Stanford v. Roche webinar slides 7-7

advertisement

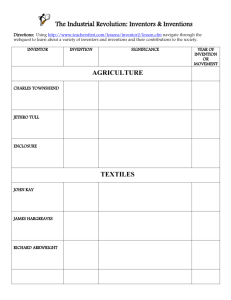

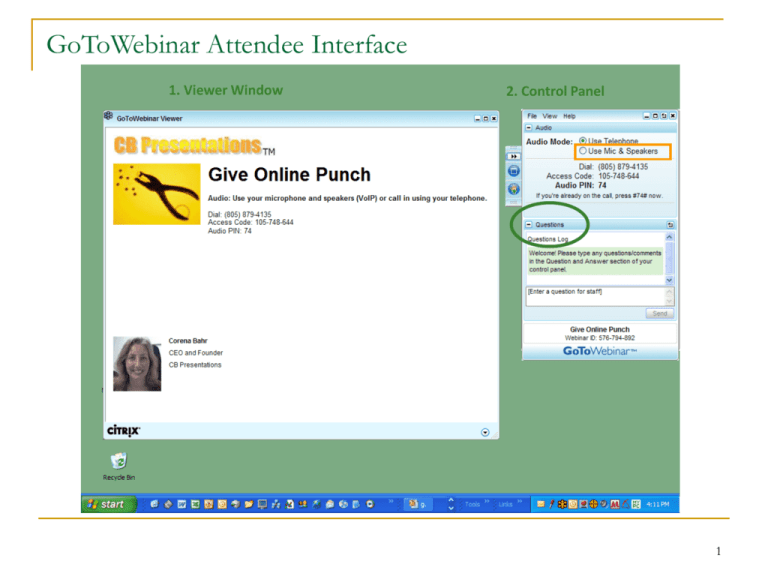

GoToWebinar Attendee Interface 1. Viewer Window 2. Control Panel 1 Thanks to our Sponsors!! 2 STANFORD V. ROCHE 3 Factual background In 1985, Cetus, then a small California research company, began to develop methods for quantifying levels of HIV in human blood samples utilizing polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In 1988, Cetus began to collaborate with scientists at Stanford’s Department of Infectious Diseases to test the efficacy of new AIDS drugs. Dr. Mark Holodniy joined Stanford as a research fellow in the department around that time. At that time, he signed a Copyright and Patent Agreement (CPA) stating that he “agree[d] to assign” to Stanford his “right, title and interest in” inventions resulting from his employment at the University. Slip op. at 1-2. 4 Factual Background At Stanford, Dr. Holodniy undertook to develop an improved method for quantifying HIV levels in patient blood samples using PCR. Because Dr. Holodniy was largely unfamiliar with PCR, his supervisor arranged for him to conduct research at Cetus. As a condition of gaining access to Cetus, Dr. Holodniy signed a Visitor’s Confidentiality Agreement (VCA). That agreement stated that Dr. Holodniy “will assign and do[es] hereby assign” to Cetus his “right, title and interest in each of the ideas, inventions and improvements” made “as a consequence of [his] access” to Cetus. Id. at 2. 5 Dr. Holodniy’s Assignments Stanford CPA (June 1988) “I agree to assign or confirm in writing to Stanford … that right, title, and interest in and to … such inventions as required by Contracts or Grants,” defined to include “agreements … with third parties including the United States Federal Government” Under Arachnid (CAFC), this language creates a future interest, not a present assignment Cetus VCA (Feb. 1989) “I will assign and hereby do assign to CETUS my right, title, and interest” in inventions conceived “as a consequence of my access to CETUS’ facilities or information” Under FilmTec (CAFC), this creates a present assignment Stanford Assignment (1995) Present assignment recorded in PTO 6 Factual background For the next nine months, Dr. Holodniy conducted research at Cetus on a part-time basis. Dr. Holodniy and others devised a PCR-based procedure for calculating the amount of HIV in a patient’s blood. Over the next few years, Stanford obtained written assignments of rights from the Stanford employees involved in devising the procedure, including Dr. Holodniy, and filed several patent applications related to the procedure. Beginning in 1999, Stanford secured the three patents-in-suit covering the HIV measurement process. Id. 7 Factual background In 1991, Roche Molecular Systems, a company that specializes in diagnostic blood screening, acquired Cetus’s PCR-related assets, including all rights Cetus had obtained through agreements like the VCA signed by Dr. Holodniy. After conducting clinical trials on the HIV quantification method, Roche commercialized the procedure in 1995. Id. at 2-3. 8 Procedural background In 2005, Stanford filed suit against Roche, alleging that certain Roche HIV test kits infringed three U.S. patents relating to quantifying HIV in human blood samples and correlating the measurements to the effectiveness of antiretroviral drugs. Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior Univ. v. Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., 583 F.3d 832, 836 (Fed. Cir. 2009). Among other defenses, Roche challenged the validity of the patents and asserted that it was a co-owner based on the assignment from Dr. Holodniy. On one summary judgment motion, the district court rejected Roche’s co-ownership defense, finding that the Bayh-Dole Act voided the assignment from Dr. Holodniy to Cetus. On a later summary judgment motion, the district court determined that all three patents were invalid as obvious. Id. at 838-39. 9 Procedural background On appeal, the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s ruling on Roche’s co-ownership defense. Id. at 836-37 and 848. The court found that Roche was a co-owner based on the assignment from Dr. Holodniy and therefore remanded the case with instructions to dismiss it because Stanford lacked standing. Id. 10 Statutory background (per Stanford) Prior to the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act in 1980, there were two systems that governed who acquired title to Government-funded inventions. The first system involved “vesting” statutes and regulations that vested title in the Government and “divested” inventors of all of their interests. The second system involved the use of Institutional Patent Agreements (“IPA”s), some of which provided licenses to the Government and ownership interests to inventors, while others provided title to the Government. 11 Statutory background (per Stanford) The Bayh-Dole Act was designed to create a uniform system of addressing ownership interests in an “invention of the contractor” under a federallyfunded contract. Section 202(c) of the Act provides a number of actions that a federal contractor must take if it wants to acquire title to a subject invention. Section 202(a) of the Act states that a contractor “may elect to retain title to any subject invention,” provided that it has complied with the requirements of Section 202(c). 