The Haida - bca-grade-6

advertisement

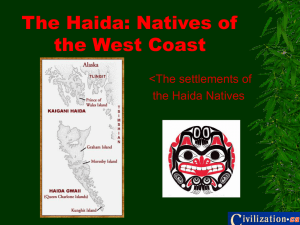

West Coast Native Groups West Coast Native Groups The Haida are part of a larger collection of First Nations peoples who occupy the west coast of British Columbia. Since they are close to each other, they are similar in many ways: 1. They all have permanent homes 2. They all have similar foods 3. They all share similar customs 4. They all built boats to travel on the water 5. They all traded with each other. 6. They often fought against each other The Northwest Coast can be divided up into several main groups, although some estimates put the number of different First Nations groups in British Columbia at 70. West Coast Languages This mountainous area brought about one major difference and that was in languages. Each Native group on the west coast had their own language. Some, like the Haida, had no similarities to any other language. Others had minor similarities. The Northwest Coast people have the most diverse languages of any First Peoples group in Canada. It is estimated that there are nineteen distinct languages spoken by the people. However, if all of the languages are grouped together then they can be divided into five main language groups. The main groups are the Haida, the Tlingit, the Tsimshian, the Nuu-chahnulth (Nootka), and the Salishan. Location: The Haida are located on a small gathering of islands called the Queen Charlotte Islands, which belong to British Columbia. There are two main islands with many smaller islands. The Haida refer to the islands as HAIDA GWAII. Historically, the Haida were located throughout the island. Today, the two largest communities are Skidegate and Masset. A few other Haida communities were located on islands just north of Haida Gwaii which are a part of Alaska, USA today. HAIDA FOOD The west coast of British Columbia is mild for most of the year with plenty of rain. The waters are full of fish and other marine life. The forests are full of vegetation and animals. Because of this, the Natives who lived in this region were ‘hunters and gatherers’. They hunted the animals that lived in the area and collected (gathered) the food that grew plentifully in the area. The people of the Northwest Coast were skilled fishermen and learned to exploit the natural waterways in the area to catch fish. The Pacific Ocean was the main source of food for the people, and, therefore, the men spent a lot of time fishing along the coast. Pacific Salmon was abundant in the waters, and became the most important food resource of the people. In the fall, the salmon would travel up the rivers to spawn, making them easy to catch with nets, harpoons, and traps. They would literally catch thousands of fish in a small area, which was more than enough to feed a family for a year. Haida Food: The ocean also provided them with other fish like the Halibut and smelt. They also caught Crab and other Shellfish like clams, oysters and mussels. Seaweed from the ocean was also a part of their diet. The Haida even caught whales! It was a dangerous process that could take days. It was dangerous because the Haida only had fairly small boats which could be tipped over by an aggressive whale. Once in the water, the Haida fisherman could easily drown or be killed by the whale. On occasion, the Haida caught other sea animals like sea otters, seals and even turtles. The Candlefish The Haida used a lot of fish oil to add flavour to food. The whale and the seal were the most common animal to get oil from. One valuable and important fish to the Haida was the Eulachon (also called candlefish by the Europeans) The Eulachon is a small fish similar to a smelt. During certain times of the year, the Eulachon has a very high percent of oil in its body. This oil can be harvested and used as fuel for lamps. Even when fully dried, the Eulachon will burn like a candle when lit. The Haida travelled to the mainland to trade for this fish and the oil. Native women pressing Eulachon oil Homes: With everything they needed so close to them, the Haida had no need to move from place to place, so their homes were permanent. These permanent homes were very impressive! The Haida lived in rectangular cedar-plank houses with bark roofs. Usually these houses were large (up to 100 feet long) and each one housed several families from the same clan (as many as 50 people.) Perhaps the most famous part of the Haida culture can be seen behind and in front of each home, and that is their totem poles (more later). Haida homes Since it rained a lot along the coast, the trees grew very thick and tall. The huge red cedars were especially important to the people because they could make large houses with them. They cut the trees with stone axes and floated them to their villages. First, a frame was built out of cedar logs. Then, cedar planks were attached