Downloadable Word Doc for Rhetorical Analysis

advertisement

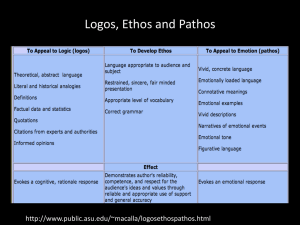

TEXT / VISUAL ANALYSIS Part 1 of 4: Reading Between the Text 1. Identify the SOAPS. o Speaker refers to the first and last name of the writer and any credentials that lend to his or her authority on the matter at hand. Note that if the narrator is different from the writer, though, it could also refer to the narrator. o Occasion mostly refers to the type of text and the context under which the text was written. For instance, there is a big difference between an essay written for a scholarly conference and a letter written to an associate in the field. o Audience is for whom the text was written. This relates to occasion, since the occasion can include details about the audience. In the example above, the audience would be a conference of scholars versus an associate in the field. o P The purpose refers to what the writer wants to accomplish in the text. It usually includes selling a product or point of view. o S The subject is simply the topic the writer discusses in the text. 2. Examine the appeals. Appeals are the first classification of rhetorical strategy. o Ethos (ethical appeal) relies on the writer's credibility and character. Mentions of a writer's character or qualifications usually qualify as ethos. Example: in analyzing an article on improving familiar relations, one may note that the writer is a family therapist with 20 years of practice o Logos (logical appeal) uses reason to make an argument. Most academic discourse should make heavy use of logos. Logos is the use of evidence, data, and undeniable facts as support. o Pathos (pathetic appeal) seeks to evoke emotion. These emotions can include anything from sympathy and anger to the desire for love. If an article about violent crime provides personal, human details about victims of violent crime, the writer is likely using pathos. 3. Note style details. Style details are the second rhetorical strategy. o Analogies and figurative language, including metaphors and similes, demonstrate an idea through comparison. o Repetition of a certain point or idea is used to make that point seem more memorable. o Imagery often affects pathos. The image of a starving child in a third-world country can be a powerful way of evoking compassion or anger. o Diction refers to word choice. Emotionally-charged words have greater impact, and rhythmic word patterns can establish a theme more effectively. o Tone means mood or attitude. A sarcastic essay if vastly different from a scientific one. o Addressing the opposition demonstrates that the writer is not afraid of the opposing viewpoint. It also allows the writer to strengthen his or her own argument by cutting down the opposing one. 4. Form an analysis. Before beginning the writing of an analysis, determine what the information gathered suggests. o Identify how the rhetorical strategies of appeals and style help the author achieve his or her purpose. Determine if any of these strategies fail and hurt the author instead of helping. o Speculate on why the author may have chosen those rhetorical strategies for that audience and that occasion. Determine if the choice of strategies may have differed for a different audience or occasions. Part 2 of 4: Writing the Introduction 1. Identify the purpose. In some way, let the reader know that the paper is a rhetorical analysis. o By letting the reader know that the paper is a rhetorical analysis, he or she knows exactly what to expect. If one does not let the reader know this information beforehand, he or she may expect to read an evaluative argument instead. o Do not simply state, "This paper is a rhetorical analysis." Weave the information into the introduction as naturally as possible. 2. State the text being analyzed. Clearly identify the text or document being analyzed. o The introduction is a good place to give a quick summary of the document. Keep it quick, though. Save the majority of the details for the body paragraphs, since most of the details will be used in defending the analysis. 3. Briefly mention the SOAPS. Mention the speaker, occasion, audience, purpose, and subject of the text. o These details do not necessarily need to mention this order. Include the details in a matter that makes sense and flows naturally within the introductory paragraph. 4. Specify a thesis statement. The thesis statement is the key to a successful introduction and provides a sense of focus for the rest of the essay. There are several ways to state the intentions for the essay. o Try stating which rhetorical techniques the writer uses in order to move people toward his or her desired purpose. Analyze how well these techniques accomplish this goal. o Consider narrowing the focus of the essay. Choose one or two design aspects that are complex enough to spend an entire essay analyzing. o Think about making an original argument. If the analysis leads to a certain argument about the text, focus the thesis around that argument and provide support for it throughout the body of the paper. Part 3 of 4: Writing the Body 1. Organize the body paragraphs by rhetorical appeals. The most standard way to organize body paragraphs is to do so by separating them into sections that identify the logos, ethos, and pathos. o The order of logos, ethos, and pathos is not necessary set in stone. If the intention is to focus on one more than the other two, briefly cover the two lesser appeals in the first two sections before elaborating on the third in greater detail toward the middle and end of the paper. o For logos, identify at least one major claim and evaluate the document's use of objective evidence. o For ethos, analyze how the writer or speaker uses his or her status as an "expert" to enhance credibility. o For pathos, analyze any details that alter the way that the viewer or reader may feel about the subject at hand. Also analyze any imagery used to appeal to aesthetic senses, and determine how effective these elements are. o Wrap things up by discussing the consequences and overall impact of these three appeals. 2. Write the analysis in chronological order, instead. This method is just about as common as organizing the paper by rhetorical appeal, and it is actually more straight-forward. o Start from the beginning of the document and work through to the end. Present details about the document and the analysis of those details in the order the original document presents them. o The writer of the original document likely organized the information carefully and purposefully. By addressing the document in this order, the analysis is more likely to make coherent sense by the end of the paper. 3. Provide plenty of evidence and support. Rely on hard evidence rather than opinion or emotion for analysis. o Evidence often includes a great deal of direct quotation and paraphrasing. o Point to spots in which the author mentioned his or her credentials to explain ethos. Identify emotional images or words with strong emotional connotations as ways of supporting claims to pathos. Mention specific data and facts used in analysis involving logos. 4. Maintain an objective tone. A rhetorical analysis can make an argument, but it needs to be scholarly and reasonable in the analysis of the document. o Avoid use of the first-person words "I" and "we." Stick to the more objective third-person. Part 4 of 4: Writing the Conclusion 1. Restate the thesis. Do not simply repeat the thesis from the introduction word-for-word. Instead, rephrase it using new terminology while essentially sharing the same information. o When restating the thesis, quickly analyze how the original author's purpose comes together. 2. Restate the main ideas. In restating the main ideas, explain why they are important and how they support the thesis. o Keep this information brief. These restatements of the main ideas should only serve as summaries of the support. 3. Specify if further research is needed. If more information needs to be gathered to further the analysis, say so. o Indicate what that research must entail and how it would help. o Also state why the subject matter is important enough to continue researching and how it has significance to the real world. Tips for writing 1. Avoid the use of "In conclusion..." While many writers may be taught to end conclusion paragraphs with this phrase as they first learn to write essays; however, one should never include this phrase in an essay written at a higher academic level. This phrase and the information that usually follows it is empty information that only serves to clutter up the final paragraph. 2. Do not introduce any new information in the conclusion. Simply summarize the important details of the essay.