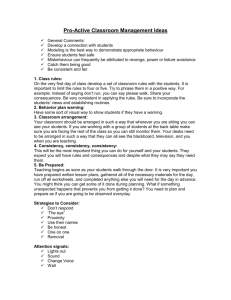

Persuasion_Principles_Commitment,_Consistency

advertisement

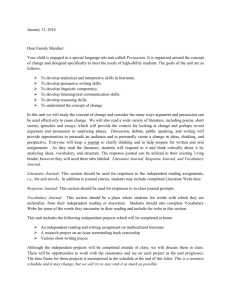

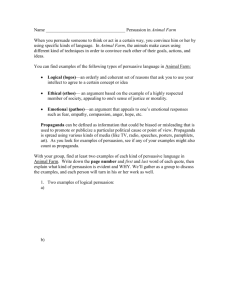

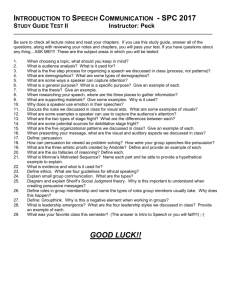

The Science of Persuasion Using Persuasion Principles & Techniques in Food Security, Child Survival and other Community Development Programs PART 1: Commitment & Consistency This media product is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Food for the Hungry and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Tom Davis, MPH TOPS Senior Specialist for Social & Behavioral Change FH Chief Program Officer April 6, 2011 Starting Point: Our Niche We (PVOs/NGOs) will not develop the next great vaccine or medicine. We may (and should) develop and discover the best community mobilization and behavior change approaches. We can innovate and test them. Need to know the literature, “what works in the lab” Some replication of these studies in developing countries The Science of Persuasion Principles from decades of social psychology research Used by community organizers, advertisers, social marketers, politicians, and those promoting health behavior change. Influence: the Psychology of Persuasion, The Human Connection, and Fostering Sustainable Behavior Data from careful observation and experimentation A relatively young discipline The Science of Persuasion Persuasion about: literature answers questions • kinds of messages that are most memorable and persuasive • what techniques / actions make people more likely to respond positively to a request • how we are influenced / how we influence others • how we decide “who we are” (identity) and what we should do • how and when we look to others to know what to do • the effectiveness of incentives Some applicable to our work When do we persuade? What are the things that we try to persuade people to do in our programs? Household-level and on-farm behavior change Community-level mobilization and change Service (e.g., health, financial) utilization Making “sub-commitments” like agreeing to attend a meeting. What doesn’t work well in behavior change… See Change or Die (Alan Deutschman) What doesn’t work very well in terms of achieving behavior change: › Facts › Fear › Force Info Only What works in promoting behavior change: › Developing a relationship with someone you trust who gives you hope for change. › Learning and practicing skills › Changing our worldview or “reframing.” › Focusing on determinants of the behavior. Care Group Performance: Perc. Reduction in Child Death Rate (0-59m) in Thirteen CSHGP Care Group Projects in Eight Countries (Green line = average of USAID child survival programs) AR C/ Ca m bo W di a R/ V W ur R/ I V FH W u /M R/V r II oz ur ( W Be IV R/ l Ca l agi m o) W bod R/ ia W Ma R/ la w M W ala i R/ w Rw i II Cu a ra nd a m . / G P SA la n ua W /K t SO en /Z ya am Av M b g. Ca TI/L i a re i be ri a G r Av p P g CS roj . Pr oj . % Red. U5MR 60% 48% 50% 41% 42% 34% 40% 33% 33% 32% 30% 29% 28% 26% 30% 23% 14% 14% 20% 12% 10% 0% CSHGP Project Series1 The effectiveness of “block leaders” Nine Care Groups vs. Average of 58 CSHGP Projects, RapidCATCH Indic. Gap Closure 100% 85% 77% 80% 68% 58% 53% 46% 40% 42% 33% 27% 25% 20% 20% 11% 12% 0% -8% Un d Bi erw rt h t Sp ac SB A TT 2 Co EB F m pF ee Al d lV a M cs ea sle s Da ng ITN er Si gn In cF s AI luid DS s Kn ow HW W Al S lR ap id % better 60% -20% RapidCATCH Indicator RapidCatch Indicator So persuasion is a part of behavior change... Before you can maintain a behavior, you have to: › Be persuaded to come hear about it › Be persuaded to try it out once › Be persuaded to give it a chance or try something a bit more intensive. Seven Principles of Persuasion The principle of… 1. Commitment & Consistency 2. Social Proof 3. Reciprocation 4. Contrast 5. Liking 6. Authority 7. Scarcity. We will focus on the first one. Note: All can be used for both good and evil! Application Across Cultures Cialdini: Human Universals, but strength will vary across cultures. In collectivistic cultures/people: Relationallybased principles (e.g., Social Proof, Liking) are sometimes stronger than individually-based principles (e.g.., commitment/ consistency, authority). But all still apply. Principle #1: Commitment & Consistency Prominent Theorists: Festinger, Hieder, Newcomb Once we have made a choice, taken a stand, or made a verbal commitment, we are more likely to do things to be consistent with that choice. Personal (internal) and interpersonal (external) pressure to behave consistently “…[O]ur nearly obsessive desire to be (and to appear) consistent with what we have already done.” (Cialdini) Principle #1: Commitment & Consistency We have solid “hardwiring” for living consistently “Our best evidence of WHO WE ARE comes less from our thoughts about ourselves, but from what we “see ourselves doing” … and also what we “hear ourselves saying.” Commitment & Consistency: Some of the evidence Thomas Moriarty study: Staged “thefts” on NYC beach: How many people intervene to stop the theft? 