to the logs. It was important to overlap the planks to keep the rain out. They used wooden pegs as nails to hold the wood together. They made their houses as huge rectangles, with many posts to hold up the roof and covered them with cedar planks. There were no windows in the longhouses. There was only a hole in the roof to let smoke from the fires out and a single front door to keep the heat in. The longhouses were built with low roofs because they were easier to heat in the winter. Inside a Haida longhouse Inside a longhouse, there was only simple furniture. Each family had bunk beds lined up against the wall for sleeping. Above each bunk, there were storage areas and open shelves. Below the bottom bunks, they dug holes (around two feet deep) to store and cool food. Each family would also have their own small fire pit for cooking. Woven cedar mats were hung from the ceiling to separate the different family areas. The chief had the biggest area and the most private area which would be separated by a wooden wall. When one family member got married, a new section of the longhouse would be sub-divided for the new family. When the Haida house got too full, a new one would be built and some of the families would move into it. Screened off area for the chief Haida villages Houses were always grouped together forming small villages. Some villages had as many as 1,000 people, all living in only 30 houses! Each village was marked by totem poles. All the houses in a village were lined up sideby-side facing the same direction- towards the water. House fronts were commonly painted as were the totem poles, which were carved with the family crest. (we’ll learn more about totem poles later on) If an individual built a longhouse for his family, then he lived there with his wife and children, and then their children. When the children got older, they were assigned (by the head of the family) a new space inside the longhouse. On the other hand, if the village built the longhouse together, then it would be the Chief's responsibility to assign living spaces to each family. When the owner of a longhouse died, the family gave the longhouse away or burnt it to the ground. It was believed that if the family stayed after the death, then the spirit of the dead person would worry too much about the family. Haida Clothing: Haida men wore a breech cloth and long cloaks. A breechcloth is a long rectangular piece of tanned deerskin, cloth, or animal fur. It is worn between the legs and tucked over a belt so that the flaps fall down in front and behind. Sometimes it is also called a loincloth. Women wore knee-length skirts and poncho-like capes. Haida clothing was usually woven out of fiber made from cedar bark, but some garments were made of deerskin and otter fur. In cold weather, Haida people wore moccasins and heavy caribou robes, but most of the time, they preferred to go barefoot. For formal occasions, Haida people wore more elaborate outfits, with tunics, leggings and cloaks painted with tribal designs. Some important and wealthy Haidas wore the spectacular Chilkat blankets, which were woven from cedar bark and mountain goat hair. Haida Clothing Pictures The Haida Canoe The Haida tribe was wellknown for their large dugout canoes, which they made by hollowing out cedar logs. A Haida canoe could be more than sixty feet long and was built to withstand stormy waves and could carry 10 000 pounds of cargo (like fish). Even other Northwest Coast Indian tribes, who all made impressive canoes themselves, admired the canoes of the Haida carvers. The Haida tribe used these canoes to travel up and down the sea coast for trading, fishing and hunting, and war. Modern Canoes The tradition of large quality canoes continues today. Modern Haida carvers still spend hundreds of hours hollowing out cedar logs and carving and painting highly detailed and highly prized canoes. The art of making the Haida canoes was almost lost by the beginning of the 1900s. It may have been lost completely if not for the work of one man named Bill Reid. Bill Reid was born in Victoria BC and was half Haida, but his Haida mother kept this from him. When he did find out, he explored his culture and learned that it had almost disappeared. Over time, he became an expert in Haida art, especially canoe building. He decided to become a canoe builder using traditional Haida techniques. His most famous canoe was the 15-metre war canoe Lootaas (Wave Eater), which was carved from a single cedar tree from Haida Gwaii. Bill Reid was asked to build this canoe for Expo ’86, the world’s fair held in Vancouver. The massive canoe was the first of its kind carved in the 20th century and ‘wowed’ Expo ‘86 spectators. It triggered a rebirth in canoe building across the province of British Columbia, as well as the re-emergence of traditional tribal canoe journeys and festivals