12 Statutory Language “Each nonprofit organization or small business firm may … elect to retain title to any subject invention….” § 202(a). “The term ‘subject invention’ means any invention of the contractor conceived or first actually reduced to practice in the performance of work under a funding agreement….” § 201(e). QUESTION: Does this language, in conjunction with the requirements of §202(c), automatically vest perfect title to federally-funded inventions in the federal contractor? 13 Petition for Certiorari Question Presented: “Whether a federal contractor university’s statutory right under the Bayh-Dole Act, 35 USC 200-212, in inventions arising from federally-funded research can be terminated unilaterally by an individual inventor through a separate agreement purporting to assign the inventor’s rights to a third party.” 14 Supreme Court’s decision The U.S. Supreme Court decided that the Bayh-Dole Act did not automatically vest title to inventions in federal contractors; rather, the Court found title to the invention at issue vested initially in the inventor in accordance with the general rule in the U.S. Slip op. at 7 and 11. 15 Supreme Court’s decision The University and Small Business Patent Procedures Act of 1980, 35 U.S.C. § 200 et seq., commonly known as the Bayh-Dole Act (the “Act”), allocates rights in a federally-funded “subject invention” between the federal government and the recipient of the research funding. “Subject invention” is defined by the Act as “any invention of the contractor conceived or actually first reduced to practice in the performance of work under a funding agreement.” 35 U.S.C. § 201(e). 16 Supreme Court’s decision The Court noted “the general rule that rights in an invention belong to the inventor,” citing cases dating from 1851 to 1933. Slip op. at 7. While an inventor can of course assign his or her rights in an invention to a third party, “unless there is an agreement to the contrary, an employer does not have rights in an invention.” Id. 17 Supreme Court’s decision The Court discussed a few federal statutes in which Congress “divested inventors of their rights in inventions by providing unambiguously that inventions created pursuant to specified federal contracts become the property of the United States.” Id. at 8 (citing statues related to the Atomic Energy Commission and NASA). The Court then contrasted such statutes with the Act, stating: Such language is notably absent from the Bayh-Dole Act. Nowhere in the Act is title expressly vested in contractors or anyone else; nowhere in the Act are inventors expressly deprived of their interest in federally-funded inventions. Id. 18 Supreme Court’s decision Noting that the Act provides that contractors may “elect to retain title to any subject invention,” 35 U.S.C. § 202(a), the Court next addressed Stanford’s argument that the phrase “invention of the contractor” in the definition of “subject invention” included any inventions of a contractor’s employees. Id. at 9. The Court disagreed, stating that Stanford’s argument “assumes that Congress subtly set aside two centuries of patent law in a statutory definition,” and that it rendered the phrase “of the contractor” superfluous in the definition of “subject invention.” Id. The Court applied the general rule against treating any statutory terms as surplusage. Id. 19 Supreme Court’s decision The Court stated that the Act’s “provision stating the contractors may ‘elect to retain title’ confirms that the Act does not vest title.” Id. at 11 (Court’s emphasis). Relying on dictionaries, the Court asserted that “[y]ou cannot retain something unless you already have it,” and concluded that the Act does not give title to contractors, but rather allows them to retain whatever they may have otherwise acquired. Id. 20 Supreme Court’s decision Turning to § 202(d) of the Act, which allows inventors to retain rights to their invention in some circumstances, the Court stated that section “assumes that the inventor had rights in the subject invention at some point,” id. at 12, and is thus inconsistent with the view that the Act automatically vests rights in the contractor. 21 Supreme Court’s decision The Court observed that the Act does not include provisions for the protection of the rights of inventors in their inventions or of third parties and stated that the absence of such procedures “makes perfect sense if the Act applies only when a federal contractor has already acquired title to an inventor’s interest.” Id. at 13. Finally, the Court noted that its construction of the Act is consistent with the practice of parties subject to its terms. In particular, NIH guidance documents advise that inventors initially own an invention and recommend that contractors obtain assignments from inventors. Id. at 14. 22 Justice Breyer’s dissent Justice Breyer wrote a dissenting opinion questioning the propriety of the Federal Circuit’s ruling that the “hereby does assign” language in Cetus’s agreement was an effective assignment but the “agrees to assign” language in Stanford’s contract was not. The Federal Circuit’s ruling was based on FilmTec Corp. v. Allied-Signal, Inc., 939 F.2d 1568 (Fed. Cir. 1991), which, according to Justice Breyer, “provided no explanation for what seems a significant change in the law.” Slip op. at 7-8 (Breyer, J., dissenting). According to Justice Breyer, where the invention had not yet been conceived, the language of both agreements should have only been effective to confer equitable rights. Id. 23 Justice Sotomayor’s concurrence Justice Sotomayor wrote a brief concurrence agreeing with Justice Breyer’s concerns but finding that affirmance was the correct disposition because Stanford had not challenged the FilmTec rule below. Both Justices Breyer and Sotomayor noted that they believed this issue was open to review in a future case. 24