20% Same set up, but accomplice asks person to “watch my things” during their walk. How many people intervene? 95% Why would they do this? Why take the risk? We highly value Consistency Moriarty, T. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Vol 31(2), Feb 1975, 370-376. Commitment & Consistency: The evidence Steven J. Sherman’s study on door-to-door donation collections. (Call it “self-prediction then request”) Group #1: Telephoned residents for survey: Predict what you would say if asked to spend three hours collecting money for the ACS. Then ACS representative calls and asks them to spend three hours collecting money for the ACS. Group #2: Just call them once and ask them to volunteer three hours. What difference would you expect in volunteer rate? Seven times more people volunteered in Group #1. Why? We value Consistency. Repeated many times in different settings and with different issues. Sherman, SJ. On the self-erasing nature of errors of prediction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 39 (1980): 211-21. Commitment & Consistency: The evidence: A darker example… Chinese efforts to convert American POWs to communist point of view. How? “Start small and build” POWs first asked to make mildly anti-American statements. Then asked for more substantive requests: “List ways that US is not perfect” Next week: “Read your list in a group” Next week: “Write an essay and discuss these in greater detail” Next week: The essay is broadcasted on the radio. Commitment & Consistency: The evidence “Suddenly, the person finds himself as a “collaborator” … and knowing that he wrote and said what he did without any strong threats or coercion, many a man changed his image of himself to be consistent with the deed, often resulting in even more extensive acts of collaboration.” Commitment & Energy Conservation Michael Pallak (1980): “Low-balling”: Giving someone an initial inducement to do something then removing the incentive once the person discovers other reasons to do it. 1. Start of Iowa winter, residents who used natural gas contacted. 2. Sample #1: Given energy-conservation tips and ask them to conserve fuel in the future. 3. All agree to try – but no savings seen (from utility bills) as compared to control neighbors. 4. Good intentions + info = No change. Commitment & Energy Conservation 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Sample #2: Given energy-conservation tips and asked to conserve. Told that those who agree to save would have their names publicized in the paper as publicspirited, fuel-conserving citizens. Result: Savings of 422 cubic feet of natural gas as compared to controls (about 12.2% savings, ~$6.58/HH in DC). Next they send a letter: Sorry, can’t publish your names in the paper. Result: Families conserved even more fuel than they had earlier (15.5%, ss). Commitment & Energy Conservation 1. 2. Possible Reasons: New energy habits, began feeling good about their publicspirited efforts, began appreciating lower bill, proud of their capacity for self-denial, began viewing themselves as “conservation minded.” Why pulling the incentive worked: By pulling the newspaper incentive, people had to “fully own” their commitment to conservation. Replicable: Repeated study in summer w/AC. W/promise of newspaper publicity, 28% decrease in electricity (as compared to controls). After removing newspaper offer, energy savings increased to 42%. Ethical?? Probably need to say it is a possible but not certain benefit. Or only use incentive once… Commitment & Consistency: The evidence Proctor and Gamble’s Testimonial contests (1940): “Why I like ivory soap…” in 50 words or less. Win a CAR. Result #1: Tremendous number of people writing out why they like the product … Result #2: Hundreds of thousands more people liking the product more (“watching what you’re doing”) “The Next Ivory Family” Commitment & Consistency: The Evidence “Foot in the door” technique (Freedman & Fraser) EX: Group #1, Researcher asks homeowners if they can put a big, ugly public-service billboard on their lawn … a “big ask”. Only 17% agreed. Group 2: Volunteer comes to the door and asks them to display a 3” square sign that says BE A SAFE DRIVER (“small ask”). (Almost all agreed.) Several weeks later, they are asked to post the big, ugly sign (the “Big Ask”) Not this bad … but close… Commitment & Consistency: The Evidence Result you would predict? 