among first nations peoples. Bill Reid’s canoe The Lootaas canoe enjoyed a rich legacy. It was paddled all the way from the Haida Gawii islands to Alaska, and it even made an honorary journey up the Seine River in France to be displayed in Paris’ Museum of Man. When Bill Reid died in 1998 at age 78, the canoe was used to transport his ashes back to his adopted home on Haida Gwaii. An exact replica was made for the Museum of Natural History located in Ottawa. Haida Society The Northwest Coast people never developed a democracy government. Instead, their society was ruled by wealth. The wealthiest clan had the most power. Their society included different classes: nobles, commoners, and slaves (acquired through War or purchase). The Haida were divided into basic social units. In the family groups, the oldest and highest ranking person was named the Chief of the family. Then within each family, a person's rank was determined by their relationship with the Chief. For example, if the chief was your father, you had great social standing. If the chief was a cousin, you would have a lower social rank. Chiefs were responsible for distributing wealth among the people. Those who had a higher social status received more, all the way down to the lowest ranked individual. Groups of families lived together, forming villages. Within each village, each family was ranked. The Chief of the most powerful family became the Chief of the village. The village Chief displayed his family's crest on the village totem poles. The Haida were divided into two or more family 'clans‘: the Raven and the Eagle clans. Clan membership was always passed down through the mother's side of the family. So if your mother belonged to the Raven clan, then her children belonged to the Raven clan. Each person always married someone from the other clan. One thing that set the Haida people (and other West Coast Native Groups) apart from other First Nations people groups in Canada was how they recognized ownership of land and property. Haida families claimed good spots for fishing or hunting or gathering food. The amount of property that a family claimed (owned) contributed to their wealth within their community. Haida Totem Poles Although the Haida had been making totem poles for hundreds and hundreds of years, most experts believe these early totem poles were much smaller and far less common. It was not until after first contact with the Europeans that the totem poles became very large and very common. They reached their peak between 1850 and 1880. The Haida gained wealth through trading furs with the Europeans. Through trading, the Haida acquired axes, knives and carving equipment. Having more wealth and better equipment allowed the Haida to built more and greater totem poles. Totem poles represented family history and told the story of the people that lived in the houses. The Haida did not believe that the poles had any religious meaning at all. Chiefs competed with other chiefs in the village to see who could have taller and more detailed totem poles. Carvers were in great demand to create these rich works of art. There are different types of totem poles, each with a different function: Totem Poles Perhaps the greatest and most well known part of the Haida culture is the Totem pole. The totem pole is a massive cedar tree cut down and hand carved by a single person or a group of people. To us, most totem poles look the same. But to the Haida, there were many kinds of totem poles each with their own important purpose. House poles were carved with symbols of family history and were positioned at the back of the house for all to see. These poles had a second purpose since they were a part of the house construction and were used to support the main beams of the building. House poles could also be located beside the house or be free-standing. Some longhouses featured a tall house frontal pole which would be located at the main entrance of the house. People entered the house through a hole located at the bottom of the house totem pole. Mortuary poles were used for high-ranking individuals or chiefs. These poles had large holes cut out of the upper portion and carved with crests of the dead person. The deceased body is placed into a painted box and remained in a mortuary house for a period of one year. The remains were then moved to a smaller box and placed into the hole of the pole. The front opening was covered with cedar boards and then painted or carved to complete the original design. Mortuary poles Memorial Pole of Chief Kalilix. Shame Totem Pole Memorial poles stood on their own apart from the village. Each pole was a single tribute to a great chief and showed the many achievements of the deceased chief. The pole was raised one year after his death. The last kind of totem pole is the “Shame” pole. This pole was seldom used by any First