," getting some rsp from a person phoning has not been available from non-sounding phones. (A danger signal is not a CMO-R, because it is rfed by producing 103 another S, not its own removal.) CMO-T: 4. Weakening the CMO-T Abative weakening: The CMO-T can be temporarily weakened by weakening the MO related to the ultimate outcome of the sequence of behaviors. If the workman is told that the equipment does not have to be disassembled for this job the behavior evoked by the sight of the slotted screw will be weak. Of course the next time a screw has to be removed the request will be as strong as before. Function-altering weakening by extinction: Something changes so that requests are no longer honored, e.g. assistants now believe that workmen should get their own tools. By one type of unpairing, if screwdrivers no longer work. Construction practices changed so that screws are welded as soon as they are inserted. By another type of unpairing, if slotted screws can be unscrewed just as easily by hand as with the screwdriver. 104 IVC. 5. The CMO-T and language training It is increasingly recognized that mand training is an important part of language programs for individuals with nonfunctional verbal repertoires. With such individuals, manding seldom arises spontaneously from tact and receptive language training. The learner has to want something, make an appropriate request, and receive what was requested, and thus the rsp comes under control by the MO and becomes a part of the individual's verbal repertoire as a mand. The occurrence of UMOs can be taken advantage of to teach mands, but there are two problems. Manipulating UMOs will usually raise ethical problems. Much of the human mand repertoire is for conditioned rather than unconditioned reinforcers. The CMO-T can be a way to make a learner want anything that 105 can be a means to another end. 5. The CMO-T and language training (cont'd.) Any stimulus, object or event can be the basis for a mand simply by arranging an environment in which that stimulus can function as an Sr. Thus if a pencil mark on a piece of paper is required for an opportunity to play with a favored toy, mands for a pencil and a piece of paper can be taught. This approach is somewhat similar to Hart and Risley's (1975) procedure called incidental teaching. It is also an essential aspect of the verbal behavior approach to much current work in the area of autism, for example by Sundberg, M. L., & Partington, J. W. (1998). Teaching language to children with autism or other developmental disabilities. Pleasant Hill, CA : Behavior Analysts, Inc. 106 6. Practical implications of the CMO-T vs. SD analysis. A CMO-T evokes behavior because of its relation to the value of a consequence; an SD evokes behavior because of its relation to the availability of a consequence. This distinction must be relevant in subtle ways to the effective understanding and manipulation of behavioral variables for a variety of practical purposes. To develop new behavior or to eliminate old behavior by manipulating the value when availability is relevant, or availability when value is relevant will be inadequate or at least less effective than the more precise manipulation. The distinction is an example of a terminological refinement, not an empirical issue. Its value will be seen in the improved theoretical and practical effectiveness of those whose verbal behavior has been affected. 107 6th. Review C. Transitive CMO 1. Definition and animal examples 2. A complication: SDs are also involved 3. Human CMO-T examples a) Flashlight b) Slotted screw c) Danger stimulus 4. Weakening the effects of the CMO-T 5. Importance for language training 6. Practical implications of the CMO-T vs. SD analysis. 108 V. General Implications for Applied Behavior Analysis. Behavior analysis makes extensive use of the three-term contingency relation involving stimulus, response, and consequence. However, the reinforcing or punishing effectiveness of the consequence in developing control by the stimulus depends on an MO. And the future effectiveness of the stimulus in evoking the response depends on the presence of the same MO in that future condition. In other words, the three-term relation cannot be fully understood, nor most effectively used for practical purposes without a thorough understanding of motivating operations. In principle it should be referred to as a four-term contingency. 109 The slide show has ended. 110 111