76% agree to it! Another example: Researchers ask people to sign a petition to “keep California beautiful”. Nearly all agreed. Then asked people to post big ugly sign about driver safety (different issue): Almost half agreed to it (vs. 17%)! Why? Self-image changes. Another foot-in-the-door study.. Small request: Researcher calls and asks about household product use. If they agree, they answer 8 questions about soap use. Big request was for 5-6 men to come and inventory all the household products in your house. Researcher makes a single contact with the big request: 22.2% compliance Researcher just familiarizes the person with the subject on first call and then makes the bigger request on the second call: 27.8% compliance Researcher makes the small request (but doesn't ask the person to do it) and then calls back with a bigger request: 33.3% compliance Researchers makes a small request which was done then makes a bigger request: 53% compliance Freedman, J. L., & Fraser, S. C., Compliance Without Pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique, JPSP, 1966, 4, 196202 Other examples & tips American Heart Association donations study: “You are a generous person” (“positive labeling”) vs. Thanking What do you predict? Who gives more? How much? Generously-labeled people gave 75% more. Asking people to ask others to make a commitment after they themselves make a commitment increases total commitments and sustainability of the behavior. “Those who were asked to speak to their neighbors (to “grass cycle”) increased their own grass cycling, but also that of their neighbors… findings were still observable twelve months later (cf: Care Groups). (McKenzie-Mohr) Other examples & tips Just ending a blood drive call with, “We’ll count on seeing you then, okay?” increased attendance from 62% to 81%. (Lipsitz et al, 1989). [Looking for a verbal commitment.] Individuals asked to wear a lapel pin (“identifier”) publicizing Canadian Cancer Society twice as likely to donate subsequently. (Pliner et al, 1974) Tips: Group commitments can be effective when there is good group cohesion. Commitment can be increased by actively involving the person in an activity/action. Consider asking for commitments when a service or product is provided Only ask for a commitment when the person shows an interest in the behavior/activity. Quick review of persuasion methods mentioned: Self-prediction then request technique Start small and build Low-balling Testimonial/essay Foot-in-the-door Positive labeling “Give a commitment, get a commitment” Identifiers Summary of techniques related to Commitment & Consistency principle… Essays and speech contests “Start small and build” idea. Asking for small, verbal or written commitments. Asking people what they would do before asking them to do it – use local surveys Local petitions. Posting/wearing identifiers of support/commitments. “Foot in the door” technique (small ask then large ask). Low-balling (offering incentives to get someone to try something and then removing the incentive). Self-prediction then request technique Positive labeling (“you’re generous”) “Give a commitment, get a commitment” Commitment & Consistency: Some ideas on how to use it Use essay and speech contests, with widespread participation. Essays and speeches do not have to be completely “on message.” Use “start small and build.” Ask those who are ambivalent to list one thing that they do like about a behavior (e.g., planting in rows) or what they don’t like about their current behavior. (What are these questions called in the MI literature??) Then ask them to list them. Etc… Related: Use more simulations where people rehearse behaviors (e.g., talking to your husband about planting a home garden). Commitment & Consistency: Some ideas on how to use it Ask for small, verbal or written commitments, but without any pressure. Ask people what they would do before asking them to do it – use local surveys about future action. (“How likely would you be to participate in a community campaign to…”). Use local petitions. (“Do you agree that our community needs to …? If so, please sign here.) Use “foot in the door”: Ask for small commitments before asking for big commitments. Stage your curricula and interventions accordingly. More Resources: Application Examples You can download a table with a summary of this principle, the techniques associated with it, and ideas on how to use them by using this link (there are underscores _ between each word in the title): www.caregroupinfo.org/docs/Application_ of_Persuasion_Principles.doc Further Reading Influence: Science and Practice (4th ed.) or Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion (Robert Cialdini). Translated into Spanish, French, Portuguese, Thai, Indonesian, Arabic, and 20 other languages. (See Amazon for language group) Fostering Sustainable Behavior (C-b social marketing, Doug McKenzie-Mohr and William Smith) Switch & Made to Stick (Chip & Dan Heath) Change or Die (BC in general, Alan Deutschman) How We Decide (Jonah Lehrer) The Human Connection (get from Tom, tdavis@fh.org) Marketing Social Change (Alan Andreasen) Persuasion: Theory & research (2nd Ed.). O‘Keefe, Daniel J. (2002). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.