Nations groups, including the Haida. A shame pole was built when a native group or even an individual did not repay a debt. The pole was built in public so everyone could see that a debt had not been paid. It was meant to embarrass the individual or group into repaying the debt. When the debt was paid, the pole was removed. Many shame poles remain unidentified today because the original debt, now long forgotten, was never repaid. Shame poles The Watchmen A totem pole is to be read from the top down. The character on top is not necessarily high ranking. The largest figure would be the one that is featured in the story. The smaller figures are sometimes fillers and have some function in the story. The "Watchmen" can be identified as three carved men wearing tall hats sitting at the top of tall totem poles, which are attached to the chief’s house. The main function of the watchmen was to warn the chief and the villagers of danger. The middle watcher faced the ocean to search for incoming canoes from other villages, and the other two looked to the sides and kept watch over the village. Totem poles don’t last too long on the Pacific coast of Canada. The heavy rain and humid climate means the cedar wood of the totem poles rots and decays quickly. There are virtually no totem poles remaining from the early part of the 1800s. They have all rotted away. Even the totem poles remaining in Haida Gwaii today that were carved in the late 1880s or 1890s show extensive decay and many of the carved and painted faces are difficult to see. Although many of the very large totem poles still remain in Haida Gwaii today, rotting where they were originally placed, others have been removed and have been relocated in museums around the world. In these environmentally protected museums, the Haida totem poles do not rot, and will remain for many hundreds of years for all to see and appreciate. The Potlatch 'Potlatch' was the name given to most Northwest Coast First Nations celebrations. It comes from a First Nations word 'pachitle' meaning 'to give'. A potlatch was a big celebration that often took more than a year to plan. The ceremony usually happened when a person had a change in social status, for example, marriage, birth, death, and coming of age, or when a person became a chief. It included a feast, singing and costumed dancers, and some potlatches lasted as long as two to three weeks. Potlatch Most importantly, though, potlatches became a way in which wealthy families could show off their wealth to others. Each person invited to a Potlatch received gifts related to their social rank. Some examples of gifts would be canoes or slaves for high social class people, carved dishes and eulachon oil for those of slightly lower social class. In the Haida culture, wealth was not shown by how much you could gather, but by how much you could give away. The more wealth that a family gave away as gifts during the potlatch, the more respect and honour was shown to them by the community. Dignity Potlatch Another type of potlatch was called a dignity Potlatch. This type of potlatch was much smaller and didn’t take very long to plan. A dignity potlatch took place when a member of the high social class, like the chief, did something that caused him great embarrassment. This could be falling out a tree or falling out of his canoe or failing to catch food. In the Haida culture, a person could not be laughed at. If they did get laughed at they lost all dignity (respect) from the people. Therefore, a dignity potlatch allowed an important person to get back some of their dignity…for a price! Shaman Haida Religion In Haida culture, their customs, beliefs and history were passed down orally through stories, songs, and dances. They had stories about why certain things occurred, for example, the changes in season. There were also stories about creation and how they first appeared in this world. All of these stories were passed down to the next generations. The Haida believed that they were surrounded, at all times, by supernatural beings interfering with the natural or the everyday world. In their culture, spirits were connected to all living things. The only link between the spirit world and the natural world was the 'Shamans' or 'Medicine Men'. Shaman equipment Shamans It was a Shaman's job to cure the sick, to ensure that there was enough food, and to influence the weather. The belief was that they had the power to do all those things through an ability to communicate with the spirit world. Both men and women could have been Shamans, however, they were most often men. A Shaman would wear bear skin robes, aprons, rattles, skin drums, charms, necklaces and sometimes masks. When someone was sick, it was believed to be caused by the spirit world. Shamans were the only people who could communicate directly with the spirits, so they were the only ones who could cure the sick. How sad that the Haida did not believe that a personal relationship with God was possible and that they needed special men to speak for them. God desires to hear from all of us and He alone can answer all of our prayers. Through Christ, we can talk to God individually. We don’t need someone to do it for us. Haida Art Art played a major part in Haida culture. They were known for their: Basketry (basket, hats) Woodworking (masks, totem poles) Weaving (Chilkat blankets) Baskets: The Haida people used baskets for storage and trade. This Haida cedar bark basket at the top of the pictures would have been used to collect clams. Others were used to collect berries and other food. Baskets were often very artistic and colourful as well as being very functional. Haida Hats Hats were particularly important for the Haida people because they were used as protection from the rain. Getting a hat was much more difficult for the Haida than for us to get a hat. Hats had to be ordered individually from the hat maker. Hats were woven on a stand with a wooden form appropriate to the head shape and size of the person buying it. Male artists painted the hats with the symbols of the family. The colours of paint were limited to red and black (with blue or green sometimes). In early historic times, Haida women also sold their hats to Europeans and Americans who were trading or travelling in Haida territory. Painted woven hats became a popular European tourist item late in the nineteenth century. Transformation mask Haida Masks When it came to wood, the Haida were very talented artists. We have already looked at totem poles and the canoes, yet the Haida were also very good at carving masks. Haida carved masks were an important part of all of their ceremonies. One of their very special masks was called a transformation mask. It was a carved wooden mask that could open in the middle to reveal another carved wooden mask of a different face. This mask allowed the dancer to become multiple characters. More Haida Masks Another type of mask used in ceremonies was made of copper. It was quite rare since the Haida did not often use metal. Having this mask was a sign of great wealth in the Haida culture. Bentwood boxes: The Haida made bentwood boxes from a single cedar plank. The plank was steamed and then bent at three corners to form a box shape and then pegged together. Then a top and bottom were added. Bentwood boxes were used to serve and store food, and they were also common at ceremonial feasts. They were a common gift to be given away at potlatches. Copper Mask Bentwood boxes Directions on how to build a bentwood box. European Influences In 1774, the way of life for the remote Haida people drastically changed when the first European explorer, Juan Perez from Spain, discovered the Queen Charlotte Islands. He never landed on the islands, but a few of the Haida canoed over to his ship and traded with him. Perez was low on food, so he couldn’t stay long. He quickly left the area and headed further south. Captain James Cook also saw the islands in 1774. In 1787, another British explorer named Captain George Dixon named the islands after his ship, the Queen Charlotte. Sea otter The Fall of the Haida The islands were of little interest to anyone until Europeans discovered the sea otter. The fur of the sea otter was prized throughout Europe and Asia. Soon, hundreds of Europeans were eager to trade with the Haida. The contact with Europeans increased Haida wealth, but many ‘White man’ diseases were devastating to the Haida who had no immunity. Thousands died of tuberculosis and smallpox. Within a few decades, the population of the Haida fell from 7 000 to fewer than 700. Those that remained gathered to form two small villages. Government agents and missionaries came to the area to bring the Gospel, but also ‘western’ ideas. The Canadian government believed the Haida needed to become more ‘Canadian’. Haida Gwaii Cultural Centre The Haida Today Through the work of Bill Reid (we already learned about him) and other Haida people, the Haida culture has had a rebirth over the past 30 years. Today, world wide tourism to Haida Gwaii helps keep this culture alive. The Haida Heritage Centre at Kaay Lliagaay is an award-winning Aboriginal cultural tourism attraction located on the islands. The centre houses the Haida Gwaii Museum, additional temporary exhibition space, two classrooms, the Performance House, Canoe House, Bill Reid Teaching Centre, and The Carving House. The Haida are also battling the BC and Canadian governments concerning logging on their island and other parts of British Columbia. Haida traditional ceremony tourism Hopefully, the future will be strong and prosperous for the Haida people and their culture. The more we learn about it and appreciate it, the better chance they have of surviving.